Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Maruf Hasan1,2, Abrar Wahab1, Mohammad Alam1 and Ahmed Hossain1*

Received: August 21, 2018; Published: August 28, 2018

*Corresponding author: Ahmed Hossain, Department of Public Health, North South University, Bangladesh

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2018.08.001654

Background: Surgical site infection (SSI) is the dominant cause of unplanned and potentially preventable hospital readmissions in surgical patients. The main objective of this study is to determine the risk factors of SSI among patients undergoing inguinal hernia operation.

Materials and Methods: We conducted a hospital-based case control study from March 30, 2017, to November 29, 2017, on a total of 176 patients undergoing inguinal hernia operation in a public Hospital of Dhaka. We used a semi-structured questionnaire to collect data on patients' characteristics and a checklist containing three questions to identify the SSI.

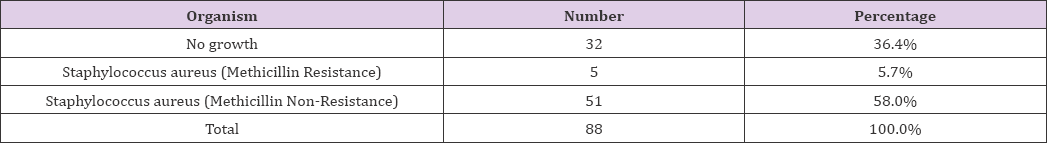

Results: The mean age of the study population was 42 years among case group and 44 years among the control group. The multivariate analysis reflects the risk factors associated with SSI are age of above 35 years (OR= 3.84, CI=1.41-11.39), day-labor (OR= 3.032, CI = 1.23-7.79), employed (OR = 3.650, CI= 1.16-8.46), and having diabetes more than 5 years (OR= 4.160, CI= 1.54-13.26). We also found 5.7% of cases showed Methicillin Resistance Staphylococcus Aureus growth, and 58.0% of cases showed Methicillin non- Resistance Staphylococcus aureus growth.

Conclusion: The identified risk factors for the SSI reflect a complex interaction among socio-demographic conditions. Although further study is warranted to validate these results, the socio-demographic factors presented may be a useful tool to stratify patient risk of SSI.

An inguinal hernia is a protrusion of abdominal cavity contents through the inguinal canal. Usually an inguinal hernia gets worse during the day and improves at night when lying down. Initially, it produces severe pain and tenderness of the area [1]. Inguinal hernias are the most common form of abdominal wall hernias, and it is the most common surgical pathology [2]. The risk of getting inguinal hernia repair is estimated to be 27% for men and 3% for women [3]. About 500,000 cases come to medical attention each year in the United States [2]. The incidence of the total annual need for inguinal hernia repair in rural sub-Saharan Africa is estimated to be a minimum of 205/100,000 population [4]. The inguinal hernia operation causes SSI infection which may lead to a fatal outcome [5]. Inguinal, femoral and abdominal hernias resulted in 51,0 deaths globally in 2013 [6]. Surgical site infection (SSI) is the most common nosocomial infection among surgical patients which accounts for 38% of postoperative complications [7]. It is the dominant cause of unplanned and potentially preventable hospital readmissions in surgical patients [8], which results in apparently 20,0 potentially avoidable deaths per year [9]. These infections occur in an increase in morbidity, duration of hospital stay, healthcare expenses, and mortality [10-11].

In the United States alone, these complications translate into additional health-care costs more than three billion dollars per year [9]. In general, antibiotics are being used to treat most SSI, but patients with SSI may need another surgery to treat their infection [12]. The prevalence of occurring SSI in patients undergoing surgery is 5%, which may cause much morbidity and on a rare occasion, it can be fatal as well. Other patient-related factors are; low serum albumin concentration, obesity, older age, diabetes mellitus, ischemic heart disease, and smoking. Potential risk factors also include prolonged procedures and inadequacies in either the surgical scrub or the antiseptic preparation of the skin [13]. Microorganisms on the patient's skin and the alimentary tract or female genital tract are the most common sources of infection [13,14]. The most prevalent bacteria to be isolated is Staphylococcus aureus, which often is found to be resistant to methicillin or other classes of antibiotics given at the time of operation [13]. As laparoscopic surgeries are less common in inguinal hernia surgery in Bangladesh, it is essential to identify the factors related to open inguinal hernia repair surgery and to minimize them. So far, nationally representative data on factors related to SSI on inguinal hernia surgery are not available in Bangladesh. Therefore, the study aimed to investigate the potential risk factors associated with SSI in inguinal hernia surgery.

The study was conducted from March 30, 2017, to November 29, 2017, in Kurmitola General Hospital which is a public hospital located in the capital city of Dhaka. As of 2017, it has a bed capacity of 500, and at present, it serves about 4000 outdoor, and 400 indoor patients daily. The study sample size was determined using the difference in proportions formula. The assumptions used for the sample size calculation are; desired power (80%), level of statistical significance (1.96), the ratio of controls to cases (1:1), the proportion of cases exposed (assumed 33%), and proportion of controls exposed (assumed 20%). Therefore, the required sample was 88 cases and 88 controls.

a) Cases were patients undergone inguinal hernia operation and develop SSI within 6 weeks.

b) Controls were patients undergone inguinal hernia operation but did not develop SSI within 6 weeks of their operation.

c) Age: 18-64 years old.

Exclusion Criteria

a) Patient with more than one surgery including inguinal hernia operation.

b) History of having other infectious diseases like AIDS, TB, Syphilis, Hepatitis B, & Hepatitis C infection.

c) Patients with incomplete data or history sheet.

d) Those who were not willing to participate in the study.

We used a structured questionnaire to collect information on age, sex (male or female), occupation (unemployed, employed or day-labor), duration of diabetes (No diabetes, < 5 years and >= 5 years), marital status, education, ischemic heart disease (yes or no), and use of antibiotics within 3 months of the surgery (yes or no). The use of antibiotics was measured by the question "Did you take any antibiotics during the last three months before the surgery?".

We performed a checklist for the identification of cases. That checklist consisted of 3 questions, and those were "pain with redness (+,-) at the surgical site," "drainage of fluid from the wound" and "fever." For a positive response of each question gave 1 score and for negative response of each item gave 0 scores. With a total score of 3, we have determined if the patient had SSI or not. If the patients had SSI then, pus or the fluid was sent for an antimicrobial resistance test.

After collection of data, all interviewed questionnaires were checked for completeness, correctness and internal consistency to exclude missing or inconsistent data. Statistical analysis of the data was conducted using R. Descriptive analysis was computed as a percentage for categorical variables and means for continuous variables. Unadjusted odds ratio, adjusted odds ratio, and their 95% confidence intervals [CIs] were used as indicators of the strength of association. Multivariate analysis was carried out using logistic regression to examine the relationship between dependent variable and independent variables.

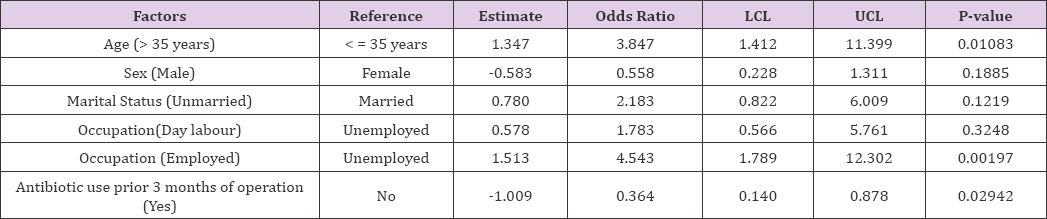

About 88 cases and 88 controls consented to participate in the study and fulfilled the eligibility criteria. The mean age of the study population was 42 years among case group and 44 years among the control group. Our descriptive analysis illustrated the ratio of male and female in case group was 76.2% and 23.8% respectively, and similarly, in control group, the ratio was 70.5% and 29.5% (Table 1). It appears from the boxplot of age that the occurrence of SSI is increasing as the increase of age. Our descriptive analysis also showed, no bacterial growth was found for 36.4% cases, 5.7% cases showed Methicillin Resistance Staphylococcus Aureus growth, and lastly, 58.0% cases showed Methicillin nonResistance Staphylococcus aureus growth (Table 2). The patients' characteristics and unadjusted analysis are presented in Table 2. Among these covariates day labor (OR= 3.032, CI = 1.23-7.79), employed (OR = 3.650, CI= 1.16-8.46), and duration of diabetes (OR= 4.160, CI= 1.54-13.26) were found significantly associated with the SSI according to the values of the unadjusted odds ratio. It appears that patients with more than five years of diabetes are at four times more risk of getting SSI compared to patients without diabetes. A multivariate logistic regression model was fitted after adjusting the extraneous variables, as presented in (Table 3). The risk factors for SSI were found as Age and Occupation (employed). It appears that participants older than 35 years old are 3.84 times more likely to have SSI while undergoing an inguinal hernia operation than compared to the participants with the age of 35 years and less (OR= 3.84, CI=1.41-11.39). The study suggests that participants who are employed are 4.54 times more likely to have SSI compared to the participants who are unemployed (OR= 4.543, CI= 1.78-12.30). Our study also suggests that male participants are at 55% lesser risk of getting SSI during their inguinal hernia operation compared to female participants (OR= 0.558, CI= 0.221.31), though we have not found any statistical significance for this result. From our multivariate analysis, we also observed the use of antibiotics prior to the inguinal hernia operation acted as a protective factor (OR= 0.364, CI= 0.14-0.87) which indicates the patient who took antibiotics before the operation are approximately 60% less in risk of developing SSI.

Table 2: Organism detected in culture and sensitivity test from the pus collected from the site of infection of the cases.

Table 3: Adjusted relationship between covariates and case-control that is analyzed by multivariate logistic regression model.

Note: LCL 95% lower confidence limit for OR UCL 95% upper confidence limit for OR.

Our study showed that multiple factors are contributing to the development of SSI after an inguinal hernia operation. This analysis disclosed three independent risk factors for SSI: duration of diabetes, age, and occupation. Our study posited that patients with more than six months of diabetes were at more risk of developing SSI. In a systematic review and meta-analysis considered diabetes as an independent risk factor for SSI and diabetes patients undergoing surgery were 50 percent more likely to develop an SSI [15]. There are other studies which also found diabetes as a risk factor for the development of SSI [16-18]. Older age is a known independent risk factor for the development of SSI after inguinal hernia operation [19,20]. Our study also illustrated that participants with the age of more than 35 years old were more likely at risk of having SSI after an inguinal hernia operation. In a recent retrospective, case-control study found that the age of > 65 years old as an independent risk factor and the rate of SSI increased for each decade of increasing age [18].

There are not so many studies that explored the relationship of occupation with SSI. However, there was a finding in a prospective cohort study where it mentioned that wound care has possibilities to be hampered among employed persons [21]. In our study occupation was also found as another significant risk factors for SSI. This result could be due to the fact that people who are day-labor or employed, they remain in a rush to get back to their work just right after their surgery without any prolonged rest and because of this the wound care becomes affected which opens the door of SSI among these people. Therefore, it is particularly important that health care providers make their patients more cautious about their wound care.

This study finding should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, we conducted this study in a single hospital with relatively smaller sample size. Second, few of the patients had incomplete history sheet, and incomplete directory needed extra afford for the fulfillment. Third, after analyzing our data, we found that the variable of taking antibiotics three months prior to their operation acted as a protective factor. So we would advise researchers to exclude this type of patients from their future study Finally, the time for the study was comparatively limited. Thus, the more illustrated research should be carried out in future including various regions of the country and with more samples from broader background and study should be done in depth.

This study suggests few socio-demographic factors that are associated with the SSI among adults in Bangladesh. Our study showed the history of diabetes and age of > 35 years old increases the chance of developing SSI significantly. But the highlight of this study is that over 60% of patients who were employed and day-labor had SSI after the surgery, which indicates occupation as an important factor in developing SSI. This probable risk factor has not been explored in any research study till now. So our recommendation to the health care providers and surgeons that this group of patients should give attention with care while undergoing an operation. Although further study is warranted to validate these results, the identified socio-demographic factors may be a useful tool to stratify patient risk of SSI.