Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Nampala MP*

Received: May 28, 2018; Published: June 20, 2018

*Corresponding author: Nampala MP, Regional Universities Forum for Capacity Building in Agriculture (RUFORUM), P.O. Box 16811, Wandegeya, Kampala, Uganda

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2018.05.001266

This paper, presents a critical evaluation of Uganda’s health system with a justification using literal examples and illustrations based on key indicators of the selected relevant evaluative criteria. The aim of the paper is to present an assessment of the extent to which Uganda’s health system is effective in achieving its goals. Evaluating health systems is like measuring the social impact, which is difficult but necessary. Uganda’s Health System, like other systems, aims to achieve and sustain good health and well-being of its people. This is a formidable task that remains elusive but there are indications of progress in the positive direction. The Health System has been evolving over the last 3 to 4 decades to handle traditional (malaria), emerging and re-emerging (HIV-AID) as well as sporadic outbreaks (Zika, Ebola and Marburg) challenges that continue to escalate the disease burden and health situation in the country. Attainment of the broad purpose of a health system necessitates multi-stakeholder engagements in efforts to address the complexities in the system. Having many players working towards better health, good organization is paramount. The Uganda health Sector Strategic Plan is among other things, designed around a basic minimum health package, which targets cost effective interventions at the heaviest disease burdens. An important implementation problem of the Health Sector Strategic Plan (HSSP) is the chronic and substantial under funding of the health sector.

Keywords: Disease Burden, Malaria, Sporadic Outbreaks, Uganda

Abbrevations: HSSP: Health Sector Strategic Plan, GAVI: Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunizations

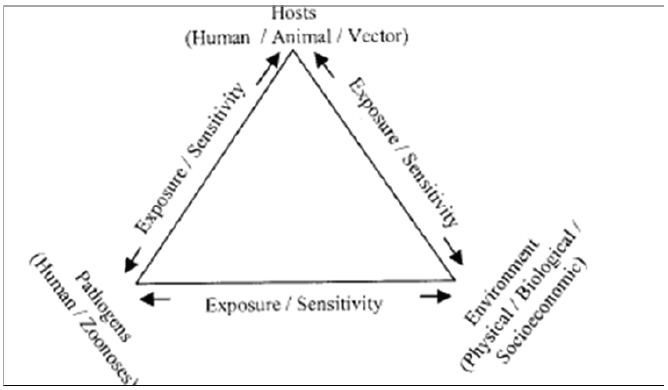

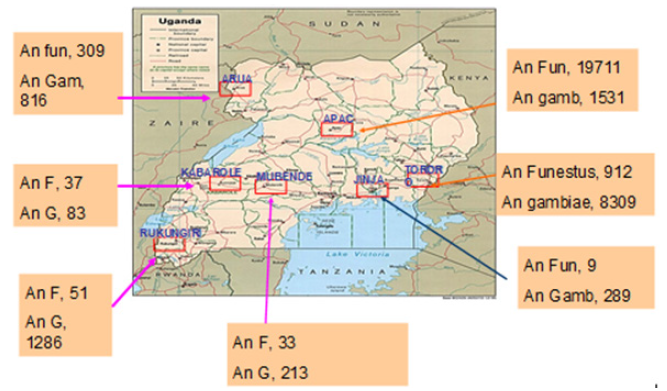

The Republic of Uganda is a former British colony and landlocked country in East Africa, with a population of 32 million and land mass of 236, 040 square kilometers [1]. Uganda is a tropical country that lies within the East African Great Lakes Region and this geographical location and demographic factors are central to the shape and focus of the national health system [2]. For instance, the “Disease Traingle” which entails the causing agent (pathogen) interaction with host organism and the environment as illustrated see Figure 1 adopted from [3] has in the past favored sporadic outbreaks of Ebola, Marburg and Zika viruses which cause hemorrhagic fevers that were effectively curbed [4]. The tropical environment is ideal for malaria, which remains the leading cause of morbidity and mortality with the malaria vector varying depending on the climatic zones as indicated in Figure 2 [5]. These facts and indeed the growing disease burden arising from emerging and re-emerging major infectious and non-infectious diseases as well as other threats to health and well-being in Uganda are important considerations in the design and implementation of National Health System. Health system according to [6] entails all organizations, institutions and resources dedicated to securing health and well-being.

Figure 1: Illustration of a host -pathogen -environment framework for the assessment of risks to humans from vector-borne diseases under global change.

Figure 2: Map of Uganda showing malaria vector (Anopheles gambie and Anopheles funestus) distribution.

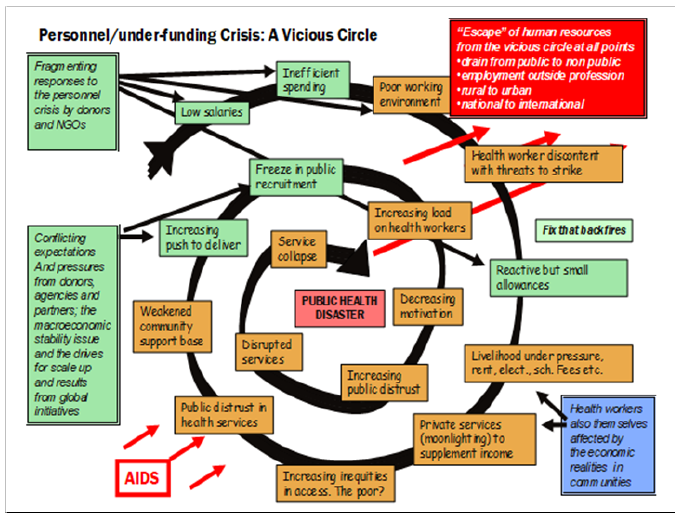

This definition encompasses health actions and non-health actions within and outside the Health Sector that lead to desired health results [6]. Uganda’s health system has predominantly remained focused on healthcare aspects with emphasis on curative measures and not public health measures. This corroborates the paradox of health policy discussed [7]. The main factors in the evolution of Uganda’s health systems in the last four decades include external influences (including colonialisms and global agenda for health); governance, stewardship and leadership; conflicts and civil strive; funding; emerging challenges and burden of disease; and policies [8,9]. Uganda’s healthcare system works on a referral basis; if a level II facility cannot handle a case, it refers it to a unit the next level up. Often units don’t have the essential drugs, meaning the patients have to buy them from pharmacies or other drug sellers. This has resulted in an emerging lucrative private healthcare (Figure 3). Presents a summary of the Health System in Uganda, which is characterized by functions presented in Table 1. The goals of Uganda’s Health System is “Attainment of a good standard of health by all people in Uganda, in order to promote a healthy and productive life”; while the objective is “Reduced morbidity and mortality from the major causes of ill-health and premature death, and reduced disparities therein”

A relevant criteria for evaluating any healthy system, are presented below, should focus on the relationship between the functions and objectives of that health system (Figure 4). Uganda’s National Health Policy addresses aspects of the social determinants of health and is focused on reducing poverty through promoting people’s health [1], it covers aspects of health and not just disease and illness [10]. Based on national aspirations for the health sector, Uganda has a Health Sector Strategic Plan designed with a clear log frame matrix with indicators and milestones and associated aspects of quality, quantity and time [1]. Despite, arguments that strategy is not planned but emerges within organizations as they respond to demand forces, strategy plans are consensus views by various stakeholders that define direction of the entity and how the stakeholders will work in partnership to get there [11]. For Uganda’s Healthy System, the HSSP indicators and milestones are a key tool in the criteria for assessing and monitoring; and these include among others, the following:

This is a process by which an organization establishes considerations within which programs, investments, and acquisitions are reaching the desired outcomes. The process of measuring performance often necessitates the use of statistical evidence to determine progress toward specific defined objectives [12]. Many donors have tried to address concerns of aid effectiveness and have provided budget support in healthcare on a performance based approach. For example, the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunizations (GAVI) implements a “reward for performance,” through which it provides incentives for expanded coverage in two ways. First, GAVI ceases funding if countries do not achieve specified immunization coverage targets. While many donors make this pledge, GAVI is an exception in that it carries it out.

In late 2003, it terminated grants to 10 countries that had failed to achieve specified goals, with Uganda being one of the ten countries. It has also increased funding for 23 countries that achieved their immunization coverage goals. Second, in some programs it directly rewards performance by simply paying $20 per additional fully immunized child. Half of the money is paid in advance, with the remainder paid upon proof of immunization. There are no strings attached to the use of the funds, other than showing proof of having achieved specified immunization targets. The problem with performance-based criteria, is that failure is usually punished severely therefore, the there is a tendency for healthcare organizations to hide it [13]. Despite this short coming with the pay for performance criteria, Uganda has adopted the approach. The Central Government (Ministry of Health) is now paying health service delivery system at the District Level for results/outputs indicators (services actually delivered, coverage, lives saved, households visted, etc).

This involves people and systems and entails employees working to implement and achieve their plans which in turn translates into achieving those of the particular health organization; and achievement of health organization plans contribute to achievement of overall objective and goal of the National Health System.

A functional health system should deliver intended objectives and goals. The possible indicators for measuring effectiveness in this respect can be tailored to specific sub-sector components and may include positive health-enhancing behavior such as child spacing and level of client appreciation of services offered [14].

This entails ethical issues such as autonomy, respect and confidentiality of mothers, children and/or families. It also involves customer care attributes such as attention accorded to patients, quality of services offered and ability to make choice.

Saving lives depends on high coverage, which fortunately is in-built in the continuum of care that ensures that the health care package can be delivered by family, communities, outpatients, outreach and clinical services. This approaches increases accessibility. Nevertheless, as indicated by [15] the shift in health systems towards profit maximization blocks access to services.

According to [10] health is a right to all. Thus, the Uganda Health system should strive to ensure that each Ugandan should receive healthcare services according to their needs while contributing according to their ability and resources at their disposal.

This entails focusing on desired outputs while implementing the “right interventions rightly”. Using vertical strategies which focus on specific ailments integrated with horizontal ones which aim to enhance the overall structure and functions of delivering health services may increase efficiency at a fraction of the cost. Cost-benefit and marginal analysis can be used to assess the cost of interventions against derived benefits.

This entails indicators such as the actual services that are approved and adopted as relevant within the context of users. In maternal, newborn and child health, this would for example entail packages comprising specific proven interventions such as Kangaro Mother Care that aim at saving lives of newborns integrated with other supportive interventions (such as maternity policies) according to local needs and capacity [16]. As observed by [15] social, economic and political interventions are prime and should therefore be part and parcel of the context within which public health interventions and services are evaluated.

From the above criteria, Uganda’s Health System is characterized by the following strengths:

a) Client focused: Understanding stakeholder needs and giving attention to their priorities; being accountable to the stakeholders at all times; fostering a rights based approach, social justice & equity

b) Professionalism: Having professional demeanor and conduct, integrity in all actions, time management, mutual and self respect, as well as the requisite technical competences

c) Teamwork and partnerships: Defined by team members who practice openness, transparency, flexibility, loyalty and trust

d) A learning Organization: Embracing change, commitment to continual improvement, sharing knowledge and best practices

e) Research and-Evidence-based: the strategic action are based on existing knowledge taking into consideration contextual issues

Typical of health systems, it has several stakeholders with varying influence on the achievement of organization aspirations. It has greatly benefited from leadership and the influence of leaders.

Implementation of the well articulated strategic plan that is intended to drive the health systems agenda is constrained by inadequacies including:

a) Depletion of health workforce in numbers and skills at all levels of service delivery.

b) Leadership, Management, Specialist and other important skills are in short supply at all levels of health care. Capacity building is curtailed by high levels of attrition. Investment in training is low; recruitment and retaining of staff is poor; deployment of staff is difficult; migration of health workers is on the rise; demoralization due to work overload is common. Restrictions on recruitment and low salary packages

c) A low Health Sector budget leaves many interventions unfulfilled or unattended to resulting in the public health challenge that is apparent in Uganda (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Undesirable Health outcomes arising from the Personnel and under funding crisis (Source WHO, 2006).

d) Uganda’s Health Sector Strategic Plan articulates relevant issues and has promise to deliver health and well-being to the population. However, the focus remains on curative medicine and not public health to prevent disease. This is in part due to limited personnel and financial resources.

e) As indicated by [7] the reluctance to embrace public health measures is probably due to the fact that the disease burden due to emerging communicable diseases remains apparent and drug therapies will provide quick results while ecological management or life style changes are likely to take far longer to reveal their effectiveness and desired impacts. However, the inability to get things done has also been observed to constitute policy failure which is a result of non-implementation or unsuccessful implementation [17,18]. For non-implementation, a policy is not put into effect as intended while the situation on unsuccessful implementation occurs when a policy is fully executed but fails to deliver intended results. The health system in Uganda suffers from both facets of policy failure. For example, the Food and Nutrition Policy enacted suffers from limited implementation of otherwise useful provisions while policies on home-based management of malaria have been implemented but intended results remain elusive.

f) The prevailing shift to the private-public mix which breeds a spirit of entrepreneurship, competition and market values undermines attempts to secure fairness and equity in delivery of health services. The focus on markets may not allow for responsiveness on the part of the individual but for responsiveness on the part of national governments which according to is a shift from planning according to [15] need toward demand in the market [19-24].

Clearly, there are methodological challenges in measuring effectiveness of health systems interventions. Differences at the national level due to various factors present complex environments for which evaluation of health systems goals is not straightforward. Simple tools such as cost–benefit analysis, logical frameworks, traditional project management tools and others may not work on their own, as they fail to take into account the existing complexity [15] disputes the use of compound and /or synthetic indicators (e.g., disability, well-being) and advocates for simple and easy to obtain indicators (e.g., proportion of communities with access to clean drinking water).

This work was part of a series of Individual Projects by the author during Masters of Public Health Class at the University of Liverpool, UK. Support rendered by faculty at the University of Liverpool is greatly appreciated.