Abstract

Antibodies and antibody fragments have found wide application for therapeutic and diagnosis purposes. Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), as a prevalent tool for cancer diagnostics, still hold significant shortcomings, because they possess limited tumor penetration and high manufacturing costs. However, recent years, single-domain antibody fragments, known as “nanobodies”, the smallest functional antibody fragment, are a recent addition to the toolbox and have arisen as an alternative to conventional antibodies (Abs) and show great potential when used as tools in different biotechnology fields such as diagnostics and therapy. This review summarizes the latest advances of Nanobodies’ potential use for non-invasive in vivo imaging and for in vitro assays. Moreover, concerning non-invasive imaging applications, we highlight some already reported examples about nanobodies being used for the imaging of several cancers. Finally, future trends, opportunities, and disadvantages are also discussed.

Keywords: Nanobody; Non-invasive Imaging; Cancer; Cancer Biomarkers

Abbreviations: Abs: Antibodies; CT: Computed Tomography; SPECT: Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography; PET: Positron Emission Tomography; ECM: Extracellular Matrix

Introduction

Imaging is a useful and essential tool for making the correct

clinical decisions for many diseases, including cancer. Many different

imaging modalities have been developed ranging from conventional

microscopy methods, aimed at single cells and multiphoton intravital

microscopy, to non-invasive methods at the organismal level,

such as single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT),

positron emission tomography (PET), magnetic resonance imaging,

computed tomography (CT), bioluminescence and ultrasound

imaging. The ability to image biological processes of a living animal

and to diagnose signs of disease, have always been desirable goals.

With the ongoing development of targeted therapies, it has become

more and more important to visualize the presence tumor antigens

and immune infiltrates to predict responsiveness [1].

There are several factors to be necessarily considered for

designing a specific imaging agent. Once a tracer is injected into the

blood stream, it must penetrate the tissue and then bind to its target.

A tracer may accumulate in a tissue without binding specifically

to its target. Furthermore, immunohistochemistry is needed to

perform to confirm specificity and characterize the sensitivity of a

tracer. Molecular imaging with labeled antibodies, extensively with

labeled monoclonal Abs (mAbs), has been intensely explored, due

to their particular characteristics such as high affinity and high specificity, and considered one of the best biomolecules applied for

detection and targeting purposes. This can be useful for research,

diagnostics, and therapeutic applications [2]. The application

of antibodies in molecular imaging can help to overcome the

challenge of specificity. Antibodies exist for many cell-surfaceavailable

markers. Antibodies can detect cancer-specific markers

and identify components of the tumor Extracellular Matrix (ECM)

or tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Using radiolabeled antibodies

and antibody fragments as imaging agents can be able to visualize

and track location, movement and quantity of the target molecule,

thereby showing insight into its dynamics.

However, antibodies’ difficult tissue penetration and longer

serum half-life are strong obstacles in creating high-contrast

images and cancer detection. The optimal non-invasive imaging

agent would be able to penetrate tissues to allow rapid imaging

after injection and show high specificity and sensitivity. The

patient’s radiation exposure time should be minimized. Single

domain Abs or commonly named nanobodies (Nbs), produced

mainly in camelids such as llamas, alpacas, or camels, are only 15-

kDa small size and improve the penetrability when compared with

the performance of conventional mAbs (150 kDa) [3]. Moreover,

Nbs own the characteristic of rapid renal clearance, avoiding

toxicity effects [4]. One of the main advantages of obtaining Nbs

by recombinant technology is that several tags can be fused in

their tertiary structure such as His-tag or even fluorescent labels

like the green fluorescent protein (GFP) [5]. Considering these

characteristics, Nbs are particularly suited for targeting tumors and

non-invasive imaging. Thus, Nbs form quite suitable candidates,

ensuring minimal non-target retention to create a high tumor-tobackground

ratio (T/B) shortly after administration.

Nanobody

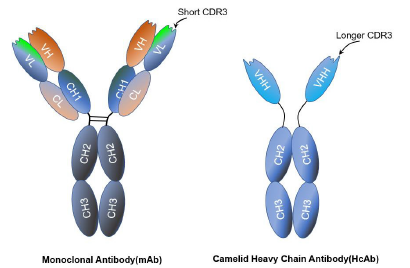

Nbs, the single domain antigen-binding fragments obtained mainly from the Camellidae such as llamas, alpacas, or camels. Normally, IgGs are formed from four polypeptidechains comprising two light chains (L) and two heavy chains (H). These host animals have the ability to produce immunoglobulins which only contain the heavy chain (HcAb) and completely lack the light chain. The heavy chain is structured into two constant regions (CH2 and CH3), a long hinge region, and the Ag-binding domain VHH [6]. Specifically, VHH is formed from different regions, ones that are more conserved (FR) and others that are responsible for the specific recognition of the Ag, called complementary determining regions (CDRs) [7]. Nbs present three CDRs instead of six occurring in conventional Abs [8,9]. The one called CDR3, usually longer than the VH domains of mAbs, being the region that shows best degree of recognition [4] (Figure1). Nbs have numerous attractive advantages over conventional monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) [5-7] include small size (15 kDa), high stability, high solubility and specificity, ease of genetic design and excellent tissue penetration in vivo.

The folding of CDR3 loop and the hydrophilic content of the framework-2 region keeps Nbs high solubility in aqueous solutions and lack of aggregation [10]. High thermal stability keeps Nbs full binding capacities for 1 week at 37℃ [11], and even completely reversible after long incubation periods at 90°C [12]. High tolerance against extreme pHs makes Nanobody great stability between pH 7.4 and [10,13] as well as in the presence of proteases [14]. The optimal biophysical and biochemical properties allow Nbs to be used for diagnostic purposes.

Recognition of Hidden Epitopes

Crystallographic studies of Nbs have revealed that in most cases the Ag-binding surface is clefts and cavities [15]. The lack of variable light chain (VL) is balanced with a VHH region that shows an extended CDR1 and a more exposed CDR3. These structural changes allow Nbs to bind planar surfaces and cavities, and also possibly bind the protruding loops or clefts [16]. Therefore, this feature of Nbs and their smaller size explain the ability of Nanobody to bind and neutralize targets that are notoriously difficult to hit with conventional Abs.

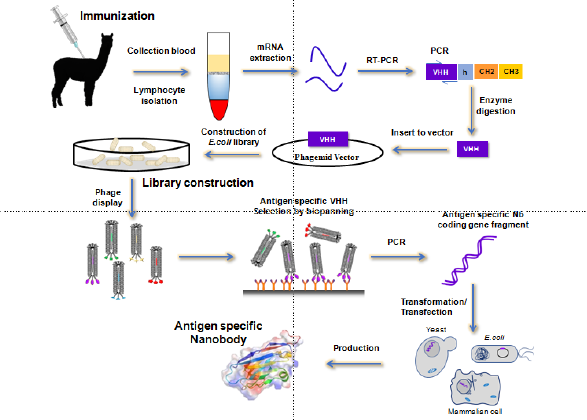

The Development and Production of Nbs

Obtaining libraries that contain the required genetic information is critical to produce Nbs with high specificity and affinity properties. At present, there are mainly three technologies for Agspecific Nbs’ preparation including immune, naïve, or synthetic libraries [9]. Immune libraries are the most common option for the development of Nbs, which requires an active immunization of Camelidae animals. Once the specific sequence is amplified from the extraction of mRNA from isolated lymphocytes and inserted in a cloning vector, the screening process is performed to isolate the most suitable Nbs by taking advantage of phage display technology, or using other methods like cell surface display and so on (Figure 2) [9]. However, phage display selection is the most commonly used strategy for this sort of screening, which is relatively fast to produce Nbs and has low cost, compared with the conventional polyclonal and monoclonal Abs.Nanobody selection based on naïve libraries takes advantage of the natural immunological diversity of the host animal without immunization [3,17]. Clearly, in any case, the success of this process depends on the amount of blood samples collected and it should be taken into account that only high specificity Abs can be obtained.

Other strategies from semisynthetic/ synthetic libraries

are based mainly on randomly varying the corresponding CDR

sequences to generate higher degree of diversity than when the

protocol performed depends on naïve libraries. Therefore, these

sorts of libraries are considered a promising alternative to the

conventional method including immunization of animals. Regarding

of Nanobody production, a wide range of different expression

models can be used including organisms such as bacteria, yeast,

fungi, insect cells, mammalian cells, or even plant hosts [18]. The

most widely used expression system is Escherichia coli, which

expresses proteins in different cellular compartments. The main

advantage of working with this expression host is that it enables

the production of soluble functional Nbs and that requires cheap

protocols. Conversely, the yields are not very high compared with

organisms such as yeast or fungi. Another usual way to produce Nbs

uses mammalian cells.

This is the most suitable choice when Nbs are produced for

therapeutic purposes, although their cost, long time requirements,

and complex handling do not make them the first option. Other

possible methods include the use of yeast and fungi, which have

already been successfully applied, but the production process is still

complex. Moreover, the fact that Nbs can be expressed in different

organisms is an advantage with respect to conventional mAb

production since it allows insertion of customized tags, production

at low cost, and high production scale [2]. Unlike the mAbs

production, which requires sophisticated machinery only found in

eukaryotic systems and uses very large mammalian cell cultures

and long screening and purification steps, leading to very expensive

production costs, Nbs are a good alternative to solve the problem

of mAb production costs. Nbs can be easily expressed in microbial

systems such as bacteria, yeasts, fungi 9 and rapidly screening

from display libraries. Moreover, using sequencing technologies, it

is particularly easier for high-throughput screenings. All of these

production and selection advantages result in lower manufacturing

prices.

Introduction to Molecular Imaging Technologies

The focus on the diagnosis of tumor imaging is just critical, as

the tumor’s antigen profiles obtained by visual imaging are essential

to maximize therapeutic efficacy. A variety of imaging modalities

are utilized in cancer diagnosis, and molecular imaging techniques

have shown potential in improving existing techniques [1]. Mainly,

there are two imaging techniques mentioned frequently, including

nuclear imaging technique and the optical imaging technique.

The nuclear techniques of PET and SPECT comprise the majority

of molecular imaging studies due to the advantages of their high

sensitivity, quantitative output, and clinical relevance. For tracking,

Nbs are tagged with a positron-emitting nuclide (e.g., 18F, 68Ga,

89Zr) for PET, and gamma-emitting nuclides (e.g., 99mTc) are

used for SPECT [1]. The optical imaging techniques, including

ultrasound, quantum dots, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI),

have also been studied with Nbs. Nbs tagged with fluorescent dyes,

offers the advantages of simplicity, flexibility, cost effectiveness, and

safety, although the technique has weaker penetration.

Ultrasound imaging utilizes reflected sound waves from tissues,

and Nbs have been tagged to contrast agents, microbubbles, and

nanobubbles. Even though it is a comparatively safer technique,

its applications are currently limited to systemic vasculature [19].

Quantum dots are fluorescent nanocrystals that have recently

demonstrated tumor imaging potential for their superior stability,

adaptable properties, and multiplex detection. However their low

biocompatibility limited their current implementation. Nanobodyconjugated

quantum dots targeting epidermal growth factor

receptor vIII (EGFRvIII) [20], carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) [21],

and cytotoxic T lymphocyteantigen-4 (CTLA-4) 22 have achieved

enhanced targeting with minimal toxicity in vivo [20,22]. MRI is a

more expensive technique that utilizes strong magnetic fields to

generate higher resolution images. Nbs coated magnetoliposomes

[23], super paramagnetic nanoparticles [24], and fluorescent

streptavidin [25] has paired with the technology for detecting

ovarian tumors.

Imaging Cancer Biomarkers Against by Nbs

Currently, Nbs against cancer biomarkers, such as human

epidermal growth factor receptor type 2 (HER2) are in clinical

testing [26-28]. HER2, an oncogene that encodes a transmembrane

tyrosine kinase receptor, is used as a classifier of invasive breast

cancer and a major therapeutic target. HER2 is over expressed

in 15-20% of patients with breast cancer [29-30]. Based on the

success of a phase I clinical trial of a 68Ga-HER2 nanobody that

could detect primary and metastatic tumors without adverse

effects [31], the phase II clinical trial was performed. Notably, the

HER2-CAIX combination synergistically enhanced the T/B ratio

and could also detect lung metastases [32]. Nbs targeting other

cancer biomarkers, such as a sepidermal growth factor receptor

hepatocyte growth factor [33], carcinoembryonic antigen [34] and

HER [35]. have been developed, radiolabeled and used in mouse

models. Notably, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) is a

marker associated with metastasis and immune evasion, and anti-

VCAM-1 nanobody microbubbles have been used for ultrasound

imaging of murine carcinomas [19].

Additionally, 89Zr-HER3 [35], 18F-HER2 [36], and 68Ga-NOTACD20

[37] Nbs, 99mTc-EGFR [38] 99mTc-EGFR-cartilage oligomeric

matrix protein (COMP) [39], 99mTc-dipeptidyl-peptidase-like

protein 6 (DPP6) [40], 99mTc-mesothelin [41], and 131I-HER2

[42] nanobody probes have also demonstrated high T/B ratios.

Additionally, anti-EGFR nanobody probes have been utilized in

dual-isotope SPECT [43] and optical imaging 44, with an enhanced

T/B ratio vs. mAb-based probes [44,45]. Other studies have

assessed nanobody probes targeting immune checkpoints (ICP)

CTLA-4 and programmed death ligand 1 (PDL1) [45] for nuclear

imaging with high T/B ratios [46,47] have demonstrated success

in various tumor models. An anti-human PD-L1 nanobody was

developed for non-invasively imaging [48], which can detect PD-L1

in melanoma and breast tumors and showed high signal-to-noise

ratios in tumors. Compared with immunohistochemistry, Wholebody

noninvasive imaging of PD-L1, is likely to be more informative,

which can provide visualization, localization and quantification of

its expression throughout the body.

The studies published recently about a 99mTc-labeled anti-

PD-L1 nanobody at an early phase I, showed that no drug-related

adverse events were observed. Tumor images with good signalto-

background ratios were obtained 2 h post injection and signal

was mainly detected in the kidneys, spleen, liver and bone marrow [49]. Overall, Nbs have proved to be excellent imaging agents to

assess the presence or absence of important cancer biomarkers

on metastatic lesions and primary tumors according to the results

shown from several preclinical [37,50,51] and early clinical imaging

studies [31,52].

Outlook

While we have focused mainly on image a range of infectious

diseases, Nbs, possessing the own advantageous physicochemical

properties, such as the high tolerance of Nbs against extreme pHs,

high temperatures and high concentrations of organic solvents

have opened a wide range of applications for the detection of small

molecule. Their nano-size enables enhanced tumor penetration

and access to hidden and/or intracellular epitopes, their stability

and manufacturing ease are favorable for large-scale production,

and their superior paratope diversity allows an extensive arsenal

for tumor antigen targeting. Nbs owning high sequence similarity

with human VH domains 52 possess low immunogenicity and

are appropriate for human administration. Combined with their

size, structure, low agglutination, coupling efficiency, tissue

penetrability and rapid renal clearance and no side effects, Nbs are

a real desirable for imaging purposes. Nbs can overcome some of

the limitations that first-generation Abs showed.

Using nanobody-based imaging probes has shown improved

visualization compared to traditional mAb-based probes. For high

affinity Nbs’ development, considering about the animal welfare,

semisynthetic/synthetic libraries have been used for producing

high affinity Nbs instead of the immune antibody library. However,

there are still more requirement of rational and faster panning

methods are applied to ensure the production of Nbs with the

feature of high affinity and selectivity. With several Nbs having

advanced to the clinic, and with FDA approval of one nanobodybased

drug, in addition to imaging applications of Nbs, we forecast

that, Nbs will be the leading actor to being developed as many

innovative and high potential molecules for cancer immuneimaging

and immunotherapy in the near future.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (ZR2020MC186). The contribution of the authors: Jinfang Yang, Guanggang Qu, Changjiang Wang: literature review and interpretation, manuscript writing, and final approval of manuscript. Haijing Zhang and Wenxiao Zhang provided the information of imaging techniques, conception and design and do the final approval of manuscript.

References

- Yang E Y, Shah K (2020) Nanobodies: Next Generation of Cancer Diagnostics and Therapeutics. Front Oncol 10: 1182.

- Salvador JP, Vilaplana L, Marco MP (2019) Nanobody: outstanding features for diagnostic and therapeutic applications. Anal Bioanal Chem 411(9): 1703-1713.

- Muyldermans S (2013) Nanobodies: natural single-domain antibodies. Annu Rev Biochem 82: 775-797.

- Steeland S, Vandenbroucke RE, Libert C (2016) Nanobodies as therapeutics: big opportunities for small antibodies. Drug Discov Today 21(7): 1076-113.

- Kubala MH, Kovtun O, Alexandrov K (2010) Structural and thermodynamic analysis of the GFP:GFP-nanobody complex. Protein Sci 19(12): 2389-2401.

- Hamers Casterman C, Atarhouch T, Muyldermans S, Robinson G, Hamers C, et al. (2993) Naturally occurring antibodies devoid of light chains. Nature 363(6428): 446-448.

- Muyldermans S, Baral TN, Retamozzo VC, De Baetselier P, De Genst E, et al. (2009) Camelid immunoglobulins and nanobody technology. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 128(1-3): 178-183.

- Vuchelen A, O'Day E, De Genst E, Pardon E, Wyns L, et al. (2009) (1)H, (13)C and (15)N assignments of a camelid nanobody directed against human alpha-synuclein. Biomol NMR Assign 3(2): 231-233.

- Liu W, Song H, Chen Q, Yu J, Xian M, et al. (2018) Recent advances in the selection and identification of antigen-specific nanobodies. Mol Immunol 96: 37-47.

- Davies J, Riechmann L (1996) Single antibody domains as small recognition units: design and in vitro antigen selection of camelized, human VH domains with improved protein stability. Protein Eng 9(6): 531-537.

- Arbabi Ghahroudi M, Desmyter A, Wyns L, Hamers R, Muyldermans S, et al. (1997) Selection and identification of single domain antibody fragments from camel heavy-chain antibodies. FEBS Lett 414(3): 521-526.

- Perez JM, Renisio JG, Prompers JJ, van Platerink CJ, Cambillau C, et al. (2001) Thermal unfolding of a llama antibody fragment: a two-state reversible process. Biochemistry 40(1): 74-83.

- Wang J, Bever CR, Majkova Z, Dechant JE, Yang J, et al. (2004) Heterologous antigen selection of camelid heavy chain single domain antibodies against tetrabromobisphenol A. Anal Chem 86(16): 8296-8302.

- Dumoulin M, Conrath K, Van Meirhaeghe A, Meersman F, Heremans K, et al. (2002) Single-domain antibody fragments with high conformational stability. Protein Sci 11(3): 500-515.

- Conrath KE, Lauwereys M, Galleni M, Matagne A, Frere JM, et al. (2001) Beta-lactamase inhibitors derived from single-domain antibody fragments elicited in the camelidae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45(10): 2807-2812.

- Lauwereys M, Arbabi Ghahroudi M, Desmyter A, Kinne J, Holzer W, et al. (1998) Potent enzyme inhibitors derived from dromedary heavy-chain antibodies. EMBO J 17(13): 3512-3520.

- Wang Y, Fan Z, Shao L, Kong X, Hou X, et al. (2016) Nanobody-derived nanobiotechnology tool kits for diverse biomedical and biotechnology applications. Int J Nanomedicine 11: 3287-303.

- Liu, Y, Huang H (2018) Expression of single-domain antibody in different systems. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 102(2): 539-551.

- Hernot S, Unnikrishna S, Du Z, Shevchenko T, Cosyns B (2012) Nanobody-coupled microbubbles as novel molecular tracer. J Control Release 158(2): 346-353.

- Fatehi D, Baral TN, Abulrob A (2014) In vivo imaging of brain cancer using epidermal growth factor single domain antibody bioconjugated to near-infrared quantum dots. J Nanosci Nanotechnol 1(7): 5355-5362.

- Sukhanova A, Even-Desrumeaux K, Kisserli A, Tabary T, Reveil B, et al. (2012) Oriented conjugates of single-domain antibodies and quantum dots: toward a new generation of ultrasmall diagnostic nanoprobes. Nanomedicine 8(4): 516-525.

- Wang W, Hou X, Yang X, Liu A, Tang Z, et al. (2019) Highly sensitive detection of CTLA-4-positive T-cell subgroups based on nanobody and fluorescent carbon quantum dots. Oncol Lett 18(1): 109-116.

- Khaleghi S, Rahbarizadeh F, Ahmadvand D, Hosseini HRM (2017) Anti-HER2 VHH Targeted Magnetoliposome for Intelligent Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Breast Cancer Cells. Cell Mol Bioeng 10(3): 263-272.

- Shahbazi-Gahrouei D, Abdolahi M (2013) Detection of MUC1-expressing ovarian cancer by C595 monoclonal antibody-conjugated SPIONs using MR imaging. ScientificWorldJournal, pp. 609151.

- Prantner AM, Yin C, Kamat K, Sharma K, Lowenthal AC, et al. (2018) Molecular Imaging of Mesothelin-Expressing Ovarian Cancer with a Human and Mouse Cross-Reactive Nanobody. Mol Pharm 15(4): 1403-1411.

- Ulaner GA, Hyman DM, Ross DS, Corben A, Chandarlapaty S, et al. (2016) Detection of HER2-Positive Metastases in Patients with HER2-Negative Primary Breast Cancer Using 89Zr-Trastuzumab PET/CT. J Nucl Med 57(10): 1523-1528.

- Dijkers EC, Oude Munnink TH, Kosterink JG, Brouwers AH, Jager PL (2010) Biodistribution of 89Zr-trastuzumab and PET imaging of HER2-positive lesions in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Clin Pharmacol Ther 87(5): 586-592.

- Tamura K, Kurihara H, Yonemori K, Tsuda H, Suzuki J, et al. (2013) 64Cu-DOTA-trastuzumab PET imaging in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer. J Nucl Med 54(11): 1869-1875.

- Ross, JS, Slodkowska EA, Symmans WF, Pusztai L, Ravdin PM (2009) The HER-2 receptor and breast cancer: ten years of targeted anti-HER-2 therapy and personalized medicine. Oncologist 14(4): 320-368.

- Wolff AC, Hammond ME, Hicks DG, Dowsett M, McShane LM (2014) American Society of Clinical, O.; College of American, P., Recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists clinical practice guideline update. Arch Pathol Lab Med 138(2): 241-256.

- Keyaerts M, Xavier C, Heemskerk J, Devoogdt N, Everaert H, et al. (2016) Phase I Study of 68Ga-HER2-Nanobody for PET/CT Assessment of HER2 Expression in Breast Carcinoma. J Nucl Med 57(1): 27-33.

- Kijanka MM, van Brussel AS, van der Wall E, Mali WP, van Diest PJ, et al. (2016) Optical imaging of pre-invasive breast cancer with a combination of VHHs targeting CAIX and HER2 increases contrast and facilitates tumour characterization. EJNMMI Res 6(1): 14.

- Vosjan MJ, Vercammen J, Kolkman JA, Stigter-van Walsum M (2012) Nanobodies targeting the hepatocyte growth factor: potential new drugs for molecular cancer therapy. Mol Cancer Ther 11(4): 1017-1025.

- Vaneycken I, Govaert J, Vincke C, Caveliers V, Lahoutte T, et al. (2010) In vitro analysis and in vivo tumor targeting of a humanized, grafted nanobody in mice using pinhole SPECT/micro-CT. J Nucl Med 51(7): 1099-106.

- Warnders F, Terwisscha van Scheltinga AGT, Knuehl C, van Roy M, de Vries EFJ (2017) Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 3-Specific Tumor Uptake and Biodistribution of (89)Zr-MSB0010853 Visualized by Real-Time and Noninvasive PET Imaging. J Nucl Med 58(8): 1210-1215.

- Zhou Z, McDougald D, Devoogdt N, Zalutsk MR, Vaidyanathan G (2019) Labeling Single Domain Antibody Fragments with Fluorine-18 Using 2,3,5,6-Tetrafluorophenyl 6-[(18)F]Fluoronicotinate Resulting in High Tumor-to-Kidney Ratios. Mol Pharm 16(1): 214-226.

- Krasniqi A, D'Huyvetter M, Xavier C, Van der Jeught K, Muyldermans S, et al. (2017) Theranostic Radiolabeled Anti-CD20 sdAb for Targeted Radionuclide Therapy of Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. Mol Cancer Ther 16 (12): 2828-2839.

- Gainkam LO, Caveliers V, Devoogdt N, Vanover C, Xavier C, et al. (2011) Localization, mechanism and reduction of renal retention of technetium-99m labeled epidermal growth factor receptor-specific nanobody in mice. Contrast Media Mol Imaging 6(2): 85-92.

- Li C, Feng H, Xia X, Wang L, Gao B, et al. (2016) (99m) Tc-labeled tetramer and pentamer of single-domain antibody for targeting epidermal growth factor receptor in xenografted tumors. J Labelled Comp Radiopharm 59(8): 305-312.

- Balhuizen A, Massa S, Mathijs I, Turatsinze JV, De Vos, et al. (2017) A nanobody-based tracer targeting DPP6 for non-invasive imaging of human pancreatic endocrine cells. Sci Rep 7(1): 15130.

- Montemagno C, Cassim S, Trichanh D, Savary C, Pouyssegur J, et al. (2019) (99m)Tc-A1 as a Novel Imaging Agent Targeting Mesothelin-Expressing Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 11(10): 1531.

- D'Huyvetter M, De Vos J, Xavier C, Pruszynski M, Sterckx YGJ et al. (2017) (131)I-labeled Anti-HER2 Camelid sdAb as a Theranostic Tool in Cancer Treatment. Clin Cancer Res 23(21): 6616-6628.

- Beltran Hernandez I, Rompen R, Rossin R, Xenaki KT, Katrukha EA, et al. (2019) Imaging of Tumor Spheroids, Dual-Isotope SPECT, and Autoradiographic Analysis to Assess the Tumor Uptake and Distribution of Different Nanobodies. Mol Imaging Biol 21(6): 1079-1088.

- Oliveira S, van Dongen GA, Stigter-van Walsum M, Roovers RC, Stam JC, et al. (2012) Rapid visualization of human tumor xenografts through optical imaging with a near-infrared fluorescent anti-epidermal growth factor receptor nanobody. Mol Imaging 11(1): 33-46.

- Li D, Cheng S, Zou S, Zhu D, Zhu T, et al. (2018) Immuno-PET Imaging of (89) Zr Labeled Anti-PD-L1 Domain Antibody. Mol Pharm 15(4): 1674-1681.

- Ingram, JR, Blomberg OS, Rashidian M, Ali L, Garforth S, et al. (2018) Anti-CTLA-4 therapy requires an Fc domain for efficacy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115(15): 3912-3917.

- Rashidian M, Keliher E, Dougan M, Juras PK, Cavallari M, et al. (2015) The use of (18)F-2-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) to label antibody fragments for immuno-PET of pancreatic cancer. ACS Cent Sci 1(3):142-147.

- Broos K, Lecocq Q, Xavier C, Bridoux J, Nguyen TT, et al. (2019) Evaluating a Single Domain Antibody Targeting Human PD-L1 as a Nuclear Imaging and Therapeutic Agent. Cancers (Basel) 11(6): 872.

- Xing Y, Chand G, Liu C, Cook GJR, O’Doherty J, et al. (2019) Early Phase I Study of a (99m) Tc-Labeled Anti-Programmed Death Ligand-1 (PD-L1) Single-Domain Antibody in SPECT/CT Assessment of PD-L1 Expression in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. J Nucl Med 60 (9): 1213-1220.

- Evazalipour M, D'Huyvetter M, Tehrani BS, Abolhassani M, Omidfar K, et al. (2014) Generation and characterization of nanobodies targeting PSMA for molecular imaging of prostate cancer. Contrast Media Mol Imaging 9(3): 211-220.

- Chatalic KL, Veldhoven-Zweistra J, Bolkestein M, Hoeben S, Koning GA, et al. (2015) A Novel ¹¹¹In-Labeled Anti-Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen Nanobody for Targeted SPECT/CT Imaging of Prostate Cancer. J Nucl Med 56(7): 1094-1099.

- Klarenbeek A, El Mazouari K, Desmyter, A, Blanchetot C, Hultberg A, et al. (2015) Camelid Ig V genes reveal significant human homology not seen in therapeutic target genes, providing for a powerful therapeutic antibody platform. MAbs 7(4): 693-706.

Review Article

Review Article