Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Denise Cadle Rhew1*, Susan Letvak2 and Thomas P McCoy3

Received: November 11, 2017; Published: December 14, 2017

Corresponding author: Denise Cadle Rhew, Clinical Nurse Specialist, Research Chair, Cone Health, Greensboro NC, USA

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2017.01.000593

Purpose: To explore the effect of an educational intervention (Geriatric Workshop) on attitudes and knowledge of emergency department (ED) nurses toward the older adult patient and their intention to change their care behaviors toward this population in the emergency department. Two instruments were used for this study: Kogan’s Attitude toward Old People and Palmore’s Facts of Aging Quiz 1.

Setting/Sample: Sixty-seven ED nurses from five emergency departments in one hospital system participated in this study. A total of 44 ED nurses were in the experimental group and 23 ED nurses participated in the control group.

Methodology: Both the experimental and control group received three on-line surveys measuring knowledge, attitudes, and behavioral changes toward older adults. The experimental group attended a Geriatric workshop (educational intervention) and completed the on-line pre-survey and immediate post survey at the workshop in a reserved computer room. The control group completed an on-line pre-survey and immediate post-survey at their convenience on the same day the geriatric workshop was being offered. Four weeks post geriatric workshop offering both the experimental and control group received an on-line post-post survey. Repeated-measures ANOVA were performed to analyze between-group differences over time.

Results: Trends over time improved for the educational intervention group relative to comparison group in Kogan’s Attitude toward Old People and Palmore’s Facts of Aging, but were not statistically significant in repeated-measures ANOVA (all group time interaction p > 0.10). Conclusion and Implication for Practice: A short 4-hour educational intervention was successful in improving ED nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and care behaviors toward older adults. ED leadership needs to support education related to older adults in order to continue to improve outcomes in the fastest growing population.

Abbreviations: ED: Emergency Department; TPB: Theory of Planned Behavior; IRB: Institutional Review Board; KOP: Kogan’s Attitudes toward Older People; PFAQ: Palmore’s Facts of Aging Quiz

The older adult population in the United States (U.S.) is growing faster than any other age group [1]. Older adults have a more complex presentation of diseases and illnesses than any other population due to higher incidences of numerous comorbidities, polypharmacy, and functional impairments [2]. It is not surprising that adults age 65 and older accounted for 19.6 million emergency department (ED) visits in the United States in 2010 [3]. Older adults present to the ED primarily due to a high prevalence of chronic diseases and consequential susceptibility to frequent exacerbation of these illnesses [4]. Indeed, approximately 17% of adults living in the community age 65 and older have at least one treat-and-release ED visit each year. Nurses are the primary health care professionals who provide direct care to older adult patients [1], including in the ED setting.

Research findings reveal that nurses, including ED nurses, acknowledge a personal bias against the older adult, which reflects past experiences with this group or a negative attitude regarding aging [5,6]. The views of nurses toward the older adult patient are vital to the services they provide to this vulnerable population. The literature indicates that healthcare professionals in the ED lack geriatric-specific educational training [4]. Indeed, most nurses who graduated before 2005 did not receive a stand- alone geriatric course in their pre-licensure nursing program [7]. Emergency department nurses report the need to have educational opportunities on how to most effectively care for elderly patients, through prioritizing their care, and recognizing when a physician is needed for their care [1]. Considering that older adults have higher mortality rates and readmission rates, it is imperative that ED nurses have the knowledge and positive attitude to provide the appropriate care needed in the emergency department.

Steinmiller, Routsalo and Souminers (2015) state nurses’ lack of knowledge and positive attitudes may influence the older adult patients’ length of stay, health outcomes, safety, and other carerelated concerns [8]. To assure the highest quality of care to older adults in the ED, it is very important to assess nurses’ current knowledge of and attitudes toward the older adult. Research has demonstrated that educational interventions have improved healthcare providers’ knowledge and attitudes of bariatric patient care [9] cancer care [10], meaningful use of electronic health care records [11] and sexual health [12]. There is little, if any, research evaluating the effects of an educational intervention to enhance nurses’ attitudes and knowledge toward older adults in the ED setting. Thus, the purpose of this study was to explore the effect of an educational intervention on attitudes and knowledge of ED nurses toward the older adult patient and their intentions to change their care behaviors toward this population in the emergency department.

Icek Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) was the framework that helps guide this study. TPB incorporates components that relate to attitudes and the ability to predict behaviors in the presence of certain attitudes [13]. This theory has been useful in explaining healthcare professionals’ behaviors and intentions [14]. The key components of this model used to help answer the research questions were intentions, attitudes, and perceived behavioral control. The key component of this model is behavioral intent. Attitudes concerning the likelihood that a behavior will have the expected outcome, in addition to one’s own evaluation of the risks and benefits of that outcome, heavily influence behavioral intentions. The behavioral change depends on both motivation (intention) and ability (behavioral control) [15].

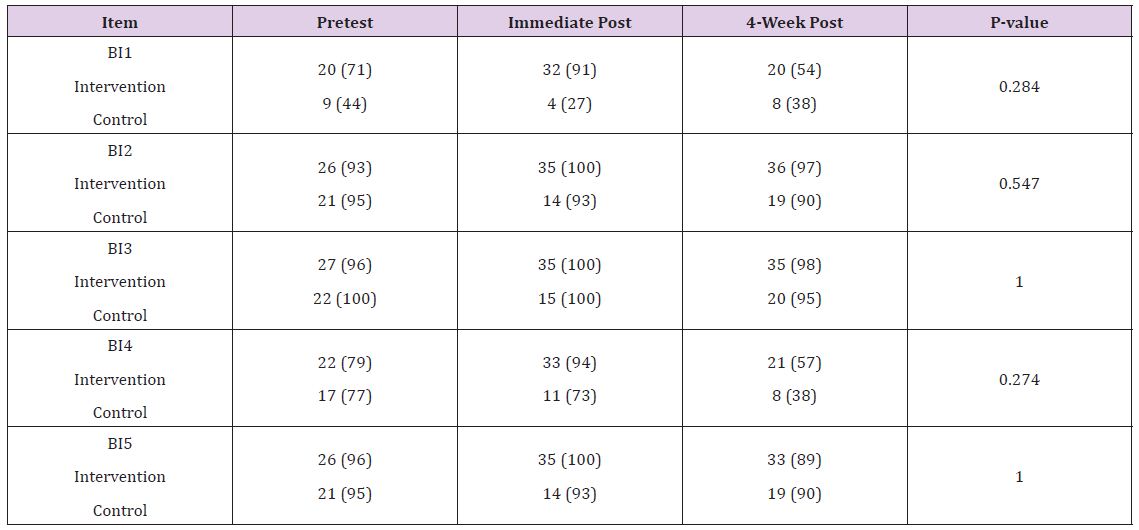

Will an educational intervention aid in identifying ED nurses’ behavioral intentions to change how they care for older adults? For this question, the results from pre-survey, immediate postsurvey and four-week post- survey were compared to evaluate if the educational intervention influenced the experimental group’s behavior intentions to change how they care for older adults. The only question that showed a statistically significant difference between the experimental group and the control group was BI question 10. This question was “I intend to voluntarily request to care for an older adult patient in the next 30 days” (p = 0.30). Specifically, 71% of the experimental group said they intended to request to care for an older adult patient, while only 41% of the control group answered yes to this question. For all BI questions, the experimental group had a higher percentage of yes versus no responses when compared to the control, implying that the educational intervention did influence their intentions to change their behavior in caring for older adult patients. The results are displayed in Table 1 and Table 2.

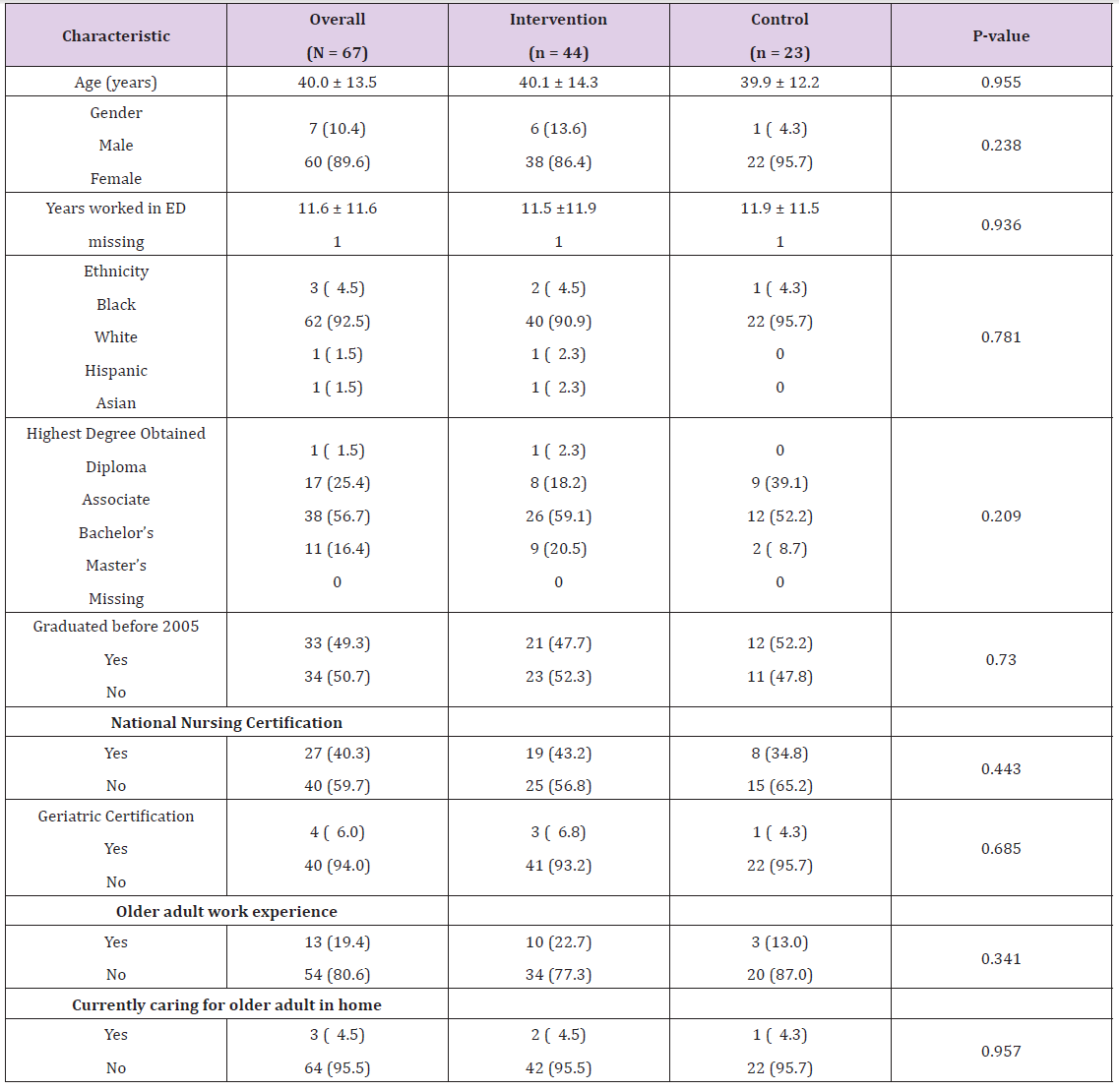

Table 1: Participant Characteristics (N=67).

Note: All numbers are Mean ± SD or N (%); ED = Emergency Department.

Table 2: Behavioral Intention Questions across Time-Points.

Note: BI = Behavioral Intention. Put the entire question wording here.BI1=voluntarily request to care for an older adult; BI2=purposely focus on providing a safe environment for older adult patients within 30 days; BI3=perform a falls assessment on my older adult patients within 30 days; BI4=assess my older adult patients’ need for nutritional consult within 30 days; BI5=assess my older adult patients for signs of depression, dementia, and delirium within 30 days. P-value is for Fisher’s exact tests of group differences at 4-week post time-point.

Emergency department nurses who receive an educational intervention on geriatric nursing care will have higher overall aging knowledge scores at immediate post education intervention and four weeks post education intervention than those ED nurses who did not receive the educational intervention (H1), and ED nurses who receive an educational intervention on geriatric nursing care will have higher positive attitude scores at immediate post education intervention and four weeks post education intervention than those ED nurses who did not receive the educational intervention (H2).

A two-group quasi-experimental, longitudinal pretestimmediate posttest and four-week posttest design of nurses working in five EDs within a large healthcare system comprised the design for the study.

Convenience sampling was used to recruit participants. All nurses in five emergency departments in one healthcare system received an email requesting their voluntary participation in the study. Flyers were posted in each emergency department to notify the ED nurses of the geriatric workshop and their opportunity to participate in a research study. The researcher also performed face-to-face recruitment in each ED. The criteria for inclusion in the study were licensed registered ED nurses and: a) employed by the health system, b) age 18 or older, and c) understood and spoke the English language. The final sample was 67, with 44 ED nurses in the experimental (intervention) group and 23 ED nurses in the control group. The hospital system employs approximately 300 ED nurses at the five EDs; the participation rate was approximately 22%.

The setting for this study was a large healthcare system in the Southeastern United States that consists of five emergency departments and cares for approximately 750 patients daily. The educational intervention was held in five different classrooms in the staff educational department owned by the health system.

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was first obtained from the participating hospital system and university. As stated above, ED nurses were recruited through the healthcare system’s electronic mail system. An email was sent to all ED nurses, which included an electronic letter explaining the purpose and importance of the study along with how to sign up if they were able to attend the four-hour geriatric workshop. If they were unable to attend, information was given to them on how they could participate by completing the surveys via a link that would be sent out to them electronically. Those participants that attended the workshop had access to a computer to complete the pretest and immediate posttest. Access to the link for the pretest and immediate posttest were made available through any computer that had internet access. The control group completed the pretest survey the same day as the Geriatric workshop and they had a week to complete the immediate post survey.

All nurses who completed the surveys within the allotted time frame were included in the data collection. Per the IRB, completing the pretest, immediate posttest, and 4-week posttest surveys implied informed consent from the participant in the study. Only an electronic survey was used to collect data from the control group. Instruments administered included Kogan’s Attitudes toward Older People (KOP), a self-administered questionnaire consisting of 34 statements divided into 17 positive statements and 17 negative statements [16]. Reliability coefficients have been published as 0.70 for the positive scale and 0.85 for the negative scale [16]. Knowledge was assessed using Palmore’s Facts of Aging Quiz (PFAQ), which contains 25 true and false questions [17]. The PFAQ instrument has been used widely over the past twenty-five years. The reliability of the instrument was determined through an internal consistency coefficient measured by Cronbach’s alpha with scores ranging from 0.50 to 0.80 among studies and study populations Palmore [17]. The range of Cronbach’s alpha scores indicates that the test has a medium to moderately high degree of internal consistency reliability [18].

Five questions developed by the first author pertaining to intentions regarding providing care to the older adult patients were additionally asked near the end of the survey. A pilot group of twelve nurses was used to test the reliability and validity of the intention questions prior to the study. Demographic questions were asked at the end of the survey and included: age, gender, race, years in nursing, if they received specific geriatric courses in their nursing program, highest level of education completed, and if they currently cared for an elderly family member Palmore measured content validity with his gerontological students by assessing their scores after completing a geriatric course, and then compared quiz results [17]. Palmore (1992) found that after completing a geriatric course, the students who completed the course consistently scored higher on posttest than they did on the pretest [17]. Multiple studies have shown that instrument results suggest that groups of subjects with similar education levels or backgrounds have similar mean scores, thus supporting the face validity of PFAQ [17-20].

An a priori power analysis revealed that a sample size of 50 (25 per group) was sufficient to detect an effect size of 0.404 with 80% power using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), assuming a moderate correlation (0.50) of repeated measures. Descriptive statistics were estimated for patient characteristics overall and compared by intervention groups using t-tests or Mann- Whitney U tests for continuous variables and Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. Differences between groups in behavioral intention questions at 4-weeks post-intervention were similarly compared. Trends over time in PFAQ and KOP were analyzed for differences between intervention groups using mixed between-within repeated measures ANOVA (RM-ANOVA). Data were analyzed utilizing SPSS version 22. A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Characteristics of the sample are described in Table 1. The current attitudes of ED nurses toward older adults using the KOP at pre-intervention (RQ1) had an overall mean positive score across groups of 78.6 (SD = 8.9) out of a possible highest score of 119. At pretest, mean negative score across groups was 44.6 (SD = 11.0) out of a possible 119. The current knowledge of ED nurses about older adults using the PFAQ (RQ2) at pre-intervention had an overall mean knowledge score across groups was 13.8 (SD = 2.1) out of a possible highest score of 25 demonstrating a lack of knowledge. The educational intervention did aid influence ED nurses’ behavioral intentions to change how they care for older adults (RQ4). The experimental group had a higher percentage of yes versus no responses when compared to the control group (Table 2).

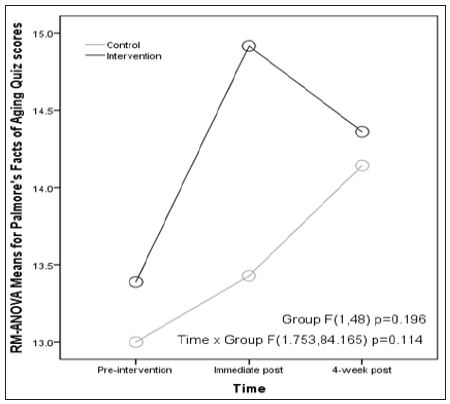

Based on RM-ANOVA, H1 was not supported. For RM-ANOVA of PFAQ, assumptions of sphericity were not satisfied (p = 0.005) requiring the use of Huynh-Feldt correction ε = .877; however, the assumption of equal group covariance matrices was satisfied (p = 0.444). Here, RM-ANOVA analysis revealed a main effect of time (F (2,96) = 15.955, p = 0.003), but no main effects of experimental vs. control group (F(1,48) = 1.717, p = 0.196), and no significant interaction effects of group by time-point (F(1.753,84.165) = 2.295, p = 0.114) (Figure 1). Mean scores increased in each group at immediate post-intervention but decreased at 4-week postintervention for the intervention group. Effect sizes using partial eta-squared were small-to-moderate for group main effects (Ƞ2 p = 0.35) and small for group by time interaction effects (Ƞ2 p = 0.046).

Figure 1: Trends over Time for Palmore’s Facts of Aging Quiz Scores from Repeated Measures ANOVA

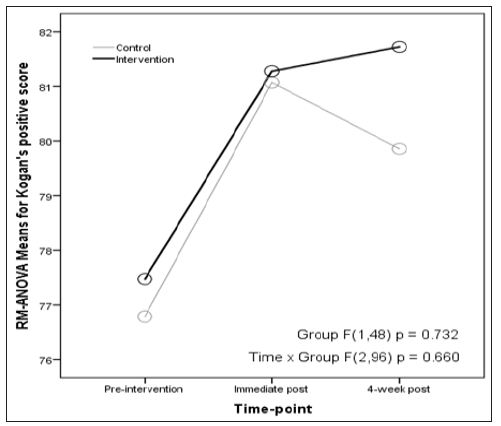

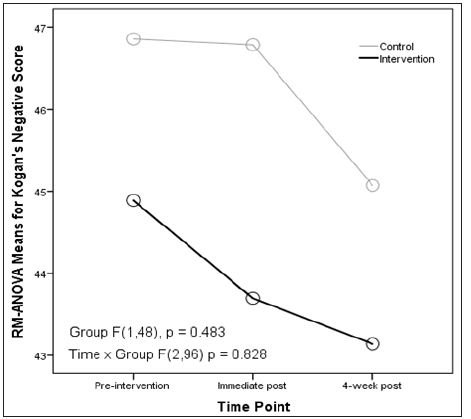

H2 was also not supported given RM-ANOVA findings. KOP positive scores, assumptions of sphericity (p = 0.600) and equal group covariance matrices (p = 0.334) were reasonably satisfied. Making these assumptions, analysis revealed main effects of time (F(2,96) = 11.444, p = 0.001), but no main effects of experimental vs. control group (F(1,48) = 0.118, p = 0.732), and no significant interaction effects of group by time-point (F(2,96) = 0.418, p = 0.660) (Figure 2). Mean scores again went up in each group at immediate post-intervention in similar fashion but decreased at 4-week post-intervention for the control group. Effect sizes using partial eta-squared were small for group main effects (Ƞ2 p = 0.002) and group by time interaction effects (Ƞ2 p = 0.009). For RM-ANOVA of Kogan’s negative scores, assumptions of sphericity (p = 0.068) and equal group covariance matrices (p = 0.444) were reasonably satisfied. Making these assumptions, analysis revealed no main effects of time (F (2,96) = 1.394, p = 0.253), no main effects of experimental vs. control group (F(1,48) = 0.501, p = 0.483), and no significant interaction effects of group by time-point (F(2,96) = 0.189, p = 0.828). Effect sizes using partial eta-squared were small for group main effects (Ƞ2 p = 0.100) and group by time interaction effects (Ƞ2 p = 0.004) (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Trends over Time for Kogan’s Positive Scores from Repeated Measures ANOVA.

Figure 3: Trends over Time for Kogan’s Negative Scores from Repeated Measures ANOVA.

This study of ED nurses’ attitudes and their knowledge of older adults revealed several interesting findings. The participants had mean years of ED tenure of 11 years which is high given that nationally the ED turnover rate is 21.7% [21]. (This study also had a slightly higher percentage of male participants (11.4%) compared to the state and national percentages of 7.5% and 9.1%, respectively [22,23]. Also, 40% of the participants had a national certification, which is higher compared to the national rate of 35% [22] (HRSA, 2013). However, 81% reported they did not have any specialized geriatric training, which is consistent with reports that ED nurses do not have geriatric specialized training [4]. This study found that ED nurses had overall positive attitudes towards older people which is contrary to previous studies.

A reason that these participants may have higher positive attitudes toward older patients is that three out of the five hospitals in this study are a part of the NICHE program, meaning Nurses Improving Care for Health System Elders. The hospitals focus on improving care of the elderly and do provide continuing education on the older adult population. The hospital system also offers a geriatric symposium yearly that was held a few months before this study and any nurse in the system can attend. The literature also reported that nurses with higher education tend to have positive attitudes toward the older adult [24] and many of these participants had advanced nursing education. Another possible reason for having positive attitudes is that the participants who chose to take part in this research study liked caring for older patients in the ED.

The ED nurses in this study had low levels of knowledge of caring for older adults which is consistent with the literature. However, neither hypothesis was supported in this study. While there were improvements in post-intervention knowledge and attitude scores, the improvements were not statistically significant. These findings contrast with other studies of health care professionals which showed statistically significant improvements post educational intervention. Other educational intervention studies of ED nurses showed improved skills with recognizing signs of anterior myocardial infarction [25], identifying and classifying pressure ulcers, [26] and improving assessment and discharge planning for older adults [27,28].

A possible reason for the lack of statistically significant results is that the 90 minutes of mini-geriatric lectures and two hours of interactive educational stations were not the appropriate teaching strategy for these participants. Participants may have benefited from other didactics opportunities such as web-based learning because they could complete the educational offering when they had adequate time, instead of only being able receive the educational once. Participants may have been able to retain the information better if they could have reviewed the education at their own pace and time so they could refer back to the educational material if they need refreshers. Additionally, much of continuing education has become web based, and these learners may prefer and learn better from web based educational programs that they can complete at their convenience.

A limitation of this study was the use of a convenience sample and quasi-experimental design, which limit generalizability. The use of the Palmore’s Facts of Aging quiz was also a limitation due to being the only tool available to measure participant’s knowledge on facts of aging. This study was limited to nurses from five EDs within one large healthcare system in a single state. Another limitation to recruiting participants for the control group was that many nurses were likely working when they accessed the survey and did not have time to fully participate or got interrupted due to patient care needs. Finally, ED nurses’ motivation in participating in the study could also be a limitation of the research, as the nurses did not get paid to attend the workshop. Four nurses canceled their registration to participate once they realized they were not getting paid.

This study demonstrates a lack of knowledge in caring for older adults in ED nurses. While scores improved after the educational intervention, this study did not demonstrate significantly improved attitudes or knowledge scores towards the care of older adults. Thus, it is suggested that the use of a geriatric workshop as an educational intervention alone may not be enough to increase overall aging knowledge and improve positive attitudes toward older adults among ED nurses. Different educational strategies, including web based educational programs, or provide simulation case scenarios which may be more effective. Further research is recommended on strategies for improving ED nurses’ attitudes and knowledge of older adults.