Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Thomas W Miller*1, Deborah Burton2, Christina Busse2, Robert F Kraus3 and Thomas W Miller4

Received: July 27, 2017; Published: August 07, 2017

Corresponding author: Thomas W Miller, Professor Emeritus & Senior Research Scientist, University of Connecticut, USA

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2017.01.000258

Utilizing wearable SMART biomedical technology has a place in contemporary health care interventions. There is an emerging research literature in support of an effective intervention methodology for improved health and well-being as measured by health and wellness markers utilizing a wearable SMART technology. Current limitations along with future directions are discussed. Health care professionals may benefit from the utilization of wearable SMART technology as an adjunct when treating both patients who experience anxiety related to their medical conditions.

Keywords: SMART Wearable Technology; E-Health; Dialectic Behavior Therapy

Abbreviations: SMART: Self-Monitoring Analysis and Reporting Technology, DBT: Dialectical Behavior Therapy; PDA: Personal Digital Assistant

Healthcare practice utilizing technology- is transitioning in the delivery of health care. Health care professionals today require an approach that addresses both physical and mental health issues involving intervention models that require a limited number of appointments that demonstrate measureable improvements in the current managed care environment. Wearable SMART technology provides a potential adjunct for use in assessing the therapeutic progress of some behavioral activities of patients. SMART stands for Self-Monitoring Analysis and Reporting Technology.

Mochari-Greenberger [1] DeLucia [2] Steinhubl [3] are among current researchers who have identified the value and benefits of wearable technology for various populations raising the question as to whether there may be beneficial use with individuals in treatment for health related conditions. Wearable SMART technology employs digital technologies to collect health data from individuals in one location, such as a patient’s home, and electronically transmitting the information to healthcare providers in a different location for assessment, monitoring and compliance [4,5].

Contemporary e-health [6] allows health care professionals to evaluate, diagnose and treat patients in remote locations using telecommunications technology. Smart wearable technologies are viewed as noninvasive digital technologies. SMART technology use as an adjunct clinical therapeutic model in healthcare has been theobject of recent psychotherapeutic interventions and is receiving greater attention in the literature. There are within the tele health literature relevant research studies which contribute to the current level of evidence supporting SMART technologies role in health therapeutic interventions [3,7]. Chan, Estèveet al. [8] examined the use of SMART wearable systems in a broad area of health and wellness interventions. The results of their research concluded that advances in SMART technologies and subsequent SMART devices, ranging from sensors and actuators to multimedia devices, support complex healthcare applications and enable low-cost wearable, non-invasive alternatives for continuous monitoring of health bio marker, activity, mobility, mental status, both indoors and outdoors.

There is a patient population that includes those individuals enrolled in health-related counseling and therapy where the intervention is consistent with the cited definition of telemedicine and remote patient monitoring was employed using noninvasive digital technology for physical and psychological conditions. Such interventions have included interventions based on technology, using devices including smart phones and PDA devices. Apersonal digital assistant (PDA) is a handheld device that combines computing, telephone/fax, Internet and networking features. A typical PDA can function as a cellular phone, fax sender, web browser and personal organizer. PDAs may also be referred to as a palmtop, hand-held computer or pocket computer. There is associated software used to transmit patient data to the patient’s health care professional, including multiple health care providers and researchers.

Such wearable devices worn or placed on one’s body record a number of bio-physiological markers including such things as respiratory rate sensors, sleep and waking patterns of activity and blood pressure. There are also biosensor devices for recording data from biological or chemical reactions such as pulse oximeters or spirometers. The benefit of remote activity monitoring has been the object of recent research. This has included healthy adults [9] as well as in populations experiencing multiple medical and psychiatric diagnoses, chronic disease management conditions, treatment adherence, patient outcomes and compliance with prescribed treatment plans [1]. In treating the whole person, mental health counselors may be called upon to work with medical and allied health professionals in providing effective patient care.

Use of wearable remote monitoring for physical health conditions have included autoimmune disorders [10]; obesity [11,12]; psychiatric disorders [13], type 1 diabetes and glycemic control [13,14]; pulmonary rehabilitation [15]; asthma [16], cancer [17]; dementia and cognitive decline [5]; weight management and obesity [11]. There have been a number of studies through the Department of Veterans Affairs targeting specific populations including health informatics, home telehealth, and disease management in support of the care of veteran patients with chronic conditions [18] (Wood, Miller 2012). More specifically, noninvasive technologies are now commonly being integrated into disease management strategies to provide additional patient information, with the goal of improving healthcare decision-making. Digital technologies are continually being adopted as an additional method for healthcare systems to increase patient contact and augment the practice of psychotherapeutic care and treatment.

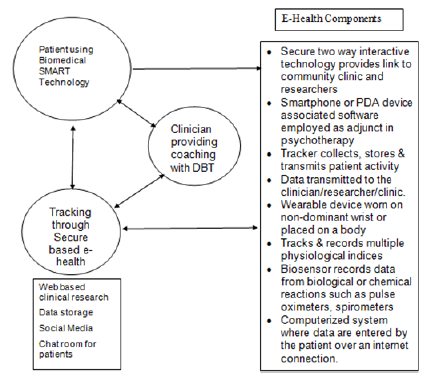

SMART technologies measurable data to assess compliance and sharing health data with remotely based clinical experts for consultation, saving time and expense for practitioners and patients, and actively managing treatments for those with chronic conditions. The accuracy, validity and reliability of trackers has been addressed by researchers with favorable results [19] Health data are typically transmitted to healthcare professionals in facilities such as monitoring centers in primary care settings, hospitals and intensive care units, skilled nursing facilities, and centralized management programs, among others. Figure 1 provides a schematic for this model of healthcare delivery.

Summarized in (Figure 1) are the core elements of SMART technology available for use with mental health interventions. Patient motivation is a critical element in therapeutic change and can best be measured by patient commitment and compliance with prescribed treatment interventions. It assumes an understanding of patient’s readiness to change [20] and the importance of working with a motivated patient using SMART technology as an adjunct to counseling and psychotherapy strategy. An evidence based contemporary counseling approach that may provide valuable treatment outcomes with some health related interventions is a Dialectical Behavior Therapy [21] model and utilizing available SMART technology for monitoring compliance and behavior changes with a patient. Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) combines both cognitive and behavioral techniques for treating individuals. Using a modified DBT model including individual health counseling may offer the skills and provide measurable data through smart phone consultation.

Figure 1: A Model for SMART Biomedical Technology in Patient Care.

Contemporary web culture users are ready for the uses of these biomedical technological advances in monitoring heal care [22]. There is growing evidence that the utility and benefits of smart technology tracking is being established and beneficial to mental health interventions [4,10,23,24]. Wearable devices are always on and accessible and their ability to help monitor, sort, and filter biomedical information is becoming more closely connected to our daily lives. Health promotion science will benefit from the use of such biomedical technology [25,26]. Wearable devices can be beneficial to assisting mental health counselors in monitoring effective behavioral changes of patients in the delivery of health care in the 21st century. Adapted from: Miller TW, Wood J (2012) Tele practice: A 21st Century Model of Health Care Delivery.