ABSTRACT

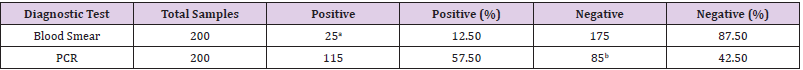

Theileria annulata causes bovine tropical theileriosis, a tick-borne disease with major economic implications in tropical and subtropical areas of the world. The purpose of this study was to use polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to detect theilerosis in Kundhi Buffaloes. Theileriosis is often diagnosed using a blood smear staining technique that is insufficiently sensitive to detect piroplasms in carrier animals. A total of n = 200 samples were taken from sick and apparently healthy Kundhi Buffaloes for this study. Giemsa staining of blood smears revealed 25 samples (12.5%) positive for Theileria piroplasms out of a total of 200 samples. However, PCR-based screening utilizing specific primers from the T. annulata (Tams1) gene’s main merozoitepiroplasm surface antigen sequence discovered 115 samples (57.50%) positive for T. annulata. According to our findings, PCR-based screening is a more sensitive and accurate method for diagnosing tropical theileriosis in Kundhi buffaloes.

Keywords: Theileria Annulata; PCR, Sensitive; Kundhi Buffaloes; Hyderabad; Sindh

Abbreviations: PCR: Polymerase Chain Reaction; ELISA: Immunosorbent Assays; IFAT: Immunofluorescent Antibody Test; IHA: Indirect Haemagglutination Assay

Introduction

Ticks are a big problem for buffaloes in tropical nations like Pakistan because they create health problems and act as a vector for the spread of haemoprotozoan diseases such theileriosis, babesiosis, and anaplasmosis. Exotic (Bos taurus) and crossbred cattle and buffaloes are known to be extremely susceptible, but indigenous cattle have built-in disease resistance [1]. In Pakistan, cross-breeding programmes were implemented to improve the genetics of livestock, but the downside was a reduction in resistance to ticks and tick-borne diseases [2]. [3] Estimated a global loss of US $ 800 million per year owing to tropical theileriosis. In Pakistan, the annual cost of T. annulata infection is estimated to be 384.3 million US dollars [4]. Theileriosis causes significant economic loss due to decreased productivity and mortality [5]. Theileria are small parasitic parasites with round, ovoid, irregular, or bacilliform shapes that belong to the Phylum Apicomplexa, Subclass Piroplasmorina, Order Piroplasmorina, and Family Theileriidae. Clinically, theileriosis has been linked to symptoms that range from mild to deadly [6]. Clinical symptoms and microscopic inspection of stained thin blood smears are used to diagnose theileriosis in acute cases [7]. However, both native and treated animals turn out to be long-term carriers, with just a small percentage of contaminated erythrocytes [8], making parasite detection in blood smear challenging [9].

Long-term carriers are the primary source of infection transmitted by ticks [10]. Disease outbreaks can occur when carrier livestock are transported to non-endemic areas [11]. As a result, detecting piroplasms in carrier animals becomes more difficult. The lack of a strong physical distinction between the several Theileria species in schizonts and piroplasms hampers species classification on blood slides [12]. Furthermore, the smear approach is linked to false negative results and has little sensitivity when it comes to detecting carrier livestock [13]. The introduction of molecular diagnostic procedures such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) has paved the door for more effective diagnosis than previous methods [14]. Based on research conducted on a variety of parasites, it has been determined that PCR is more sensitive than traditional approaches [15]. For the identification of Theileria species, [16] developed PCR, reverse line blot assay, and DNA probes. T. annulata was detected using four diagnostic tests: blood and lymphnode biopsy smear examination, PCR of blood and lymphnode biopsy sample, and PCR of blood and lymphnode biopsy sample. The PCR assay was shown to be more sensitive and accurate than microscopic examination among them [17]. Theileriosis can be diagnosed more accurately with the use of PCR [18]. The goal of the study was to use PCR to assess the existence of theileriosis in Kundhi Buffaloes and to reliably diagnose the disease.

Materials and Methods

Collection of Blood Samples

A total of n = 200 blood samples from Kundhi Buffaloes were collected from animals with clinical signs of theileriosis, such as anorexia, pyrexia, decreased milk production, tick infestation, lymphnode enlargement, pale mucous membrane, suspended rumination, bilateral nasal discharge, lacrimation, and others, as well as from animals that appeared to be healthy. The blood smears were made using blood taken from the jugular vein according to [18]. 3ml of blood were taken in EDTA-coated vacutainers for the PCR.

Giemsa Staining

Giemsa stain was used to prepare thin blood smears and stain them. The parasites were identified using [19] characters as a guide.

Isolation Of DNA from Blood Samples

A DNA extraction kit (HiPura, Himedia) was used to extract genomic DNA from 200 μl of whole blood according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted DNA was spectrophotometrically measured before being run on a 0.8 % agarose gel. Extracted DNA aliquots were kept at -20 0C until needed.

Polymerase Chain Reaction

The primers were created using the coding sequence of T. annulata’s primary merozoite surface antigen (Tams 1 gene). 50 -CCAG GACCACCCTCAAGTTC-30 and 50 -GCATCTAGTTCCTTGGCGGA-30 are the forward and reverse primer sequences, respectively. In a total volume of 15 μl the PCR reaction contained 30 ng of template DNA, 7.5 μl of Fermentas 29 Master mix, 0.5 μl of each forward and reverse primer (10 pmol/ μl), and 5.5 μl of nuclease-free water. In a thermal cycler, reactions were started at 95°C for 5 minutes, followed by 37 cycles of 95°C for 30 seconds, 55°C for 30 seconds, 72°C for 30 seconds, and a final elongation step at 72°C for 5 minutes, with a final hold at 4°C (Veriti). Each amplification run comprised a negative control (sterile water) and a positive control DNA from a T. annulata.

Agarose gel Electrophoresis

Electrophoresis (120 V/208 mA) in a 1.5 % agarose gel was used to examine amplified samples. Along with each round of amplifications, positive and negative controls were run. A UV transilluminator was used to observe the gel, which was stained with ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/ml) (Gel Doc, Syngene).

Statistics Analysis

The connection between blood smear examination and PCR was investigated using the Chi square test.

Results

Blood Smear Examination

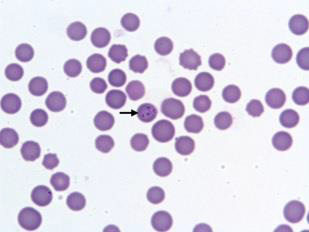

The stained blood films revealed the presence of Theileria piroplasms, forms with diameter of 0.5–1.5 micrometer in 25 samples (12.50 %) of Kundhi buffaloes (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Piroplasmic forms of T. annulata in a microscopic field by Giemsa staining method Polymerase Chain reaction.

Polymerase Chain Reaction

PCR-based screening utilizing specific primers from the Theileria annulata (Tams1) gene’s main merozoite-piroplasm surface antigen sequence revealed 115 samples (57.50%) positive for T. annulata were found to be positive by PCR.

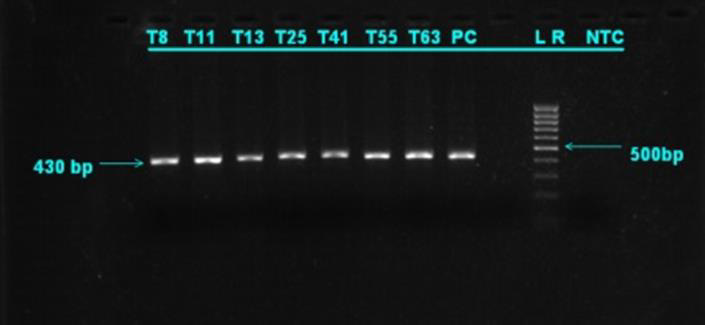

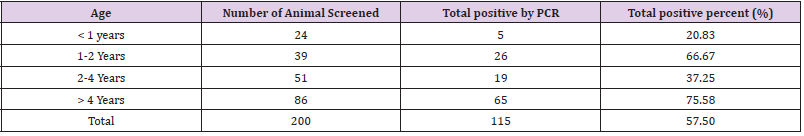

The prevalence of disease in Kundhi buffaloes by age when screened by PCR. The highest incidence was found in buffaloes over the age of 5 years (75.58%), while the lowest prevalence was found in calves under the age of 1 year (20.83%) (Table 1). In T. annulata positive samples, the desired product size of 430 bp was reached (Figure 2). (Table 2) shows the 2x2 contingency table for blood smear examination and PCR. (Figure 2) PCR products run on 1.5 % agarose gel positive samples showing amplified product of 430 bp. Lane 1 Sample 8 (positive), lane 2 sample 11 (positive), lane 3 sample 13 (positive), Lane 4 sample 25 (positive), lane 5 sample 41 (positive), lane 6 sample 55 (positive), Lane 7 sample 63 (positive), lane 8 positive control, lane 10 DNA ladder (mass ruler low range), Lane 11 negative control.

Figure 2: PCR products run on 1.5 % agarose gel positive samples showing amplified product of 430 bp.

Table 2: 2 x 2 Contingency table for blood smear and PCR.

Note: aTrue Positive

bTrue Negative

Sensitivity of PCR = 100%

Specificity of PCR = 42.58%

Statistics Analysis

Chi Square was found to have a value of 8.76. Because this value is more than 3.841, the Chi square value is significant at the 5% threshold of significance, and so it provides adequate grounds to assume that PCR is more effective in diagnosing theileriosis than microscopic testing.

Discussion

Tropical theileriosis frequently results in a severe and deadly infection. Anorexia, emaciation, decreased rumination, lacrimation, corneal opacity, nasal discharge, diarrhea, terminal dyspnea, and frothy nasal discharge are all symptoms of theileriosis infection in Kundhi buffaloes [20]. Because it is simple and inexpensive, clinical indicators and microscopic inspection are commonly used to diagnose piroplasmic infection. However, a lack of sensitivity and precision in the staining process could result in a mistaken diagnosis. Although serological tests are used to diagnose latent infection, there is a potential that false positive and negative results will occur [21]. In comparison to Immunosorbent Assays (ELISA), Immunofluorescent Antibody Test (IFAT), and Indirect Haemagglutination Assay (IHA), as well as morphological identification of piroplasmic forms, the PCR approach is more accurate [22]. In a study conducted by [23], the prevalence of Theileria infection by PCR assay was found to be 70% (21 out of 30), while the prevalence by Giemsa staining method was 30% (9 out of 30). [24] also reported that the number of positive cases of theileriosis by PCR and smear method were 22 (44%) and 8 (16%), respectively, out of 50 blood samples of native buffaloes. According to [25], PCR revealed that 68 of 150 carrier cattle (45.33 %) were positive. Our findings show that PCR is more effective than conventional staining in detecting theileriosis, which is consistent with earlier research [26,27] and [28]. [29] created a multiplex PCR assay for simultaneous detection of T. annulata, Babesia bovis, and Anaplasma marginale, which they found to be a useful diagnostic tool.

The Tams1 gene, which encodes the 30 kDa main T. annulata merozoite surface antigen, was amplified with the primers employed in this investigation [30]. [31] employed the 30 kDa merozoite surface protein gene as a detective target sequence, developing specialized primers to amplify just T. annulata, which is similar to our target. T. annulata was detected utilizing Tams1 genespecific primers, and the PCR technique was shown to be sensitive and specific [32]. [33] investigated the efficacy of two primer sets, primer set one (N516/N517) and primer set two (Tams1F/ Tspm1R), in amplifying the 30 kDa major merozoite surface antigen gene for the diagnosis of T. annulata infection in buffaloes and concluded that primer set Tams1F/Tspm1R is the primer set of choice for T. annulata diagnosis. This explains why we used Tams1- specific primers in our investigation, as well as demonstrating the efficiency of the PCR approach for theileriosis confirmation. [34] found a higher incidence of T. annulata in buffaloes aged 4–6 years, which is consistent with the current study, which found the highest prevalence in calves aged above 5 years. Physiological variables such as oestrus, pregnancy, and lactation cause transient immune reduction, which leads to an increase in disease occurrence in adult animals, as stated by [35].

Antibodies to sporozoites, schizonts, and piroplasms have been found in immune cows’ colostrum and calves’ serum, which protects the calves from theileriosis. This could explain the low prevalence of theileriosis in calves younger than a year in our study [36]. The present investigation found that young animals were more resistant to T. annulata than adults, which was consistent with [37-39] findings that young cows were more resistant than older buffaloes. [32] Demonstrated age-related resistance in young cattle to most tick-borne protozoan and [31]. The Giemsa-stained blood smears in our investigation showed false negative in visual examination under a light microscope, indicating that this test has a limited sensitivity. It could be due to a variety of factors, including visual errors made during slide examination, very low parasitaemia, hemolysis-induced destruction of piroplasmic forms in red blood cells, thickness, dirtiness, or inadequate blood smear staining [15]. Furthermore, piroplasms could not be detected microscopically in samples that were negative on PCR tests. This fact demonstrates that PCR is superior to blood smear examination. At the 5% level, a statistical comparison of blood smear and PCR revealed a significant difference.

The sensitivity of the PCR method was shown to be 100 % when using blood smear examination as the gold standard assay. The results of this study accord with those of [2], who found that PCR had higher sensitivity and accuracy than blood smear examination in detecting T. annulata. In epidemiological studies, [29] confirmed the efficacy of this technology and compared it to conventional diagnostic procedures, finding that PCR was more sensitive for identification of T. annulata infections. Drug therapy lowers parasitaemia levels, making correct diagnosis difficult [10]. PCR assays can be used to detect low parasitaemias in the blood of carrier animals under these situations. In the diagnosis of field difficulties of theileriosis, [31] revealed that the PCR test had the highest overall comparative efficacy of 31.6 %, followed by microscopic lymph node smear examination 8.25 %, and microscopic blood smear examination 6 %. Thus, compared to microscopic blood and lymph node smear testing, the PCR test is more sensitive in detecting low-grade illnesses in carrier animals, making it more suitable for epidemiological surveys. [1] reported a similar observation, claiming that tick carriers are substantial contributors to the infection. Molecular technologies such as PCR overcome the challenges of conventional approaches in detecting and distinguishing Theileria piroplasms. According to [3], the great effectiveness and sensitivity of PCR makes it an appealing method for diagnosing tick-borne illnesses [9]. As a result, our research clearly demonstrates that PCR may be used to accurately diagnose theileriosis, as well as to discover carrier animals, which can serve as a possible source of infection to healthy populations via infected ticks.

References

- Ahmed JS, Mehlhorn H (1999) Review: the cellular basis of the immunity to and immunopathogenesis of tropical theileriosis. Parasitol Res 85(7): 539-549.

- Aktas M, Altay K, Dumanli N (2006) A molecular survey of bovine theileria parasites among apparently healthy cattle and with a note on the distribution of ticks in eastern Turkey. Vet Parasitol 138: 179-185.

- Ananda KJ, D’Souza PE, Puttalashmamma GC (2009) Prevalence of haemoprotozoan diseases in crossbred cattle in Bangalore North. Vet World 2(1): 15-16.

- Campbell JDM, Spooner RI (1999) Macrophages behaving badly: infected cells and subversion of immune responses to Theileria annulata. Parasitol Today 15(1): 10-15.

- Collins NE, Allsopp MT, Allsopp BA (2002) Molecular diagnosis of theileriosis and heartwater in bovines in Africa. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 96(Suppl 1): S217-S224.

- Darghouth MEA, Bouattour A, Ben Miled L, Sassi L (1996) Diagnosis of Theileria annulata infection of cattle in tunisia: comparison of serology and blood smears. Vet Res 27(6): 613-627.

- Bishop R, Sohanpal B, Kariuki DP, Young AS, Nene V, et al. (1992) Detection of a carrier state in Theileria parva-infected cattle by the polymerase chain reaction. Parasitol 104: 215-232.

- Bilgic BH, Karagenc T, Simuunza M, Shiels B, Tait A, et al. (2013) Development of multiplex PCR assay for simultaneous detection of Theileria annulata, Babesia bovis and Anaplasma marginale in cattle. Exp Parasitol 133(2): 222-229.

- Dehkordi FS, Parsaei P, Saberian S, Moshkelani S, Hajshafiei P, et al. (2012) Prevalence study of Theileria annulata by comparison of four diagnostic techniques in southwest Iran. Bulg J Vet Med 15(15): 123-130.

- Durrani AZ (2003) Epidemiology, serodiagnosis and chemoprophylaxis of theileriosis in cattle. University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, Lahore.

- Fukasawa M, Kikuchi T, Konashi S, Nishida N, Yamagishi T (2003) Assessment of criteria for improvement in Theileria orientalis sergenti infection tolerance. Anim Sci J 74(1): 67-72.

- Gubbles MJ, Hong Y, Weide MVD, Qi B, Nijman IJ, et al. (2000) Molecular characterization of the Theileria buffeli/orientalis group. Int J Parasitol 30(8): 943-952.

- Habibi GR, Esmaeil NK, Bozorgi S, Najjar E, Hashemi FR, et al. (2007) PCR-based detection of Theileria infection and molecular characterization of Tams 1 T. annulata vaccine strain. Arch Razi Inst 62(2): 83-89.

- Bailey WS (1955) Veterinary parasite problems. Public Health Rep 70(10): 976-982.

- Brown CGD (1997) Dynamics and impact of tick-borne diseases of cattle. Trop Anim Health Prod 29: 15-35.

- Dumanli N, Aktas M, Cetinkaya B, Cakmak A, Koroglu E, et al. (2005) Prevalence and distribution of tropical theileriosis in eastern Turkey. Vet parasitol 127(1): 9-15.

- El Hussein AM, Mohamed SA, Osman AK, Osman OM (1991) A preliminary survey of blood parasites and brucellosis in dairy cattle in northern state. Sudan J Vet Res 10: 51-56.

- Hoghooghi Rad N, Ghaemi P, Shayan P, Eckert B, Sadr-Shirazi N (2011) Detection of native carrier cattle infected with Theileria annulata by semi-nested PCR and smear method in Golestan Province of Iran. World Appl Sci J 12(3): 317-323.

- Mahmmod YS, El-Balkemy FA, Yuan ZG, El-Mekkawy MF, Monazie AM, et al. (2010) Field evaluation of PCR assays for the diagnosis of tropical theileriosis in cattle and water buffaloes in Egypt. J Ani Vet Adv 9(4): 696-699.

- Kirvar E, Ilhan T, Katzer F, Hooshmand-rad P, Zweygarth E, et al. (2000) Detection of in cattle and vector ticks by PCR. Parasitol 120(3): 245-254.

- Zaeemi M, Haddadzadeh H, Khazraiinia P, Kazemi B, Bandehpour M (2011) Identification of different Theileria species (T. lestoquardi, T. ovis, and T. annulata) in naturally infected sheep using nested PCR-RFLP. Parasitol Res 108(4): 837-843.

- Sanchez MJ, Viseras J, Adroher FJ, Garcia Fernandez P (1999) Nested polymerase chain reaction for detection of Theileria annulata and comparison with conventional diagnostic techniques: its use in epidemiology studies. Parasitol Res 85(3): 243-245.

- Razmi GR, Hossini M, Aslani MR (2003) Identification of tick vectors of ovine theileriosis in an endemic region of Iran. Vet Parasitol 116(1): 1-6.

- Mahmoud R, Ellah Abd, Amira AT, Hosary AL (2011) Comparison of primer sets for amplification of 30 kDa merozoite surface antigen of bovine theileriasis. J Ani Vet Adv 10(12): 1607-1609.

- Minjauw B, McLeod A (2003) Tick-borne diseases and poverty. The impact of ticks and tick-borne diseases on the livelihood and marginal livestock owners in India and Eastern and Southern Africa Research report, DFID Animal Health Programme, Centre of Tropical Veterinary Medicine, University of Edinburgh.

- Glass EJ (2001) The balance between protective immunity and pathogenesis in tropical theileriosis: what we need to know to design effective vaccines for the future. Res Vet Sci 70(1): 71-75.

- Morzaria SP, Musoke AJ, Latif AA (1988) Recognition of theileria parva antigens by field sera from Rusinga, Kenya (Abstract). The Kenya Vet 12(2): 88-90.

- Morzaria SP, Musoke AJ, Latif AA (1988) Recognition of theileria parva antigens by field sera from Rusinga, Kenya (Abstract). The Kenya Vet 12(2): 88-90.

- Azizi H, Shiran B, Farzaneh Dehkordi A, Salehi F, Taghadosi C (2008) Detection of Theileria annulata by PCR and its comparison with smear comparison with smear method in native carrier cows. Vet Parasitol 99: 249-259.

- Bekker CP, De Vos S, Taoufik A, Sparagano OA (2002) Anaplasma and Ehrlichia species in ruminants and detection of Ehrlichia ruminantium in Amblyomma variegatum ticks by reverse line blot hybridization. Vet Microbiol 89: 223-238.

- Christine O (1995) Detection of Theileria annulata in blood samples of carrier cattle by PCR test. J Clin Microbiol 77: 266-269.

- Dolan TT, Teale AJ, Stagg DA, Kemp SJ, Cowan KM, et al. (1984) A histocompatibility barrier to immunization against east coast fever using Theileria parva-infected lymphoblastoid cell lines. Parasite Immunol 6(3): 243-250.

- Roy KC, Ray D, Bansal GC, Singh RK (2000) Detection of Theileria annulata carrier cattle by PCR. Indian J Exp Biol 38(3): 283-284.

- Saeid R, Fard N, Khalili M, Ghalekhani N (2013) Detection of Theileria annulata in blood samples of native cattle by PCR and smear method in southeast of Iran. JOPD 39(2): 249-52.

- Soulsby EJL (1982) Helminths, arthropods and protozoa of domesticated animals (7th)., Baillier Tindall and Cassel Ltd, London.

- Uilenberg G, Perie NM, Lawrence JA, de Vos AJ, Paling RW, et al. (1982) Causal agents of bovine theileriosis in southern Africa. Trop Anim Health Prod 14(3): 127-140.

- Utech KB, Wharton RH (1982) Breeding for resistance to Boophilus microplus in Australian illawarra shorthorn and Brahman x Australian illawarra shorthorn cattle. AVJ 58(2): 41-46.

- Olivier AE, Gubbels MJ, Guido R, Alexender P, Jongejan F (1999) Proceedings of the integrated molecular diagnosis of Theileria and Babesia Species of cattle in Italy. Stvm 5th Biennial Conf. Society for Tropical Veterinary Medicine.

- Tahar R, Ringwald P, Basco LK (1997) Diagnosis of Plasmodium malariae infection by the polymerase chain reaction. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 91(4): 410-411.

Research Article

Research Article