Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Hafizur Rahman*

Received: August 04, 2017; Published: August 10, 2017

Corresponding author: Hafizur Rahman, Professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Sikkim Manipal Institute of Medical Sciences, 5th Mile, Tadong, Gangtok,Sikkim-737102, India

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2017.01.000267

Preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome, both disorders unique to pregnancy, remain a major cause of maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity worldwide. It is the most common medical disorder complicating pregnancy. In both of these disorders, the liver is a major target with often devastating consequences. The pathogenesis of hepatic damage in cases of severe preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome is not well understood. Diagnosis of HELLP syndrome is heavily relied upon laboratory investigation. In the management, first priority is to assess and stabilize the maternal condition, particularly coagulation abnormalities followed by evaluation of fetal well‑being and finally, a decision must be made as to whether or not immediate delivery is indicated. Women with a prior history of HELLP syndrome carry an increased risk of at least 20% (range 16%-52%) risk of recurrence of some form of hypertension, so future pregnancy counseling and follow up is essential.

Keywords: Preeclampsia; HELLP Syndrome; Eclampsia; Corticosteroids

Abbreviations: Hemolysis; EL: Elevated Liver Enzymes, LP: Low Platelets; SIRS: Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome; LDH: Lactate DeHydrogenase; DIC: Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation; TTP: Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura; HUS: Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome; AFLP: Acute Fatty Liver of Pregnancy

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy are a dreaded disease for both the mother and the fetus. Preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome, both disorders unique to pregnancy, remain a major cause of maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity worldwide. It is the most common medical disorder complicating pregnancy, affecting 7 to 15% of all women. As high as 22% perinatal deaths and 30% of maternal deaths in developed countries are because of preeclampsia. The situation is far by worse in developing countries because of low antenatal turn up, delayed reporting and inefficient management in most of the heath setups [1]. Credit for formally consolidating the concept and creating the acronym of HELLP (H = hemolysis, EL = elevated liver enzymes and LP = low platelets) goes to Louis Weinstein who in 1982 reported a group of 29 pregnant patients he considered to have a distinct subset of severe preeclampsia/eclampsia. There is considerable disagreement in the medical literature regarding the terminology, incidence, diagnosis, and management of the HELLP syndrome. During the past 15 years, numerous retrospective and observational studies as well as few randomized trials have been published in an attempt to refine the diagnostic criteria for this syndrome, to identify risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcome, and to reduce maternal and perinatal outcomes in women with this syndrome. Despite this recent literature, the diagnosis, management, and pregnancy outcome of HELLP syndrome remain controversial [2].

HELLP syndrome usually develops suddenly during pregnancy (27-37 weeks’ gestation) or in the immediate puerperium [3-7]. As a form of severe preeclampsia, it likely has its origins in aberrant placental development, function, and ischemia-producing oxidative stress, which triggers the release of factor(s) that systematically injure the endothelium via activation of platelets, vasoconstrictors, and loss of normal pregnancy vascular relaxation. Although most patients with HELLP syndrome eventually exhibit hypertension and proteinuria, these 2 major signs of severe preeclampsia bear no consistent relationship with laboratory parameters of the underlying vasculopathy. A variety of symptoms can be elicited that are ambiguous, subtle, and focused primarily on the gastrointestinal-hepatic systems [4-7].

The central place that the liver occupies in the disorder of HELLP syndrome is an important clue to pathogenesis. The similarity between HELLP syndrome and systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) has been emphasized by several researchers. The perturbations present in patients who have HELLP syndrome develop may be additive to, or altered by, the path physiology leading to preeclampsia in general [3].

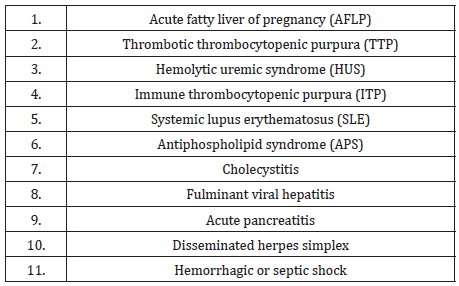

Patients with preeclampsia-eclampsia and HELLP syndrome may present with various signs and symptoms, none of which are diagnostic. Pregnant women usually present in their third trimester with complaints of malaise (90%), epigastric or right upper quadrant pain (90%), nausea or vomiting (50%), or nonspecific viral like symptoms. Although, majority of these patients present in the third trimester, it is not uncommon to see these cases in the later part of second trimester, or in the postpartum period [1]. However, these clinical features are also common presentation for several other benign and serious pregnancy and non pregnancy related conditions (Table 1) [8]. For this reason, pregnant women with any concerning symptoms should undergo a diagnostic work‑up including a complete blood count, platelet count, liver evaluation, and urine dipstick for protein irrespective of their blood pressure. Presence of abnormal urine dipstick for protein should be followed by quantitative evaluation for protein in a 24 hour urine specimen [1].

table 1: Differential diagnosis in women with HELLP Syndrome.

Pregnant women usually present in their third trimester with systemic hypertension, proteinuria, and peripheral edema. Patients may present with increased weight gain, headache and visual disturbances, and gastric complaints of nausea and vomiting. The severity of preeclampsia is based on the presence of cerebral disturbances, proteinuria more than 5 gram/24 hours, or evidence of thrombocytopenia or hemolysis. Hepatic involvement occurs in approximately 10% of severe preeclampsia cases. It is not uncommon that these women may have transient liver enzyme elevations without clinical signs of pain [1].

Abdominal pain is common and may be present in about 50% of the patients. Abdominal pain is usually encountered in the right upper quadrant, epigastric or substernal region and often associated with laboratory abnormalities defining HELLP syndrome. Abdominal pain is generally absent in other disorders unique to pregnancy such as cholestasis of pregnancy and hyperemesis of pregnancy; however it is frequently encountered in HELLP and AFLP. Although HELLP syndrome may have symptoms similar to preeclampsia and is one of the criteria that can define severe preeclampsia, it can develop in women who might not have any other signs or symptoms of preeclampsia. Preeclampsia is not a prerequisite for HELLP syndrome and hypertension, if present, does not have to be severe. Severe hypertension defined as systolic blood pressure ≥160 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure ≥110 mm Hg, is not a constant or even a frequent finding in HELLP syndrome [1,3].

Hemolysis, defined as the presence of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, is the hallmark of the triad of HELLP syndrome [9]. The classical findings of microangiopathic hemolysis include significant drop in hemoglobin levels, elevated serum indirect bilirubin, low serum haptoglobin levels, elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels and abnormal peripheral smear (schistocytes, burr cells, echinocytes). The same ambiguity exists with the use of abnormal liver function tests for defining HELLP syndrome. There is no consensus regarding the degree of liver enzyme elevation that is used for diagnosing HELLP syndrome [10]. Low platelet count is another abnormality required to make a diagnosis of HELLP syndrome. However, there are no defining criteria for low platelet count. Adding to this confusion, HELLP syndrome shares many clinical and laboratory characteristics with equally serious conditions like systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) and acute fatty liver of pregnancy (AFLP) and can be easily confused with these conditions [1].

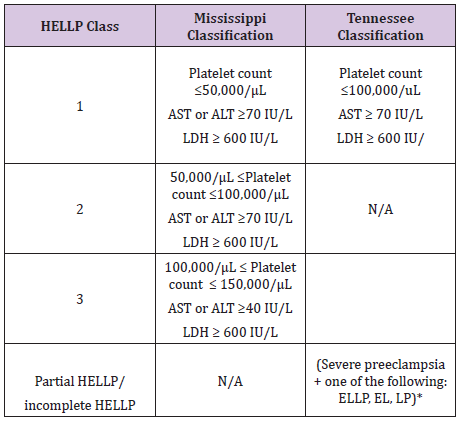

Table 2: Main diagnostic criteria and classification systems of HELLP Syndrome.

*ELLP-Absence of hemolysis; EL-elevated liver functions; LP-low platelets.

Diagnosis of HELLP syndrome is heavily relied upon laboratory investigation. Hence the differential diagnosis for this condition should include a varying consideration including hepatic, hematological and other systemic conditions. In trying to differentiate it from acute fatty liver of pregnancy which occurs in the third trimester of pregnancy, a common clinical observation is that the liver dysfunction is more pronounced in the later with coagulopathy, hypoglycemia and renal failure are present. The coagulopathy in AFLP is due to acute liver failure, whereas in HELLP syndrome coagulopathy develops as a part of the DIC syndrome with microangiopathic hemolytic anemia [1]. Two major diagnostic classification systems are currently used for the classification of HELLP syndrome (Table 2) [11,12]. In the Tennessee classification system; a diagnosis of the complete form of HELLP syndrome requires the presence of all three major components, whereas partial or incomplete HELLP syndrome consists of only one or two elements of the triad. The presence of an abnormal peripheral smear (e.g., microangioplastic anemia with schistocytosis), thrombocytopenia, and elevated levels of AST, ALT, bilirubin, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) is diagnostic. The Mississippi classification system has been proposed for assessment of the severity of the pathologic process, with class 1 HELLP syndrome having a worse prognosis and longer hospital stay than either class 2 or class 3. This classification system is based on the degree of thrombocytopenia and the extent of elevation in transaminase and LDH levels, as shown in (Table 2). The platelet count and serum LDH levels are found not only to be moderately predictive of the severity of the disease but also to indicate the speed of recovery [11,12].

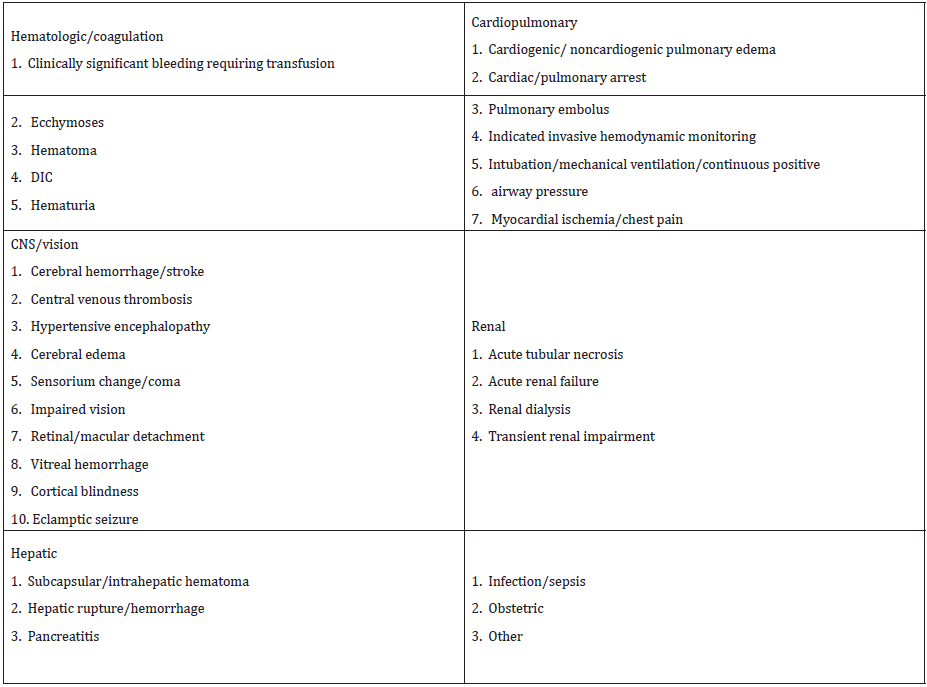

The development of HELLP syndrome places the pregnant patient at significant risk for morbidity and mortality. Morbidity (Table 3) is categorized by major organ system(s) affected and is stratified by extent of disease using the Mississippi classification system [3]. Cesarean delivery has been performed more often for patients with class 1 HELLP syndrome (61%) than class 2 (57%), class 3 (53%), or non-HELLP severe preeclampsia (48%).Mode of delivery is strongly influenced by gestational age, maternalfetal status, class of disease, and corticosteroid utilization. Overall abdominal delivery is associated with a doubling of maternal morbidity (cardiopulmonary, hematologic-coagulation, and infectious) compared with vaginal delivery. Most deaths in patients with HELLP syndrome occur with class 1 disease (60%), and neurologic abnormality due mostly to cerebral hemorrhage/stroke is the most common system involved [13].

Table 3:Significant maternal morbidity in HELLP Syndrome.

Perinatal morbidity and mortality are substantially higher in pregnancies with severe preeclampsia complicated by HELLP syndrome, primarily because of required preterm delivery. Fetal growth restriction and fetal distress after 32 weeks also may be more frequent. Although neonatal deaths and perinatal mortality rates tend to be progressively higher in parallel with increasingly severity of disease, outcomes are primarily related to gestational age at delivery and not to disease status. Continuation of HELLP syndrome pregnancy beyond 26 weeks and the time necessary for steroid enhancement of fetal lung maturation increases the risk of stillbirth substantially. Long term prognosis for the children of mothers with HELLP syndrome is comparable to controls matched for gestational age [3,13].

Patients who are remote from term should be referred to a tertiary care center [1]. The first priority is to assess and stabilize the maternal condition, particularly coagulation abnormalities. The next step is in the evaluation of fetal well‑being and gestational age. Finally, a decision must be made as to whether or not immediate delivery is indicated. There is a consensus of opinion that prompt delivery is indicated if the syndrome develops after 34 weeks of gestation or earlier if there is multi-organ dysfunction, DIC, liver infarction or hemorrhage, renal failure, suspected abruption of placenta, or non reassuring fetal status [1,14].

There is significant disagreement regarding management of women with HELLP syndrome before 34 weeks of gestation. Fetal lung maturity is not achieved by this time. Some authors recommend prolonging pregnancy until 34 weeks of gestation or until the development of maternal or fetal indications for delivery. Although it appears that expectant management may be beneficial, the overall perinatal outcome did not seem to improve when compared with cases of similar gestational age who were delivered within 48 hours after the diagnosis of HELLP syndrome [1].

The clinical course of HELLP is one of progressive deterioration of the maternal and fetal conditions, and the selection of cases to delay delivery should be rigorous. Patients selected for delayed delivery will require administration of magnesium sulfate, steroids (Betamethasone 12mg IM two doses 24 hour or 12 hour apart) for prevention of IVH and RDH. Delivery should be accomplished within 24 hours following the last dose of steroids [15]. The use of corticosteroids in the management of HELLP syndrome remains controversial. In a Cochran review of randomized controlled trials comparing any corticosteroid with placebo, no treatment, or other drug; or comparing one corticosteroid with another corticosteroid or dosage in women with HELLP syndrome. There was no difference in the risk of maternal death or severe maternal morbidity or perinatal/infant death. The only clear effect of treatment on individual outcomes was improved platelet count. Authors concluded that there was no clear evidence of any effect of corticosteroids on substantive clinical outcomes [16]. The National institute of Clinical excellence (NICE) and Royal college of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) guidelines recommends not to use corticosteroids for management of HELLP Syndrome [14].

Prevention of severe systolic hypertension (>160 mm Hg) is paramount; recommendations to maintain systolic pressures under 150 mm Hg and diastolic pressures under 100 mm Hg are reasonable goals. Labetolol, hydralazine, or nifedipine are the preferred agents for treatment of acute hypertension [1]. Maternalfetal status, gestational age, presence of labor, cervical Bishop Score, prior maternal obstetric history, and response to aggressive corticosteroids all impact management of the patient with a preterm viable fetus and HELLP syndrome. Immediate cesarean delivery is not generally indicated or recommended; vaginal or cesarean delivery after 24 to 48 hours of corticosteroids are better options to achieve maximal maternal and fetal benefit. Nevertheless, because vaginal delivery rates with HELLP syndrome are below 50% for gestations less than 30 weeks, some authors advocates elective cesarean delivery for all women diagnosed with HELLP syndrome at a gestation age less than 30 weeks when spontaneous labor is not present and the Bishop score is less than 5. A patient with a low Bishop score in association with fetal growth restriction and/ or oligohydramnios may not be a good candidate for trial of labor. Otherwise, vaginal delivery is attempted in patients in active labor less than 30 weeks with ruptured membranes or with a Bishop score 5 or more in the absence of obstetric contraindications. Once the 30-week gestational age threshold is reached, an attempt at vaginal delivery is usually recommended. Epidural or spinal anesthesia is the preferred anesthetic for patients with preeclampsia. Approximately 50% of patients with HELLP syndrome can be candidates for regional anesthesia during a trial of labor using a threshold of 100,000/μL platelets. In these circumstances, the decision of abdominal versus vaginal delivery becomes more of an obstetric issue rather than a response to a rapidly worsening maternal-fetal condition [3].

Women with a prior history of HELLP syndrome carry an increased risk of at least 20% (range 16%-52%) that some form of gestational hypertension will recur in a subsequent gestation. The rate of recurrent HELLP syndrome itself varies between 2% and 19% depending on the population studied, gestational age at onset, whether there is concurrent vascular disease of any type, and very likely the unique genetic profile of the individual patient, her partner, and her progeny. To date, anything other than close monitoring of subsequent pregnancies for problems of prematurity and preeclampsia (preterm labor, bleeding, fetal growth restriction) has not been superceded by specific testing or augmented by effective preventative measures [3].