Abstract

Objective: To analyze the perception of quality of life of people with kidney

transplantation and kidney transplant candidates treated at the High Specialty Medical

Unit of Mérida.

Materials and Methods: qualitative study with interpretative phenomenological

approach, intentional sampling, the final sample was made up of 11 people with a

history of CKD: 7 candidates to receive kidney transplantation and 4 transplanted; data

were collected through semi-structured interviews conducted during their follow-up

consultations which were analyzed through content analysis.

Results: The categories analyzed were concept of quality of life with its domains:

physical, economic, family, and social. Most of the participants said that quality of life is

to be well physically, mentally, and emotionally, as well as to have all the basic services

and not depend on renal replacement treatments: dialysis or hemodialysis.

Conclusions: A perception of absolute quality of life or free of discomfort is

not achieved and human responses that require care and interventions to achieve

the highest level of well-being are still manifested. The construction of the concept

of quality of life includes physical, mental, personal, and social elements feasible to

document and in which to exercise interventions for the benefit of the people treated

and their families, it is evident that human responses do not only obey physiological

needs.

Keywords: Perception; Quality of Life; People; Kidney Transplant; Kidney Diseases. DeCS

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) affects around 11% of the

population over the age of 20 globally, with an increase in

incidence in recent years [1]. Peritoneal dialysis, hemodialysis and

kidney transplantation are treatments that have been effective in

increasing the life expectancy of people with CKD [1,2]. In the last

three decades, the analysis of quality of life has been integrated as

an indicator of the evolution of health status in patients with CKD

to see beyond the number of years of survival. Quality of life is,

according to the WHO, “the perception that an individual has of his

place in existence, in the context of the culture and value system

in which he lives and in relation to his objectives, his expectations,

his norms, his concerns. It is a concept that is influenced by the

physical health of the subject, their psychological state, their

level of independence, their social relationships, as well as their

relationship with the environment.” This concept encompasses

objective and subjective aspects that reflect the degree of physical,

emotional, social and economic well-being of each individual. The analysis of the quality of life in people with CKD allows us to

understand the impact of the disease and its treatment, to know

more about patients, how they evolve and how they adapt to

organic alteration [3,4]. Currently, the analysis of quality of life

in people with CKD seeks to generate evidence, qualitative and

quantitative, to facilitate: the process of assessing human needs and

the implementation of quality interventions in the care sectors [5].

In the health sciences, phenomenological research, and those with

a qualitative approach in general, generate evidence that serves as

a guide to practice sensitive to the realities of the people to whom

care is directed, to their cultural diversity and to the contexts in

which their lives unfold [6,7].

In studies related to quality of life in transplanted people

and candidates for kidney transplantation, participants manifest

as the main human responses: recurrent hospitalizations,

uncertainty about the work situation, deterioration of body image,

deterioration of sexual functionality, dependence on third parties,

stress and guilt [2,8-12]. Specifically, people who are candidates

for kidney transplantation manifest as the main human responses:

anxiety and depression [13,14]. Transplanted individuals report

acute rejections, medication side effects, and emotional instability;

[12-15,16] immediately, after transplantation, they may perceive

release with respect to dependence on renal replacement therapy,

but as time goes by, they have to face various adaptation problems:

side effects of medications, medical and social complications, among

the latter the return to work, social and family life [12,16,17]. The

analysis of quality of life, with its respective components and human

responses in patients with a history of CKD is recent. Therefore, the

needs inherent in the nursing care process may go unnoticed when

directing care for people with these characteristics. Although there

are numerous studies that quantitatively address health-related

quality of life, [4,18,19] qualitative studies such as the present

one provides particular evidence to integrate it into the holistic

process of the nursing-patient relationship at different levels of

care [13,20]. Therefore, the objective of this study is to analyze the

perception of quality of life of people with kidney transplantation

and kidney transplant candidates treated at the High Specialty

Medical Unit of Mérida, to identify the related human responses

through an interpretive phenomenological approach.

Methodology

Design

A qualitative study was conducted with an interpretative phenomenological approach. From this design it is possible to reach the understanding of the experiences and the articulation of similarities and differences in the meanings and human experiences of people with kidney transplantation and candidates for kidney transplantation. Although it is not possible to make generalizations of the results of this study, particular data are reached with transferability to other populations with similar characteristics [6,7,14]. This article followed the COREQ [Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research] criteria to enhance its quality and clarity [21].

Study and Sampling Population

An intentional sampling was carried out, obtaining a final sample consisted of 11 people with a history of ERD: 7 candidates to receive kidney transplant and 4 transplanted, who received health services in the High Specialty Medical Unit of Mérida [UMAE] of the Mexican Institute of Social Security [IMSS]during the period from November 2019 to February 2020.

Data Collection

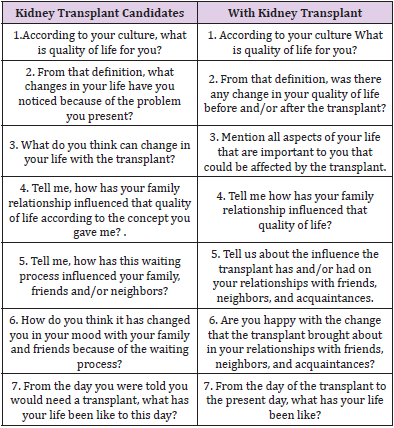

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews conducted during their follow-up consultations. Interviews lasted 30 to 40 minutes, were recorded in audio format, and field notes were taken. Table 1 presents the questions asked during the semistructured interviews.

Ethical Considerations

The study respects ethical principles: beneficence, nonmaleficence, justice and autonomy. The research study protocol, with folio R-2018-785-129, was approved by the ethics committee of the High Specialty Medical Unit of the Mexican Social Security Institute. The testimonies presented herein are referenced with codes to safeguard the identity of the participants.

Information Processing

Semi-structured interviews were transcribed verbatim and then

analyzed using content analysis. This analysis process consisted of:

1. Encoding the data and establishing a data index.

2. Categorize the content of the data into meaningful categories;

and

3. Determine the topics related, in this case human responses, to

the previously defined categories [7,22]. In the results section,

tables are presented that allow to visualize the categories of

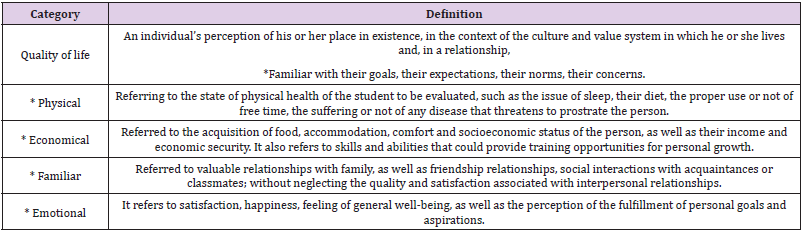

analysis delimited in Table 2 from Urzúa and Caqueo [23],

the human responses within the categories and, finally,

testimonies of the participants; all of the above accompanied

by interpretive narrative.

Table 2: Number, crude and age-standardized rate per 100,000 by sex and time during 2005-2014 in the Nghe An province.

Note: * Categories of the concept of quality of life from Urzúa and Caqueo.

Quality Criteria

Once the transcript of the interviews was completed, the 11 participants were asked to verify that the information interpreted was correct. Also the protocolization related to the organization of the data, the detailed and meticulous description of the selection of the sample and the context in which the study is carried out, facilitate the possibility of transfer and reproducibility of the same in similar conditions, thus providing another criterion of qualitative quality.

Results

Characteristics of the participants Years of age were a median of 37 [mean 39]and SD=13 in the 11 participants. In people who were candidates for RT, the median was 37 [mean 41]and in those with RT it was 35.7 years [mean 41), respectively. In the latter group two people were 6 months or less old after receiving RT, one was 1 year old, and one person was 10 years old. Table 3 shows that the majority of the total sample was made up of men who worked as employees.

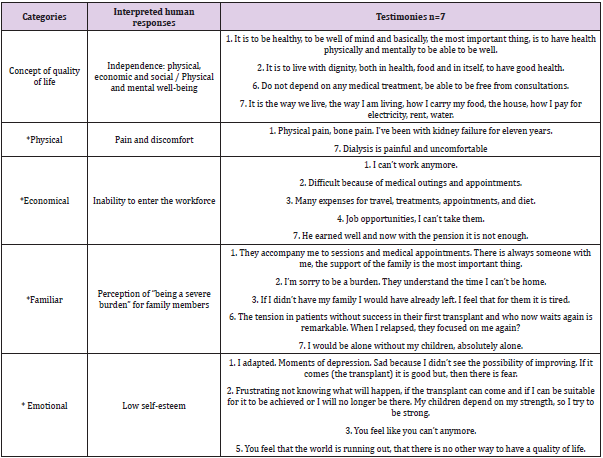

Quality of Life: Perception in Kidney Transplant Candidates

Table 4 shows the interpretations related to the categories: concept of quality of life with their respective domains: physical, economic, family, and social, then the identified human responses are presented. Most of the participants said that quality of life is to be well physically, mentally, and emotionally, as well as to have all the basic services and not depend on renal replacement treatments: dialysis or hemodialysis. In the physical domain, people highlight discomfort, pain and discomfort related to the procedures of renal replacement therapies or the body itself: chronic or bone pain, for example, these human responses largely condition the inability to enter the labor field. In the economic domain, the participants report that they are unable to carry out the activities of any employment due to physical disability, and therefore, consider that their monetary income from a trade or employment is limited, scarce or null. In addition, they stressed that the economic resources are focused on financing the management of the health itself: laboratory tests, transportation, extraordinary treatments, appointments, and medical consultations, among others; these efforts are complicated precisely by the lack of monetary inputs.

Table 4: Quality of life: perception of kidney transplant candidates.

Note: *Categories of the concept of quality of life from Urzúa and Caqueo.

In the family domain, people identify the importance of the support, care, and understanding they receive, received, and expect to receive from their family in the ups and downs related to their state of health and well-being. In this regard, some express feelings of feeling a burden for their relatives for the extra activities that the latter perform in health management, which generates tension and uncertainty. However, the interviewees expressed the motivation generated by their family environment: mothers, children and grandchildren, among other ties, drive the desire to want to get out of their problem and be patients waiting for the transplant. In the emotional domain, each of the people interviewed expressed their affectation at different points that leads them to present low self-esteem: fear, frustration, depression, sadness and uncertainty are some of the emotions they expressed among their testimonies. Participants follow a continuous coping process, because not every day they feel with all the energy and motivation to continue with everyday life. The emotional perception of the interviewees was reflected in their features during the interviews, they touched points that led them to cry, they expressed how difficult it is to live with a dysfunctional organ, the uncertainty before the latent complications that can even make them lose their lives.

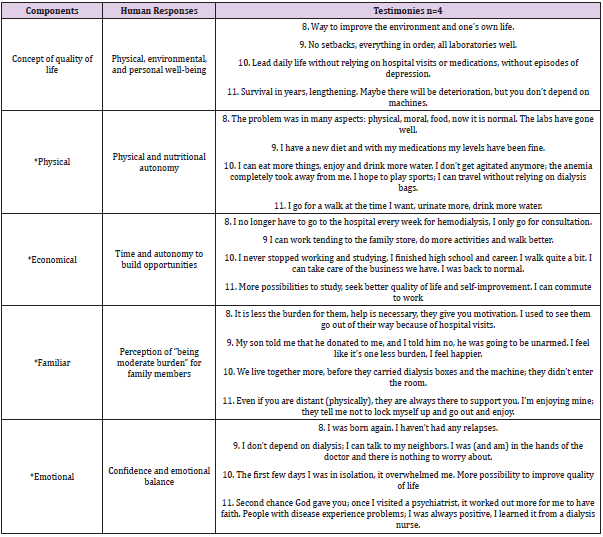

Quality of life: Perception in People with Kidney Transplantation

Table 5 shows that most participants consider that quality of life involves physical, environmental and personal well-being as components. For one of the interviewees, it means no longer relying on external factors to sustain life; another considered that the longer he can extend his life is better for the quality of it, considered that discomforts are companions of life. In the physical domain, the interviewees expressed the freedom to perform various activities and eat food without affecting their quality of life. They expressed that they could move and travel without thinking about the need to carry too many supplies related to their treatment. They also stated that they can eat food without causing discomfort or altering their clinical parameters, especially water, which was previously restricted. In the economic domain, participants report that they have time and autonomy to build opportunities for insertion into trades, jobs and vocational or educational training. One case mentioned that the ability to acquire economic resources improves their quality of life, another participant reports that they can work freely without thinking about the times of some renal therapy, finally, a case refers that they returned to normal by fully taking these opportunities that they previously addressed discreetly.

Table 5: Quality of life: perception of kidney transplants.

Note: *Categories of the concept of quality of life from Urzúa and Caqueo.

In the family domain, the perception and feelings of being considered a burden on their families has decreased along with the amount of care related to renal replacement therapies from which transplanted participants are already exempt; people mentioned that despite the constant support of their relatives there was a physical distancing seeking to reduce the crossing of infections, a situation that in recent times has ended and they can share more time and experiences together. In the emotional domain, trust and emotional balance were interpreted in the participants. Two people mentioned that they feel they have a new opportunity before life, to restart it and have new experiences that they previously did not consider possible. Two people referred to the need to have confidence and know how to take the advice of health personnel: doctors and nurses. Finally, one participant described that he was overwhelmed by living a few days in isolation after his transplant, necessary to prevent infections, but at the same time accepts that it is necessary to improve his quality of life.

Discussion

The quality of life of people with a history of renal pathologies is

affected since the first clinical manifestations, the QoL in this sector

has shown deficiencies, low levels or areas of opportunity with

respect to the rest of the population [24]. Physical, environmental

and personal well-being are part of the conception of quality of

life in people with renal pathologies, whether they have been

transplanted or not. In the early stages of the disease there are

a series of negative perceptions of the disease and its mediate

and immediate quality of life that, ultimately, can influence their

coping actions, these perceptions can trigger anxiety, depression,

coping, autonomy, self-esteem and accelerated progression of

the disease [25]. In the identification of human responses in

patients with chronic kidney disease, the main physiological

risks related to this pathology have been highlighted. Farias et. al.

points out the overstating of biological and complication-related

human responses by nursing staff providing care to patients

with nephropathies in a renal center. Among 24 diagnostic labels

identified, the most frequent were “risk of infection”, “excess fluid

volume”, “hypothermia”, among others whose main domains were

located in Safety / Protection and Activity / Rest, on the other

hand, “low situational self-esteem” was ranked 16th in frequency

[26] corresponding to the Self-perception domain in the NANDA-I

[20]. The above shows what Spilogon et. al. points out as an area of

opportunity in the nursing process because it has the flexibility and

openness to consider the perceptions and preferences of the user,

in this case of the patient with nephropathies [27].

In the emotional category, low self-esteem was detected in

participants with CKD without transplantation, and that is that

a patient with CKD has needs for recognition and esteem, so the

people in charge of their care should promote favorable behaviors

in coping with the pathology and attachment to treatment, avoiding

judging and repressing the failures of our human condition [28].

In contrast, participants who had received a kidney transplant

manifested confidence and emotional balance, something that

could be considered normal after receiving the expected transplant

according to Tucker, et. al. [29]. From a quantitative approach

Rocha et. Al. point out that the higher the quality of life, the better

the assessment of the self-esteem of people with chronic kidney

disease after transplantation [30].

In the economic category, while people who had not received

kidney transplantation conceived the inability to enter the

workforce among their perception of quality of life, those who

had received kidney transplantation indicated greater time and

autonomy to build job and academic opportunities. Reports

indicate that patients with chronic kidney disease face many

barriers to staying or joining the workforce after starting dialysis:

limited opportunities, lack of financial resources to invest, fatigue

and other symptoms of kidney failure, potential loss of disability

benefits or medical follow-up, dialysis scheduling, and employer

bias. The societal perception that patients with CKD cannot work

completes a vicious cycle of low employment expectations [25,31].

In the family category, the perception of “being a burden” for

family members influences is an important component in the

perception of the quality of life of people with transplantation and

without kidney transplantation. Evidence indicates that family

members of patients with a history of renal pathologies manifest

sleep interruptions, depression, anxiety, among other disorders

associated with unforeseen responsibilities related to the treatment

and logistics of their relatives; they must also deal with insufficient

information, medication regimen and be accompanied by periodic

hospitalizations [32]. NANDA International classifies problems into

plausible diagnostic labels of interventions focused on promoting

the health of individuals, the family. and community, we can

mention: Risk of fatigue of the role of caregiver, Fatigue of the role

of the caregiver, Dysfunctional family processes, Willingness to

improve family processes, among others [20].

In the physical category, participants without kidney

transplantation are identified as a condition for quality of life, a

common and often severe manifestation in various populations

with CKD; with prevalence’s of 40% to 60% is a strong imperative

to establish the management of chronic pain as a clinical and

research priority [33]. In this regard, the labels acute and chronic

pain are available in NANDA-I [20]. Although pain and physical

limitation decreases after a kidney transplant, it is important to

mention that the physical and nutritional autonomy indicated by

the participants of the present can generate an excess of confidence

and the acquisition of unhealthy practices. Physical training

regulated by physiotherapy specialists appears to be safe in kidney transplant recipients and is associated with improved quality of life

and exercise capacity [34]. With respect to diet, the Mediterranean

and DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diets have

been shown to be the most beneficial dietary patterns for the

population after kidney transplantation by focusing on less meat

and processed foods, while increasing intake of fresh foods and

plant-based options. [35]. Knowledge and awareness in the renal

transplant population should be a cornerstone of therapy and an

integral part of nursing responsibilities. Therefore, nurses should

educate patients about self-care behaviors and remind them of the

dangerous complications of abandoning them [28].

In participants who had not received a kidney transplant, there

was an expectation of receiving a kidney transplant to improve

their quality of life and from it to improve their quality of life. In

this aspect we can mention the benefits before the expectation of

receiving a kidney transplant mentioned by Santos et. al. who in a

group of people with Brazilian nephropathies detected that patient

who were not waiting for transplantation were at risk of poor

quality of life, mainly in the emotional and physical aspects; those

who were not awaiting transplantation died more frequently in the

next 12 months [36]. However, betting on kidney transplantation

to improve the quality of life in patients with nephropathies is not

entirely recommended, in this regard we can cite the studies of

Schulz et. al. and Smith et. al. published in 2014 and 2019, [29,37]

who reported that before transplantation patients can overestimate

gains in quality of life without finding significant improvements in

quality of life after being transplanted.

Kidney transplantation is not a guarantee of improvement in

quality of life in all patients with nephropathies, in the present

study, those people who had received the kidney transplant did

not consider an absolute improvement in their quality of life. The

literature notes that kidney transplants can provide dramatic

improvements in quality of life and health status, however, the effects

on improvement are not universal and patients live in constant

uncertainty as they are aware of the likelihood of graft dysfunction

[29]. There are samples that have indicated that the expectation

about the functionality or rejection of the graft generates greater

fear and uncertainty than death itself [38]. The results on the

perception of quality of life in people receiving renal replacement

therapy support the trend of the last decade focused on the analysis

of this category beyond only assessing life expectancy [39]. The

limitations of the present are the risk of bias due to the same

interpretative approach and the inability to generalize the results

to the study population. To compensate for the above, criteria of

methodological rigor were followed and from a particular context

the search for generalities was made, reinforcing the results with

respect to other studies [21].

Conclusion

In transplant patients, a perception of absolute or discomfortfree quality of life is not achieved and human responses that require care and interventions to achieve the highest level of well-being are still manifested. The construction of the concept of quality of life includes physical, mental, personal and social elements feasible to document and in which to exercise interventions for the benefit of the people treated and their families, it is evident that human responses do not only obey physiological needs.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest with any institution/organization.

References

- Webster AC, Nagler EV, Morton RL, Masson P (2021) Chronic Kidney Disease. The Lancet. Lancet Publishing Group 389: 1238-1252.

- Sitjar-Suñer M, Suñer-Soler R, Masià-Plana A, Chirveches-Pérez E, Bertran-Noguer C, et al. (2020) Quality of Life and Social Support of People on Peritoneal Dialysis: Mixed Methods Research. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(12): 4240.

- Li Z, Zhang Y, Zhang L (2017) Evolution and future trends of integrated health care: a scientometric analysis. Int J Integr Care 17(5).

- Rebollo-Rubio A, Morales-Asencio JM, Pons-Raventos ME, Mansilla-Francisco JJ (2015) Revisión de estudios sobre calidad de vida relacionada con la salud en la enfermedad renal crónica avanzada en Españ Nefrologia 35(1): 92-109.

- Singh B, Rochow N, Chessell L, Wilson J, Cunningham K, et al. (2018) Gastric Residual Volume in Feeding Advancement in Preterm Infants (GRIP Study): A Randomized Trial. J Pediatr 200: 79-83.e1.

- Expósito Concepción MY, Villarreal Cantillo E, Palmet Jiménez MM, Borja González JB, Segura Barrios IM, et al. (2019) La fenomenología, un método para el estudio del cuidado humanizado. Rev Cuba Enfermería 35(1) Enero-Marzo.

- Rodriguez A, Smith J (2018) Phenomenology as a healthcare research method. Evid Based Nurs [Internet] 21(4):118.

- Moya Ruiz MA (2017) Estudio del estado emocional de los pacientes en hemodiá Enferm Nefrol 20(1): 48-56.

- Rodr C (2008) Calidad de vida en pacientes nefrópatas con terapia dialítica* 13(1): 15-22.

- Ottaviani AC, Souza ÉN, Drago N de C, de Mendiondo MSZ, Pavarini SCI, et al. (2014) Esperança e espiritualidade de pacientes renais crônicos em hemodiálise: Estudo correlacional. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem 22(2): 248-254.

- Jiménez Ocampo VF, Giraldo BP, Del Pilar Botello Reyes A (2016) Spiritual perspective and health-related quality of life of dialyzed patients. Rev Nefrol Dial y Traspl 36(2): 91-98.

- Gumabay FM, Novak M, Bansal A, Mitchell M, Famure O, et al. (2018) Pre-transplant history of mental health concerns, non-adherence, and post-transplant outcomes in kidney transplant recipients. J Psychosom Res 105: 115-124.

- Gómez Tovar LO, Díaz Suarez L, Cortés Muñoz F (2016) Cuidados de enfermería basados en evidencia y modelo de Betty Neuman, para controlar estresores del entorno que pueden ocasionar delirium en unidad de cuidados intensivos. Enfermería Global. Scieloes 15: 49-63.

- Cuesta Benjumea C de la (2010) La investigación cualitativa y el desarrollo del conocimiento en enfermerí Texto & Contexto- Enfermagem. Scielo 19: 762-766.

- Baines LBS, Joseph JT, Jindal RM (2002) Emotional issues after kidney transplantation: A prospective psychotherapeutic study. Clin Transplant 16(6): 455-460.

- De Pasquale C, Luisa Pistorio M, Veroux M, Indelicato L, Biffa G, et al. (2020) Psychological and psychopathological aspects of kidney transplantation: A systematic review. Front Psychiatry 11: 1.

- Müller HH, Englbrecht M, Wiesener MS, Titze S, Heller K, et al. (2015) Depression, anxiety, resilience and coping pre and post kidney transplantation - Initial findings from the psychiatric impairments in kidney transplantation (PI-KT)-study. PLoS One (11): e0140706.

- (2017) Asso-Soto ME P-MMC-EJ. Calidad de vida y perspectiva espiritual de los pacientes hospitalizados con enfermedad cardiovascular. Rev Enferm IMSS 25(2): 9-17.

- Saboya PP, Bodanese LC, Zimmermann PR, Da Silva Gustavo A, Assumpção CM, et al. (2016) Síndrome metabólica e qualidade de vida: Uma revisão sistemá Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem. University of Sao Paulo, Ribeirao Preto College of Nursing Organisation 24.

- Herdman HT, Kamitsuru S (2017) NANDA International Nursing Diagnoses: Definitions & Classification 2018-2020. Novena, editor. Michigan: Thieme.

- Walsh S, Jones M, Bressington D, McKenna L, Brown E, et al. (2020) Adherence to COREQ Reporting Guidelines for Qualitative Research: A Scientometric Study in Nursing Social Science, p. 19.

- Reeson M (2020) Phenomenological research in health professions education: Methods, Data collection and Analysis.

- Urzúa MA, Caqueo-Urízar A (2012) Calidad de vida: Una revisión teórica del concepto. Terapia psicoló Scielocl 30: 61-71.

- Sánchez-Cabezas AM, Morillo-Gallego N, Merino-Martínez RM, Crespo-Montero R, Sánchez-Cabezas AM, et al. (2019) Calidad de vida de los pacientes en diá Revisión sistemática. Enfermería Nefrológica 22(3): 239-255.

- Clarke AL, Yates T, Smith AC, Chilcot J (2016) Patient’s perceptions of chronic kidney disease and their association with psychosocial and clinical outcomes: a narrative review. Clin Kidney J 9(3): 494.

- Farias de Queiroz Frazão CM, de Almeida Medeiros AB, Mariano Nunes de Paiva M das G, Cruz Enders B, de Oliveira Lopes MV, (2015) Nursing diagnoses and adaptation problems among chronic renal patients. Investigación y Educación en Enfermerí Scieloco 33: 119-127.

- Spigolon DN, Teston EF, Souza F de O, Santos B dos, Souza RR de, et al. (2018) Nursing diagnoses of patients with kidney disease undergoing hemodialysis: a cross-sectional study. Rev Bras Enferm 71(4): 2014-2020.

- Poorgholami F, Javadpour S, Saadatmand V, Jahromi MK (2016) Effectiveness of Self-Care Education on the Enhancement of the Self-Esteem of Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis. Glob J Health Sci 8(2): 132.

- Tucker EL, Smith AR, Daskin MS, Schapiro H, Cottrell SM, et al. (2019) Life and expectations post-kidney transplant: a qualitative analysis of patient responses. BMC Nephrol 20(1).

- Rocha FL da, Echevarría-Guanilo ME, Silva DMGV da, Gonçalves N, Lopes SGR, et al. (2020) Relationship between quality of life, self-esteem and depression in people after kidney transplantation. Rev Bras Enferm 73(1): e20180245.

- Al-Rabiaah A, Temsah M-H, Al-Eyadhy AA, Hasan GM, Al-Zamil F, et al. (2020) Middle East Respiratory Syndrome-Corona Virus (MERS-CoV) associated stress among medical students at a university teaching hospital in Saudi Arabia. J Infect Public Health 13(5): 687-691.

- Nicole De Pasquale, Ashley Cabacungan, Patti L Ephraim, LaPricia Lewis-Boyér, Neil R Powe, et al. (2019) Family Members’ Experiences With Dialysis and Kidney Transplantation. Kidney Med 1(4): 171-179.

- Davison SN, Rathwell S, Ghosh S, George C, Pfister T, et al. (2021) The Prevalence and Severity of Chronic Pain in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis 8.

- Ashley Takahashi, Susie L Hu, Andrew Bostom (2018) Physical Activity in Kidney Transplant Recipients: A Review. Am J Kidney Dis 72(3): 433-443.

- Goldfarb Cyrino L, Galpern J, Moore L, Borgi L, Riella LV (2021) A Narrative Review of Dietary Approaches for Kidney Transplant Patients. Kidney Int Reports 6(7): 1764-1774.

- Paulo Roberto Santos (2011) Comparison of quality of life between hemodialysis patients waiting and not waiting for kidney transplant from a poor region of Brazil. J Bras Nefrol 33(2): 166-172.

- Schulz T, Niesing J, Homan van der Heide JJ, Westerhuis R, Ploeg RJ, et al. (2014) Great expectations? Pre‐transplant quality of life expectations and distress after kidney transplantation: A prospective study. Br J Health Psychol 19(4): 823-838.

- Howell M, Wong G, Rose J, Tong A, Craig JC, et al. (2017) Patient preferences for outcomes after kidney transplantation: a best-worst scaling survey. Transplantation 101(11): 2765-2773.

- Maglakelidze N, Pantsulaia T, Tchokhonelidze I, Managadze L, Chkhotua A (2011) Assessment of health-related quality of life in renal transplant recipients and dialysis patients. Transplant Proc 43(1): 376-369.

Research Article

Research Article