Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Mayumi Uno*

Received: January 06, 2018; Published: January 17, 2018

*Corresponding author: Mayumi Uno, Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, Yamadaoka 1-7, Suita, Osaka, 565-0871, Japan

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2018.02.000666

Aims and Objective: To determine nurses’ and patients’ perceptions regarding nurse-patient conflicts.

Background: Nurse-patient conflicts, and both parties’ responses to them, are known to influence patients’ perceptions of the quality of nursing care. However, there remains a need to better understand and conceptually interpret both parties’ perceptions, which this study aimed to fulfill.

Design: A qualitative study aiming to create a conceptual model.

Method: Participants were nurses attending nurse-manager training courses and phone counselors who handled calls from patients seeking advice. Descriptive surveys were distributed to 320 nurses in August and November 2012, January 2013, and June 2014. We further conducted 8 interviews with phone counselors in December 2013 and January-February 2014, which were also supplemented with existing data from a previous study.

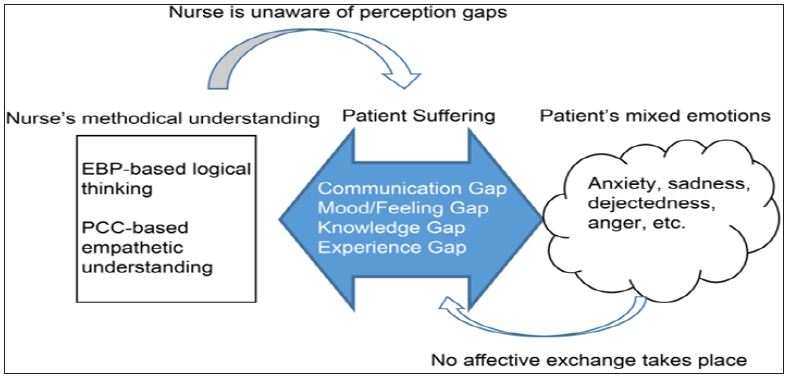

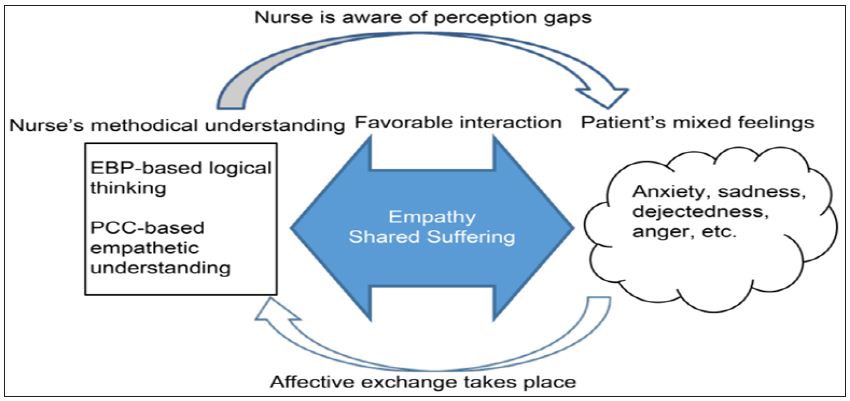

Result: Two conceptual models were formed, depending on whether nurses demonstrated awareness of perception gaps within nursepatient conflicts. When nurses were unaware of such gaps, patients experienced “suffering” because no compensatory interaction occurred. However, when nurses were aware of the gaps, a favorable interaction occurred because they established an empathetic connection with patients. Perception gaps could be categorized as communication, mood, knowledge, and experience gaps.

Conclusion: Nurses should be aware of nurse-patient perception gaps arising from conflicts with patients. By establishing a connection with patients through recognition of these perception gaps, nurses can leverage their empathetic understanding of patients to produce positive interactions. These results may contribute to improvement in patient perceptions of nursing care quality.

Relevance to Clinical Practice: By recognizing the gaps in perceptions between themselves and patients, nurses can better understand patients’ emotions and nurture beneficial interactions. These, in turn, may contribute to improving the quality of nursing care.

What Does This Paper Contribute To The Wider Global Clinical Community?

A. This study offers suggestions on the competencies nurses must have to transform nurse-patient conflicts into productive experiences for both parties.

B. We offer a conceptual framework for understanding nurse-patient conflict that is based on nurses’ awareness of perception gaps between themselves and patients.

Keywords: Quality of Nursing; Nurse-Patient Relationship; Conflict; Perception Gaps; Suffering; Empathy; Qualitative Research

Abbreviations: PCC: Patient-Centered Care; EBP: Evidence-Based Practice; SD: Standard Deviation; EI: Emotional Intelligence

With the increasing complexity of advanced medical care services, health care practitioners have entered a period wherein greater emphasis is being placed on the monetary value of health care, and the quality of medical care is based on patient understanding and satisfaction. There is a belief that patient satisfaction should be assessed as part of a broader assessment of care quality-which includes the quality of medical and social services-rather than being independently considered [1]. Nevertheless, numerous studies of nursing care quality have focused on patient perceptions, starting with a well-known study by Risser and NL [2]; since then, emphasis has been placed on research from the perspective of patient satisfaction. Lin and CC [3], for example, reported that patient satisfaction has been strongly advocated by nursing professionals as an important indicator of health care quality and efficiency.

High quality nursing care involves establishing trusting relationships with patients. According to Watson [4], such relationships are dependent on the nurse’s ability to be authentic and open. Regarding the importance of nurse-patient encounters, Peplau and HE [4] has argued that the initial encounter is of particular moral significance because the way in which nurses meet patients communicates the extent of their understanding of patients’ vulnerability. Bégat et al. [6] reported that the organization of care has, over time, changed from target- to patient-centered care (PCC)-namely, more reliant on the establishment of a closer relationship between patient and nurse. Empathy has long been considered an important concept in the nurse-patient relationship.

Before the use of empathy as a technical term, Florence Nightingale referred to the concept of “sympathy” (which bears strong resemblance to the current concept of empathy) when speaking of the nurse-patient relationship. She said that one quality of a nurse was that they “must always be kind and sympathetic, but never emotional” [7]. Sympathy has been recognized as something that aids the therapeutic process in the nurse-patient relationship [8,9]. Henderson [10] noted that “getting inside his/her skin” (i.e., empathy) is a way to understand a patient, while Erikson [11] considered empathy to involve “feeling concern for suffering”-a nurse must acknowledge a patient’s suffering to make the patient feel respected as a person.

Specifically, to alleviate a patient’s suffering, nurses must determine each patient’s desires, trust, hope, powerlessness, guilt, and shame, [12] and a nurse should understand each patient’s unique experience of their disease, knowledge, and feelings [11]. Such a nurse-patient relationship is considered the foundation of the therapeutic relationship. Van der Cignel [13] considered compassion as another important concept in the nurse-patient relationship, believing that compassion is an answer to suffering and lies at the heart of care; indeed, it is equivalent to good quality care in health care today. The importance of compassion in the nurse-patient relationship is not a new phenomenon; it has played a part in nursing spanning from Nightingale to dozens of modern theories [14]. Kindness, concern, sensitivity, caring, compassion, and empathy are known as the most valued activities of nurses [15].

The concept of nursing care quality is both universal and everchanging. For instance, PCC in the nurse-patient relationship has been considered the foundation of nursing care, and concepts like sympathy and empathy have received universal attention. Nurses’ therapeutic drive can be activated when delivering PCC by developing a therapeutic [16,17,18]. According to Siadani [19], PCC is linked to excellence and improves the quality of patient care. PCC has been defined in various ways. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [20] emphasizes that PCC enhances the quality of the interaction between patients and medical care providers, which empowers patients. As for how the concept has changed, around the year 2000, “high-quality nursing care” came to be based on the use of evidence-based practice (EBP), which has since defined the perspective nurses should take when engaging in professional behavior [21-24].

Notably, EBP, according to Sackett et al. [23], considers the weight of patient opinions and professional knowledge as a basis for professional behavior and decision-making in practice alongside scientific evidence. According to Burman et al. [25], patient preferences are a cornerstone of EBP, and the integration of EBP and PCC is integral to successfully engaging patients in health care. He emphasizes that we must develop strong organizational cultures with a commitment to empowering nurses and other clinicians to provide interdisciplinary interventions, PCC, and EBP. However, it is difficult to consistently maintain good nurse-patient relationships and, occasionally, this affects patients’ perceptions of nursing care quality

Bissell [26] suggested that cultivating a mutual relationship and demarcating understanding is necessary for patients and care providers to maintain a good relationship. They observed that when an interpersonal relationship cannot be maintained without difficulty, conflicts arise. Robbins [27] defined a conflict as the process that begins when someone perceives that another person is negatively influencing or trying to negatively influence something that is important to him or her. The commonalities of this definition with those of various other researchers are that conflict is a “confrontation” or “discordance,” as well as “a type of interaction.” Researchers have pointed out that thinking about conflict has changed over time. Traditionally, conflict was regarded as something to avoid. This gave way to a human relations viewpoint indicating that conflict inevitably occurs within every group.

Most recently, there is the inter actionist view-namely, that some conflict is necessary for groups to function effectively. According to Marquis and Huston [28], conflict arises from differences in perceptions, values, expectations, and backgrounds. Studies on conflict based on the human relations theory over the last decade have focused on special patient situations and difficult patients [29], acute psychiatric wards [30], and the tendency for nurses to cope with conflict by choosing strategies that lead to resolution through discussion [31]. Regarding conflicts arising between nurses and patients, Uno. [32] investigated ideal nurse involvement with patients and reported that intimately sharing even slight changes in patients’ feelings led to improvements in nursing care quality. Furthermore, Uno [33] emphasized that patients expect that during a conflict, others will try to be empathetic toward them; such empathy grants nurses an understanding of the patients’ feelings.

Overall, emotions are not specifically human characteristics, but reactions to events occurring in one’s environment [34], and their impact on daily life is considerable. Nurses, in reacting to patients, do generally understand that their emotions are inseparable aspects of their own daily lives- nevertheless, it is undeniable that conflicts arise in their interactions because of the norm in nursing practice that nurses must suppress their emotions [33]. In the present study, we sought to investigate the perceptions of both parties involved in nurse-patient conflicts. In other words, we sought a conceptualization of nurse-patient conflict that is based on a qualitative understanding of both nurse and patient perspectives, rather than on nurses’ perceptions alone.

The purpose of this study was to construct a conceptual model of nurse-patient conflicts by exploring both sides of the nursepatient relationship.

a. Conflict: In this study, conflict does not refer to evidential conflicts (e.g., medical disputes), but rather to nurse-patient mood discrepancies and emotions. Telephone counselors: It is non-medical staff of counselors belonging to the NPO Corporation. The counselor will consult the patient with common sense. The background of the telephone counselor has experience of himself or herself as a patient. From the experience of the patient, they can understand dissatisfaction etc.

Descriptive surveys were distributed to 320 nurses who attended nurse-manager training courses sponsored by a nursing profession association in Osaka Prefecture, Japan. Eligible participants had managerial-level nursing experience and were able to verbalize that experience. We considered being an attendee of these national courses as evidence of eligibility to participate in this study, given that certain established attendance criteria must be met. Because it would have been problematic to obtain patient data by directly interviewing patients for the study, we interviewed 8 phone counselors instead. These phone counselors worked for a non-profit organization comprising people outside of the medical profession in Osaka Prefecture, who provided sympathetic advice as fellow residents to patients who were having problems with communicating their moods, feelings, and other issues to their medical care providers. The eligibility criteria for the phone counselors were that they had a certain amount of training and experience and were able to accurately pick up on patients’ moods and feelings, which the patients were not able to communicate to the nurses themselves.

Additionally, we added 40 cases of phone counseling descriptive data (referred to hereafter as “existing data”) from the same telephone consultants to the study data, which we judged as equivalent to this study’s interviews; a summary of the contents can be found in Yamaguchi [35]. These were recordings of consultations about aspects of care that patients could not voice directly to the nurses by phone, such as unclear instructions by nurses or family considerations. Patients in these recordings said that they had not been able to voice these concerns in a systematic way while in the hospital because nurses gave priority to talking about resuscitation orders and their emotions regarding the treatment. Note that these additional phone counseling data were not limited to the counselors who participated in this study; as such, they may reflect the voices of typical Japanese patients.

For this study, we adopted the four stages of the conflict process outlined by Robbins [27]. We verified the consistency of the original texts with the stages outlined below, while also adding a section on personal characteristics. To ensure the content validity of these items, we conducted a trial with 5 graduate students who had 7 or more years of clinical experience as nurses. They verified that the content of the items was appropriate.

Stage 1: Potential for Confrontation (underlying factors that may have caused the conflict)

Stage 2: Perception and Personalization (scenario in which the conflict arose)

Stage 3: Behavior (nurse’s response to the conflict)

Stage 4: Results (nurse-patient relationship after the response to the conflict)

For the descriptive survey for nurses, we instructed the nurses to recall a nurse-patient conflict. As for personal characteristics, we asked for their age and years of nursing experience at the time the conflict occurred. For the phone counselor interviews, we asked them to recall the content of conversations related to nurse-patient conflicts. We also verified that the existing data could be organized in the same way. As for personal characteristics, we referenced the age of the patient who called and the phone counselor’s phone consulting history.

For the nurse data, descriptive surveys were distributed to the 320 nurses in August and November 2012, January 2013, and June 2014. After explaining the study purpose to people in charge of the training courses and obtaining their permission, we provided verbal and written explanations to all course attendees. The survey was anonymous. We placed a collection box at the training site for 2 weeks to collect the surveys. We considered consent to participate in the study as returning the completed survey. Phone counselor data were obtained via interviews with the 8 counselors in December 2013, and January and February 2014. This was supplemented with the existing data from Yamaguchi, which was collected in 2010-2011. Because it was not feasible to collect data on the same events from both the perspectives of nurses and patients, we stipulated that responses should relate to “a conflict that had occurred between a nurse and patient during the patient’s stay in the medical facility.” As the resulting data would describe similar events, we considered the nurse and patient data to be relatively equivalent.

We explained to all eligible participants that the data obtained in this study would not be used to identify any individuals or used outside of this study; further, it would be strictly managed and destroyed upon completion of the study. Furthermore, we explained to the nurses that participation was voluntary, refusal to participate would not be disadvantageous to them in any way, participation had no relationship with their course evaluation, and we would consider their submission of the survey form as their having consented to participate. By contrast, in our explanation to the phone counselors, we assured them that participation in the interview was voluntary, had no relationship with their company performance evaluation, and they could rescind their consent to participate at any time. We obtained permission to use the existing data from the copyright holders. This study was conducted under the approval of our institution’s research ethics committee.

We examined the characteristics of the conflict by carefully reading and then qualitatively and recursively analyzing the descriptive data from the nurses and phone counselors (including the existing data). We used the framework of Polit and Beck [36] for this analysis. Next, we examined what aspects of the nurse-patient conflicts led to a worsening or an improvement in that relationship. The analysis results were carefully reviewed by two university faculty members specializing in qualitative research to ensure the credibility and validity of the analysis.

Nurses’ mean (standard deviation [SD]) age was 41.4 (3.38) years, while their mean years of experience was 20.5 (4.28). By contrast, the mean years of experience of phone counselors was 6.7 (4.12). The interviews with the counselors each lasted for about 50 minutes. The ages of patients calling for advice ranged from 40 to 80 years.

Of the 72 surveys returned by the nurses, a total of 66 were relevant to the study objectives and were included in the analysis. All phone counselor interviews were transcribed, providing data on 32 different topics of conversation. Coupled with the additional 40 conversations from the existing data, the phone counselor data comprised 72 conversations; however, only 62 conversations were relevant to the study’s objectives and were used for the analysis. We broadly categorized the nurse-patient conflicts into two conceptual models according to whether or not the nurse demonstrated awareness of the perception gaps caused by this conflict. When nurses failed to recognize perception gaps, patients experienced suffering because no compensatory interaction occurred between them (e.g., nurses recognizing and empathizing with suffering of patients) (Figure 1). When nurses recognized that there were such gaps, a favorable interaction occurred because nurses compensated with, for example, an empathetic connection (Figure 2). Furthermore, depending on the conflict, we classified perception gaps as communication, mood, knowledge, and experience gaps (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Suffering Model: Patient suffering results from a nurse being unaware of perception gaps due to a nurse-patient conflict. EBP: Evidence-Based Practice; PCC: Patient-Centered Care.

When conflicts occurred, nurses tended to be thinking methodically; for example, they might have been using logical thinking based on EBP or empathetic understanding based on PCC. Meanwhile, patients were experiencing mixed emotions such as anxiety, sadness, dejectedness, and anger. In other words, when we looked simultaneously at both sides’ perceptions of a conflict, we noticed large conflict perception gaps between nurses’ methodical understanding and patients’ mixed emotions. Additionally, we found that perception gaps could, as noted above, arise from gaps in the dimensions of communication, mood, knowledge, and experience. The results suggested that patients did not suffer precisely because of the emotions they were feeling, but rather from their interrelating with a nurse who failed to recognize the gap between their respective perceptions (Figure 1). Below, we present a typical case of a patient suffering because of a nurse’s failure to recognize perception gaps (Case 1).

Case 1: This was the patient’s first experience of surgery. At her first outpatient check-up after leaving the hospital, she complained of feeling nauseated and dizzy. She felt so anxious that she wanted to be re admitted. In addition, she complained of feeling the urge to urinate whenever she was lying in bed.

Our interpretation of this case is as follows. First, the nurse’s assessment of the patient’s physical condition was a clinical judgment based on her experience and knowledge. However, for the patient, it was her first experience, and she wanted to obtain some relief from her feelings of discomfort and the anxiety of not knowing what might happen next by seeking readmission to the hospital (which reflects gaps in experience and knowledge). Regarding the patient’s urge to urinate, she wanted to somehow urinate on her own with the help of the nurse, but the nurse prioritized safety, which conflicted with the patient’s sense of shame (mood gap). Additionally, the nurse’s way of communicating did not fit with the patient’s perspective (communication gap). Since the nurse was unable to accurately perceive the patient’s feelings of anxiety- in other words, because of the perception gaps in this relationship-the patient ended up suffering from feelings of anxiety, sadness, and anger.

When nurses were aware of the perception gaps, their thinking remained methodical, but they picked up on patients’ mixed emotions. We found that a favorable interaction resulted when they demonstrated empathetic understanding toward patients, and shared patients’ suffering (Figure 2). The following case is an example of a favorable interaction arising because a nurse demonstrated awareness of the perception gaps (Case 2).

Figure 2: Model of interaction: Favorable interaction results when a nurse is aware of the perception gaps due to a nursepatient conflict. EBP: Evidence-Based Practice; PCC: Patient-Centered Care.

Case 2: A patient who had had surgery for stomach cancer received a doctor’s report concerning his physical condition. The patient felt he could not possibly accept the report’s findings.

Our interpretation here is that the patient thought that if he were to talk to this nurse, whom he saw regularly, she might be able to understand how he was feeling at that moment (i.e., they had a potential relationship of trust). Then, when he opened up to the nurse about how his felt- that he could not accept the report on his condition- the nurse intimately shared his feelings (empathy). Because she cried as if she herself were ill (shared suffering), the patient could relax (affective exchange). In recognizing the perception gaps, she was able to leverage logical thinking based on EBP and empathetic understanding based on PCC, thus producing a favorable interaction.

This study examined the perceptions of both nurses and patients regarding nurse-patient conflicts.

The most recent interaction perspective on conflict holds that there are unproductive conflicts, which do not produce good results, and productive conflicts, which produce many positive results [27]. The conflict in Case 1 could be considered unproductive in that the patient’s suffering was ultimately unresolved. By contrast, in Case 2, the patient encountered a nurse whom he was able to trust, and this nurse was able to place herself inside the phenomenon that the patient was experiencing. Henderson [11] reported that nurses must identify with a patient’s feelings as if they were in the patient’s skin while, at the same time, recognizing that humans cannot fully understand other humans. In Case 2, in response to the patient’s inability to accept his disease, the nurse saw the patient as a human being, and was able to produce affective exchange through establishing an empathetic connection based her awareness of the perception gaps between her and the patient. The nurse’s cultivation of a favorable interaction may be considered evidence of their exchange being a productive conflict. As described by Travelbee [37], nursing care should be a “mutually meaningful experience” for both the provider and receiver.

The study data were collected using Robbins [27] conflict process. The potential conflicts in Cases 1 and 2 involved nursepatient communication and relationships of trust, respectively. In Case 1, the nurse did not try to fully listen to what the patient was attempting to say, which led to her having insufficient information. In Case 2, the patient assumed that this particular nurse would understand how he felt, and determined that she was a nurse he could trust because of how dedicated she seemed to be to her job. According to Usui [38], nursing care is the process by which nurses actualize their own dreams. She further described how an expert can perceive things that a novice cannot.

This is because, compared to a novice, who can only understand phenomena superficially, an expert can use his or her expertise to see the internal structure of said phenomena. Thus, if nurses can recognize that “communication” and “relationships of trust” are important for nursing care, they must, as professionals, act to achieve effective communication and the building of trust in nursepatient relationships. In this way, there is a need to recognize that nursing skills are not merely skills, but an art, and may require experience to develop fully.

In this study, we determined that there were gaps between nurses and patients in their perceptions of conflict events. First, there was a clear experience gap between nurses and patients. This can be explained by Rogers’ [39] belief that humans systematize their experience in an attempt to give it meaning. Our analysis revealed a tendency for nurses to interpret phenomena by using logical thinking based on EBP as well as empathetic understanding based on PCC. These nurses were trained as professionals and, therefore, could be assumed to have learned to use scientific thinking to interpret perceived events, as well as use their clinical experience to understand how patients felt. Furthermore, nurses could predict how a patient’s condition would evolve from their experience with other cases. On the other hand, when patients experienced further health problems, their lack of specialized training led them to react to phenomena with mixed emotions. For instance, they might become anxious because they have only their own physical experience for reference, and have no foresight about what might happen next.

Second, regarding gaps in communication, Sheppard [40] suggested that both nurses and patients are sending more information than is conveyed through verbal or non-verbal messages. However, a perception gap-namely, a communication gap-occurs if that additional information is not received. Furthermore, it has been suggested that the development of a positive nurse-patient relationship is important for communication and nursing care quality [41-43]. Thus, it is fair to say there is a need to focus on improving that mutual relationship to help eliminate such communication gaps. Third, regarding mood gaps, an individual’s mood and how they feel at a given moment changes with the situation and their physical and mental condition. Furthermore, for busy nurses and the patients receiving their medical care, there may be gaps even in how they sense the passage of time. Finally, as to knowledge gaps, differences in expertise and knowledge about what might occur in the future between nurses and patients are obvious. Even though nurses are, naturally, aware of such differences in knowledge, our results demonstrated that the nurses occasionally did not tailor their explanations of given care to patients’ understanding. It is important to note that these four gaps cannot necessarily be considered individually. Indeed, gaps in communication, mood, knowledge, and experience may occur concurrently.

Gaps between nurse and patient perceptions were shown in the study’s conflict scenarios; however, whether they affected the way a nurse worked with a patient depended on whether the nurse demonstrated awareness (Case 2) or not (Case 1). If nurses have no awareness of gaps in perceptions, they are not likely to think about the emotions a patient might be feeling. By contrast, if they have that awareness, that can begin genuine empathetic understanding.

In this study, we examined how patients experience various emotions due to conflicts with nurses. Affect is a term used to denote the various feelings people experience and is closely linked to emotion and mood [44]. Rogers [27] noted that humans experience emotions as a means of unifying our existence, with emotions being phenomena that express humanity. He also argued that because emotions are subjective, an individual’s nature can never be fully conveyed. In the context of our study, whether a conflict is productive or unproductive is influenced by the affective connection between the nurse and patient. We used the term “affective exchange” in this study to describe the situation in which a patient was able to feel safe and bare their feelings to a nurse who made a decision that affected them-in effect, these patients “sent their affect,” which the nurse openly “accepted.” In Case 1, although the patient was evidently hoping for an affective exchange, the situation made it impossible. In Case 2, the nurse shared the patient’s suffering. Suffering is something felt by an individual or an experience to which they are subjected, and humans perceive their experiences of suffering in their own idiosyncratic ways [37].

In the latter case, the nurse was able to sense and share the patient’s suffering because of the empathetic connection arising from her being aware of perception gaps with the patient. The nurse’s emotional intelligence (EI), or her ability to sense the patient’s feelings, was likely involved. EI refers to an individual’s ability to accurately understand emotions, use emotions to support perception, and reflect on emotions [45], and is believed to increase one’s motivation and interpersonal skills [46]. The concept, as described in Working with Emotional Intelligence [47], has been recognized worldwide. High EI is essential for nurses, who are in a profession that strongly affects people. In particular, nurses must be able to sense and respond to patients’ feelings.

For patients in the midst of painful situations, it is often difficult to communicate their pain. This, coupled with the pain derived from not receiving empathy and understanding, makes their experience doubly painful. The fact that a patient experiences emotions such as anxiety, sadness, dejectedness, and anger does not, per se, constitute suffering. Rather, it is the impossibility for affective exchange with the nurse that does. We believe in sharing the patients suffering from the time a conflict occurs, and as long as the patient’s suffering remains unresolved, by taking an interest in that suffering, adopting the patient’s perspective, and meeting their wishes to the fullest extent possible. Some patients do not have the knowledge, experience, or means to communicate their suffering. For those patients, the key is to what extent the nurse feels concern for their feelings [49,50].

This study has provided some suggestions regarding what competencies nurses require to improve nursing care quality. This begs the question: how does one train nurses to develop those abilities? Furthermore, in what specific environments could nurses optimally leverage those abilities? Further investigation would be needed regarding such interventions. An important limitation of this study is that we did not obtain data by directly interviewing patients. In a future study, we will consider interviewing patients directly. Finally, we might clarify what education would be necessary to help nurses interact with patients in the manner of Case 2.

In forming a conceptual model of nurse-patient conflicts and the nurse¬-patient relationship, we identified gaps in the ways nurses thought and how patients felt. These perception gaps occurred in four domains: communication, knowledge, mood, and experience. By being aware of these gaps, which are caused by conflicts with patients, and sensing patients’ feelings, forging empathetic connections with patients, and sharing patients’ suffering, nurses brought about mutually favorable interactions. In other words, by predicting that a conflict could occur and responding in a manner that was becoming of a nurse, the potential conflict was turned into something productive, which may have contributed to the growth of both the nurse and patient.

What the mutual relationship resulting from nurse-patient conflict becomes depends on one’s perception of “communication” and “relationships of trust.” To paraphrase Florence Nightingale [48] it is a question of a nurse “discerning what she is trying to achieve.” In other words, it may be related to the question of “what kind of human being the nurse is” or to the idea that “ideal nursing care is the way to self-understanding.” One could say, instead, that the unique characteristics of nursing care are the abilities to empathize, intuit another’s needs, and accept another’s fate. In this way, nursing care quality depends on the quality of the nurse.

Nurses, as professionals, do not merely provide technical skills to patients. Instead, they must understand the thoughts and suffering that patient cannot express verbally, and share these with the patient. In doing so, they ready the patient to accept an unacceptable reality, such as cancer. The sharing of suffering may be part of the daily relationship between nurse and patient, which makes it meaningful to consider a part of nursing practice. Doing so will enable nurses to provide higher quality nursing care.