Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Man Hon Tang*, Wen Yang Neo, Yang Yang Lee and James Chi Yong Ngu

Received: October 05, 2018; Published: October 10, 2018;

*Corresponding author: Man Hon Tang, Department of Surgery, Changi General Hospital, 2 Simei Street 3, Singapore

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2018.09.001861

Introduction: Small gallbladder polyps (GBP) are usually asymptomatic and benign and are monitored with regular ultrasonography (US) surveillance. Although most centers repeat imaging within a year, there remains no consensus regarding appropriate scan intervals.

Aims: To investigate the size stability of GBP and to review the need for close surveillance.

Methods: All abdominal ultrasound scans performed in our hospital over 3-month period were reviewed. Patients with sonographic evidence of GBP and with subsequent surveillance were included. The demographics of patients, characteristics of polyps, and subsequent scans over the following five years were reviewed. Histological reports were obtained for patients who underwent cholecystectomy.

Results: 96 patients were included in the study. Median age was 51 (range, 24-89) years with a male predominance (67.7%). Main indications for US were hepatitis follow-up (41.7%) and abdominal pain (20.8%). Most patients had multiple polyps (62.5%) and the median diameter of the largest polyp was 4 (range, 3-10) mm. An average of 4.5 scans were performed over five years following detection and most polyps remained stable in size, rarely growing beyond 10mm - only two patients had polyps beyond 10mm. No gallbladder carcinoma was detected during the follow-up period.

Conclusion: GBP usually remain stable in size, seldom grow beyond 10mm, and are rarely malignant. Surveillance scans for polyps smaller than 10mm should not be performed at intervals less than a year.

Abbreviations: GBP: Gallbladder Polyps; CT: Computed Tomography; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; SPSS: Statistics Package for the Social Science

Gallbladder polyps (GBP) are elevated mucosal lesions projecting from the gallbladder wall into the gallbladder interior The majority of GBP are diagnosed incidentally on imaging or histopathologically in cholecystectomy specimens. The reported prevalence of GBP ranges from 4-6% on ultrasonography [1-3] and 2-12% in cholecystectomy specimens [4,5]. Most GBP are benign, the commonest being cholesterol polyps, accounting for 60-90% of polypoid gallbladder lesions. 4% of GBP are adenomas-these are considered benign neoplasms, albeit with malignant potential. Gallbladder carcinoma has been postulated to arise from GBP through an adenoma-dysplasia-carcinoma sequence [6]. Given its dismal prognosis when diagnosed at advanced stages, detection and removal of early lesions offer a curative option for gallbladder cancer [7]. As such, many centres perform close surveillance for GBP, with some advocating 3-12 monthly scans [8-10].

However, recent studies have failed to demonstrate a clear progression of polyps to malignancy over time, and that if gallbladder carcinoma truly arises from polyps remains uncertain [9-11]. Gallahan & Conway suggested that the risk factors associated with developing gallbladder carcinoma are age >50 years, history of primary sclerosing cholangitis, concomitant gallstone disease, solitary gallbladder polyploid lesion, or polyp size >10mm [12]. We hypothesise that GBP do not require such frequent follow-ups. Unnecessary US add to the workload of our healthcare systems and burden patients with rising healthcare costs. Our study hopes to address this issue and suggest a safe interval for GBP surveillance.

This is a retrospective study conducted in an 800-bed regional hospital. All reports and images of abdominal and hepatobiliary system US performed by our Radiology department over a 3-month period were reviewed. Patients with sonographic features of GBP as determined by the radiologists were included in the study. Hospital records were reviewed for patient demographics, past medical history, indication for imaging, US reports, and subsequent outcomes (i.e. surveillance, surgery, death). Subsequent US performed for these patients within this five-year period were also recorded. Patients with no follow-up scans were excluded. Other scan modalities such as computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were also excluded from this study. As this is a retrospective study, scan intervals were determined by the individual attending physician as there are currently no definitive protocols within the institution for surveillance scans. Patients who subsequently underwent cholecystectomy were analysed for operative indications, findings, as well as histology of the gallbladder lesions.

All US were performed by experienced radiologists and vetted by a consultant radiologist. A standard protocol was followed for all examinations. Patients were fasted for a minimum of six hours before US. Scans were performed with patients in either supine position, or when required, in left lateral decubitus. All US were performed with one of three different brands of scanners; Philips iU22 (Philips, Bothell, WA, USA), Toshiba Iplio XG (Toshiba, Tokyo, Japan) and Siemens Sequoia 512 (Siemens, Mountain View, CA, USA) using abdominal, curved array transducers. Diagnosis of GBP was made using standard sonographic criteria: immobile, nonshadowing, hyperechoic lesions attached to the gallbladder wall with no acoustic shadowing [13]. Details of US findings such as number of polyps (single vs multiple), size, presence of gallstones was recorded. The morphology of the polyp was not recorded as it was not consistently reported by the radiologists. When multiple polyps were present, the diameter ofthe largest polyp was recorded. Polyp size from interval surveillance scan were compared with index scans to determined polyp growth. To account for possible inter-observer differences during subsequent surveillance US, polyps were deemed to be stable in size if the maximum recorded polyp diameter is within 3mm of index scan, as the protocol used in previous studies [9,14].

Statistical analysis was performed with Statistics Package for the Social Science (SPSS) version 20. Patient demographics and known risk factors for gallbladder carcinoma were analysed for factors determining polyp stability. Categorical variables were compared using chi-square. Statistical significance is defined by p value of <0.05.

1232 US scans were performed within the study period, with 158 patients found to have GBP. 62 patients had no follow-up scans and were excluded, with 96 patients included in our study. There was a male predominance (7 Male: 3 Female) in our study population. The median age at diagnosis of GBP was 51 (range, 24-89) years old, and ethnic distribution of the study population reflects our local populace, with most patients being Chinese (Tables 1 & 2) details the indications and findings on index US. The main indication for US was for surveillance of hepatocellular carcinoma for patients with viral hepatitis (41.7%), followed by abdominal pain or dyspepsia (20.8%) and GBP surveillance (17.7%). Nearly two-thirds of the patients have multiple polyps found within the gallbladder. The median size of the largest polyp at baseline was 4 mm. 15.6% of the patients also had concomitant gallstones. The majority had polyps less than 10mm (98%). Two patients had polyps greater than 10mm in size - one underwent cholecystectomy while the other died shortly after the scan due to unrelated cause (pneumonia).

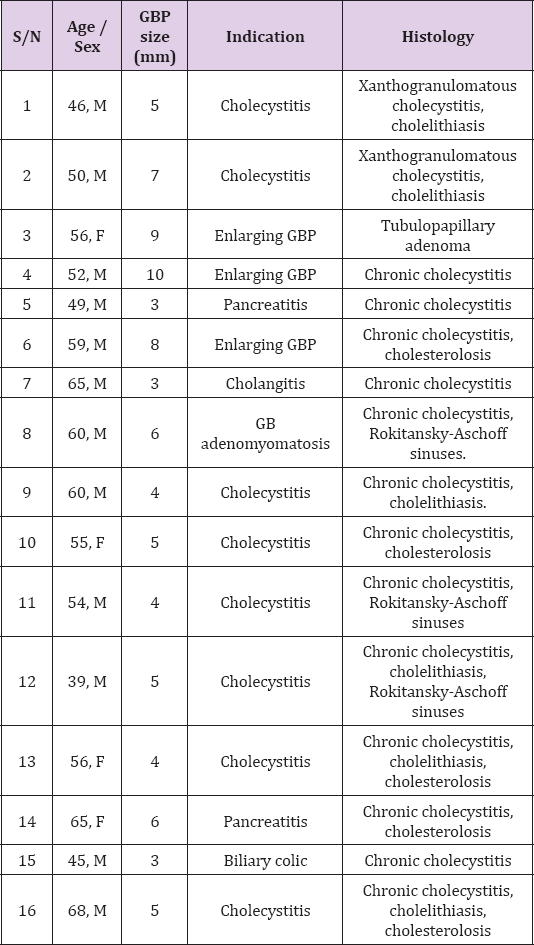

The median follow-up was 50.8 months, with an average of 4.5 scans over the 5-year follow-up period (Figure 1). 85 (88.5%) of these patients were considered to have stable polyps, and none of study population developed polyps greater than 10mm subsequently. Eight patients passed away due to unrelated conditions and no cases of gallbladder carcinoma were detected in the study population during the follow-up period. A total of 16 patients subsequently underwent cholecystectomy. One patient (case 4) had a 10mm GBP found on initial US whilst the other two (case 3, 6) had increasing GBP size on follow-up US and they were advised for surgery. The remaining 13 cases were for gallstone related diseases such as biliary colic, cholecystitis and gallstone pancreatitis. The details of these patients are given in (Table 3). No malignancies were detected in any of the gallbladder specimens.There are no significant differences in age, gender, ethnicity and known risk factors for gallbladder carcinoma between patients with stable and those with enlarging polyps (Table 1).

Table 3: Demographics, size of GBP, indication of surgery, and histology findings from patients with cholecystectomy.

With increasing use of ultrasonography and the advancement of imaging techniques, smaller incidental GBP are being detected more frequently. However, there are relatively limited clinical studies investigating the natural history of GBP. The management of GBP remains controversial - opinions are divided regarding the role of surveillance and indications for cholecystectomy. It remains unclear if all GBP progress to cancer in a manner like colonic polyps. GBP in patients greater than 50 years of age, with concomitant gallstone disease, as well as those with a history of primary sclerosing cholangitis are deemed to be at a higher risk of turning malignant. Some authors have suggested polyp size greater than 10mm as the most significant risk factor for malignancy Other features associated with greater malignant potential include adenomatous polyps, solitary lesions, sessile morphology and gallbladder wall thickening [3,12,15-18]. While consensus supports cholecystectomy for high-risk GBP, most institutions have differing management for smaller low-risk GBP Most intuitions practise interval surveillance for small GBPs with US. However this often poses a clinical dilemma.

Firstly, most GBPs detected on US are in fact cholesterol polyps which poses little risk in becoming malignant. Previous studies have also shown that most small polyps, especially those less than 5mm were in fact hyperplastic or cholesterol polyps on histology [9,10,16,19,20]. Most of our resected gallbladder specimens found no histological evidence of polyps despite US showing otherwise. Moreover, it is often impossible to differentiate between a true adenomatous versus cholesterol polyp based on US alone. In addition, there are currently no strong evidenced-based guidelines as to how frequent the interval for surveillance or the duration of follow-up should be. Our study showed that most of these polyps are less than 10mm and only a small number increases in size over the 5 years follow up, with an average scan interval of approximately 1-year duration. Surveillance scans performed 1-2 years after the index US would not have detected any significant change in these patients. We did not find any risk factors linked to polyp growth within our study population that could help stratify different surveillance protocols. Other studies have also shown that the majority of GBP are less than 10mm in size and showed little change subsequently [3,11,15,21].

A study by a Korean group showed no detected cases of malignancy in small GBP after a median follow-up duration of 72 months.3 Longer follow-up studies of GBP by Kratzer et al and Eelkema et al showed no cases of gallbladder malignancy after 7 and 15 years respectively [11,16]. However, due to the perceived association between polyps and carcinoma, some authors are strong advocates of close annual or even 6-monthly surveillance scans [8-10]. The significant number of patients without any follow-up US that were excluded in our study reflects the clinical conundrum where there is a lack of definitive surveillance protocol and that GBP are often managed by more than one discipline, i.e. surgical and medical. The higher proportion of males detected with GBP probably stems from a selection bias in our population group as a significant proportion of the scans performed were for surveillance of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with hepatitis, which is more prevalent within the Chinese male population. Our study suffers from the usual limitations of a retrospective analysis. Another issue would be the accuracy and reproducibility of US measurements for GBP. While specificity of US for GBP is high (94%), sensitivity ranges from 34-90%, with the presence of gallstones greatly affecting the accuracy of the scan [18-25].

Nonetheless, it remains the diagnostic modality of choice for GBP as it offers good spatial resolution compared to CT and MRI. US can detect movement, which helps to differentiate polyps from stones. It is also cheaper, making it more suitable for long-term surveillance. In conclusion, our study shows that the majority of GBP are smaller than 10mm and they rarely grow significantly or turn malignant in the short term. Current scientific evidence and opinions dictates that we should offer surveillance for GBP; however our results suggest that a surveillance interval of 1-2 years is reasonable for low risk GBP. Data from longer follow-up may potentially support the practice of discharging patients with small GBP without any form of surveillance.