Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Cheptum Joyce*, Omoni Grace and Mirie Waithira

Received: March 09, 2018; Published: April 06, 2018

*Corresponding author: Joyce Cheptum, School of Nursing Sciences, University of Nairobi, Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2018.03.000929

Background: Death of a pregnant woman is very devastating for the family and the community at large. Most of the causes of death are preventable through various strategies such as birth preparedness. When there is preparation early in advance, delays which can lead to morbidities or mortalities can be averted. Despite the strategy being in place for over 20 years, there are factors which affect its practice. This study sought to establish the factors affecting birth preparedness among pregnant women attending public antenatal clinics in Maori County.

Methods: This was a descriptive cross-sectional study employing quantitative method though use of interviewer-administered questionnaire and qualitative method using focus group discussion. The study was carried out among pregnant women attending public ANC clinics in Migori County. Data analyzed using Strata version llsoftware.

Results: The factors which affected birth preparedness were marital status (p=0.004), residence (p<0.001), maternal occupation (p=0.01) and the partner's level of education (p=0.001). Also, the type of health facility attended by the respondent was significantly associated with birth preparedness (p<0.001).

Conclusion: There are socio-demographic, economic and socio-cultural factors affecting birth preparedness.

Keywords: Birth Preparedness; Antenatal Care; Pregnant Women; Factors; Pregnancy

Abbreviations: ANC: Antenatal Care; BP: Birth Preparedness; FGD: Focus Group Discussion; MNH: Maternal Neonatal Health

Birth preparedness and complication readiness (BP/CR) matrix developed in 2004 by the maternal and neonatal health program aims at preventing obstetric delays thus reducing maternal morbidity and mortality occurring from preventable causes. It points out the roles of policy makers, health providers, families and the women in facilitating skilled birth attendance [1]. The birth preparedness matrix comprises of having basic knowledge on danger signs of pregnancy; identifying a place of delivery early; saving finances for transport or labor and delivery; making transport arrangements in case of an emergency or during labor; obtaining basic supplies for delivery such as baby clothes, identifying a birth companion and planning for the family while away to deliver or in case of emergencies. Birth preparedness (BP) is hindered by several factors which include socio-demographic, socio-cultural, economic and political. All these contribute positively or negatively in enhancing the practice of birth preparedness.

Socio-demographic factors can significantly be associated with birth preparedness and utilization of skilled birth attendance Kuganab-Lem Several studies have reported low level of education, occupation, and distance to the health facility, services offered at the health facility and staffing as factors which affect birth preparedness eventually leading to unskilled birth attendance [2,3]. Knowledge of danger signs of obstetric emergencies and appreciation of the need for rapid and appropriate response when emergencies occur may reduce delay in decision making and in reaching health facilities [4]. Planning to save money for delivery has been associated with skilled birth attendance [5]. A study carried out in Edo, Nigeria established that education level and occupation were determinants of birth preparedness [6].

Older age, maternal government employment and higher social class was significantly associated with birth preparedness [7]. Age at first birth and the number of live births were also associated with utilization of skilled birth attendance and birth preparedness [8]. The younger the woman at birth, the higher the risks of complications, therefore this is likely to increase their possibility of utilization of skilled birth attendance. A woman who has had poor obstetric outcomes is more likely to utilize skilled care as compared to one who may have had uneventful pregnancies. Sociocultural barriers have been identified to contribute to delay in seeking health care owing to various beliefs [8]. These factors serve as a limitation to adoption of good practices such as health facility delivery, hygienic cord care and maternal and infant nutrition during pregnancy and post-delivery.

The socio-cultural barriers potentially increase the risk of obstetric and newborn complications. BP prevents delays in decision making especially in societies where decision-making does not entirely depend on the woman [9]. Study in Nepal established that women did not seek health care services at birth even if the health facility was near because of the cultural practice of isolating a woman during delivery and a few days after birth [5]. Obstetric factors can influence the knowledge and practice of women on birth preparedness. A Nigerian study established that a woman's gravidity, knowledge on ANC attendance, number of ANC visits and outcome of previous deliveries were significantly associated with birth preparedness [10].

A study in Ethiopia documented that history of a stillbirth and attendance of ANC in the preceding pregnancy was significantly associated with birth preparedness and complication readiness [10]. In addition, the study also recognized that male involvement in ANC led to birth preparedness [11]. Parity is also a factor contributing to BP according to a study in Nigeria [12]. And also in Goba district, Ethiopia [13]. Elderly prim gravid as have a risk of developing pregnancy and childbirth complications due to diseases such as diabetes mellitus and pre-ecliptic toxemia thus are more likely to make preparations for delivery. A study [11] Suggested that women in the age group of >35 years should be informed of their pregnancy expectations and outcomes.

This was a facility based descriptive cross-sectional study which utilized quantitative and qualitative methods to assess the factors affecting birth preparedness messages among pregnant women attending antenatal clinics in Maori County. The study was carried out in four selected public health facilities. The facilities were stratified as high and low volume. Simple random sampling was done to select the facilities for study. These facilities were Maori County hospital, Isibania sub-County hospital, Godwit health centre and Aerobe dispensary and they were high volume facilities. A sample size of 389 pregnant women attending antenatal care clinics (ANC) were randomly selected to participate in the study. In the facilities of study, one focus group discussion (FGD) was conducted among pregnant women who were randomly selected irrespective of their age, parity or previous obstetric outcome.

Quantitative data was collected through an interviewer- administered questionnaire while qualitative data was collected using FGD. Research assistants who were trained helped in collecting quantitative data while the principal researcher conducted the FGDs. The clients who met the inclusion criteria were interviewed after receiving ANC services. For quantitative data, entry and cleaning was done to check for data quality and detect any errors and omissions. Descriptive statistics were presented using figures and tables. For qualitative data, transcription was done, the emerging themes were organized and thematic analysis was done. This was reported in form of narration. Ethical review was sought from University of Nairobi/ Kenyatta National Hospital Ethics review committee.

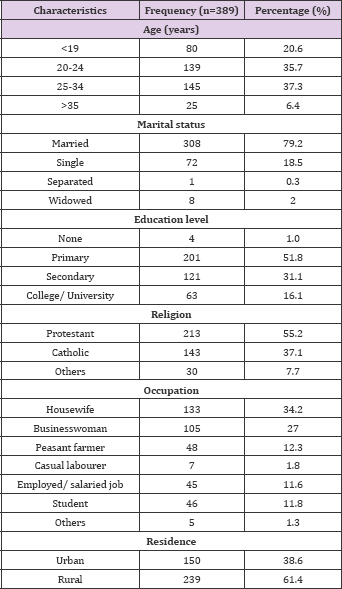

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents.

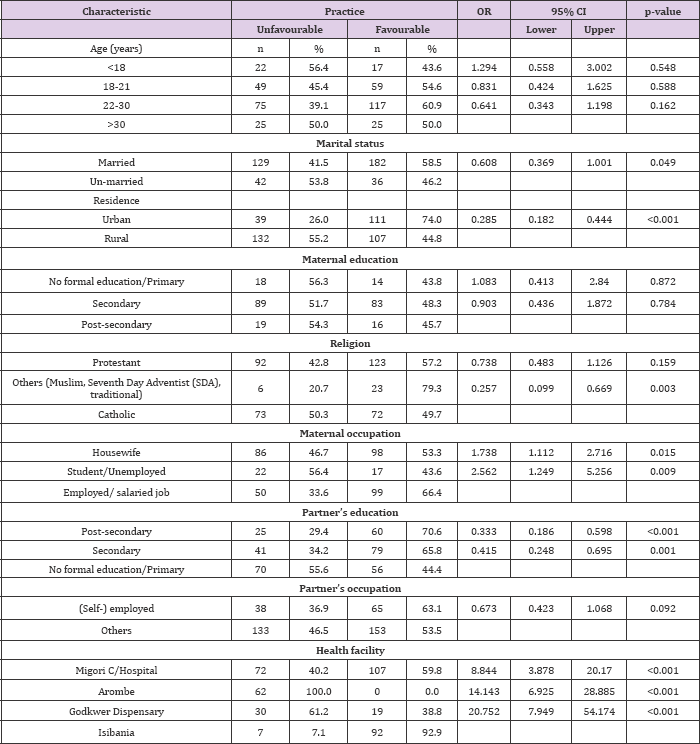

Majority of the participants were aged between 20 -28 years. The teenagers contributed to 20.6% (n=80) of the participants. Majority of the respondents (79.2%) were married. Only 16.7% of the respondents had attained post-secondary education those who had primary level of education were 51.7%. Protestant was the predominant religion among the study participants (55.2%). Most of the respondents were housewives (34.2%) and businesswomen (27%) while 11.8% of them were students. Most of them were rural residents (61.5%). Table 1 illustrates the demographic findings. Regression analysis was done to assess factors associated with practices on BP. Being married was found to be associated with engaging in favorable practices of birth preparedness (OR 0.608 (95% CI 0.369 - 1.001), p=0.049). Urban residence was associated with favorable practices of birth preparedness (OR 0.285 (95% CI 0.182 - 0.444, p<0.001). Also maternal occupation, partner's education level, religion and the type of health facility were other factors significantly associated with favorable practices of birth preparedness (Table 2).

Table 2: Factors associated with practices on BP.

The respondents had various beliefs about birth preparedness. Some felt that it was wrong to prepare for childbirth since the baby might die while others felt that having ready items before the baby is born would bring a bad omen. The FGD responses regarding beliefs, taboos and values about birth preparedness were as follows:

a. "I will not prepare for the baby because the baby will die" (Respondent 7, FGD 2)

b. "Even if my husband will buy the baby's clothes, he will leave them in the shop until when the baby is born. The clothes can't be brought to the house because it is bad in our culture". (Respondent 1, FGD 3)

c. "We don’t prepare for child birth because it is against our culture". (Respondent 2, FGD 3)

About preparation for the place of delivery, the respondents said that they did not plan for a specific hospital since it would dictated by where they would when labour begins. These are the responses from the FGD about their plan for birth preparation.

a. "I will not buy clothes because I don’t know if am carrying a baby or not. I will wait until the baby has been born then that is the time to buy" (Respondent 7, FGD 3)

b. "I don't know what am carrying in my uterus, so I will not prepare until when the baby is born" (Respondent 2, FGD 2)

c. "I will not decide on where to deliver until the day when labour begins" (Respondent 4, FGD 3)

d. 'All I will do to prepare is to have money ready. My husband is responsible for looking for the money and then I will send him to buy the clothes when the baby is born". (Respondent 1, FGD 1)

e. "Within the health facility, there are shops that I can buy the clothes after birth. I can’t buy the clothes now". (Respondent 8, FGD 4)

f. "I don't know where I will deliver because I don’t know where I will be when labour begins". (Respondent 6, FGD 2)

g. "I don't have a ready bag for delivery. When labour begins, I will just go to the hospital with a leso for holding the baby". (Respondent 5, FGD 1)

The perception of birth preparedness varied among the respondents. Some said it was good since all that is needed would be available while others felt that it would make the baby to die if one prepared for birth as shared in the responses below.

a. "Preparation is good because you will have everything" (Respondent 3, FGD 4)

b. "Preparation can make the baby to die, therefore it is wrong to do it" (Respondent 7, FGD 2)

c. "It is good if you have money for boda and for buying baby clothes". (Respondent 1, FGD 2)

d. "If I buy the baby’s clothes and the baby dies, what will I do with the clothes?" (Respondent 8, FGD 1)

Age is a critical variable in reproductive health since women who are too young or too old when giving birth stand a higher risk of complications as compared to those who are within the prime reproductive age bracket. This is the age where most women are physically and emotionally mature and ready to settle down in marriage. Most of the respondents were within the prime reproductive age bracket. These study findings are supported by results from an Ethiopian study assessing the practices and factors associated with birth preparedness [13] which established that most of the respondents were in the same age range. However, in this study, there were a number of teenage mothers. Teenage pregnancy increases the risk of pregnancy and childbirth-related complications owing to physical immaturity coupled with other social factors such as poverty. Based on this, the woman may not receive the appropriate support she needs through the pregnancy.

At this age, most of the girls are not yet socially and economically independent, still schooling and are still reliant on their parents and guardians. The study findings agree with the results of the Kenya demographic health survey which established that almost a quarter of all the pregnancies happened among the teenagers [14]. Education level has been associated with birth preparedness [10]. The women who had higher level of formal education were more likely to be prepared as compared to those who had lower level of formal education. The findings of this study are in agreement with other studies which established a relationship of birth preparedness and education level [15]. In the study, most of the respondents had only completed primary level of education while others did not complete primary level of education. This could be attributed to early age at childbirth which makes the girls to drop out of school thus unable to continue with their education.

The findings of this study are in agreement with Ethiopian studies [11,13]. The results of this study indicate that there is a high possibility of school dropout since most of the respondents had only attained primary level of education and this may affect the literacy levels. Education empowers women to obtain information that can help them to make decisions independently [16]. Despite the return -to- school policy by the ministry of education in Kenya, which allows the girls to go back to school after childbirth, some of them may not manage owing to lack of social and financial support for them and their children. Higher level of education has been associated with birth preparedness. In the study, the women who had higher level of education were more birth prepared as compared to those who had lower level of education.

These findings are in agreement with an Ethiopian study which indicated that women with secondary level and above showed more preparedness [17]. Low level of education has been associated with low socio-economic status indicating that poverty levels are likely to increase [16]. High poverty level is likely to affect birth preparation since part of the preparation includes setting aside finances in case of emergency. This may be difficult in a situation where meeting the basic needs such as food is at stake. Occupation is another factor that affects birth preparedness. In the study, majority of the respondents were housewives, peasant farmers or casual laborers.

These occupations are associated with low income which is likely to affect their economic independence. When women are economically empowered, they are likely to be more birth prepared since they may not need economic provision by their partners. When preparing for birth, having finances for transport and other utilities is vital to ensure prompt arrival in the health facility in case of labour or an emergency. One of the reasons why delay occurs in seeking care is lack of finances for transport or other services [18]. Which make it difficult for the woman to access the health facility? Most of the partners of the respondents had complete primary level of education and most of them worked as businessmen, casual labourers or peasant farmers indicating that they were likely to have low wages. In the County, the people living on less than one dollar per day are 43.1%.

Low wages are associated with high poverty levels and economic instability since these people will be struggling to meet the basic needs and may not be able to meet other demands such as preparing for birth [10]. In this study, the partner's occupation was not associated with the partner’s awareness of birth preparedness. The findings contrast with those established by a study in Jimma zone, South west of Ethiopia which showed that the husband's occupation was significantly associated with knowledge of birth preparedness [19]. Involvement of a male partner during antenatal care follow up leads to better birth preparedness Raatikainen, Heiskanen & Heinonen. Marriage has been associated with positive pregnancy and child outcome [20]. While unmarried status is associated with social disadvantage and poor obstetric outcomes [21,22].

Being married enhances social and economic support during pregnancy and childbirth through preparation and decisionmaking. Most of the respondents in this study were married. Marital status was not significantly associated with knowledge of birth preparedness in this study. These findings contrast those of a study conducted in Edo estate, Nigeria which found significance of marital status in birth preparedness [5]. Marriage enables individuals to share decisions thus are able to offer support to each other. Pregnancies that occur during teenage are categorized as adolescent pregnancies. These pregnancies face a lot of risk both to the mother and her unborn child [23].Most of the respondents in this study had their first birth during the teenage period. The early age at birth could be attributed to low level of education and low socio-economic status as established in the study

Several studies have linked teenage pregnancies to lack of knowledge, peer pressure, lack of utilization of contraceptives and cultural practices such as forced marriages [18]. Religious practices have been shown to affect birth preparedness due to different religious practices prohibiting or enhancing birth preparation. Most of the respondents were Protestants. Religions other than protestant and Catholic were significantly associated with birth preparedness. These findings are in agreement with an Ethiopian study which established that Muslim religion was associated with birth preparedness [24,25]. However, a study assessing the factors affecting birth preparedness in Ethiopia and West Bengal which revealed no association of religion and birth preparedness [26,27]. Practices carried out in some religions likely to affect birth preparedness positively or negatively.

Some religions believe in not seeking formal health care or disapprove some health care services such as blood transfusion thus this will jeopardize health of the individual. Other religions encourage their clients to utilize health care services thus this offers promotion of the services. Majority of the Kenyan population reside in the rural areas. In this study, most of the respondents resided in the rural areas. The urban residence was associated with birth preparedness. These findings are in agreement with other studies in Ethiopia [28-30]. As compared to those residing in the urban setting, those in the rural area may not freely access some amenities because of their unavailability thus, they may be required to seek the services in the urban areas. Parity is a predictor of birth preparedness and this may be due to previous experience for those who have given birth before or the anticipation for childbirth for the first time mothers.

The respondent’s parity was significantly associated with having heard about birth preparedness. These findings are in agreement with findings of Ethiopian and Indian studies which established that parity was a predictor of birth preparedness [28]. The findings of this study are supported by those of several studies which showed that an increase in parity has been associated with birth preparedness [31]. When a woman gives birth once, they tend to gain experience in the subsequent pregnancies thus are more likely to be ready. A study to assess the impact of mother-in- law’s parity on birth preparedness had contrary findings where it established that there was no significant association [32]. Gestation of pregnancy was significantly associated with birth preparedness in this study. This could be attributed to the fact that most women tend to start preparations for delivery late in pregnancy.

The findings are in agreement with those of a study conducted in Western Kenya which established that women tend to book antenatal care (ANC) late thus may not have adequate time for preparations for childbirth [31]. In most cases, women have a tendency of beginning ANC during the second or third trimester thus may not achieve the four-world health organization (WHO) recommended ANC visits. This implies that they may not receive adequate health education messages which will enable them to be ready for labour and delivery. In this study, cultural taboos and beliefs hindered birth preparation whereby the society believed that the baby must be born first so that preparation such as clothes could be bought. These findings relate to those of a study in Lurambi, Kakamega in western Kenya [32]. This could be ascribed to the fact that the region where this study was done bordered the western region thus there was a possibility that these communities had some cultural taboos and beliefs in common.

One of the beliefs for not making childbirth preparations in this study was that the child could die at birth if preparations were made prior. No woman would wish to lose her child at birth; instead, they would prefer to adhere to the cultural beliefs and taboos. In a Tanzanian community, there is stigmatization of young girls who get pregnant before marriage [33]. Cultural and traditional practices such as use of herbs during labour hinder health facility delivery [34]. In Nepal, owing to the cultural practices and traditional beliefs, many women delivered outside the health [35].

One of the key components of birth preparedness is delivery assisted by a skilled birth attendant. When women opt to deliver outside the health facilities where unskilled attendants assist them, it could mean they are inadequately prepared for birth [26,17,36]. In most societies, the place of delivery is a decision [37-40]. Mostly made by the family members and not the woman in the community of study [41] men were mainly the decision makers in the home since it is a patriarchal society [42]. Consultation between the woman and her partner regarding birth preparation significantly affects seeking of skilled birth attendance [18].

The factors that affect birth preparedness range from individual, partner and community. They include socio-demographic, economic, socio-cultural and health facility factors.