Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Bi Xia Ngooi1* and Tanya Packer2

Received: July 12, 2017; Published: July 19, 2017

Corresponding author: Bi Xia Ngooi, National University Hospital, Rehabilitation Centre, Level 1 Main Building, 5 Lower Kent Ridge Road, Singapore 119074

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2017.01.000215

Objective: With evidence that patient activation is alterable and can be increased in adults with chronic conditions [1], interventions targeting activation it is growing. However, little is known about what constitutes a patient activation intervention (PAI). Therefore, this integrative review aims to explore the components of PAI in existing literature.

Methods: An integrative review based on updated methodology proposed by Whittemore and Knafl [2], was used to examine the components of PAIs. A literature search was conducted using CINAHL, PubMed, PsycINFO, and PsycARTICLES.

Results: A total of 10 peer-reviewed articles were identified. All articles originated from USA, with seven based in community health services. There are two main types of PAI found in this review. Half of the studies focused specifically on physician-patient relationships, with a narrower definition of activation. The others focused on self-management, facilitating behaviour changes and tailoring interventions according to activation levels.

Conclusion: There are various format and contents in the ten studies, with interventions focusing on physician-patient communication being the most widely replicated format.

Practice Implications: While there are some promising results, more studies are needed to examine components of PAI that works and the long-term effectiveness.

Abbreviations: PAI: Patient Activation Intervention; CCM: Chronic Care Model; PAM: Patient Activation Measure; RQP: Right Question Project; CAD: Coronary Artery Disease; CHF: Chronic Heart Failure; COPD: Congestive Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

The burden of chronic diseases is escalating rapidly worldwide. According to the World Health Organization [3], 68% of global deaths in 2012 were due to chronic diseases, contributing significantly to the leading causes of burden of disease. The Chronic Care Model (CCM) [4] is a widely adopted approach to inform chronic diseases practices. Although evidence suggests that such practices generally improve quality of care and outcomes for patients with chronic diseases [5], it has been argued that the lack of effective patient activation strategies has limited the full implementation of this model [6].

Patient activation defined as one having knowledge to manage their condition and maintain functioning and prevent health declines; skills and behavioral repertoire to manage their condition, abilities to collaborate with their health providers, maintain their health functioning, and access appropriate and high-quality care [7], can significantly improve health outcomes in chronic diseases care [1,8,9].

Hibbard and colleagues [7] developed the Patient Activation Measure (PAM) to assess knowledge, skills and confidence in managing health [7,10]. Research demonstrated that higher PAM scores are associated with more satisfaction with services [9], more engagement in care and self-management behaviours [7,9], and improved health outcomes [9,11]. With evidence that patient activation is alterable and can be increased in adults with chronic conditions [1], interventions targeting activation it is growing. However, little is known about what constitutes a patient activation intervention (PAI). Therefore, this integrative review aims to explore the components of PAI in existing literature. The specific objectives are to examine

i. The intervention format

ii. Intervention contents

iii. Training for providers/facilitators.

An integrative review based on updated methodology proposed by Whittemore and Knafl [2], was used to examine the components of PAIs. A literature search was conducted using CINAHL, PubMed, PsycINFO, and Psyc ARTICLES. The specific search terms used were: “patient activation” AND interven(*) or treat(*) in PubMed, (patient N3 activat*) AND interven(*) or treat(*) in the other 3 databases. The search resulted in 581 references. Of these 139 were duplicates, reducing the total to 442 articles. Given the research aims to be examined in this integrative review, specific inclusion criteria were used to ensure the inclusion and review of all relevant intervention studies.

Studies included met the following criteria:

i. Implementation of a non-pharmacological intervention to improve patient activation (as stated by the authors)

ii. Measure of patient activation

iii. Written reports in English. Studies were excluded if the focus of intervention was not stated to be patient activation, or if the focus was on relationships with patient activation or measurement of patient activation evaluation. 10 peerreviewed studies met the criteria and were included in this review.

A total of 10 peer-reviewed articles were identified. All articles originated from USA, with seven based in community health services. Two authors (Alegria and Deen) had two articles each included in this review. Alegria and colleagues reported on a pilot version in 2008 and a refined version in 2014. Deen and colleagues reported on the same intervention used in different study design in both the 2011 and 2012 paper. This same intervention was also adopted in the paper by Maranda, et al. [12]. It was of interest to note that all the above mentioned interventions originated from the Right Question Project (RQP). All the other interventions were independent studies.

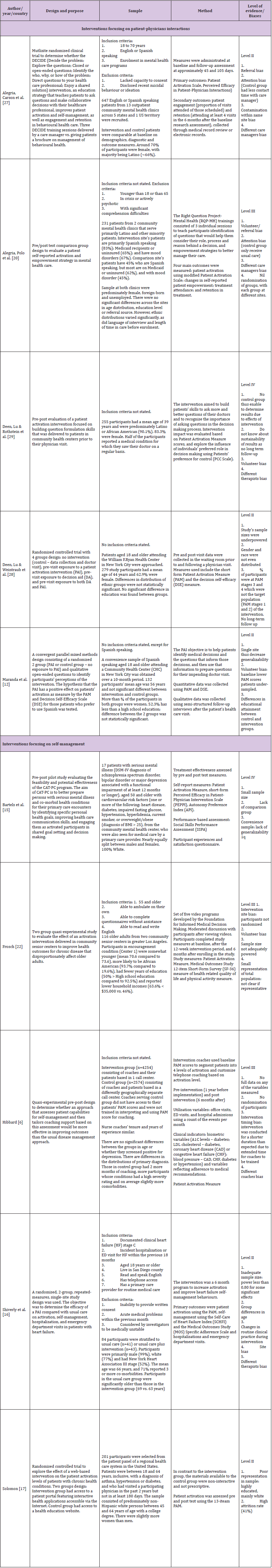

All papers were published in peer-reviewed journals. Due to the small number of articles found in this review, none were excluded. The articles were reviewed for quality of evidence as defined by Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt [13]. The level of evidence, study limitations and biases were presented in (Table 1).

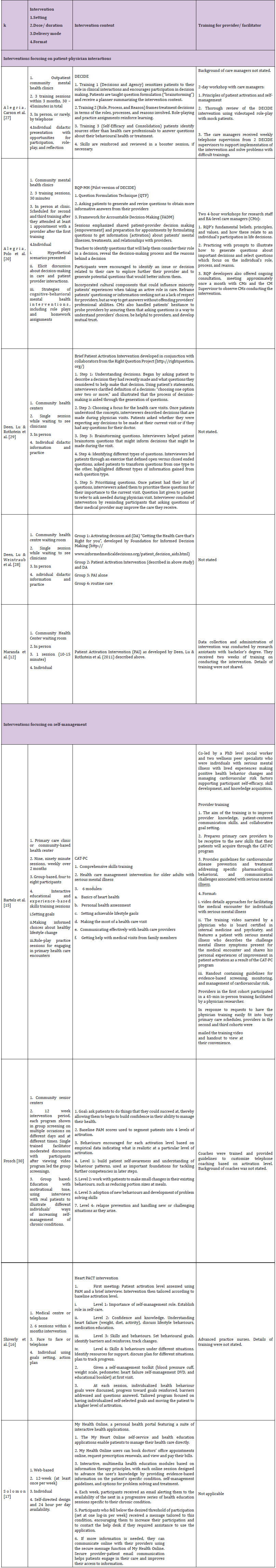

Articles meeting the criteria for inclusion were organized in subgroups by the type of intervention focus to facilitate comparison of design across similar interventions. Sources were described based on the following data elements that were extracted: author/ year, purpose and design, sample and method (Table 1). Theory was excluded from the table as none of the studies stated any theory explicitly. Findings of the components of PAI in the areas of setting, delivery mode, dose/duration, format, contents, and training for providers/facilitators were displayed in (Table 2). These are crucial components that clinicians have to consider when designing an intervention, thus identifying these elements allow comparison and critique of the studies, noting findings relevant to a PAI.

Table 1: Design of included studies.

Table 2: Components of Patient Activation Interventions.

The 10 studies represented a total of 8,787 study participants, mainly being older adults. Study sample sizes ranged from 17- 6828 participants. Gender was reported in all of the studies; and a slight majority was women (~54%). All studies were done in USA, with eight studies reporting ethnic groups which were mainly White, Latino, African and others. Given the homogeneity of studies from the same country, generalizability of findings based on these demographics characteristics is limited.

Seven of the studies recruited participants from community centres, with the rest being telephone coaching, web-based and medical centre. This may reflect a slant towards community care which looks after healthier adults with milder chronic diseases. This can also be a reflection of evidence showing that patient selfmanagement was particularly effective in community gathering places such as community groups [14]. However, more is needed to balance the uneven service provision and design interventions aiming to engage known hard-to-reach groups.

Three studies targeted participants with mental illness, with one specifically on mental illness and cardiovascular risk due to the elevated burden of cardiovascular risk factors among people with serious mental illness [15]. Shively, Gardetto, & Kodiath et al. [16] focused specifically on chronic heart failure. Four studies did not state the diagnosis while the other two targeted a range of chronic conditions such as asthma, coronary artery disease (CAD), chronic heart failure (CHF), congestive obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and diabetes in Hibbard, Greene & Tusler [1] and asthma, diabetes, hypertension in Solomon [17]. It is unclear if there is a need to be disease specific or generic programs as there are both formats presented in this review. Even though Hibbard & Gilburt [18] reported that activation is an underlying concept of human behaviour and is not disease-specific, chronic disease management research showed a preference for disease-specific programs [19]. This is because successful chronic disease management programs tend to have the ability to enhance chronic disease management self-efficacy, which leads to self-management behaviour change, and develops as a result of programs targeting specific diseases and behaviours [14]. Future research may be needed to investigate if these results in chronic disease management programs apply the same to PAI, thus indicating the effectiveness of disease-specific versus generic programs.

There are two main types of PAI found in this review. Half of the studies focused specifically on physician-patient relationships, with a narrower definition of activation being “developing experience with question formulation and building informationseeking skills that results in increased collaboration with the health care provider” [20]. Interventions that focused in this area see patient activation as engaging patients in their own care which is a strategy to improve self-management of chronic diseases [21]. One method is for patients to ask questions during physician visits. They are mainly short individual intervention (1-3 sessions) just prior to physician’s visits, focusing on facilitating patients to think of appropriate questions to ask physician.

Interestingly, even though physicians are part of the therapeutic relationship, none of the five interventions that focused on physician-patient communication included physicians training. Only one out of the ten studies in the whole review included physicians in the intervention [15]. In this study, challenges to include a brief in-person training of the physicians were reported, with the main reason being “busy physician schedules”. This may reflect physicians’ lack of receptiveness in improving their communication as a review on doctor-patient communication reflected that physicians tend to overestimate their abilities in communication [22]. This is despite literature consistently demonstrating physician’s communication and interpersonal skills as a central function in building a therapeutic patient-physician relationship which in turn facilitates the delivery of high quality health care [23,24]. Physicians who discourage patients from voicing their needs and concerns can deter patients from asserting their role in health care and may be unable to achieve their health goals [25]. As Fong & Longnecker [22] stated, physicians are not born with excellent communication skills and training has been found to improve physician-patient communication (Harms, Young, Amsler, Zettler, Scheidegger & Kindler, 2004; Bensing & Sluijs, 1985). Therefore, for future interventions in this area, one will have to consider communication training for physicians to truly improve physician-patient communication. There is also limited information on training for providers/ facilitators provided by the authors in this review.

While the current interventions are useful as brief and scalable approaches for practical considerations, they may not be closely align with research on strategies to improve patient engagement and activation. A review by Haywood [26] found that promising approaches consisted of patient coaching, feedback of patientreported outcome measures and communication skills training for providers. On the other hand, this form of intervention has been the one replicated by three independent research teams over five studies, the most widely replicated format and contents among this review. However, limitations have been recognised by various authors, such as without greater health care professional receptivity to activated patients, contributions to enhance patient activation and self-management may be limited [27] and study design limitations limiting firm conclusions on the effectiveness [28,29]. Future studies will be needed to demonstrate the effectiveness of this brief PAI and to consider the importance of both patients and physicians in promoting patient activation, as well as aligning with research findings on strategies to promote patient engagement and activation.

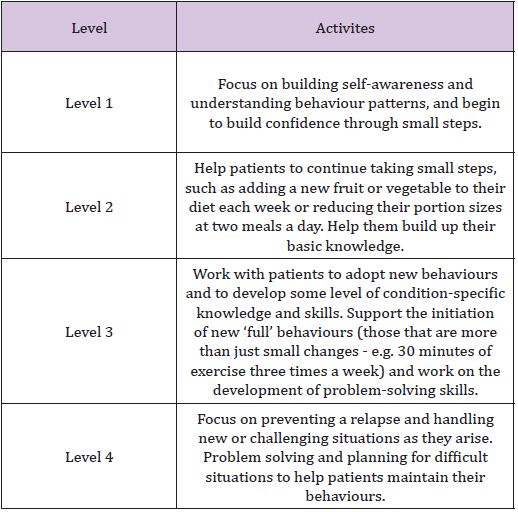

For the studies focusing on self-management, duration of interventions tend to be longer, ranging from nine weeks to six months. Two of the studies tailored the self-management intervention according to patient’s activation level while the rest worked on behavioural changes. For those that tailored interventions to patient’s activation level, the theory is similar to graded errorless learning in that patients who are less activated should be encouraged to take suitable small steps where they are likely to experience success. Experiencing success can motivate them to continue to build skills and confidence needed for selfmanagement [18]. These approaches recognised the different needs of patients in different activation levels and thus deliver care suitable for each level to maximise outcomes (Table 3).

Table 3: Components of Patient Activation Interventions.

For the other three studies, they each have their unique format and contents. Frosch [30] intervention assumption was that repeated exposure to the message that active self-management would improve chronic disease outcomes would lead to greater patient activation. However, given that literature has shown education-based interventions to be not sufficient by themselves to prompt behavioural changes and self-management [31], it is likely that vicarious learning and social persuasion in the group setting may have contributed to greater patient activation.

Solomon [17] study is the only web-based format and utilised intervention designed for enhancing self-management to investigate the effects on patient activation. Bartels [15] had an extended form of physician-patient communication intervention focusing on skills training for both patients and physicians, and adding on education and lifestyle goals setting. This intervention appears to be most closely aligned to components and strategies that work in both selfmanagement and patient activation literature, for example, group format, problem solving, skill building and communication training for providers. Although this is only a pilot study, the robust design of the intervention looks to be promising.

Even though chronic disease management literature has suggested the benefits of group-based intervention [14,32,33] only two out of the ten interventions adopted a group-based method. This may be due to resources constraints for the timelimited interventions of those that focused on patient-physician communication. Another consideration could be the emphasis on tailoring interventions to each individual. While the two types of PAI have different focus, the common factors include development of skills and building confidence. This is based on the theory in patient activation literature that many patients are ineffective or do not engage in self-management roles due to a lack of necessary skills or confidence [18]. As patients’ activation increase, they gain a greater sense of self-efficacy and control over their health, and become more empowered to take action [18]. Another common factor is the focus on encouraging individual to make choices and to self-initiate behaviours. This facilitated gaining of problem-solving skills needed in self-management of chronic diseases [34].

There are two main types of “Patient Activation Intervention” that are emerging in the literature. One focused on physicianpatient communication while another incorporated patient activation into behavioural changes. There are various format and contents in the ten studies, with interventions focusing on physician-patient communication being the most widely replicated format. While there are some promising results, more studies are needed to examine components of PAI that works and the long-term effectiveness. Some specific areas for future studies can include the following:

i. In other countries other than USA

ii. Interventions for known hard-to-engage groups

iii. Comparing effectiveness between disease-specific and generic PAI

iv. Interventions including training for attending physicians and/or healthcare professionals

v. Group-based PAI

vi. Long term effectiveness of the brief PAI focusing on physician-patient communication.

Brief PAI focusing on physician-patient relationships, should consider patient coaching, feedback of patient-reported outcome measures and communication skills training for providers. For the studies focusing on self-management, tailoring the selfmanagement intervention according to patient’s activation level and facilitating behavioural changes are the common components. However, more studies are needed to investigate components that work.