Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Andrew Rajkumar1, Karl Payne2*, Alexander Goodson3 and Arpan Tahim4

Received: November 15, 2017; Published: December 01, 2017

Corresponding author: Mr Karl Payne, Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Specialist Registrar, West Midlands Deanery, UK

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2017.01.000559

End of life care in head and neck cancer (HNC) is a complex process, addressing symptomatic, functional and psychosocial needs. In order to provide a high level of care the role of each member of the palliative care multi-disciplinary team (MDT) is vital. This review article discusses end of life care in HNC and the palliative care pathway. We highlight the contribution of each palliative care MDT member and the role of the head and neck surgeon in end of life care.

The World Health Organisation define palliative care as: “an approach that is aimed at improving the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problem associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial and spiritual”[1]. For the head and neck cancer patient who presents with advanced, incurable or recurrent disease, the role of palliative therapy is vital to ensure both quality of life and quality of dying, with as far as possible a symptomless end of life. Current estimates are that 60% of patients with head and neck cancer present with stage I or II disease, and of those 40% presenting with advanced disease, 10% will have metastatic “incurable’ disease at presentation [2]. Furthermore, as five-year survival data for head and neck cancer approaches two thirds [3], it should be at the forefront of the head and neck surgeons mind that one third of patients will require some form of palliative care. This essay will discuss the impact of the specialist palliative multi-disciplinary team (MDT) upon the head and neck cancer patient, briefly describing non-oncological palliative care treatment modalities and their application by various members of the palliative MDT.

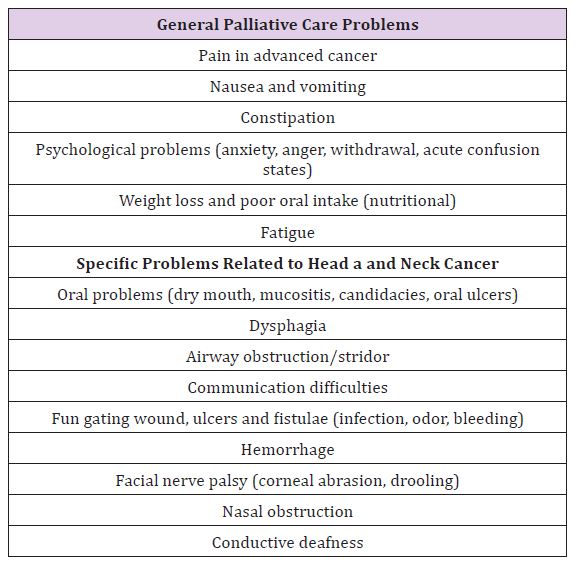

It is paramount for the modern surgeon to appreciate the needs of the palliative head and neck cancer patient; hence having a thorough understanding of the reasoning behind specific palliative care interventions. Palliative interventions are directed by patient presenting signs and symptoms (Table 1). However, palliative care of head and neck cancer is further complicated by site specific squeal that arise in the location of the tumour. Such symptoms are dysphagia, oral problems, and airway obstruction with feeding and communication difficulties. Tumour fumigation, fistula formation and hemorrhage are serious end-stage consequences [4,5]. As can be seen, these are complex and distressing outcomes that require specialist input. In 1987, palliative medicine was recognized as a medical specialty [6]. Palliative medicine provides care relating to symptom management, management of complex psychosocial and spiritual issues, terminal care, and decision making in uncertain progressive situations [6]. In the UK, palliative care services are offered in hospital, community (including hospice care), and outpatient clinic/day therapy settings.

Table 1: Palliative care problems experienced by head and neck cancer patients.

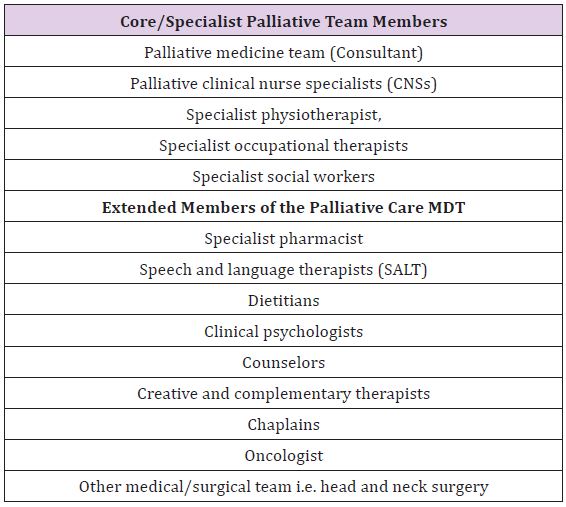

This palliative care service is delivered as part of a specialist MDT, co-operating with numerous other specialties, including head and neck surgery. According to the NHS England Cancer Quality Improvement Network System and the Royal College of Physicians, the palliative care MDT comprises of ‘core/specialist’ and ‘extended’ members [6,7]. Core/specialist members include the palliative medicine team, palliative clinical nurse specialists (CNSs), specialist physiotherapist, specialist occupational therapists and specialist social workers. Several extended members, together with the primary surgeon and oncologist make up the MDT (Table 2). The need for such a diverse MDT becomes apparent when one considers the medical, ethical and psychosocial challenges that arise in end of life care [8]. As Schuman [8] state, palliative care requires “proactive consideration of quality of life, functionality, symptom control and other patient-centered objectives” [8]. At times these factors can be in conflict and the ‘team approach’ is essential to balance needs of care.

Table 2: Members of the specialist palliative care MDT.

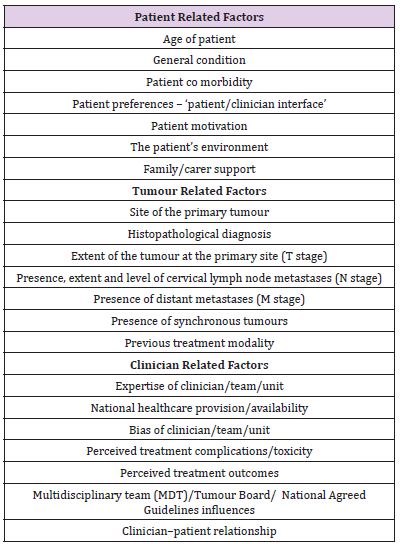

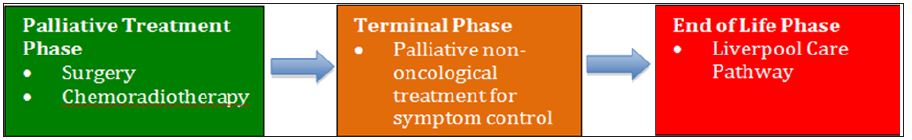

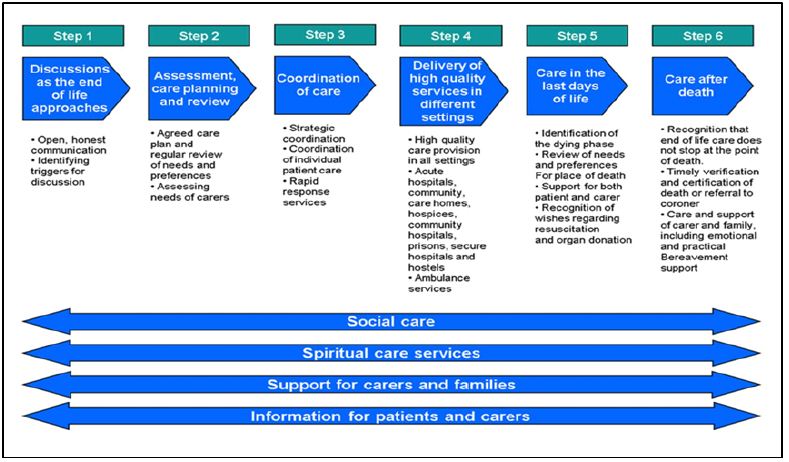

The palliative needs of a patient should be addressed at initial treatment planning and regularly throughout on-going phases of treatment [2]. If not already involved, the onus is on the surgeon to seek help from a CNS and/or Consultant in palliative medicine [9]. Roland and Bradley listed factors that influence the palliative care decision-making process for head and neck cancer patients. They separated these into patient, tumour and clinician related (Table 3) [2]. With these factors in mind, the planning and provision of palliative care should begin as soon as incurable head and neck cancer is diagnosed, and continue until death; utilizing a MDT approach. The palliative care pathway begins with surgical or nonsurgical oncological treatment to prolong life, followed by terminal non-oncological symptom control and progression onto the end of life pathway (Figure 1). The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) describes 6 steps for end of life care to ensure all needs of the patient and family are met with co-ordination of relevant services (Figure 2). In the UK, the Liverpool Care Pathway currently guides end of life care.

Table 3: Factors that influence the palliative care decisionmaking process for head and neck cancer patients.

Figure 1: The palliative care pathway.

Figure 2: NICE 6 steps for end of life care.

The location where terminal patients receive treatment should enable a pain free, peaceful and dignified death, with relatives presents [10]. Ideally, the patient should be allowed to decide where they wish to die. The location may also govern the quality of care patients receive and the provisions in place to ensure this care is delivered; such as access to palliative care specialists in hospices, or Macmillan CNSs at home. A recent study by Kamisetty et al. [11] found that for UK oral cancer patients treated with palliative intent, 34% died in hospital, 22% in a hospice, 22% in their own home, and 22% in a nursing, residential or old people’s home. In a similar study, assessing UK head and neck cancer patients, Ethunandan et al. [10] reported 63% died in hospital, 19% in a hospice and 16% at home. Despite long held social opinion that dyeing at home is preferable, this group argued that the shift to hospital deaths is due in part to a societal change in pastoral and family support. They also noted that the reliance, especially in complex head and neck cancer patients, on technology may be driving palliative care towards the hospital setting. Whilst a hospice setting arguably provides the best access to technology and the palliative MDT, this group reported 53% of patients requiring emergency admission in the final month of life that led to terminal events.

The establishment of specialist centers and specialist palliative care networks is a requirement of the NHS National Cancer Peer Review Programme [12]. Such ‘Expert Centers’ can provide improved psychosocial support to patients and families and better contact between head and neck surgeons with patients and families [13]. Kwon et al. [33] described the characteristics of patients attending a ‘supportive care centre’ (this name was chosen because the term ‘palliative’ was seen as a barrier to referral from physicians) [14]. They grouped patients into ‘early referrals’ (expected survival > 2years) or ‘late referrals’. A significantly greater proportion of early referral patients had head and neck cancer, compared to the late referral patient group (67% vs 6%). These patients were younger, less likely to be married, more likely to suffer from alcoholism and attended services more regularly. This data has ramifications for head and neck surgeons, and the early attendance and referral of such patients to palliative services. The outcome of the above findings is that while head and neck surgeons should respect patient’s wishes regarding location of palliative treatment, they should be increasingly prepared to facilitate and partake in the palliative pathway in hospital as these numbers increase. Furthermore, as Kwon et al [33]. Demonstrate, head and neck cancer patients are more likely to seek palliative care earlier, and thus may present to the head and neck outpatient clinic with palliative needs.

In the UK, we are fortunate to have access to head and neck oncology and Macmillan palliative CNSs. These nurses are based either in hospital or the community and play a significant role in specialist palliative services in the UK [16]. In a qualitative descriptive study, Howell. Investigated the activities and patient interactions of community palliative care CNSs [17]. They described how palliative CNSs act as ‘liaison points in a complex health service’ and were involved in the assessment, care planning, intervention and evaluation of terminal patients. In such a difficult time for both patients, careers and relatives, CNSs require the ability to make real-time decisions, co-ordinate care in complex situations, and communicate between several teams. Furthermore, CNSs provide the emotional care and support for cancer patients, often overlooked and not delivered elsewhere [18]. CNSs appear to have key roles both in the hospital setting and the hospice/community. CNSs have been reported as acting as triage leaders for the hospitalbased palliative care team; improving the triage process, team efficiency and timely access to care for patients and families [19]. In a similar leadership role, Brockis examined the function of a palliative CNS in the emergency department and acute medical unit [20]. They found that for patients with palliative and end of life needs, 15% were assessed early by the CNS and avoided admission with discharge back home or directly to a hospice. In addition they were able to reduce hospital stay and provide early provision of specialist palliative care for those patients admitted. In the hospice environment, in addition to routine care, CNSs have a key managerial role to facilitate palliative care meetings and adhere to the palliative care ‘gold standards framework’ [21]. While the above roles of CNSs seem generic to all cancer patients, these interactions will overlap with head and neck cancer patients. Furthermore, as previously mentioned, the location of head and neck cancer creates specific palliative symptoms related to airway and eating/speaking difficulties. Macmillan and palliative CNSs receive education, often at a postgraduate level, specific to their field and are therefore experts in managing terminal head and neck cancer patients [22]. It can be seen from the above, that CNSs are truly the lynch pin in the delivery of specialist palliative care. They will be the first port of call for patients in outpatient head and neck cancer services [23], and will assess and co-ordinate both hospital and community based palliative care for head and neck cancer patients.

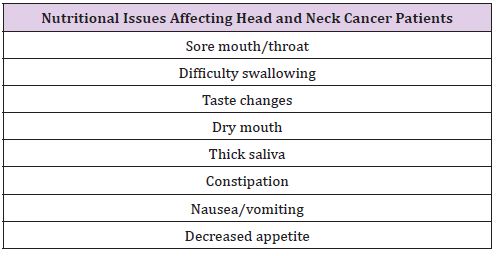

As described, the palliative care MDT comprises of extended members. In this section we discuss the role of several of these teams. Specialist dietitians are able to provide nutritional counseling and provide oral nutritional supplements to palliative head and neck cancer patients. As Ardillo states of head and neck cancer patients: “the unique set of side effects of the disease process and treatment cause the patient to develop nutritional challenges” [24]. In a recent review, Hayward and Shea listed factors relating to nutritional issues in head and neck cancer patients (Table 4) [25]. It can be seen that the impact of these issues upon the nutritional needs of head and neck cancer patients can be complex, requiring calculation of protein, calorific and fluid requirements, and may require supplemental feeding [22]. The SALT team plays a key role in the assessment and recommendation of treatment for head and neck cancer related dysphagia. The SALT team can also provide screening before treatment (such as radiotherapy) to provide information on the impact of this therapy upon swallowing and communication [26]. In the palliative patient, this may involve the prescription of food thickeners, or referral for a gastrostomy tube. It is the responsibility of the head and neck surgical team to be able to recognize swallowing difficulties and refer appropriately to SALT. For the terminal head and neck cancer patient, the outcome may be conservative management, nonetheless the SALT team can provide practical advice and support for such patients. For this purpose, Zuydam et al. [27] have described the use of the University of Washington Quality of Life swallowing domain and the MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory, as useful tools to grade when a referral to SALT is required and to grade the impact of swallowing difficulties upon the patients QOL [27]. Physical exercise and physical therapy have been shown to have beneficial effects for palliative cancer patients: improving quality of life, physical and psychosocial functioning [28]. Treatments that are offered by palliative physiotherapists include: physical exercise (standing, walking, etc), relaxation therapy (massage) and breathing treatment. In a randomized clinical trial of terminally ill cancer patients, a combination of massage and physical exercise was shown to significantly reduce pain and improve mood [29]. Further evidence exists for the overall psychosocial benefit of physical therapy to promote coping with symptom burden [26].

Table 4: Nutritional issues affecting head and neck cancer patients.

One of the mainstays of care delivered by the specialist palliative team takes the form of various drug therapies. For this reason palliative drug therapy is discussed below. Palliative drug therapy commonly includes a variety of analgesics, combined with other symptom controlling medication such as anti-emetics, cough suppressants and corticosteroids [30]. One of the most common symptoms experienced by terminal patients with head and neck cancer is pain [4,5,30]. WHO guidance is clear regarding the analgesic ‘pain ladder’ and the escalation from non-opiod drugs, through to weak and then strong opioids. Whilst this assumption of cancer pain needing appropriate analgesics in the palliative phase is straightforward, evidence exists that both environment and healthcare worker education impacts upon the amount and thus adequacy of palliative pain control. Lin et al. [5] demonstrated that morphine doses significantly increased when head and neck cancer patients were admitted to a hospice. As the level of education of staff increased, so did morphine doses; noting a continued misunderstanding and fear of strong analgesics among health professionals. Furthermore, they stated that the education level of patients impacted upon correct opioid dosage, with those of a low education level fearful of ‘the myth of addiction’. Interestingly, in their patient cohort, tongue cancer required higher doses of morphine than laryngeal, oropharyngeal and floor of mouth cancer. The key finding from this study was that survival time significantly increased with change in morphine dosage. To evaluate the impact of drug therapy upon palliative treatment in head and neck cancer patients, Bisht et al. [30] assessed quality of life (QOL) at baseline and then 1 and 2 months after the initiation of treatment [30]. Most frequently prescribed drugs were analgesics, but patients also received cough suppressants, anti-emetics, multivitamins, anti-ulcer agents, corticosteroid and antibiotics. Patients received a mean 8.7 different drugs. They demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in QOL and reduction in pain score, with the use of correct palliative drug therapy in this cohort. Especially important in head and neck cancer patients, is the method of drug administration, taking into account the symptoms of dysphagia and other oral difficulties [10]. Devices such as syringe drivers provide continuous infusions, often of multiple drug cocktails, and can facilitate an easier transition from hospital care to the home environment. Clearly, as surgeons and members of the palliative MDT, we should be educated and able to competently prescribe palliative drugs and recognize patients with increased needs. In this aspect of care the palliative medicine team and pain team can be very valuable.

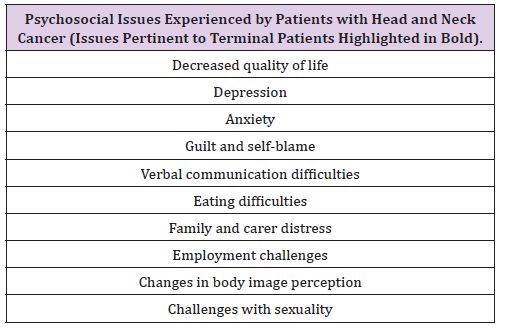

Treatment for head and neck cancer, both the surgical and palliative/terminal phase have a profound impact upon the psychosocial well being of the patient. It is established that head and neck cancer impacts upon several facets of quality of life [31,32] and the psychosocial challenges faced by head and neck cancer patients are many and complex (Table 5) [33]. For the terminal patient, manifestations of psychological distress, such as depression and anxiety, can have an adverse outcome on the quality of dying. In a study of 481 terminal cancer patients and 381 carers, Chang et al. reported that the level of ‘burden of care’ was the factor that most predicted satisfaction about overall care in both patient and carer groups [34]. For these reasons, the psychosocial support provided by the specialist palliative care team is invaluable for the terminal head and neck cancer patient. Palliative medicine doctors and especially CNSs are experienced in dealing with these patients and their emotional needs [18]. When required, psychologists and psychiatrists can be added to the extended MDT to deliver psychological therapy and/or medication.

Table 5: Psychosocial issues experienced by patients with head and neck cancer (issues pertinent to terminal patients highlighted in bold).

Despite not being part of the formal MDT, the involvement of family and carers in the care of the terminal head and neck cancer patient should not be overlooked. Specifically the care provided, but also the impact of the cancer upon the family and carers. Family members often assume the role of a carer, feeling enormous responsibility and emotional burden. The demands of care lead to significant practical life changes, and induce financial and psychological effects upon the family [35]. Interestingly, it is often the carers that feel a greater burden of care than the patients [34]. Verdonckde Leeuw demonstrated that 20% of partners of head and neck cancer patients had clinically significant levels of emotional distress; this was related to the presence of feeding tubes, feeling worried and incapable of taking action, and due to disruption in daily living [36]. Furthermore, the patients themselves perceive this burden of care. In a recent survey of 386 head and neck cancer patients, Precious et al. [36] identified nearly half of patients having family members as carers, with one third feeling that their care was a considerable burden and ‘very hard’ for their careers [37]. The palliative care team should be aware of the limitations of care that families can provide and the impact of this care giving upon their lives. For the surgical team, the awareness of such a caregiver burden is imperative. As the clinician seeing the palliative patient regularly, in the outpatient or inpatient setting, we are best placed to offer support. Providing clear information related to the cancer and the specific care requirements of the terminal patient can be useful for carers to understand the care provided and the overall process of dying. Furthermore, self-help groups can be recommended or carers directed for further support, often from the palliative care CNS.

The above sections have described the members of the palliative MDT and the care they provide, with the aim of highlighting areas where the surgeon can interact and assist this process. It can be seen that the head and neck surgeon is most likely to be involved in the palliative and terminal phases of care. However, other specific roles are worth mentioning. Firstly, as surgeons with a knowledge of oral pathology we are best placed to deliver guidance when managing the oral problems experienced by palliative patients [2]. As listed in Table 1, these include dry mouth, mucositis, candidacies and oral ulcers. The surgeon can also influence the patient perception of psychosocial support. Ledeboer et al. [13] reported a positive relationship between a single surgeon attending to patient care and higher levels of psychosocial support [37]. They also reported that communication between the surgeon, MDT and patient/family was poor and an MDT logbook to improve continuity of care resulted in a reduction of psychological problems. Finally, surgeons are arguably best placed to evaluate the impact of palliative care interventions upon QOL, from the beginning of treatment to the terminal phase. Thus, we have a key role in ongoing palliative care research.

In summary, palliative care should be thought of as an on-going continuum during head and neck cancer treatment once active therapy has ceased, not just end-of-life care. The head and neck surgeon should be aware of the problems facing terminal head and neck cancer patients, with knowledge of how to treat and when to refer such patients. Where possible, involvement of the specialist palliative team should be sought early in the palliative pathway. Furthermore, an understanding of the members of this team and the extended members of the MDT is crucial in meeting the diverse and complex needs of palliative and terminal head and neck cancer patients. Finally, the needs of family and carers should always be borne in mind, with the confidence to involve clinical nurse specialists or other support groups/resources. Upon writing this essay I am reminded of the favorite saying of my former Consultant in Clinical Oncology: “palliative and end of life care is the most important care you will you will ever deliver to a patient, unlike other areas of medicine you only get one chance to get it right!”. Head and neck surgeons and all members of the palliative MDT would do well to remind ourselves of this.