Abstract

Thoracic endometriosis is characterized by the presence of endometrial-like glands and stroma within the lung parenchyma or on the diaphragm and pleural surfaces. It remains unclear how endometrial tissue migrates into the thoracic cavity and produces pneumothorax. Currently proposed hypotheses include retrograde menstruation through diaphragmatic fenestrations, coelomic metaplasia, prostaglandin, hematogenous or lymphatic metastases. None of the theories proposed alone can elucidate all clinical manifestations of this condition, so the etiology of the development of thoracic endometriosis is likely to be multifactorial and closely intertwined with each other hypothesis.

Introduction

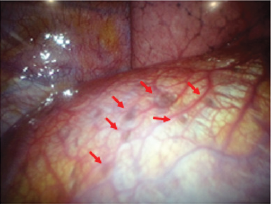

Endometriosis is a condition in which endometrial-like glands and stroma are located outside of the uterine cavity. The ectopic endometrium is encountered most commonly pelvic structures such as ovary, uterine ligaments, pelvic peritoneum, and genital structures [1-4]. The usual site of endometriosis outside of the abdominopelvic cavity is in or around the lung (intrathoracic cavity) (Figure 1). Although endometriosis in general can affect up to 15% of women of reproductive age, thoracic endometriosis remains a very rare condition [5-9]. Thoracic endometriosis produces a broad range of clinical and radiological manifestations, including catamenial pneumothorax (80%), catamenial hemothorax (15%), hemoptysis (5%), and rarely pulmonary nodules [5-9]. The age of onset in patients with thoracic endometriosis (a mean of 35 years) is higher compared to a mean age at presentation of 25 to 30 years in patients with only pelvic endometriosis [5-9]. The exact mechanism of catamenial pneumothorax associated with thoracic endometriosis remains unclear, but several hypotheses have developed to explain this condition.

Figure 1: Endometriosis involving the pleural surface of diaphragm (arrows). The clinical and laboratory findings have been reported previously [32].

Retrograde Menstruation through Diaphragmatic Fenestrations

The endometrial tissue is thought to move through the fallopian tubes to the peritoneal cavity by retrograde menstruation backflow [4]. The endometrial cells in peritoneal fluid may follow clockwise peritoneal circulation and pass through the right paracolic gutter towards the right sub-diaphragmatic region. The phrenicocolic ligament on the left side and falciform ligament form barriers that prevent cells and fluids from reaching the left sub-diaphragmatic area [10,11]. Implantation of endometrial cell leads to the formation of endometriotic nodules on the ventral side of the diaphragm [10]. The nodules cause cyclical necrosis and induce diaphragmatic fragility, leading to the formation of the usual diaphragmatic fenestrations. After endometrial tissue enters the pleural space, it may form colonies in other part of the diaphragm or in the pleural space. Air leaks from vagina may occur during the menstrual cycle when the cervical mucus plug is deleted [10-14]. This hypothesis may be in good agreement with the observation that endometriosis occurs nine times frequently on the right hemidiaphragm than on the left [4,6,14,15].

Coelomic Metaplasia

The second proposes the coelomic metaplasia mechanism that causes endometriosis by metaplasia of mesothelial cells lining the pleura and peritoneal surfaces into endometrial stroma and gland [9,16,17]. Transformation of these cells may be affected by physiological stimuli such as estrogen [18]. Support for this hypothesis is observed in endometriosis patients with Mayer- Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome who lack a functional endometrium [19,20]. Rare cases of endometriosis can also occur in men receiving high-dose estrogen. The coelomic metaplasia hypothesis provides an explanation for pleural cases of thoracic endometriosis. However, this fails to explain the right-sided predominance seen in patients with thoracic endometriosis.

Prostaglandin

The third is a bioactive substance-mediated mechanism in which high levels of prostaglandins, in particular prostaglandin F2α. Prostaglandins are detectable in the plasma of women during menstruation. Circulating prostaglandins increase with menstruation [21,22-25] and causes vascular and bronchiolar vasoconstriction, leading to the vasospasm and associated ischemia within the lung [23,25,26]. This may result in alveolar rupture of previously formed subpleural blebs and bullae, and subsequent air leaks [23,25-27].

Hematogenous or Lymphatic Metastasis

An interesting hypothesis of metastasis suggests that endometrial transplantation occurs through lymphatic or hematogenous dissemination of endometrial cells, explaining both the thoracic and other sites of implantation, in an analogous manner to cancer metastasis [7,28,29]. Review of autopsy data of humans with thoracic endometriosis shows that patients with bronchopulmonary endometriosis usually have bilateral lesions, whereas diaphragmatic and pleural diseases are predominantly right sides [17]. Perhaps the most compelling evidence for the benign metastasis hypothesis is derived from the investigations of ectopic endometriosis lesions occurring in remote parts of the body including the bone or brain [8,21,30-32].

Comment

Thoracic endometriosis is characterized by the presence of endometrial-like glands and stroma within the lung parenchyma or on the diaphragm and pleural surfaces. It remains unclear how endometrial tissue migrates to the thoracic cavity, but it is often associated with abdominal endometriosis. As none of the theories proposed alone can account for all clinical manifestations of this condition, so the etiology of thoracic endometriosis development is likely multifactorial and closely intertwined with each other hypothesis.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this report.

References

- Agarwal N, Subramanian A (2010) Endometriosis - morphology, clinical presentations and molecular pathology. J Lab Physicians 2(1): 1-9.

- Giudice LC (2010) Clinical practice Endometriosis. N Engl J Med 362(25): 2389-2398.

- Veeraswamy A, Lewis M, Mann A, Kotikela S, Hajhosseini B, et al. (2010) Extragenital endometriosis. Clin Obstet Gynecol 53(2): 449-466.

- Vinatier D, Orazi G, Cosson M, Dufour P (2001) Theories of endometriosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 96(1): 21-34.

- Azizazad-Pinto P, Clarke D (2014) Thoracic endometriosis syndrome: case report and review of the literature. Perm J 18(3): 61-65.

- Joseph J, Sahn SA (1996) Thoracic endometriosis syndrome: New observations from an analysis of 110 cases. Am J Med 100(2): 164-170.

- Javert CT (1951) Observations on the pathology and spread of endometriosis based on the theory of benign metastasis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 62(3): 477-487.

- Huang H, Li C, Zarogoulidis P, Darwiche K, Machairiotis N, et al. (2013) Endometriosis of the lung: report of a case and literature review. Eur J Med Res 18(1): 13.

- Alifano M, Roth T, Broet SC, Schussler O, Magdeleinat P, et al. (2003) Catamenial pneumothorax: a prospective study. Chest 124(3): 1004-1008.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C (2012) Endometriosis: Ancient disease, ancient treatments. Fertil Steril 98(6 Suppl): S1-S62.

- Kirschner PA (1998) Porous diaphragm syndromes. Chest Surg Clin N Am 8(2): 449-472.

- Alifano M, Cancellieri A, Fornelli A, Trisolini R, Boaron M (2004) Endometriosis-related pneumothorax: Clinicopathologic observations from a newly diagnosed case. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 127(4): 1219-1221.

- Maurer ER, Schaal JA, Menden FL Jr (1958) Chronic recurring spontaneous pneumothorax due to endometriosis of the diaphragm. J Am Med Assoc 168(15): 2013-2014.

- Papafragaki D, Concannon L (2008) Catamenial pneumothorax: a case report and review of the literature. J Womens Health 17(3): 367-372.

- Channabasavaiah AD, Joseph JV (2010) Thoracic endometriosis: revisiting the association between clinical presentation and thoracic pathology based on thoracoscopic findings in 110 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 89(3): 183-188.

- Nezhat C, Lindheim SR, Backhus L, Vu M, Vang N, et al. (2019) Thoracic endometriosis syndrome: a review of diagnosis and management. JSLS 23(3): e2019.00029.

- Kovarik JL, Toll GD (1966) Thoracic endometriosis with recurrent spontaneous pneumothorax. JAMA 196(6): 595-597.

- Matsuura K, Ohtake H, Katabuchi H, Okamura H (1999) Coelomic metaplasia theory of endometriosis: evidence from in vivo studies and an in vitro experimental model. Gynecol Obstet Invest 47(Suppl 1): 18-20.

- Mok-Lin EY, Wolfberg A, Hollinquist H, Laufer MR (2010) Endometriosis in a patient with Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome and complete uterine agenesis: evidence to support the theory of coelomic metaplasia. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 23(1): e35-e37.

- Schrodt GR, Alcorn MO, Ibanez J (1980) Endometriosis of the male urinary system: a case report. J Urol 124(5): 722-723.

- Korom S, Canyurt H, Missbach A, Schneiter D, Kurrer MO, et al. (2004) Catamenial pneumothorax revisited: Clinical approach and systematic review of the literature. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 128(4): 502-508.

- Shiraishi T (1991) Catamenial pneumothorax: report of a case and review of the Japanese and non-Japanese literature. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 39(5): 304-307.

- Bagan P, Le Pimpec Barthes F, Assouad J, Souilamas R, Riquet M (2003) Catamenial pneumothorax: retrospective study of surgical treatment. Ann Thorac Surg 75(2): 378-381.

- Shearin RP, Hepper NG, Payne WS (1974) Recurrent spontaneous pneumothorax concurrent with menses. Mayo Clin Proc 49(2): 98-101.

- Rossi NP, Goplerud CP (1974) Recurrent catamenial pneumothorax. Arch Surg 109(2): 173-176.

- Joseph J, Reed CE, Sahn SA (1994) Thoracic endometriosis. Recurrence following hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and successful treatment with talc pleurodesis. Chest 106(6): 1894-1896.

- Cowl CT, Dunn WF, Deschamps C (1999) Visualization of diaphragmatic fenestration associated with catamenial pneumothorax. Ann Thorac Surg 68(4): 1413-1414.

- Ueki M (1991) Histologic study of endometriosis and examination of lymphatic drainage in and from the uterus. Am J Obstet Gynecol 165(1): 201-209.

- Alifano M, Trisolini R, Cancellieri A, Regnard JF (2006) Thoracic endometriosis: current knowledge. Ann Thorac Surg 81(2): 761-769.

- Sampson J (1921) Perforating hemorrhagic (chocolate) cysts of the ovary. Their importance and especially their relationship to pelvic adenoma of endometrial type (“adenomyoma” of the uterus, rectovaginal septum, sigmoid, etc). Arch Surg 3(2): 245-323.

- Gates J, Sharma A, Kumar A (2018) Rare case of thoracic endometriosis presenting with lung nodules and pneumothorax. BMJ Case Rep.

- Imai A, Ichigo S, Takagi, H, Matsunami K, Nishimura N, et al. (2020) Pneumothorax found during health check-up as a manifestation of thoracic endometriosis. Biomed J Sci Tech Res.

Mini Review

Mini Review