Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Rashi Juneja1 and Dweep Chand Singh2*

Received: September 04, 2017; Published: September 19, 2017

Corresponding author: Dweep Chand Singh, Associate Professor, AIBHAS, Amity University UP, NODA, India

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2017.01.000367

Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) is a common psychiatric disorder that frequently presents to both mental health experts and general health practitioners. Generally, BDD for the most part, goes unrecognized and undiscovered in clinical settings. It is critical to perceive and precisely analyze BDD in light of the fact that this often secret disorder might be crippling. Patients with BDD have impaired functioning, poor quality of life, a high rate of self-destructive ideation and suicide attempts. In this way, it is essential to screen patients for BDD and abstain from misdiagnosing it as another disease. Non-psychiatric treatments (e.g., medicinal and / or surgical) which most patients look for and get inadequate for BDD. This article presents a clinically engaged outline of BDD symptoms, causes and analyses long term effects of psychotherapy on it.

Keywords: Body dysmorphic disorder; Psychotherapy; CBT

Abbreviation: BDD: Body Dysmorphic Disorder; OCD: Obsessive Compulsive Disorder; OCRDs: Obsessive Compulsive and Related Disorders; CBT: Cognitive behavioral therapy; RCTs: Randomized Controlled Trials; SSRI: Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor; CFT: Compassion focused therapy

A somatoform disorder, wherein the afflicted individual is concerned with body image, manifested as excessive concern about and preoccupation with a perceived defect of their physical appearance and a fear of being evaluated negatively by others (F45.22 of ICD-10) WHO [1]. According to DSM-IV American Psychiatric Association [2]. Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD) is a condition where the individual spends a lot of time being worried and concerned about their looks and appearance. A person inflicted with this disorder may:

a) Focus on an apparent physical defect that other people cannot see OR

b) Have a mild physical defect, but the concern about it is out of proportion to the defect.

Body Dysmorphic Disorder is reported as an unremitting and chronic condition in which the individual or sufferers experience high rates of being housebound, hospitalization, suicide attempts, and completed suicide Phillips & Menard [3].

Symptoms of BDD include comparing own body part to others’ appearance, camouflaging (with body position, clothing, makeup, hair, hats, etc.), seeking surgery of the perceived defective body part, checking in and avoiding mirror, excessive grooming, skin picking,changing clothes excessively, excessive exercise etc. Individuals with BDD may avoid daily activities including socializing, work and school; in extreme cases affected individuals may become housebound, sufferers are at a high risk for hospitalization especially in psychiatric wards, suicidal ideation, attempts and completed suicide.

Having BDD means one also has dysmorphophobia. Social effects of BDD may include feelings of isolation, being alone and unwanted Jaffe [4], feelings of guilt, shame and embarrassment, trouble in engaging with peers and interacting with them, trouble developing and maintaining friendships and relationships, avoid school, work, or other social situations, deterioration in performance and fear of bodily persecution Brewster [5]. Among the causes of body dysmorphic disorder are multifactorial variables including psychological, socio cultural and biological.

Neuropsychological aspect and cerebrum imaging have showed that there might be affected because of frontostriatal and temporoparietaloccipital circuits. There are no known causes of body dysmorphic disorder. It is believed that the genetics, social, psychological and cultural factors, all play role in the development of BDD. Many also believe that an event may trigger the manifestation of BDD Hunt, Thienhaus & Ellwood [6]. Research indicates that patients with BDD have reduced serotonin levels than normal. No one knows exactly what causes BDD. However, newer research suggests that there are a number of risk factors that could mean that one is more likely to experience BDD, such as bullying, abuse, low self-esteem, fear of isolation, perfectionism, genetics, anxiety and depression.

Research suggests that although BDD is classified as a somatoform disorder in the DSM-IV-TR American Psychiatric Association [2], it shares many phenomenological and symptom variables with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) Neziroglu and Yaryura-Tobias [7]. It meets most of the criteria to qualify as an obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorder, such as the presence of obsessions and compulsions McElroy et al. [8].

Patients of BDD tend to display repetitive behaviors that resemble the compulsions characteristic in OCD. Body Dysmorphic Disorder involves an obsession with either physical appearance or with a particular body part. If it involves the muscularity of the whole body then it is termed as “muscle dysmorphic” Pope et al. [9]. Also, reclassification of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) out of the Anxiety Disorders category and into a new diagnostic category of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders (OCRDs) has occurred in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-Fifth Edition American Psychiatric Association [10]. The proposed OCRDs include body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), hair-pulling disorder (known as trichotillomania), skin picking disorder and hoarding disorder. Another disorder that is required to be differentiated from BDD is Hypochondriasis.

When we compare the two within the DSM they do differ in their description. Hypochondriasis has more of somatic symptoms which are about perception of illness whereas BDD is about physical appearances. In other words, persons with Hypochondriasis are mainly concerned with symptom’s meaning where in BDD person is concerned with the fact that the perceived abnormality is there at all. The preoccupation in hypochondriasis is with the bodily functions (e.g., heartbeat or sweating); with vague and ambiguous physical sensations (e.g., an aching body part) or with minor physical abnormalities (e.g., a small sore or an occasional cough).

The individual attributes these symptoms or signs to the suspected disease. Repeated medical examinations and reassurance from physicians do little to relieve the concern about bodily disease. Individuals with hypochondriasis may become alarmed by reading or hearing about disease, from observations, knowing someone who becomes sick, sensations, or occurrences within their own bodies. Social anxiety or Social phobia disorder is another disorder diagnosis, which often gets confused by BDD. Social phobia is characterized by extreme anxiety about being judged by others or acting and behaving in a way which might lead to embarrassment. Individuals with social phobia believe that others are going to criticize or scrutinized them and this mostly leads to anxiety, which in turn often leads to panic-like symptoms including heart palpitations, shortness of breath, excessive sweating and faintness. The central fear of social phobia is embarrassment over the way the individual might act and the anxiety generally is triggered by specific social circumstances.

BDD patients have a high degree of co morbidities, including

a) Anxiety disorders

b) Mood disorders

c) Personality disorders Phillips and McElroy [11].

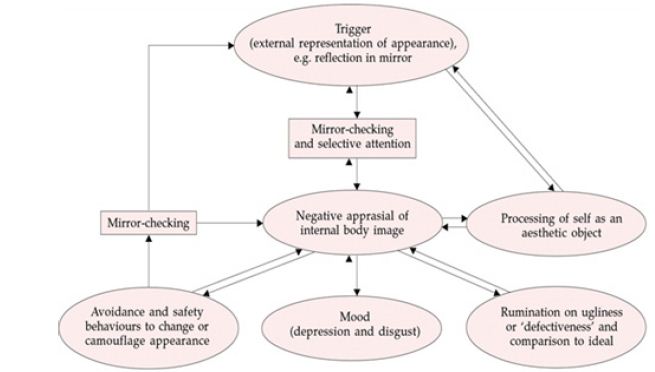

The literature consists largely of case reports and case series, with type of treatment and its frequency and duration which varies varying slightly from one case to another. Little is known about long-term outcomes of treatment. Following is a short review of treatment prospects in body dysmorphic disorder. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) model of BDD focuses on the experience of patients when they are alone (rather than in social situations, when their behavior is likely to follow a model similar to that of social phobia Clark and Wells [12]. The model begins with the trigger of an external representation of the individual’s appearance or body image, often in front of a mirror. he process of putting selective attention begins by focusing on specific aspects of the external representation (e.g. the reflection in the mirror) which leads to an increased awareness and an exaggeration of certain parts of the body and features.

As a result, the individual with BDD forms a distorted mental representation of the body image. This leads to a negative appraisal about one’s own appearance and comparisons of three different images-he external representation (usually in a mirror), the ideal body image and the distorted body image. The patient’s desire to see exactly how she or he looks is only reinforced by looking in the mirror, the longer the individual looks, the worse she or he feels and the more the belief of ugliness and defect are reinforced. There are four randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that have evaluated CBT for BDD against a wait list. These are all small studies that have demonstrated greater efficacy of CBT compared to a wait list over 12 to 22 sessions Rabiei et al. [13]; Rosen et al. [14]; Veale et al. [15]; Wilhelm et al. [16].

No RCTs have examined whether a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) can enhance outcome of CBT for BDD either in the short or long term. Four long-term naturalistic outcome studies of people with BDD with 12-month outcomes Fontenelle et al. [17]; Phillips et al. [18]. In these studies, full remission was defined as minimal or complete absence of BDD symptoms, and partial remission as meeting less than full DSM-IV criteria for at least 8 consecutive weeks. Phillips et al. [18] retrospectively assessed that at 1-year follow up, 24.7% of 95 participants had achieved full remission, while another 33.1% had experienced partial remission at the 6-month and/or 12-month follow-up. After 4 years, 58.2% of study subjects had achieved full remission, and another 25.6% had reached partial remission. Subjects who attained full or partial remission, 28.6% subsequently relapsed. However, all patients had received SSRI medication, only 21.7% had received CBT (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Credits: Veale (2001) Cognitive-behavioral therapy for body dimorphic disorder.

In a prospective by Phillips et al. [18], follow-up of 183 participants in which 9% achieved a complete remission and 21% reached partial remission at 1-year follow-up. There was an overall average probability of relapse of .15 in the study. Most patients had received psychotropic medication, only 16% was considered optimal and only 21.9% had received CBT, in which it was difficult to judge the quality. A follow-up report of Veale et al. [19], conducted an RCT to study if CBT had greater efficacy than anxiety management in BDD. The study revealed that about 50% made only limited gains with CBT, and continued to have a chronic condition. Cognitive behavioral therapy is considered the psychological treatment of choice for both OCD March et al. [20] and BDD Williams et al. [21].

A Meta-analysis of Williams et al. [21] on treatments for BDD revealed large effect sizes for CBT and supports its superiority over pharmacological treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. In a study, more than 30% of the participants abandon treatment, and asymptomatic criteria were rarely reached following CBT. One variable linked with poorer response to CBT in patients with BDD is overvalued ideation (OVI) Neziroglu et al. [22]. BDD patients have been found to show particularly high levels of OVI McKay et al. [23] which makes it an important variable to address in order to improve treatment options. Overall, long-term efficacy of CBT for BDD seems promising yet limited research evidences and high dropout rates of patients have led to less accurate appraisal of the therapy.

Inference based therapy (IBT) is a form of cognitive intervention which was initially developed for OCD with high overvalued ideation. In a research, IBT was shown to be as effective as CBT in treating OCD patients. It was found to be more effective than cognitive therapy in people with OCD with high obsession investment O’Connor et al. [24]. As BDD seems phenomenologically similar to OCD and also is characterized by high levels of OVI, IBT appears a viable treatment for clients with BDD. The reasoning process is hypothesized to be common to OCD and BDD and to lead to obsessions is termed inferential confusion O’Connor et al. [24]. Those whose reasoning processes are characterized by inferential confusion are shown to have a tendency to distrust their senses and to invest in remote or imaginary possibilities at the expense of reality.

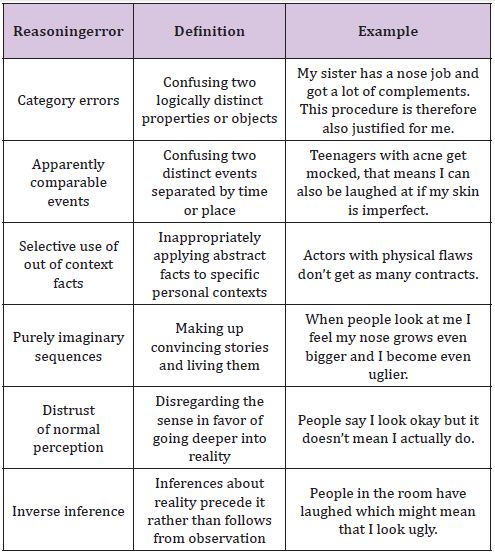

Table 1: Overview of reasoning errors in BDD.

The aim of IBT is to modify the reasoning narrative producing the doubt, and helping the person to return to the world of common sense perception. In IBT, obsessions are conceptualized as a twostep process. The person first arrives at one or more primary inferences through a subjective narrative (inferential confusion) which leads them to confuse reality in the here and now with remote possibilities. In BDD, primary inferences are often held with great conviction with overvalued beliefs. The primary inference is generally followed by one or more secondary inferences. Secondary inferences refer to negative anticipated consequences of primary inferences (Table 1).

Thirteen BDD participants, of whom 10 completed, underwent a 20-week IBT for BDD. Participants improved significantly throughout the course of therapy, with huge reduction in BDD and depressive symptoms. OVI also decreased over the course of therapy and was not found to be related to reduction in BDD symptoms. IBT has found to be effective in reducing the symptoms of BDD. Also, it helped in reducing depressive symptoms that often accompanies BDD. There are no RCT’s or rigorous studies that are done to evaluate the efficacy of IBT. The presence of limited literature suggests IBT to be a therapy modality that is promising alternative.

Exposure-based CBT: Like OCD, individuals with BDD appear to have “compulsions” and tend to engage in ritualistic behaviors, leading to reduction in anxiety symptoms. More precisely, these behaviors are conducted with the intention of hiding, examining, correcting, or looking for reassurance about one’s appearancerelated concerns. Other “compulsive” behaviors include comparing oneself to others, dieting, measuring the “flawed” body part, seeking a cure (e.g., cosmetic, dental, dermatological, etc.) for the perceived defect. In BDD, exposure helps the patient to learn that

(a) Fear that other people will notice and will respond negatively to their imagined physical defect are excessive and unrealistic, and

(b) Feelings of anxiety and embarrassment are temporary and tolerable.

Following exercises are incorporated into exposure for BDD:

a) Going out in public without makeup,

b) Enhancing an imagined defect using makeup, and

c) Wearing pants that reveal or accentuate certain parts of the body.

Gorbis [25] has reported success exposing patients to distorted images of themselves (i.e., using a curved mirror) while having them resist using a normal mirror to check on their body shape. In a review by Williams et al. [21], identified 9 studies of exposurebased CBT for BDD. The mean effect size across studies in which treatment involved only exposure response prevention (ERP) was 1.21, and that for studies of CBT which involved ERP was 1.78. These effect sizes are large and comparable to the effects observed with the use of ERP for OCD. Khemlani-Patel, Neziroglu and Mancusi [26] and Neziroglu, Khemlani-Pateland Santos [27] found that adding cognitive therapy to ERP did not significantly enhance the effects of ERP alone. The small sample size of this study notwithstanding, findings from the treatment literature suggest that ERP is efficacious in the treatment of BDD.

Compassion focused therapy (CFT): Another therapy that has proved its effectiveness in BDD is compassion focused therapy (CFT), an intervention was simply to practice creating a warm voice, as if talking to a friend, and really try to feel the impact of that kind voice. It turned out that many depressed patients struggled to do this or were resistant; or that ‘feelings of kindnesses started a grief process Gilbert & Irons [28]. Over subsequent years, CFT built on other aspects of compassion such as the capacity for empathy for distress, distress tolerance, and creation of genuine compassionate motivation to work with distress.

Generating alternative thoughts and most behavioral practices had to meet the compassion test ‘where the intervention (e.g., alternative thoughts) are experienced as helpful, kind, supportive and validating.’So CFT makes a big distinction between blaming and shaming and the processes by which we develop the courage to take responsibility for change and then engage the change processes all the time keeping an eye on the affinitive experience during the process of change. So a key message to someone with BDD is that the way their brain has been shaped is an evolutionary problem of being human and internal threats, and that BDD symptoms are designed to keep them safe from perceived social exclusion or rejection. This offers a different rationale for therapy. One may help the person realize how old and new brain create loops and how becoming more mindful of those loops and taking the compassionate but also rational evidence-based stance can help one breakout of those loops.

The focus in this approach is on communicating empathically that people are not to blame for their BDD and making sure the client has a good developmental understanding of the problem. In CFT it is important to work with these feelings of aloneness and separateness because they are symptomatic of a very dysfunctional affinitive system. These insights point to the kind of social environment and therapeutic relationship that needs to be created for a person with BDD who finds feeling safe difficult. It means not just appealing to the rational “new brain” to do exposure. It harnesses the new brain for a behavioral experiment to test out an alternative understanding of the problem and to reduce selffocused attention (which is the source of the threat).

This also means trying to prevent unnecessary activation of the threat system by one’s inner critic and the use of mindfulness and compassionate imagery practices to try to stimulate the compassionate pathways and to feel safe. The evidence base is of course still to be developed, particularly with well controlled trials. Further research is required to determine whether their outcomes can also be improved by adding modules such as compassion-focused therapy for body shame Veale & Gilbert [29]. Body dysmorphic disorder may be a condition that requires greater investment in both the treatment and maintenance compared to other common emotional disorders.

A comprehension of mental premise of body image preoccupations and the clinical presentation of BDD is vital in choice of appropriate therapeutic interventions. It becomes important to figure out that people with BDD may need knowledge into the psychological aspect of BDD. Information and a high index of doubt and suspiciousness are important to analyze the symptoms and make the diagnosis of BDD, and clinicians ought to embrace a multidisciplinary approach in therapy, incorporating cooperation among those in psychiatry, dermatology, restorative surgery, family rehearse, and different required specialties. Treatment with CBT ought to be considered in people with BDD because of its established results. Further researches are required to establish more appropriate and annualized approach of therapy to treat BDD (especially the delusional variant of BDD).