Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Atika Farzana Urmi* and KC Bhuyan

Received: October 24, 2018; Published: November 08, 2018

*Corresponding author: Atika Farzana Urmi, Department of Mathematics, American International University, Bangladesh

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2018.10.002017

The present analysis was based on data regarding level of obesity of 662 children and adolescents of 560 families of students of American International University-Bangladesh. The children and adolescents were classified by level of obesity, where level of obesity were measured by percentiles of BMI. It was observed that, among 662 children and youth 465 were in underweight group. Obesity and severe obesity were observed among 9.1 percent children and adolescents. Among the obese and severely obese group, 53.% killed their time by watching television and another 26.7% spent their time by doing other works including games and sports. Obesity and severe obesity were associated with time spent by the children and adolescents. Among these groups 31.7% were suffering from diabetes. Diabetes and level of obesity were significantly associated.

Among obese and severe obese group, around 42% were habituated in taking restaurant food and these two characters are also significantly associated. Some socioeconomic factors of parents are also associated with level of obesity. Pearson’s Contingency Coefficient ( C= 0.281 ) showed that the degree of association between obesity and fathers’ occupation was higher followed by the degree of association with father’s education and family income. Factor analysis was done to identify the most important factors for the variation in the data set under study. It was seen that fathers’ education was the most important variable for the variation in obesity levels followed by mothers’ education and fathers’ occupation.

During the past 3 decades, prevalence rates of childhood and adolescence obesity, measured by body mass index (BMI) above the 95th percentile for age and sex, are in increasing trend. The problem of obesity is one of the most important public health issues [WHO 2002]. Again, excess body weight is the sixth most important risk factor contributing to the overall burden of disease worldwide. Around 110 million children are now classified as overweight or obese [1]. Approximately, 43 million pre-school aged children throughout the world have been estimated to be overweight [2] and 92 million are considered to be at risk of overweight. In Bangladesh, overweight and obesity are in increasing trend and prevalence of these range from 1% to 17.9% with higher percentage among urban children across different age groups and sexes [3]. The increasing prevalence of overweight and obesity among children (0-12years) and adolescents (13-19 years) has emerged as a major public health threat in Bangladesh [4]. Obesity is associated with significant health problem in the pediatric age group and is an important early risk factor for much of adult morbidity and mortality [5].

The problems of obesity among children and youth are manifold. Some of these are

a. Health problem,

b. Insulin sensitivity,

c. Abdominal abnormality,

d. Epidemiology,

e. Environmental risk,

f. Social change,

g. Cardiovascular abnormalities,

h. Psychological abnormalities etc.

Obesity is associated with significant health problem in the pediatric age group and is an important early risk factor for much of adult morbidity and mortality [6-9]. Childhood obesity frequently persists into adulthood and upto 80% of the obese children reported to become obese adults [10]. Many of the metabolic and cardiovascular complications of obesity are already present during childhood and are closely related to the presence of insulin resistance, the most common abnormality of obesity [11]. In some study [12,13] it was mentioned that insulin resistance might be a result of the imbalance of fat distribution in both the abdominal fat depot and skeletal muscle tissue of youth. The most common medical morbidities associated with obesity include metabolic risk factors for type II diabetes including high blood pressure, high cholesterol, impaired glucose tolerance and metabolic syndrome [14,15]. Behavioral factors have significant effects on metabolic risk. It had been observed in some research findings that youth who do not meet guidelines for dietary behavior, physical activity and sedentary behavior have greater insulin resistance than those who do meet guidelines [16].

Psychological abnormalities are closely associated with obesity in children and youth. Obesity in youth may be associated with later depression in childhood [17]. In addition, abdominal obesity seems to be strongly associated with concomitant depression in males. Female obese as adolescents may be at increased risk for development of depression or anxiety disorders. Environmental risk factors for overweight and obesity are very strong and interrelated. Sub optimal cognitive stimulation at home and poor socioeconomic status predict development of obesity [18]. Parental food choice significantly modify child food preferences [19]. Children and adolescents of poor socio-economic status tends to consume less quantities of fruits and vegetables and to have a higher intake of total and saturated fat [20,21].

Early rebound of BMI is linked to glucose intolerance and diabetes in adults [22]. Short sleep duration in children is also associated with an increase in the odds of becoming obese as well an increase in body fat percent [23]. The childhood obesity has significant impact on dramatic and rapid changes in the society. It is evident that individual’s eating and physical activity behaviors are heavily influenced by surrounding social and physical environment contexts both for adults and children [24]. Urbanization related intake behaviors that have shown to promote obesity include frequent consumption of meals at fast food shop [25,26] which is, in most cases, high calorie food containing high level of fat and low level of fiber. The intake of sweetened beverage from fast food shops also promotes obesity [24].

The behavior of food intake are cultivated in an environment in which high calorie food is abundant, affordable to children of affluent families, available and easy to consume with minimal preparation as is the case of urban cities throughout the country. Low level of physical activity is definitely promoted by an automated and automobile-oriented environment that is conductive to a sedentary lifestyle [27]. The level of obesity may increase in the urban area if there is no scope of safe walkways, playgrounds and other avenues for physical activity related recreation [24]. From the above discussion, it can be concluded that growing obesity among children and youth is of great concern throughout the world. Many of the complications are silent and often go undiagnosed. The obese children are at high risk for the development of early morbidity. Considering all these aspects discussed above, the objective of the study was planned to identify the socio-economic factors which were more responsible for the variation in the level of obesity among children and adolescents under 18 years of age coming out from affluent families. The specific objectives were:

a. To identify the factors associated with overweight and obesity of children and youth and to test the significance of association of social factors with level of obesity and overweight. Also, to measure the degree of association.

b. To identify the most important factors for the variation in the data set of levels of BMI and social factors of families.

The present analysis was based on 662 responses observed from 560 randomly selected affluent [28, 29] families of students of American International University - Bangladesh during Summer 2016-17 semester. During the semester there were 9488 students in the university. One of our objectives was to estimate the proportions of children and youth of different levels of obesity along with a combined proportion of obese and severe obese group of all ages of children and youth. In a previous study [4] it was reported that there were 7% overweight and obese children and youth in Bangladesh. Accordingly, we had decided to have a proportion of at least 7% overweight and obese children and youth with margin of error of 2% with 95% confidence in our study

To have such an estimate it required a sample of students of size n, where n=(z^2 pq)/d^2 = 625 [ proportion of expected obese and overweight children and youth, p = 0.07, q =0.93, margin of error, d =0.02, normal ordinate for 95% confidence, z= 1.96].

This sample size covered 6.6% students of the university. The sample students were selected by simple random sampling method and were expecting at least responses from 5% families of the students. However, information were received from 560 families , covering the data of 662 children. The data were collected through pre-designed and pre-tested printed questionnaire covering the questions related to the demographic characteristics of the children and youth of age below 18 years and the questions related to the socioeconomic variables of the parents. The randomly selected students were given written instructions how to collect information and they were requested to help in collecting information from their parents, who were very much concerned about the health hazard of their offspring. The children’s fathers / mothers filled in the questionnaires as they were under 18 years of age and some were even below 10 years. The important collected information were age, height, weight, sex, food habit, time spent, involvement in co-curricular activities, if it is feasible, of the children.

To study the socioeconomic background of the children the information regarding parent’s level of education, occupation and income were also collected. For youth having diabetes, the latest blood sugar level measured by registered practitioner or measured in a registered clinic also recorded. Association of level of obesity of offspring with families’ socioeconomic back ground were examined using chi-square test, where significant association was concluded when p-value ≤0.05. Factor analysis was performed to identify the most important factors responsible for variation in the data set collected from the children and adolescents. For factor analysis the variables used were residence of respondents, their age, value of BMI, utilization of time, prevalence of diabetes among them, parents’ education, occupation and income. Some of the variables were qualitative in character. These variables were transformed to nominal measures by assigning numbers.

The data of the present analysis included different social, medical and economic aspects of 662 children aged 18 years or below of 560 randomly selected families of students of American International University- Bangladesh. Amongst the studied children 58.2% were males and 41.8% were females. The children and youth were classified by their gender and level of obesity. The level of obesity was decided by the level body mass index (BMIkg / m2). As methods of direct determination of body fat is difficult, the diagnosis of obesity is often based on body mass index [BMI]. Among children aged 2-19 years the obesity is measured by BMI< 5-th percentile=underweight, BMI is between 85th to 95th percentile=overweight, BMI >95th percentile is obese and BMI is 120% of 95th percentile = severe obesity [30]. For all the children and youth, the mean BMI was 17.67 with a standard deviation 10.58. The underweight group of children and adolescents had BMI < 23kg/ m2. The BMI for other 3 groups were 23 -< 30, 30 -< 45 and 45+. The BMI values were decided according to the percentile’s values . The classified results are shown in Table 1. Obese and severe group of children and adolescents were 9.1 % . This finding is almost similar to that observed in another study [4]. It was seen that among the male children 77.4 percent were underweight. The corresponding figure among females is 60.3 percent.

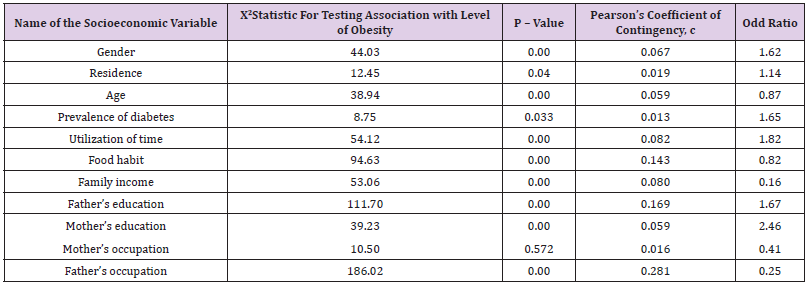

The differential in obesity by gender were significant [χ2= 44.03, p-value= 0.00]. The information of 72.5% children were reported from urban area. The corresponding percentages of rural and semi-urban children were 18 and 9.5 , respectively. The classified information of number of children of different levels of obesity belonging to different residential areas were presented in Table 2. It was seen that maximum village children ( 76.5%) were underweight compared to urban and semi-urban children. Again, among the village children, number of obese and severe obese groups were lower compared to other groups of children. The differences in proportions of level of obesity and residence of children were significantly different [χ2= 12.45, p-value= 0.04] The investigated children and youths were classified into three classes by their age levels. These three groups of children were again classified by their level of obesity. The classified results were shown in Table 3. It was seen that 72.5% children and youths of age group 10 years and above were underweight. The proportions of underweight children of other two groups were lesser than the percentages of overall underweight group of children. The higher percentage of overweight group was observed among the children of age less than 5 years. This differential in proportions of level of obesity according to age groups was highly significant as calculated χ2= 38.94 with p-value = 0.00. Amongst the investigated children and youth 22.8% were diabetic (Table 4).

The corresponding percentage among obese and severe obese group together was 31.7%. Diabetes was less prevalent among overweight group (16.8%). The differences in proportions of diabetic group among children with different levels of obesity were significant [χ2= 8.75 with p-value = 0.033]. The present study group of children were mostly living in city center (72.5%) and they had enough scope to be involved in physical activity like games and sports. Still majority of the children (39.9%) spent their time by watching television and 16.8% slept after or before their academic activities. One-fourth (26.4%) of the investigated children mentioned that they were involved in some other activities including games and sports [Table 5]. Around 72% of severe obese group killed their time by watching television. The corresponding percentage among obese group was 45.2%. The differences in proportions of utilization of time by the children of different obese groups were significantly different as [χ2= 54.12 with p-value = 0.00]. Let us now observe the food habits of investigated children and adolescent. As the investigating units were mostly from affluent residents of city, they had the scope to get sufficient foods, with proper hygienic measures. Among the investigating units 47.9% (Table 6) were habituated in taking food from restaurants. Among the obese children 54.7% were habituated in taking restaurant food. Of course, higher proportions of underweight (46.9%) and overweight group of children (53.3%) were habituated in taking restaurant food. However, the differentials in proportions of children taking restaurant food according to different levels of obesity were significant [χ2= 94.63 with p-value = 0.00]. Usually the children of affluent families were more prone to be stay back in the house and kill time by watching television and they had more chances to frequently visit fast food shops. Their parents could afford the cost of fast foods and they also fulfilled the demand of their children if they had sufficient family income.

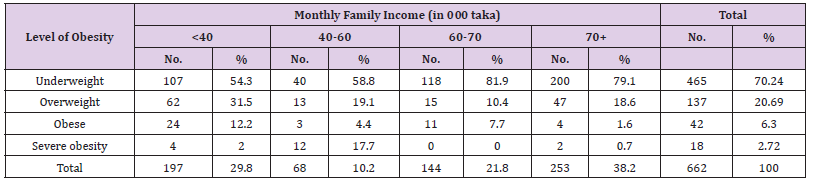

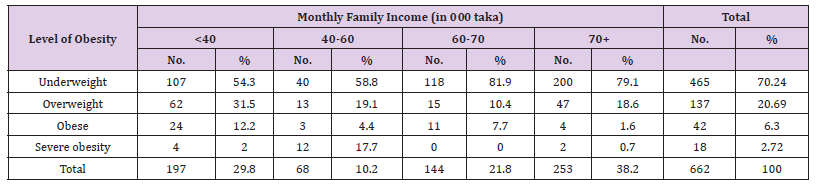

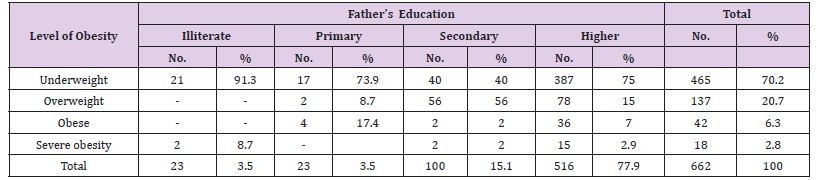

It was observed that the monthly family income of 38.2% families was 70 thousand and above taka [Bangladesh currency] but 79.1 % children of these families were in underweight group (Table 7). It was seen that prevalence of obesity was higher among the children of low income group of families. The relationship was significant in the lower income group of families [χ2= 53.06 with p-value = 0.00]. The family income and food habit of the children and youth was significantly associated (Table 8), [χ2= 94.76, p-value=0.00] income [in 000 taka]. It was seen that 47.9% children and youth took restaurant food. This percentage among the children and youth of higher income [70 thousand and above taka] group of families was 53.8. Family environment is one of the correlates of obesity among children [18]. It seemed that family environment was influenced by parents’ education and occupation. Let us investigate how fathers’ and mothers’ education were associated with children and adolescents obesity. It was seen that (Table 9) the fathers of 77.9 % children were highly educated and 75% children of them were underweight. The percentage of illiterate fathers was 3.5 and 91% children of these fathers are underweight. Both obesity and severe obesity among children of illiterate and primary educated fathers were more (8.7 and 17.4% respectively) compared to the children of secondary educated (2.1%) fathers.

Table 7:Distribution of children and adolescents according to their level of obesity and monthly income.

Table 8:Distribution of children and adolescents according to their food habit and their family income [ in 000 taka].

Table 9:Distribution of children and adolescents according to their level of obesity and their father’s education.

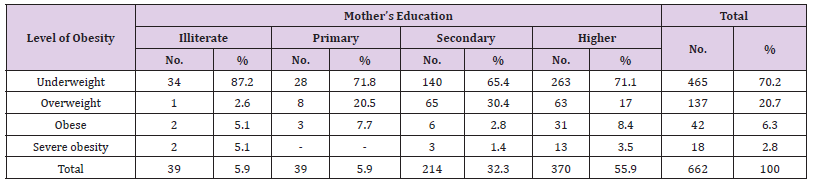

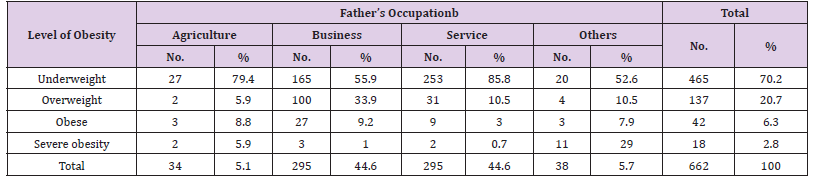

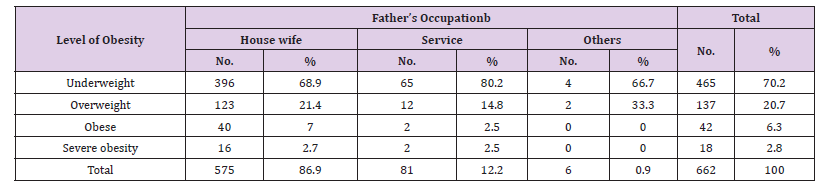

The differential in proportions of level of obesity and fathers’ educational level were highly significant [χ2= 111.70 with p-value = 0.00]. Similarly, significant differentials in proportions of obesity of children according to the differences of mothers’ education were also observed (Table 10), [χ2= 39.23 with p-value = 0.00]. Significant differences in the level of obesity according to the variations in the levels of occupation of fathers (Table 11) were also observed [χ2= 186.02 with p-value = 0.00]. But mother’s occupation was not an influencing factor for the changes in the levels of obesity of children (Table 12), χ2= 10. 50 with p-value = 0.572]. It was observed that most of the socioeconomic variables were associated with level of obesity of children and adolescents. But the degrees of association are not similar. To study the degree of association we had calculated Pearson’s mean square contingency coefficient . The contingency coefficient showed that father’s occupation was the variable due to which level of obesity varied to a great extent followed by father’s education and food habit of the children and adolescents. It was observed that (Table 1) among the male’s obesity and severe obesity were more than their female counterpart.

Table 10:Distribution of children and adolescents according to their level of obesity and level of mother’s education.

Table 11:Distribution of children and adolescents according to their level of obesity and levels of father’s occupation.

Table 12:Distribution of children according to their level of obesity and level of mother’s Occupation

The odd ratio (Table 13) 1.62 indicated that there were 62% more chance for male to become obese and severe obese than the female. Urban children and adolescents had 14 % more chance to become obese and severe obese than their rural counterpart. The odd ratio 0.87 indicated that the children and adolescent of 5 years and above had less chance to become obese and severe obese than the children of under age 5 years. The prevalence of diabetes was 65% more among the obese and severe obese group of children compared to non-obese group of children and adolescents. Those who were T.V viewer for maximum time were 82% more exposed to become obese and severe obese than their counter part who watched T.V. for lesser time period. Restaurant food was not a serious problem for obesity.

This phenomenon was concluded from the odd ratio result 0.82. Children of highly educated fathers were more exposed than their counter parts for whom fathers were not highly educated (Odd Ratio= 1.67). Similar was the case with mother’s education. There were less chance for children of servicemen and servicewomen as obese and severe obese than their counter parts for whom parents were not in service. The level of obesity varied in different degrees with the variation of the socioeconomic variables of the children and youth and of the parents. Thus, we were in search to identify the most important variables for explaining the variation in the data set. This was done by factor analysis. The analysis helps to identify the most important variables to explain the variation in the data set [31] The variables which were included for factor analysis were sufficient to explain the variation in the data set as KMO = 0.63 and Bartlett’s = 1020.732, p-value = 0.000.

Table 13:Distribution of children and adolescents according to their food habit and their family income [ in 000 taka].

The factor analysis had extracted 5 components as first 5 components explained 70.031% variation in the data set. These 5 components along with their coefficients are shown. The higher magnitude of the coefficients indicated the importance of a variable in explaining the variation of the data set. From the coefficients of the variables it was observed that father’s education followed by mother’s education and father’s occupation were most important variables to explain the variation in the data set. The importance of the variables were decided by the magnitude of the coefficients in extracting first component are given below. The first component explained 24.706% variation in the data set.

In a cross-sectional study, it was observed that 81.4% students of the university under study [29] were living in urban area and fathers of around 46% students are highly educated . Almost similar was the case with mother’s education (90%). In the sense of parent’s education and family income, the families of the students could be considered affluent. The present study was done using the data collected from similar type of affluent families. The data were collected from 560 randomly selected families. In these selected families, there were 662 children and youth. These children were privileged group compared to the general children of the country . Our objective was to study the level of obesity among the children and adolescents of affluent families. The study result showed that around 6.3% children were obese and 2.8% belonged to severe obese group. In a separate study [4] it was observed that the proportions of overweight were 2%,11% and 15% among children of age under 15 years, 5-9 years and 10-18 years respectively in the Indian subcontinent [Bangladesh, India and Pakistan] the pooled estimate of obesity was around 6%. But these results were observed among all the children in the country The same percentage in Bangladesh was 7 [32]. The pooled estimate of proportion of obese and severe obese group of children and youth of affluent families was 9.1 %. It indicated that obesity among children of affluent families was an alarming problem. Fathers of most of the children and youth were engaged in respectable profession and higher proportion of them belonged to higher income group.

Majority of the investigated children were males and higher proportion of them were underweight compared to the underweight group among female. As these children and adolescents belonged to affluent families, they had the scope to go to high socioeconomic school in which the expected facilities of physical education exist. But majority of the children were engaged in watching T.V. Very few children were involved in games and sports. Among the urban children risk of obesity was more compared to rural children. The percentage of obese children were lesser in rural areas. This is an environmental effect on obesity as urban children spent less time for physical activity. Similar findings were observed in other studies. [32,33]. This study also indicated that the overweight and obesity were in increasing trend as rates of overweight were less in 2014 [30].

In a separate study [34] it was reported that the increasing trend of obesity was associated with fast foods from restaurant. The present findings were also similar in this respect of association of obesity and fast food from restaurants and visiting the fast food shops was associated with parent’s social status and family income. The offspring from affluent families visited fast food restaurants every now and then and obesity and severe obesity were particularly observed among them. Upward trend in parent’s education and family income were responsible factors for the children’s physical inactivity and their tendencies to watch T.V. and for visiting fast food shops. Factor analysis also showed that parents’ education and fathers’ occupation were the most responsible factors for obesity and overweight of children and youth. As a result, children of affluent families were becoming obese and finally were affected by diabetes. These are grave health hazards with significantly elevated risk of medical and psychological problems [15,17].

Thus, obesity and diabetes are interrelated phenomena, which can start at any time of life. In many instances obesity starts during childhood, unless proper care is not taken for the health of the children and youth. This study also indicated that obesity and severe obesity were more prevalent among the children and adolescents of age 5 years and above. It was observed from the calculation of odd ratio. The children of highly educated parents had the more chance to become obese and severe obese than the children of parents with lower level of education. Restaurant food and higher income in the family were not serious problems for obesity and severe obesity among the children and adolescents as the odd ratios were less than 1 in both the cases. In these two calculations children were classified into two groups. Those who preferred restaurant food belonged to one group. In terms of family income also the children were classified into two groups. The children from families having income taka 70 thousand and above belonged to one group.

The study was conducted among the children and adolescents of some randomly selected affluent [28,29] families of students of American International University –Bangladesh. Most of the children and adolescents were the city dwellers and parents of them were mostly highly educated and were in better economic and social conditions. The study indicated that obesity and severe obesity were significantly associated with parental social and economic status. Factor analysis also showed that parents’ education followed by fathers’ occupation were the most responsible variables for variation of BMI. Again, obesity and severe obesity were related to diabetes and many other non-communicable diseases [35]. These diseases are the major health burden in both developed and developing countries. In a separate study [24] it was reported that most of the NCDs affected people were suffering from diabetes. This is true for both children and adults. In this study also the prevalence rate of diabetes among the obese and severe obese groups of children and youth were observed higher (31.7%). This percentage was 21.9 among the underweight and overweight groups of children.

This is a problem for both parents and health planners. Parents can take care of foods of their offspring. They can choose school for their kids where there is enough facilities for child’s physical education. Government can introduce some regulations so that physical education is a compulsory co-curricular activity of the school. Urban parents should find time to accompany their kids to parks and play grounds at least for some hours in a week. The urban children should be advised to go to the nearby school on foot accompanied by either of the parents or any of the family member. The school authority can encourage the children to take healthy foods which are available nearby school or they may be advised to bring healthy foods to take it during school hours. The children can be advised by the parent and school authority to take active part in physical activity along with sports and games. There should be prohibited regulations not to advertise fast food and candy for their children. Fresh and healthy foods along with physical activities may decrease the rate of obese children, otherwise it will pose a serious hazard to the basic health care delivery system.