Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Raul M Vintimilla*, James R Hall, Leigh A Johnson and Sid EO Bryant

Received: July 12, 2018; Published: July 23, 2018

*Corresponding author: Raul Vintimilla, Department of Pharmacology and Neuroscience, University of North Texas Health Science Center, 3500 Camp Bowie Blvd., Fort Worth, Texas 76107

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2018.07.001462

Objective: Hypertension is a modifiable multifactorial risk factor that has been associated with cognitive impairment. The current study investigated the relationship between blood pressure levels and executive function in older Mexican Americans.

Methods: Data from 349 cognitively normal participants from the Health and Aging Brain Study among Latino Elders were analyzed to compare executive function status in those with and without a diagnosis of hypertension. Diagnosis of hypertension were based in self-report, medication status, and examination results. Executive function was assessed with Trails B education adjusted scale scores. Diabetes, dyslipidemia, and abdominal obesity were also entered in the models with age as a covariate.

Results: Both Males and females with a diagnosis of hypertension had significantly worse performance on Trails B. None of the other cardiovascular disease risk were significant. For males, only diagnosis of hypertension significantly predicted Trails B scores (B = -2.41, 95% CI [-4.33 - -0.49], p = 0.01). For females, diagnosis of hypertension (B = -0.95, 95% CI [-1.93 – 0.03], p = 0.05), and dyslipidemia (B = -1.10, 95% CI [-2.17 - -0.03], p = 0.04) predicted Trails B scores.

Conclusion: Even though longitudinal research is needed to identify the long-term effect of blood pressure levels on cognition, our findings suggest a relationship between diagnosis of hypertension and executive function in both male and female Mexican Americans. This suggests control of blood pressure may be an essential factor in reducing cognitive decline.

Keywords: Cognition, Executive Function, Hypertension, Cardiovascular Risk Factors, Dyslipidemia, Alzheimer’s Disease, Vascular Dementia, Diabetes Mellitus, Pathologies, Neuropsychological

Two of the most common pathologies in western populations are cognitive impairment and hypertension. According to the United States Census Bureau, in 2050, the population aged 65 and older is projected to be 83.7 million, and it will also be more racially and ethnically diverse [1]. According to the Alzheimer’s Association, more that 5 million people over the age of 65 are living with dementia and the associated costs are estimated in $183 billion annually [2]. In 2016, the American Heart Association named age related dementia (Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia) as a major public health threat [3]. The most recent data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) estimated that more than 30% in the total US population had hypertension, and its prevalence increases with age to over 70% in those 80 years or older [4]. In the last decade a number of cross-sectional [5-7] and longitudinal studies [8-10] have investigated the relationship between blood pressure levels and cognitive impairment. Hypertension is a modifiable multifactorial risk factor [11] that damages the brain by causing changes in small and large cerebral blood vessels [12] and has been related to brain atrophy, white matter lesions, and neurofibrillary tangles [13].

Hypertension, has been linked to executive dysfunction, slowing of mental processing skills and less frequently memory impairment [3,12,14] described executive functions and frontal abilities as the main affected cognitive domains in hypertensives. In a population at risk of dementia, Goldstein et al. [15] found that hypertension associated with faster cognitive decline specifically in the areas of attention, executive functioning, and processing speed [15]. Although there is no consistency among studies about the specific cognitive systems that are affected [16-18] the decline of performance in different domains suggest that the neuropathological abnormalities are not located in isolated areas of the brain [19]. Along with hypertension a number of other cardiovascular risk factors such as dyslipidemia [20] abdominal circumference [21,22] and diabetes mellitus (DM) [23] have been studied as predictors of future memory and cognition decline. The research done to elucidate the relationship between CVRF and cognitive function produced diverse results. The heterogeneity of findings may be due to the dissimilarities among the population studied, and the lack of consistency of neuropsychological measures used.

The majority of these studies have investigated the relationship between cardiovascular risks and cognition in non-Hispanic white populations. Despite the fact that Mexican Americans have an increased risk to develop metabolic and vascular conditions [24] there has been limited research on cardiovascular risk, specifically high blood pressure, and cognition in this population [25-27]. Previous research has shown that Mexican Americans who develop cognitive decline have a higher prevalence of modifiable cardiovascular risks including hypertension compared to Non- Hispanic whites [28]. Given the availability of well-established methods for the treatment and prevention of high blood pressure, it is important to investigate the role of hypertension in cognitive functioning of Mexican Americans. The present study, investigated the relationship between blood pressure levels and executive function in cognitively normal Mexican-Americans from the Health and Aging Brain Study among Latino Elders.

Data from 349 participants (278 Females, 71 Males) enrolled in the Health and Aging Brain Among Latino Elders (HABLE) study who had been diagnosed as cognitively normal were analyzed. HABLE is an ongoing epidemiological study that examines factors affecting cognition in community–dwelling Hispanic elders in an urban setting [29]. The HABLE participants undergo an interview (i.e., medical history, medications, and health behaviors), clinical labs, medical examination, and neuropsychological testing. An informant interview was conducted for each participant to obtain information about activities of daily living. Diagnosis of hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia were based on medication status, medical history, examination results and self-report. Waist circumference was measured in inches at the umbilicus level with a cut out value of 40 inches for males and 35 inches for females [30]. Participants were interviewed and tested in either English or Spanish, based in his/her preference. Participants who performed within normal parameters on psychometric testing and had a Clinical Dementia Rating Global Score of O were classified as cognitively normal. The University of North Texas Health Science Center Institutional Review Board approval was attained for HABLE and written informed consent was obtained from all participants included in this study.

The neuropsychological battery includes tests of global cognition, attention, executive functioning, visuospatial ability and memory. Executive function was measured using the Trail Making Test part B. Executive function involves different processes such as attention, working memory, and impulse control to perform complex tasks [31]. Trail making tests (Part A and B) have been shown to assess these processes along with visual search and scanning, sequencing and shifting, and the ability to maintain two trains of thought simultaneously [32]. In Trails B, the participants draw lines to connect circled numbers and letters in an alternating numeric and alphabetic sequence (i.e., 1-A-2-B, etc.) as fast as possible. The scoring for Trails B is the time in seconds required for complete the test. The test is discontinued at 300 seconds if the participants is not able to complete in that period of time [32]. Trails B test scores were expressed by education-adjusted scaled scores. Data were analyzed using ANCOVA and logistic regression analysis. Age was entered into the model as covariate and gender differences were assessed. Analyses were conducted using SPSS version 22 software.

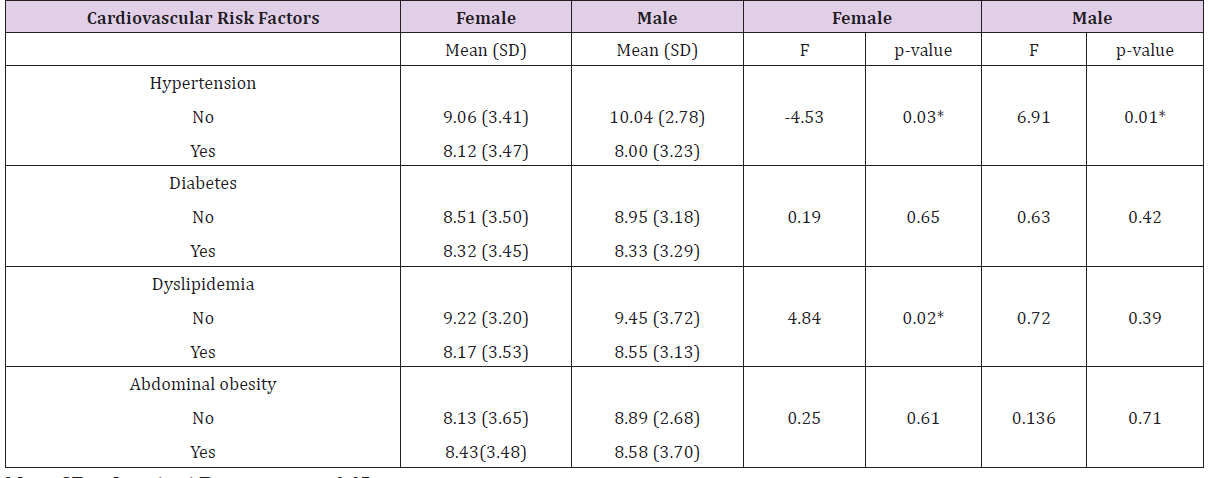

The characteristics of the HABLE sample are shown in Table 1. The sample was predominately female (80%), and vast majority of the sample (79%) were tested in Spanish. The mean age was 58.64 for women and 59.87 for men. Years of education were significantly higher for men (10.00 vs 8.78), no significant gender differences were found in the prevalence of hypertension or diabetes. Men had a significantly higher prevalence of dyslipidemia. Based on the percentage having abdominal circumference higher than the cut off level, women were significantly more likely to be overweight. The estimate means for the Trails B test are listed in Table 2. In general, Trail B means were higher in both, male and female participants, without a diagnosis of hypertension, diabetes and dyslipidemia. While the Trails B mean score for males without abdominal obesity were higher [8.89 (SD = 2.68)] than that the subjects with abdominal obesity, this was not true for female participants.

Note: SD = Standard Deviation, p < 0.05

Table 2: Trails B education-adjusted scale scores by cardiovascular risk factors ANOVA of executive measure (Trails B) by cardiovascular risk factor.

Note: SD = Standard Deviation, p < 0.05.

Male Note: Dependent variable: Trails B education-adjusted scale score.

F = 7.06 (model 1); F = 1.57 (model 2)

*P < = 0.05

Female Note: Dependent variable: Trails B education-adjusted scale score. F = 5.536 (model 1); F = 2.105 (model 2)

*P < = 0.05

Females with abdominal obesity had higher means in the Trails B test [8.43(SD = 3.48) versus 8.13 (SD = 3.65)]. The results of the study revealed statically significance difference between groups for male and female subjects with hypertension (F = 6.91, p = 0.03) and (F = 4.53, p = 0.03) respectively. The results in subjects with diabetes, dyslipidemia, and abdominal obesity were not significant. The multiple regression model with all four predictors produced R2 = 0.11, F (5, 61) = 1.57, p = 0.18 for males. As seen in Table 3, only diagnosis of hypertension significantly predicted Trails B scores (B = -2.41, 95% CI [-4.33 - -0.49], p = 0.01). For females, the regression model showed R2 = 0.04, F (5,25) = 2.10, p = 0.06. For this population, diagnosis of hypertension (B = -0.95, 95% CI [-1.93 – 0.03], p = 0.05), and dyslipidemia (B = -1.10, 95% CI [-2.17 - -0.03], p = 0.04) predicted Trails B scores.

Our study investigated the relationship between a diagnosis of hypertension and other cardiovascular risks and executive functioning in cognitively normal Mexican-Americans. In our study only a diagnosis of hypertension was significantly related to performance on a measure of executive functioning. This relationship was found for both women and men. Nine percent of the variance on Trails B scores for males, and two percent in females were explained by diagnosis of hypertension. The mechanisms by which cardiovascular risk factors affect cognitive functions are still controversial. Diabetes has been associated with insulin resistance, microvascular and macrovascular disease [33] dyslipidemia with increased production of B-amyloid, and high blood pressure and obesity with increased cerebral perfusion and cortical atrophy [26]. White matter injuries caused by cerebral vascular damage have been posited to explain the relationship between hypertension and cognitive decline [34,35]. The vast majority of research has been done in non-Hispanic-White subjects.

Although two studies did not report a linear relationship between hypertension and cognitive performance either in White subjects [36] or in Mexican-Americans [37] our study extends the growing number of studies that link cardiovascular risk factors and cognition in Latinos [26,38,39]. Consistent with prior research [13,40,41] our findings support the link between blood pressure levels and executive functions. Several limitations are clearly seen in the study. Our results were based on cross-sectional data so we were not able to identify the long term effect of high blood pressure levels on cognition. Also, the self-report diagnosis of hypertension and other cardiovascular risk factors opens the possibility of misclassification of subjects as having or not having the condition. Finally, even though we analyzed the effects of diabetes, dyslipidemia, and abdominal obesity, chances of residual cofounding exist because we do not have data on other variables like smoking and depression that may explain part of the effects of hypertension on executive function. In the current study we did not investigate the effect of treated hypertension and its relationship to executive functioning.

The strengths of the study include a community based design, and the inclusion only of cognitively normal individuals. Additionally, the use of Trails B education adjusted scaled scores provide a reliable and valid measure of executive function. Despite the limitations, we did find a significant relationship between diagnosis of hypertension and executive function occurring in cognitively normal Mexican Americans. The HABLE study is an ongoing longitudinal study, which will allow for future evaluation of the relationship between cardiovascular risk factors and cognition, specifically the risk factors’ response to treatment and the correlation to cognitive functions over time. Positive outcomes of that research may lay the ground work for the development of intervention programs to potentially reduce cognitive decline related to cardiovascular risks among the Mexican American population.

Research reported here was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AG054073. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The research team thanks the local Fort Worth community and participants of the Health & Aging Brain Study.