Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Irfan Ullah1*, Abbas Ullah Jan1, Syed Atta Ullah Shah1, Muhammad Ishaq2 and Ghaffar Ali1

Received: June 01, 2018; Published: June 20, 2018

*Corresponding author: Irfan Ullah, Department of Agricultural & Applied Economics, The University of Agriculture Peshawar-Pakistan

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2018.05.001265

This paper aims to examine the food consumption decisions of households in Pakistan to understand the demand for different food commodities and to determine the effects of important economic factors such as prices and income. Linear Almost Ideal Demand System model is applied to estimate food demand patterns using the Household Integrated Economic Survey of Pakistan for the year 2011-2012. Food products are categorized into fourteen groups including milk, vegetables, sugar, rice, fruits, beverages, wheat & wheat flour, other cereals, pulses, oil & fats, tea & coffee, backed products and other food. Economic factors such as food commodities price and household’s income and their socioeconomic and demographic characteristics are included in the model. Prices of basic food items such as wheat & wheat flour, baked products, milk, meat, fruits, vegetables, beverages, rice, other cereals, pulses, oils & fats, tea & coffee and baked product should be kept constant. Imposition of any sale tax could create huge loss in consumption for these commodities. The uncompensated own price elasticity of demand for milk, meat, fruits, rice, other cereals and backed products are more elastic to food expenditures and can be categorized as luxury goods. As the demand for milk, meat, fruits, rice, other cereals and backed products are more elastic to total food expenditures (income). Imposition of any income tax on household personnel income could reduce their consumption of these food groups. Such policies could result food security problems for low & middle income households in Pakistan.

Keywords: Demand System; LA/AIDS; Food Demand Elasticities; Expenditures Elasticities; Pakistan

Abbrevations: IFPRI: Index of International Food Policy Research Institute; FAO: Food and Agriculture Organization’s; LA/AIDS: Linear Approximate Almost Ideal Demand System; HIES: Household Integrated Economic Survey; PSB: Pakistan Bureau of Statistics; PSLM: Pakistan Social and Standard Living Measurement

Being a developing country, Pakistan is ranked as sixth most populous country of the world with the population growth rate of 1.92 percent. The estimated population is 191.71 million of which 116.52 million (60.78%) reside in rural and 75.19 million (39.22%) in urban areas [1]. Statistics of daily income outlined by World Bank analysis reported that $ 1.25 per adult/day, which alarmed that 21.04 % of the whole population living below the poverty line. In the prevailing circumstances, in almost all the fundamental necessities food security top the list of immediate concerns. Government of Pakistan kept the food security policy from last several years as a dominant component of national agenda although the performance of agricultural sector has been encouraging with a growth of 2.1 percent during 2014-15 [1]. Food is a crucial need to bear life and to meet a successful growth. The world has progressed through hunter gatherer, agricultural and industrial stages to provider of goods and services. However, many of the today’s world have limited access to food, causing food insecurity, particularly in the developing countries. Food and nutritional insecurity in Pakistan is on the rise. Despite being an agrarian economy, more than half of the Pakistani population go hungry to bed, while 40% of children below the age of 5 are stunted [2].

Pakistan has attained notable improvement either from local production or imported edible product to maintain food stock, but still food shortage is a repeated phenomenon and government is facing challenges of feeding accumulated population year by year. The mismatch between population and availability of food also affected food pattern in the country. Food insecurity is a very consistent challenge for a country like Pakistan due to its annual population growth rate and lack of advancement in agriculture sector, which created an inverse relation between population and the food produced. International inflation in food stuff prices and failure in achieving food limits of Pakistan due to frequent natural disasters brought the country on the verge of dangerous situation (WFP, 2011). Hunger Map of Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) and Hunger Index of International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) suggested a serious prevalence of starvation and hunger in Pakistan if proper precautions shall not adopt timely [3]. Hygienic and nutritious food in adequate amount can only enable nations to perform their functions efficiently, to achieve their goals and bring the country on the path of prosperity and development. Almost all the western and northern countries of the world are well developed as due to their self-sufficient in food they required. Pakistan is currently facing the challenge of food insecurity and also has to face it in future if policies would remain the same. If food demand and supply gulf has been wide of a country then ultimately its economic growth, poverty alleviation and development should be affect negatively. In order to bring all these developments in hands Pakistan need to match the supply of food with the population demands at an easy access for poor’s.

Pakistan is at the verge of eleventh hour which has need to determine the magnitude of its actual food demand while keeping population growth under prior consideration and also depict the major obstacles which handicapped its agricultural prosperity. All the available opportunities and every inch of agriculture land should be utilized with modern but friendly techniques to overcome the increasing demand of food which at the other side also minimize the imports and shall provide relief to local people through low prices and to government as well. Applied research should be conducted to gather information regarding the constraints and future policies should be based on gathered information, these researches are the source way through which government can set a prediction of food demand and supply, levy and subsidies etc to uphold more production and many times intervene in market to stabilize the prices. Government policies implications influence the producers, traders and consumers in a peculiar way which may encourage or discourage them for the future planning. However, different stakeholders and non-state actors may response not in the same way [4].

Consumer behavior is of more importance with respect to the interventions and policies infiltrate by the government, so whatever these policies are, it is vital to investigate the impact of such interventions on demand for food of the population, to tackling future challenges and best utilization of the opportunities adhere to agriculture sector. In Pakistan, both in urban and rural areas poverty is a common phenomenon of large population whose major part of income (80.42%) is consumed by food in contrast of other household expenditures. In 2013-14 these expenditures were controlled and were brought down in urban and rural areas upto 43.63% from 45.01% in 2011-12. Major portion of food expenditures was spent on sugar, vegetable ghee and vegetables, milk and wheat which almost share the burden of 54.75% of 80.42%. whereas, the poorest spend 65.63% of their food expenditure on milk, sugar, wheat, vegetable, and vegetable ghee in contrast to the richest who spend 58.54% on milk, vegetables, wheat, fruits, sugar, mutton, beef, chicken etc. This also shows the differences in both the rich and poor classes’ preference towards food, therefore, differences in classes and high prices may affect supply and demand of food and also restrict the approach of poorer to quality food [1].

The parameters of progress and development of any country is associated with the consumption by the way of measuring the welfare of the overall population and their purchasing capacity for various daily use items and other standards of life. In fact consumption activity may call the backbone of all the supply and demand and all sort of investment is evolving around it directly or indirectly. Food accumulated the top priority as it is being the basic need to sustain life of individuals especially for the poorer. Since the guesstimates about the purchasing power of food are required to design a batter food policy to set priorities, understanding the relationship between household consumption and income provide acumen for consumer behavior. It is important to derive and gauge the food demand of each household to target the aggregated demand and identify the challenges and opportunities associated with the agricultural sector in the country. Such research endeavor is of paramount importance to develop policy alternatives and generate informed policy decisions. The consumption and production decisions are usually driven by government policies such as fixing production targets, imposing taxes, announcing incentives (subsidies) to promote production and sometimes intervene in market to regulate prices. These policy implications have great influence on consumers, producers and trade alike. However, different stake holder’s response differently to such decisions [4].

To know the effect of such interventions on food consumption decision of the population and to get insight into the challenges and opportunities associated with agriculture sector, it is imperative to study consumer behavior regarding food consumption. Keeping in view the importance of food consumption in the economy the main aim of this paper is to analyze food consumption pattern of households in Pakistan for aggregated food groups based on the HIES 2011-12 data by applying the Linear Approximate Almost Ideal Demand System (LA/AIDS) developed by [5,6]. All the expenditures, uncompensated, compensated own and cross price elasticities are estimated by using the LA/AIDS model. The reminder of the paper is arranged into four sections. Methodology and data needed for the estimation of the uncompensated, compensated and expenditures elasticities is discussed in section two. Empirical results are briefly discussed in section three and the last section of this paper is composed of conclusion and policy recommendations.

Demand analysis requires selection of realistic demand function and complete and accurate data. For this study detail selection of demand model and data used are discussed in the following sub section. The Linear Approximate Almost Ideal Demand System (LA/ AIDS) model is used to estimate the expenditures, uncompensated and compensated demand own and cross price elasticities. The LA/AIDS satisfies the axioms of consumer’s choices, provide first order approximation and allows for interdependence among products [7]. Expenditure/income, uncompensated and compensated own and cross price elasticities were estimated through the use of Linear Approximate Almost Ideal Demand System. The LA/ AIDS provide the first order approximation to the expenditures functions and satisfies the axioms of consumer choices and allows for investigating interdependence among products [5-7] used the flexible expenditure function with Price Independent Generalized Logarithmic preferences to derive the LA/AIDS having many desirable properties to estimate the demand system. With simple parametric restrictions like symmetry and homogeneity the AIDS model automatically satisfies the aggregation restrictions. In budget share the LA/AIDS can be given as:

wi=αi+ Σj γijln pj+βjln(x/p)+μi (1)

The parameter αi, βi and γij needed to be estimated. Pj is the prices of good j. Budget share of good i is wi and x is the total expenditures. The aggregated price index P is shown by Laspeyres Price Index which is defined by ln(p L )= Σi w1−ln(pi ) , ln is the natural logarithm and n represents number of goods. Where γij =1/2 ( γij + γji ) = γjifor two goods i and j. Given an optimal allocation on food expenditures, when relative prices of individual food change the consumers modify their optimal food consumption by imposing separability at food level. The marginal rate of substitution between any food items is independent of the changes in the non-food items and appropriate information regarding each budgeting stage can be obtained through separability restriction.

Using the relationship proposed by Pollak and Wales (1971 and 1981) equation 1 is augmented with household specific demographic, socioeconomic and regional characteristics.

Where δ_(ir ) is the vector of parameters and η_r is a matrix of socioeconomic variables. The demographic variable included in the model: age, family size, marital status, dummies representing the urban and rural regions and the provinces of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Punjab, Sindh and Baluchistan is taken as reference province. Binary variable is equal to 1 if the phenomenon exists and 0 otherwise (e.g. if a household is married then it is equal to 1 otherwise, 0). In this research study, socioeconomic characteristics included in Equation 1 become as follows:

Where αi*** =αi** −Σk δik ηk . The complete demand system that use dummies and the demographic variables is the same as the single equation model. Equation 3 is estimated for overall Pakistan. The budget shares and the price included in equation 3 are for fourteen food groups: milk, meat, fruits, vegetables, beverages, sugar, wheat & wheat flour, rice, other cereals, pulses, oil & fats, tea & coffee, backed products and other food.

The theoretical restrictions i.e, adding up, homogeneity and symmetry imposed during the estimation process is as follow.

Where the number of demographic and other dummies is represented by m. To estimate the system of equations in per capita term the Seemingly Unrelated Regression method of [8] was employed. The problem of missing observation (prices) is related to the househ old who does not consume a commodity and to keep this missing observation in the analysis, average prices are used [9]. The expenditure function makes the variance and covariance matrix singular of the property of additivity is imposed. Thus, to estimate the LA/AIDS model one of the equations needed to be omitted. The expenditure equation for “other food” is omitted and by using the theoretical conditions imposed during the estimation process the coefficient for the omitted equation are derived. However, the coefficients estimated using the LA-AIDS are invariant to omitted equation.

For the LA/AIDS model elasticity derivation are extensively investigated and well documented. Following [10,11], with respect to ln(x) taking the derivative of equation 4, the expenditure elasticity can be obtained as below:

where δij is Kronecker delta that is 1 if i=j otherwise 0. Sample mean was used in this study for the point of normalization. The compensated price elasticities sij LA/ AIDS become as follows:

Own and cross price elasticities represent consumers’ response to price change. To examine the welfare effect of a price change, compensated as well as uncompensated demand price elasticities were computed. Own price elasticity of compensated demand only represents the substitution effect for a price change keeping the level of utility constant while the uncompensated demand elasticity is the summation of both the income and substitution effect. The uncompensated and compensated demand own and cross price elasticities are reported in Tables 1-3 respectively.

This study used Household Integrated Economic Survey (HIES) part of Pakistan Social and Standard Living Measurement (PSLM) for the year 2011-12. Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PSB), Islamabad conduct this survey based on household cross-section sampling and provides detailed outcome indicator on Health, Education, income & expenditures, population welfare and water supply & sanitation. Government used data collected by this survey in framing various policies. Except military restricted and protected area the PSLM survey covers all urban and rural areas in four provinces. A sample of 17,989 household has been taken from the PSLM survey data for this research. In the first stage 1743 primary sampling units were selected from urban and rural regions of Pakistan while in the second stage 15,807 households were randomly selected from these units. 16 to 12 household were selected from each primary sampling unit by using a random systematic sampling scheme [1].

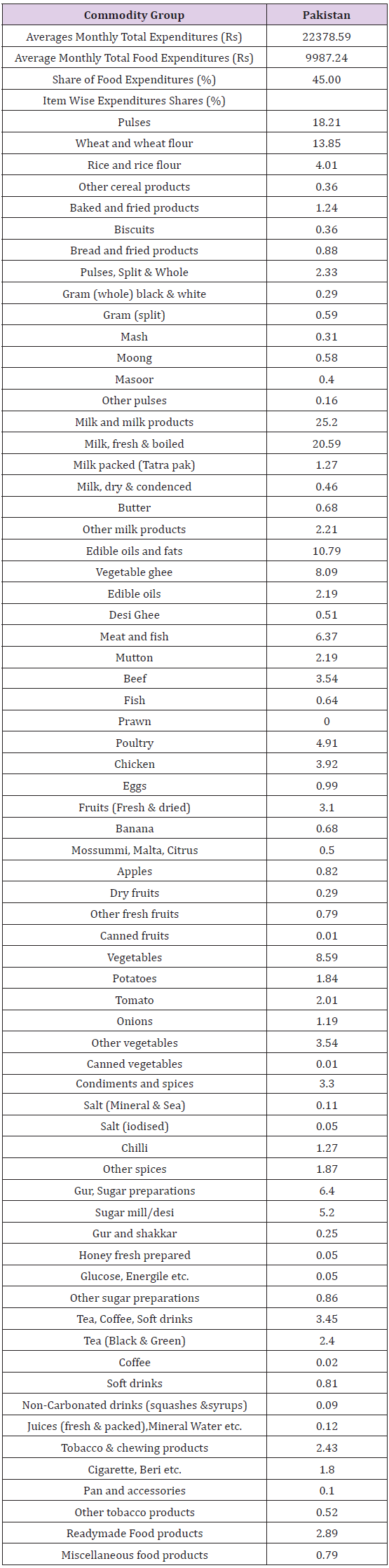

The comprehensive illustration with respect to average monthly household’s consumption expenditures on various food items during the survey period is given in Table 1 of Appendix 1. On average Pakistan household spend almost 45 % of their total expenditures on food while a typical household spends 25.2 % of their total food budget on diary, 18.02 % on pulses, 10.79 % on edible oil & fats, 6.37 % on meat, fish and poultry, 5.2 percent on sugar, 3.54 percent on vegetables and 3.1 percent on fruits (Table 1). Among cereal expenditures a large proportion is spent on wheat i.e., 13.85 % which is the main source of calories in Pakistan [2]. Government of Pakistan have heavily intervened in wheat production and marketing system because of its central role in food consumption (Darosh And Salam, 2006). Until recently, government have procured wheat at administratively set prices normally below import parity prices and subsidized consumers with the objectives of stabilizing prices in the market. Imports of government subsidized wheat have further depressed effects on wheat prices. However, to bring domestic price at par with the world wheat price the government increased wheat price. Similar results were also reported by [12-15].

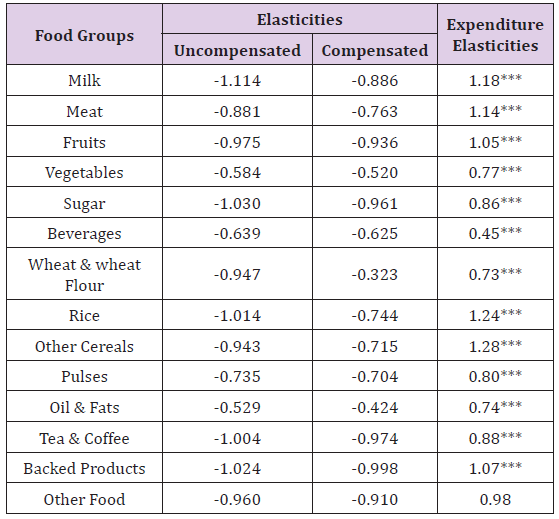

Table 1: Uncompensated/ Compensated Own Price and Expenditures Elasticities for Overall Pakistan, 2011-12.

Results of the detailed LA/AIDS estimation are omitted and only the estimated of the Uncompensated and Compensated demand and expenditures elasticities are given. However, all the results are statistically significant at 99 % level and model fit the data well.

Households in Pakistan spend their earnings on a variety of items to attain a certain level of utility. The estimated expenditures elasticities for food groups provide useful insights into the consumption level. Food being a basic necessity and an important item in terms of household expenditure, requires/consumes a significant proportion of household’s income to meet their basic life needs. Base on the estimated expenditures elasticities the food commodities can be be categorized into necessities and luxuries. Food groups having food expenditure elasticities equal to or less than “1” is considered as necessities and greater then unity for luxuries.

It is evident from the table that all the expenditures elasticities have positive signs (as per prior expectations) and significant at 99 percent suggesting that most of the food groups are recognized as essential based on their expenditure elasticities i.e. vegetables (0.77), sugar (0.86), beverages (0.45), wheat & wheat flour (0.73), pulses (0.80), oil & fats (0.74) and tea & coffee (0.88). Milk (1.18), meat (1.14), fruits (1.05), rice (1.24), other cereals (1.28) and baked products (1.07) are reported to be luxury items based on their expenditure elasticities. It can be concluded from the elasticities of the food groups will be having an increased demand when income of the consumers increase. The upward shift of food demand curve will result in higher equilibrium prices if the supply of these food groups remains the same. As the own price elasticity of all the food groups is less than unity except, meat, rice, milk, fruits, baked products and other cereals, an increase in own price due to demand curve shift will result in decreased demand by less than the proportionate change in price.

According to a downward sloping demand curve every commodity must have a negative own price elasticity sign, as per economic theory. Consumers response to change in price is represented by own/cross price elasticities. To examine the welfare effect of a price change, compensated as well as uncompensated demand price elasticities were computed. Keeping the level of utility constant compensated own price elasticity of demand represent only substitution effect for a price change. while the uncompensated elasticity of demand is the summation of both substitution and income effect. The uncompensated and compensated demand own and cross price elasticities are reported in Tables 1-3 respectively. By adjusting the consumption of the corresponding commodities, consumers were quite responsive to price change as suggested by the estimates. All the won price elasticities for food groups were of appropriate sign. The uncompensated own price elasticity for milk (1.11), sugar (1.02), rice (1.01), oil & fats (1.004) and baked products (1.02) is greater than unity which suggest that these food groups are highly responsive to own price change. The uncompensated own price elasticity of demand for the majority of the products is price inelastic ranging from 0.52 for oil & fats to 0.97 for fruits. The price elasticities for food groups like meat, vegetables, beverages, wheat & wheat flour, other cereals, pulses and other food were 0.88, 0.58, 0.63, 0.94, 0.94, 0.73 and 0.96 respectively

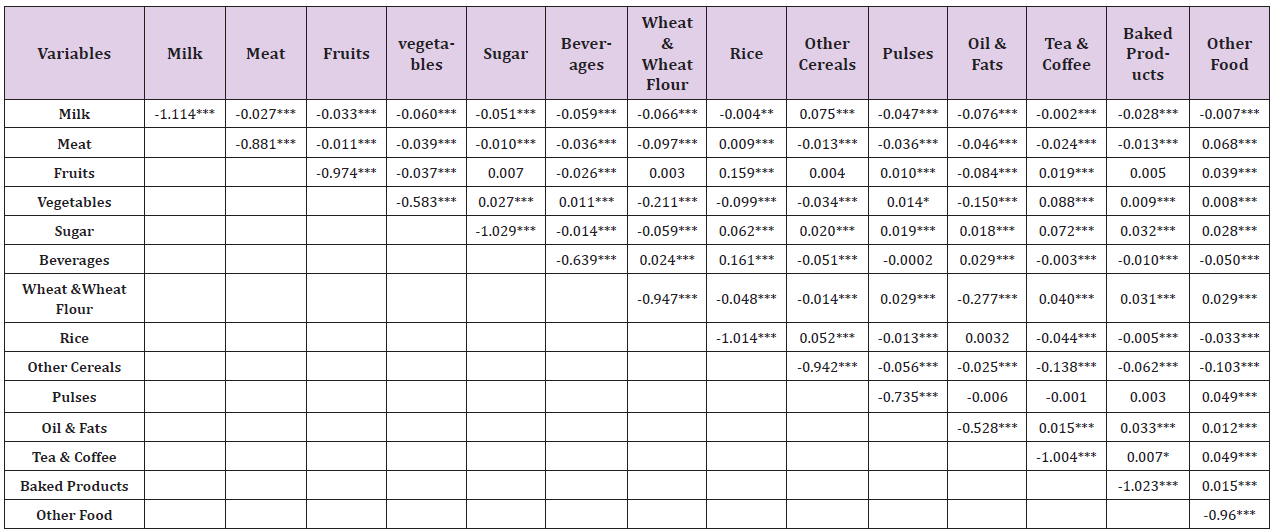

Table 2: Estimated Uncompensated (Marshallian) Own and Cross Price Elasticities for Overall Pakistan

Note. *** indicates significant at 99 %, ** significant 95 % and * significant at 90%.

Note. *** indicates significant at 99 %, ** significant 95 % and * significant at 90%.

The compensated own price elasticity of demand for all the food groups is price inelastic ranging from 0.323 for wheat & wheat flour to 0.998 for baked product. The compensated own price elasticity of demand for food groups like milk (0.886), meat (0.763), fruits (0.936), vegetables (0.520), beverages (0.624), rice (0.744), other cereals (0.715), pulses (0.704), oils & fats (0.424), tea & coffee (0.974) and baked product (0.910) were inelastic during the survey period. The estimated uncompensated own price elasticity of demand for milk, meat, fruits, vegetables, sugar, beverages, wheat & wheat flour, rice, other cereals, pulses, tea & coffee, baked products and other show that if price decrease by ten percent then for these food groups demand would increase by 11.14, 8.81, 9.75, 5.84, 10.30, 6.39, 9.47, 10.14, 9.43, 7.35, 5.29, 10.04, 10.24 and 9.60 percent respectively. Out of this total demand increase 8.86,7.63, 9.36, 5.20, 9.61, 5.25, 2.23, 7.44, 7.15, 7.04, 4.24, 9.74, 9.98 and 9.10 is the substitution effect (i.e, were purely due to price effect) as suggested by the uncompensated elasticities. The income effect because of decrease in price accounts for the remaining 2.28 (i.e, 11.17-8.86%= 2.28), 1.18, 0.39, 0.63, 0.69, 0.14, 6.24, 2.70, 2.28, 0.31, 1.05, 0.030, 0.26 and 0.50, respectively for milk, meat, fruits, vegetables, sugar, beverages, wheat & wheat flour, rice, other cereals, pulses, tea & coffee, baked products and other food increase although the absolute amount of money income remains static, is due to increase in real income. It can be concluded from the elasticities of the food groups will be having an increased demand when income of the consumers increase.

The upward shift of food demand curve will result in higher equilibrium prices if the supply of these food groups remains the same. The difference between the uncompensated and compensated own price elasticities of quantity demanded depends on the income effect for uncompensated demand. Smaller the difference between the own price uncompensated and compensated demand elasticities, less responsive will be the quantity demanded to change income (real) of consumers. In other words, the expenditures elasticities of quantity demanded for such food groups would be less elastic. As the demand for basic food items such as milk, meat, fruits, rice, other cereals, and baked products should be kept constant. Imposition of any sale tax could create huge loss in consumption for these commodities. Any increase in prices of these commodities should be backed with price subsidization policies.

Households in Pakistan spend their earnings on a variety of items to attain a certain level of utility. The estimated expenditures elasticities for food groups provide useful insights into the consumption level. It is evident from the Table 1 that all the expenditures elasticities have positive signs (as per prior expectations) and significant at 99 percent suggesting that most of the food groups are recognized as essential based on their expenditure elasticities i.e. vegetables (0.77), sugar (0.86), beverages (0.45), wheat & wheat flour (0.73), pulses (0.80), oil & fats (0.74) and tea & coffee (0.88). Milk (1.18), meat (1.14), fruits (1.05), rice (1.24), other cereals (1.28) and baked products (1.07) are reported to be luxury items based on their expenditure elasticities. It is expected that with the increase with the household’s income the demand for these food groups will also increase as suggested by their expenditure elasticities. Given the supply of these food groups are fixed and an upward shift in the demand curve will imply that the equilibrium price will also increase. Since the own price elasticity of food groups are greater than unity except milk, meat, fruits, rice, other cereals and baked products, it is anticipated that the increase in price due to shift of the demand curve will result in a decrease in quantity demanded by less than the proportionate price. The imposition of income tax on household’s personal income could reduce the consumption of these food groups. Such policies could result food security problems in low and middle income household in huge decrease in the expenditures on these commodities.

Tables 2 & 3 show the uncompensated cross price elasticities for overall Pakistan indicating substitution or complementary relations among goods and are statistically significant. When household experience a change in their relative disposable income, whether positive or negative most of them will probably first decide on the percentage of this change to be spent/cut on saving and expenditures. The household will first decide to save a specific amount of his disposable income and spent a certain amount on goods and services. Positive cross price elasticities indicate substitute goods while negative cross price elasticity means that good are gross complements. We have identified the most significant food pairs having significant cross price elasticities based on the magnitude of elasticities. Wheat & wheat flour and vegetables with oil & fats and wheat & wheat flour with vegetables were found the notable complements having cross price elasticities of 0.150, 0.277 and 0.211 respectively. While rice & fruits and rice & beverages were found substitutes with cross price elasticities of 0.159 and 0.161 respectively. The complementary or substitution relationship between all the remaining pairs of food groups their cross-price effects were observed very small. While, the compensated cross price elasticities were non-observable and have no importance for food policy (Table 2-4) shows that out of 182 uncompensated cross-price elasticities 50 are gross complements (negative) while 132 are gross substitutes (positive). Based on compensated crossprice elasticities the number of net complements equal 9 and net substitutes 173 [16-18]. We found that most of the cross-price elasticities were significant at 99 percent level of significance.

Table 4: Percentage Distribution of Monthly Consumption Expenditures Per Household on Major Food Items, 2011-12

The results of this paper has important policy implications. Prices of basic food items such as wheat & wheat flour, baked products, milk, meat, fruits, vegetables, beverages, rice, other cereals, pulses, oils & fats, tea & coffee and baked product should be kept constant. Imposition of any sale tax could create huge loss in consumption for these commodities. Any increase in prices of these commodities due to demand pull or supply push inflations should be backed with price subsidization policies/programs of rise in the household’s income. The uncompensated own price elasticity of demand for milk, meat, fruits, rice, other cereals and backed products are more elastic to food expenditures and can be categorized as luxury goods. As the demand for milk, meat, fruits, rice, other cereals and backed products are more elastic to total food expenditures (income). Imposition of any income tax on household personnel income could reduce their consumption of these food groups. Such policies could result food security problems for low & middle income households in Pakistan.