Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Rodriguez Rivera Sofia Lucila,1, Perez Ramirez1 and Jose Mariel2

Received: May 25, 2018; Published: May 31, 2018

*Corresponding author: Sofia Lucila Rodriguez-Rivera, Department of Pediatric Neurology, Centro Medico Nacional La Raza; Calzada Vallejo S/N, Col. La Raza, Delegacion Azcapotzalco, Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2018.05.001153

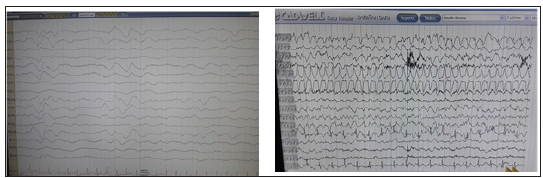

The importance of intermittent delta activity and periodic patterns in the electroencephalogram has intrigued neurophysiologists for decades. The clinical interpretations varied from nonspecific to suggested structural metabolic behavior, infectious and even epilepsy [1]. The most frequent clinical features were determined by clinical history of children with intermittent rhythmic delta activity and periodic patterns (January 2013-June 2017). Total 16 patients, Female 9 (56%). Periodic patterns: 25% (n = 4) PLEDs, 13% (n = 2) BiPLEDs and 6% (n = 1) GPEDs. Intermittent rhythmic delta activity: 50% (n = 8) FIRDAs and 6% (n = 1) OIRDAs. The most frequent causes of PLEDs were infectious and tumoral in 12.5% (n = 2) respectively. Tumor causes were the most frequent cause of FIRDAs 31% (n = 5), then neuroinfection12.5% (n = 2) and vascular 6% (n = 1). The most frequent periodic pattern was PLEDs and the most frequent intermittent rhythmic delta activity was FIRDAs, with more common etiologies tumor and neuroinfection, which is similar to the international literature [2,3].

Keywords: Intermittent rhythmic delta activity, Periodic patterns

The importance of intermittent delta activity and periodic patterns in the electroencephalogram has intrigued neurophysiologists for decades. Clinical interpretations varied from nonspecific to suggested structural, infectious, metabolic behavior and even epilepsy [1,4-7].

The patients were interviewed, the purpose of the study was explained to them and they signed an informed consent letter. The most frequent clinical features were determined by clinical history and neurological examination of infant patients with intermittent rhythmic delta activity and periodic patterns in the electroencephalogram, in Hospital Infantil de México “Federico Gómez”, Mexico City, in the period of January 2013 to June 2017. The results obtained were compared with that reported by the World Literature.

During the period from January 2013 to June 2017, a total of 16 patients with a diagnosis of intermittent rhythmic delta activity and periodic electroencephalogram patterns were reported. Predomi nance of female gender 9 patients (56%). Of the periodic patterns, 25% (n = 4) corresponded to PLEDs, 13% (n = 2) BiPLEDs and 6% (n = 1) GPEDs. Of the intermittent rhythmic delta activity, 50% (n = 8) corresponded to FIRDAs and 6% (n = 1) OIRDAs. Infectious and tumoral causes were the most frequent cause of PLEDs, presenting 12.5% (n = 2) respectively. Tumor causes were the most frequent cause of FIRDAs, presenting in 31% (n = 5), followed by neuroinfection in 12.5% (n = 2) and vascular in 6% (n = 1).

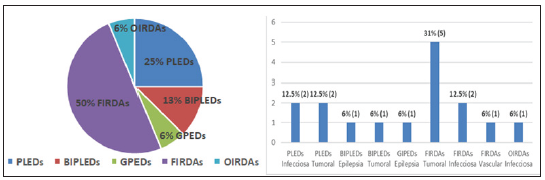

The most frequent periodic pattern was PLEDs and the most frequent intermittent rhythmic delta activity was FIRDAs, with more common etiologies tumor and neuroinfection, which is similar to the international literature [2,3,8-10] (Figures 1& 2).

Figure 1: Frequency and etiology in intermittent rhythmic delta activity and periodic patterns in the electroencephalogram (A and B).

Figure 2: Intermittent rhythmic delta activity and periodic patterns in the electroencephalogram (A and B).