ABSTRACT

Elevated serum beta human chorionic gonadotropin (ß-hCG) in a female usually indicates pregnancy or less commonly, gestational trophoblastic disease or gonadal germ cell tumors. Elevation of hCG exists in other conditions including malignant tumors of non-endocrine origin. The elevated ß-hCG level can produce excessive amounts of estradiol via extra gonadal metabolism from androgen, and manifest as gynecomastia in males or vaginal spotting or suspicion of pregnancy in females. In either sex, ß-hCG might serve as a useful tumor marker during therapeutic management for checking recurrence of the disease.

Introduction

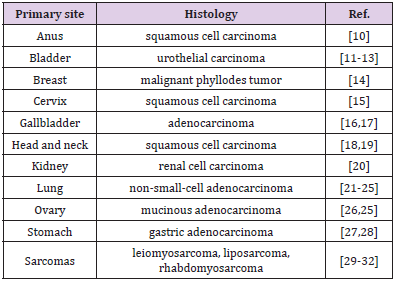

Elevated serum beta human chorionic gonadotropin (ß-hCG) in women generally indicates pregnancy, or less commonly, gestational trophoblastic disease, gonadal germ cell tumors, or extremely low levels from the anterior pituitary [1,2]. Elevation of hCG exist in several other states such as malignant tumors of nonendocrine origin (Figure1), and it has been suggested as possible tumor markers (Table 1). Some in vivo and in vitro studies have been shown that ß-hCG acts as an autocrine growth factor within tumor [3,4]. Elevated expression of ß-hCG may not be a reliable diagnostic marker, but it has been shown to serve as a strong indicator of poor prognosis for many non-endocrine tumors [1,3,4]. Elevated ß-hCG might manifest as gynecomastia in male patients or cause vaginal bleeding as initial symptoms in postmenopausal female patients [5-8]. These signs associated with high ß-hCG and subsequently increased level of estrogen may be attributed to paraneoplastic syndrome due to non-endocrine tumors. We purpose to understand the unusual sign of the ectopic ß-hCG producing malignancies as initial manifestation.

Gynecomastia in Males

Gynecomastia results from

1) Increased level of circulating estrogen, in particular estradiol,

2) Increased breast sensitivity to circulating estrogen, or

3) An altered balance of estrogen (stimulatory effect) and androgen (inhibitory effect).

Estrogen stimulates ductal epithelial hyperplasia, ductal branching and elongation, proliferation of the periductal stroma, and vascular distribution in the breast [5,6].

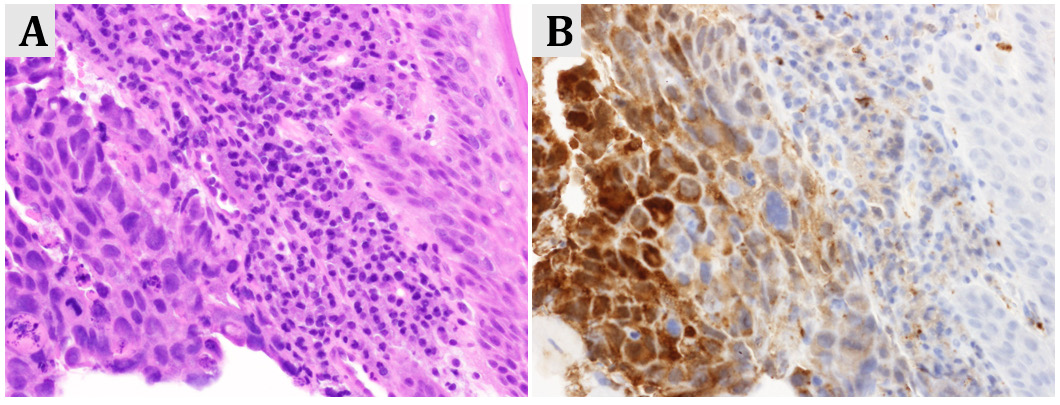

Figure 1: Stage IV gastric cancer in a postmenopausal women presenting with intermittent vaginal bleeding

(A) Microscopic image of gastric adenocarcinoma (hematoxylin/eosin staining, x400)

(B) Tumor cells were diffusely positive for human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG, x400).

Estrogen production in postmenopausal females and males results mainly from the peripheral conversion of androgens (testosterone, androstenedione and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate,) by the action of the enzyme aromatase to estradiol and estrone [7,8]. The extra gonadal formation of estrogen occurs mainly in adipose tissue, skin and muscle. The patients with malignant tumors characterized by ectopic production of ß-hCG (Table 1) may be associated with excessive amounts of estradiol via the extragonadal metabolism of androgens.

Vaginal Spotting in Females

The reproductive organs undergo progressive atrophy due to a reduced circulating estrogen and progesterone. This physiologic process of aging is also found at an endometrial level. Without the cyclic hormonal actions of the menstrual cycle, the endometrium during menopause becomes atrophic [9-18]. Non-physiologically increased estrogen level may cause postmenopausal bleeding. In a patient with unexplained vaginal spotting and no evidence of endometrial cancer or endometrial or cervical polyps, consideration should be given to the possibility of ectopic secretion of ß-hCG from other tumors.

Suspicion of Pregnancy in Premenopausal Females

In reproductive-aged women with elevated hCG, when pregnancy, either normal of abnormal (e.g. missed abortion, ectopic pregnancy)) is excluded, the malignancy should [18-24] be ruled out with imaging and surgical specimen immunohistochemically.

Comments

Pituitary hCG is naturally produced at extremely low levels in woman of reproductive age population. In peri- or postmenopausal state, levels of pituitary hCG increase because of the absence of feedback control by circulating estrogen and progesterone [2,25- 32]. Elevated ß-hCG level due to various cancers produce excessive amounts of estradiol by peripheral aromatase activation, which can manifest as gynecomastia in males or vaginal spotting in females. In either case estrogen and ß-hCG might be useful tumor markers during therapeutic management for checking recurrence of the disease, alongside other examination.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Cole LA (2009) New discoveries on the biology and detection of human chorionic gonadotropin. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 7: 8.

- Cole LA, Sasaki Y, Muller CY (2007) Normal production of human chorionic gonadotropin in menopause. N Engl J Med 356: 1184-1186.

- Iles RK (2007) Ectopic hCG beta expression by epithelial cancer: malignant behaviour, metastasis and inhibition of tumor cell apoptosis. Mol Cell Endocrinol 260-262: 264-270.

- Stenman UH, Alfthan H, Hotakainen K (2004) Human chorionic gonadotropin in cancer. Clin Biochem 37: 549-561.

- Glass AR (1994) Gynecomastia. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 23: 825-837.

- Bindra A, Braunstein GD (1993) Gynecomastia. N Engl J Med 328: 490-549.

- Kirschner MA, Lippman A, Berkowitz R, Mayrer E, Drejka M (1981) Estrogen production as a tumor marker in patients with gonadotropin-producing neoplasms. Cancer Res 41: 1447-1450.

- Nelson LR, Bulun SE (2001) Estrogen production and action. J Am Acad Dermatol 45: S116-124.

- Carugno J (2020) Clinical management of vaginal bleeding in postmenopausal women. Climacteric 23: 343-349.

- Pokharel K, Gilbar PJ, Mansfield SK, Nair LM, So A (2020) Elevated beta human chorionic gonadotropin in a non-pregnant female diagnosed with anal squamous cell carcinoma. J Oncol Pharm Pract 26(5): 1266-1269.

- Benyo AK, Herring D, Greenwood H, Maloney DJL (2010) The expression of beta human chorionic gonadotrophin (β-HCG) in human urothelial carcinoma. Pan Afr Med J 7: 20.

- Kawamura J, Machida S, Yoshida O, Oseko F, Imura H, et al. (1978) Bladder carcinoma associated with ectopic production of gonadotropin. Cancer 42: 2773-2780.

- Reisenbichler ES, Krontiras H, Hameed O (2009) Beta-human chorionic gonadotropin production associated with phyllodes tumor of the breast: An unusual paraneoplastic phenomenon. Breast J 15: 527-530.

- Mustafa A, Bozdag Z, Tepe NB, Ozcan HC (2016) An unexpected reason for elevated human chorionic gonadotropin in a young woman. Cervical squamous carcinoma. Saudi Med J 37(8): 905-907.

- Leostic A, Tran PL, Fagot H, Boukerrou M (2017) Elevated human chorionic gonadotrophin without pregnancy: A case of gallbladder carcinoma. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod 47(3): 141-143.

- Sato S, Ishii M, Fujihira T, Ito E, Ohtani Y (2010) Gallbladder adenocarcinoma with human chorionic gonadotropin: A case report and review of literature. Diagn Pathol 5: 46.

- Turner JH, Ross H, Richmon J (2010) Secretion of beta-HCG from squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 143(1): 169-170.

- Ferlito A, Elsheikh MN, Manni JJ, Rinaldo A (2007) Paraneoplastic syndromes in patients with primary head and neck cancer. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 264(3): 211-222.

- Adekunle AN, Lam AS, Turbow SD, Stallworth CR, Ferris MJ, et al. (2016) Beta-human chorionic gonadotropin-producing renal cell carcinoma. Am J Med 129: e29-31.

- Goyal A, Singh N, Bal A, Behera D (2013) Gynaecomastia, galactorrhoea, and lung cancer in a man. Lancet 381: 1332.

- Wong YP, Tan GC, Aziz S, Pongprakyun S, Ismail F (2015) Beta-human chorionic gonadotropin-secreting lung adenocarcinoma. Malays J Med Sci 22(4): 76-80.

- Groza D, Duerr D, Schmid M, Boesch B (2017) When cancer patients suddenly have a positive pregnancy test. BMJ Case Rep 2017: bcr2017220493.

- Lazopoulos A, Krimiotis D, Schizas NC, Rallis T, Gogakos AS, et al. (2018) Galactorrhea, mastodynia and gynecomastia as the first manifestation of lung adenocarcinoma; a case report. Respir Med Case Rep 26: 146-149.

- Okutur K, Hasbal B, Aydin K, Bozkurt M, Namal E, et al. (2010) Pleomorphic carcinoma of the lung with high serum beta-human chorionic gonadotropin level and gynecomastia. J Korean Med Sci 25(12): 1805-1808.

- Goldstein J, Pandey P, Fleming N, Westin S, Piha-Paul S (2016) A non-pregnant woman with elevated beta-HCG: A case of para-neoplastic syndrome in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol Rep 17: 49-52.

- Wagner V, Winn H, Newtson A, Bender D, McDonald M (2018) hCG production by mucinous adenocarcinoma of the ovary in a reproductive aged woman. Gynecol Oncol Rep 26: 102-104.

- Ben Kridis W, Ben Hassena R, Charfi S, Toumi N, Boudawara T, et al. (2018) Gastric signet-ring cell carcinoma with hypersecretion of β-Human chorionic gonadotropin and review of the literature. Exp Oncol 240(2): 149-151.

- Eivaz-Mohammadi S, Gonzalez-Ibarra F, Abdul W, Tarar O, Malik K, et al. (2014) Her2+ and b-HCG producing undifferentiated gastric adenocarcinoma. Case Rep Med 2014: 268919.

- Meredith RF, Wagman LD, Piper JA, Mills AS, Neifeid JP (1986) Beta-chain human chorionic gonadotropin-producing leiomyosarcoma of the small intestine. Cancer 58(1): 131-135.

- Froehner M, Gaertner HJ, Manseck A, Oehlschlaeger S, Wirth M (2000) Retroperitoneal leiomyosarcoma associated with an elevated beta-hCG serum level mimicking extragonadal germ cell tumor. Sarcoma 4(4): 179-181.

- Demirtas E, Krishnamurthy S, Tulandi T (2007) Elevated serum beta-human chorionic gonadotropin in nonpregnant conditions. Obstet Gynecol Surv 62(10): 675-679.

- Maryamchik E, Lyapichev KA, Halliday B, Rosenberg AE (2018) Dedifferentiated liposarcoma with rhabdomyosarcomata’s differentiation producing HCG: A case report of a diagnostic pitfall. Int J Surg Pathol. 26: 448-452.

Mini Review

Mini Review