Abstract

Mosquitoes play an important role in transmitting a wide range of viral and parasitic diseases to humans and animals. Due to the importance of mosquitoes in human and animal health, the present study was performed to evaluate diseases transmitted by mosquitoes and the status of these diseases in Kashan County. We searched the main databases such as Web of Science, PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, Scientific Information Database (SID), Iran Medex, and Magiran about the mosquito-borne diseases of Iran and Kashan County up to May 2021. Also, the checklist of mosquitoes of Kashan County was prepared. There is no published information about mosquito-borne diseases in livestock and animals in Kashan. Human malaria is the only mosquito-borne disease reported in Kashan County. From 2005 to 2016 all human malaria cases in this county were only reported from Afghan immigrants and from 2017 to 2020 no human malaria case has been not reported in Kashan County. Lumpy skin disease is a vector-borne pox disease of domestic cattle that has been reported from 31 provinces in Iran. This disease has not been observed in Kashan so far, but due to the presence of the disease in livestock of neighboring provinces, there is a risk of disease for Kashan. Information about the role of mosquitoes in the transmission of pathogens in Kashan County is limited. Due to the importance of mosquito-borne diseases, mosquito surveillance is necessary for the best-integrated vector management.

Keywords: Mosquito-Borne Disease; Lumpy Skin Disease; Human; Avian Malaria

Introduction

More than 17% of infectious diseases are vector-borne diseases that cause 700,000 deaths annually [1]. About 60% of emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases are zoonoses. In the last three decades, more than 30 new human pathogens have been identified, 75% of which are of animal origin [2]. In the Eastern Mediterranean Region of WHO, zoonoses are a public health threat [3]. Mosquitoes are considered the most important arthropods in medicine and health due to the transmission of pathogens causing some important infectious diseases such as malaria, filariasis, and arboviral diseases [4-6] and are present worldwide except Antarctica [7]. Mosquitoes belong to the order Diptera, suborder Nematocera, and family Culicidae [8]. Culicidae has two subfamilies Anophelinae and Culicinae and 70 species in Iran. Mansonia uniformis was the newest genus and species that was added to the mosquito fauna in Iran [9]. Mosquito larvae are found in a variety of environments, including natural and man-made habitats, with temporary or permanent water sources, stagnant or running water, contaminated or clean water, with or without vegetation. Mosquito larvae are also found in small places where water collects, such as pots, used tires, and animal footprints [4,5]. According to the latest study conducted of mosquito fauna in Kashan, there are 3 genera and 13 species in this county including Anopheles. claviger, An. maculipennis s.l., An. superpictus s.l., An. turkhudi, Culex deserticola, Cx. hortensis, Cx. mimeticus, Cx. perexiguus, Cx. pipiens, Cx. theileri, Culiseta annulata, Cs. longiareolata, Cs. subochrea [10], also Cx. torrentium larva has been found at an ovitrap in Kashan County [11], and species of Anopheles multicolor, Culex modestus, Aedes caspius, and Ae. pulcritarsis have been reported from previous studies in this county [12,13]. Susceptibility to mosquito-borne diseases has increased due to globalization and led to the spread of emerging and re-emerging pathogens in new and old habitats. Economic and social factors, global trade, transport and tourism have caused the spread of vectors and diseases transmitted by them [7,14]. In livestock, mosquito bites may cause stress and pain, resulting in reduced livestock fitness. In addition, mosquitoes can also transmit pathogen between livestock reservoirs (episodic) and, humans (zoonotic diseases) [7]. Mosquitoes can transmit pathogens in Iran, including causes of arboviral diseases (avian pox, bovine ephemeral fever, dengue fever, Rift Valley fever, West Nile fever), bacterial diseases (Anthrax, Tularemia), helminthic diseases or helminthiases (mosquito-borne filariasis), protozoans (Avian malaria, Human malaria) [6]. Due to global climate change, more animal and human populations will be exposed to these pathogens [7]. Due to the importance of mosquitoes in human and animal health, the present study was performed to evaluate diseases transmitted by mosquitoes and the status of these diseases in Kashan County

Mosquito- Borne Diseases in Kashan County

To find diseases transmitted by mosquitoes, we searched the terms “mosquito-borne pathogens”, “mosquito-borne diseases”, “mosquito-borne infections”, “mosquito-borne viruses”. Data were extracted from all articles. An intensive search of scientific literature was reviewed using the search term in the following databases: “PubMed”, “Web of Knowledge”, “Scopus”, “Google Scholar”, “SID”, etc. Mosquito-borne disease names including ‘malaria, avian malaria, West Nile (WN) fever, Dengue (DEN) fever, Sindbis (SIN) fever, lymphatic filariasis, tularemia, tularaemia, anthrax’, lumpy skin, and mosquito-borne pathogens such as Plasmodium, Dirofilaria, Flavivirus, Alphavirus, Phlebovirus, Orthobunyavirus were reviewed. Also, cases of mosquito-borne diseases identified in Kashan, were inquired from Kashan University of Medical Sciences and Kashan Veterinary Organization.

Protozoal Diseases

Human Malaria

Malaria is a health threat. This disease is caused by a parasite

that is transmitted to humans through the bite of infected Anopheles

mosquitoes and can be prevented and treated. In 2019, almost

half of the world’s population was at risk for malaria. Most deaths

occur in sub-Saharan Africa. However, Southeast Asia, Eastern

Mediterranean, Western Pacific, and Americas also have the case of

diseases and deaths. In 2019, cases and the number of deaths due

to malaria were 229 million and 409,000, respectively. Plasmodium

falciparum and Plasmodium vivax are the most important

parasite species of human malaria [15,16], which are biologically

transmitted by some anopheline mosquitoes [17]. Many effective

efforts have been done for malaria control in the past that caused

decreased morbidity and mortality in Iran [18,19]. At the present,

malaria has been eliminated in most parts of Iran [20]. A malaria

pre-elimination program started in Iran in 2009, restricted the local

transmission of this disease [21]. The results of a study showed

that the imported cases (from the eastern neighboring countries)

have increased from 2009 onward, compared to indigenous cases

[20]. WHO (2020) reported the Islamic Republic of Iran had no

indigenous malaria cases in 2018 and 2019[15].

Kashan County is located in the central plateau region of Iran,

where have a lower risk of malaria infection compared to southern/

southeastern parts. Seven Anopheles species (An. maculipennis

Meigen s.l., An. sacharovi Favre, An. culicifacies Giles s.l., An. dthali

Patton, An. fluviatilis James s.l., An. stephensi Liston, An. superpictus

Grassi s.l.) are malaria vectors in Iran [22]. Anopheles superpictus

s.l. species is the most abundant and distributed among Anopheles

in Kashan County [10,12,13], and is one of the seven species of

malaria vectors in Iran [22,23], also An. maculipennis s.l. [10,12],

An. claviger [10,12,13], An. multicolor [12,13], and An. turkhudi

[10] have been reported from Kashan County. An. maculipennis s.l.

is the main vector in the Caspian coast in northern Iran [24]. In

Kashan County, from 1986 to 1997, a total of 498 malaria patients

have been reported, of which 95% were Afghan immigrants and

5% were Iranian travelers or immigrants from other parts of the

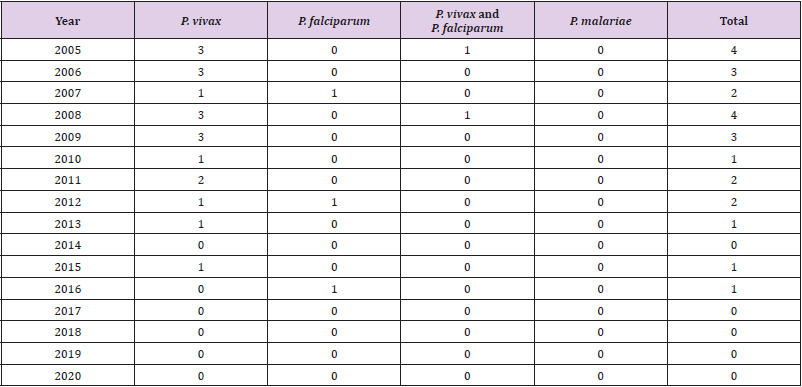

country [13]. There are malaria cases from 2005 to 2020 and

parasite species in Table 1, all malaria cases in these years were

reported from Afghan immigrants.

Avian Malaria (Bird Malaria)

Culicidae mosquitoes belonging to different genera (Culex, Coquillettidia, Aedes, Mansonia, Culisetta, Anopheles, Psorophora) transmit many species of avian Plasmodium [25-29]. Bird malaria has been reported in some provinces of Iran including Fars Province [30,31], and Mazandaran Province [32,33]. Kalani et al. for the first time, reported two hematozoa, including Aegyptianella and Plasmodium in Isfahan Province [34]. But no information is available about the vectors of this disease in birds in these provinces. Culex pipiens is the main vector in some countries including Austria [35], Japan [28], Portugal [36], Spain [37], and Turkey [38]. In Austria Cx. torrentium is also main vector [35]. Culex theileri in Portugal and Spain are known as a vector [36,37]. Aedes caspius s.l., Cx. modestus and Cx. perexiguus are vectors in Spain [37]. No avian malaria has been reported from birds in Kashan County, but there are species of Aedes caspius s.l, Cx. pipiens, Cx. torrentium, Cx. theileri, Cx. modestus and Cx. perexiguus in different districts of the county [10-12].

Mosquito-Borne Viruses (Arboviral Diseases)

Bovine Ephemeral Fever

Bovine ephemeral fever is an arthropod-borne disease of cattle and water buffaloes. The disease agent is from the genus Ephemerovirus within the Rhabdoviridae family. Biting midges (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae) and mosquitoes Aedes, Anopheles and Culex are known as the main vectors [39-42]. There is no information about the vectors of the virus in Iran [6]. In Iran, bovine ephemeral fever virus has been found in cattle and water buffalo in provinces Razavi Khorasan [43], Khuzistan [44], Fars, Tehran, West Azerbaijan [45], and Qazvin [46]. The virus has not been reported in Kashan County.

West Nile Fever

West Nile Virus (WNV) distributed in Africa, Europe, the Middle East, North America, and West Asia, is a member of the family Flaviviridae, Flavivirus genus, and belongs to the Japanese encephalitis complex. Human is most often infected by infected mosquito bites. Genus Culex is the principal vector of WNV, in particular Cx. pipiens. Birds are the reservoir hosts of WNV, In Europe, Africa, Middle East, and Asia [1,47]. In nature WNV is held in a mosquito-bird-mosquito transmission cycle and Culex spp. are the main vectors [48]. In a study, Cx. pipiens infection with WNV was reported in Guilan Province, north of Iran [49]. Also, it has been reported that Aedes caspius to be infected with the virus in the northwest of Iran [50]. West Nile virus has been identified by ELISA in horses in at least 26 of the 31 Iranian provinces and is the most important and most widespread mosquito-borne arbovirus in Iran [51-53]. Culex perexiguus, and Cx. modestus have also been reported as the principal vectors of WNV in Asia and Europe [54]. These mosquitoes have been reported from Kashan County [10,12], but no information is available about them, and birds infected with WNV in this County.

Lumpy Skin Disease (LSD)

Lumpy skin disease is a vector-borne pox disease of domestic cattle and Asian water buffalo and is characterized by the appearance of skin nodules [55]. Lumpy skin disease virus (LSDV) is a member of the genus Capripoxvirus and the family Poxviridae and is one of the most warning diseases in cattle from the perspective of OIE (Organization for World Health Animal Diseases), so it is mandatory that disease-free countries report it to OIE within 24 hours of confirmation of the disease [56]. The original vector is probably different in geographical areas, including the common stable fly (Stomoxys calcitrans), mosquitoes such as Aedes aegypti, and some species of African mites Rhipicephalus and Amblyomma spp. [55]. Lumpy skin disease (LSD) outbreaks in Kenya were caused incidence of Aedes natronius and Culex mirificus mosquitoes [57]. Culex spp. mosquitoes that feed multiple times on different hosts can increase the probability of transmission [58]. Lumpy skin disease was first seen in Zambia in 1929, then spread to all parts of the Sub-Saharan Africa as well as Madagascar. This disease was first observed in 2014 in western Iran. The outbreak of the disease in Iran followed the spread of the disease in neighboring western countries, including Turkey and Iraq. This disease has been reported from 31 provinces of the country with different prevalence percentages and epidemiological data of the disease indicate that the disease has spread epidemically among cattle and calves of different breeds. High risk provinces were including the provinces of West Azerbaijan, Kurdistan, Ilam, Khuzestan, and Kermanshah. Epidemiological data of the disease in the country show that the prevalence is less than 1% (0.55%) [59]. This disease has not been observed in Kashan so far, but due to the presence of the disease in livestock of neighboring provinces, there is a risk of disease for Kashan.

Mosquito-Borne Filariases

Dirofilariasis

Dirofilaria is a long, slender parasitic worm that infects a variety of mammals. The infection is transmitted by mosquito bites. There are many species of Dirofilaria, but infection in humans is usually caused by three species: D. immitis, D. repens, and D. tenuis. Dogs and wild dogs such as foxes and wolves are the main natural hosts of these three species. Dirofilaria immitis is also known as “heart worm” [60]. Dirofilaria repens and D. immitis infection has been found in humans and dogs in 16 provinces of Iran including Guilan [61], Garmsar [62], East Azarbijan Province [63], Gilan, Mazandaran, Golestan, East, and West Azerbaijan, Ardebil, Markazi, Isfahan, Khorassan, Khuzestan and Hormozgan [64,65], Ahvaz City [66,67], Kerman [68], and Meshkin-Shahr [69]. Vector of D. immitis in Ardebil Province is Cx. theileri [61,70]. There is no information about this disease in Kashan County.

Setariasis (Setariosis)

Setaria (Nematoda: Spirurida: Onchocercidae: Setariinae) infects ruminants. Species of Setaria digitata, S. equina, S. labiatopapillosa, S. marshali, S. cervi have been reported in horses, cattle, sheep, goats, donkeys, wild sheep, and water buffalo in 10 provinces [71-82]. This nematod is transmitted by mosquito species of the genera Aedes, Anopheles, Armigeres Theobald, Culex and Mansonia [83]. Setaria equine has been found from Anopheles maculipennis females in Ardebil Province [70]. There is no information about this disease in Kashan County.

Checklist of Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) of Kashan County

A checklist of mosquitoes of Kashan County is presented as

follow:

Family Culicidae Meigen, 1818

Subfamily Anophelinae Grassi, 1900

Genus Anopheles Meigen, 1818

Subgenus Anopheles Meigen, 1818

1. An. (Ano.) claviger (Meigen, 1804)

2. An. (Ano.) maculipennis s. l. Meigen, 1818

Subgenus Cellia Theobald, 1902

1. An. (Cel.) superpictus s. l. Grassi, 1899

2. An. (Cel.) multicolor Combouliu, 1902

3. An. (Cel.) turkhudi Liston, 1901

Subfamily Culicinae Meigen, 1818

Tribe Aedini Neveu-Lemaire, 1902

Genus Aedes Meigen, 1818

Subgenus Ochlerotatus Lynch Arribálzaga, 1891

1. Ae. (Och.) caspius (Pallas, 1771) s.l. [Oc. caspius (Pallas) s.l.]

2. Ae. (Och.) pulcritarsis (Rondani, 1872) [Oc. pulcritarsis

(Rondani)]

Tribe Culicini Meigen, 1818

Genus Culex Linneaus, 1758

Subgenus Barraudius Edwards, 1921

1. Cx. (Bar.) modestus Ficalbi, 1889

Subgenus Culex Linneaus, 1758

1. Cx. (Cux.) pipiens Linnaeus, 1758 (see Note 26)

2. Cx. (Cux.) torrentium Martini, 1925

3. Cx. (Cux.) perexiguus Theobald, 1903

4. Cx. (Cux.) theileri Theobald, 1903

5. Cx. (Cux.) mimeticus Noè, 1899

Subgenus Maillotia Theoald, 1907

1. Cx. (Mai.) deserticola Kirkpatrick, 1924

2. Cx. (Mai.) hortensis Ficalbi, 1889

Tribe Culisetini Belkin, 1962

Genus Culiseta Felt, 1904

Subgenus Allotheobaldia Broelemann, 1919

1. Cs. (All.) longiareolata (Macquart, 1838)

Subgenus Culiseta Felt, 1904

1. Cs. (Cus.) annulata (Schrank, 1776)

2. Cs. (Cus.) subochrea (Edwards, 1921)

Conclusion

Information about the role of mosquitoes in the transmission of pathogens in Kashan County is limited. Due to the construction of bird garden in Qamsar, and entry of birds from 17 different countries into this area, and importance of mosquito-borne diseases in the country, vector-borne disease surveillance, is necessary for the best integrated vector management. The life cycle of mosquitoes requires two types of environments: aquatic habitats (eggs, larvae, and pupae) and terrestrial ecosystems (adults) [17]. Control strategies of mosquitoes may be to controlling adults or larvae at the breeding sites. Methods of insecticide-treated bed nets (ITN) and indoors residual spraying (IRS) are used to control adult mosquitoes [84]. But these methods are not effective in controlling exophilic and exophagic mosquitoes [85]. Environmental management is one of the most effective and sustainable methods for controlling of vectors of diseases. The concept of environmental management for mosquito control is a range of methods including long-lasting physical transformation of larval habitats, temporary changes of larval habitats, which makes the environmental conditions unsuitable for vector breeding, and reduce human/vector/ pathogen contact [86]. Application of these methods depending on the type of larval habitat can reduce mosquito populations and reduce the risk of disease transmission.

Acknowledgement

Authors are grateful to Kashan Veterinary Organization and Health Deputy, Kashan University of Medical Sciences, for Cooperation.

Funding

This work was supported by No.: IR.TUMS.VCR.REC.1397.1001.

Availability of Data and Materials

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Author’s Contributions

Seyed Hassan Moosa-Kazemi (SHM) and Mohammad Mehdi Sedaghat (MMS) designed and organized the work. Tahereh Sadat Asgarian (TSA) performed the literature search and wrote the manuscript. Mohsen Akbarian (MA) provided information about malaria. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- (2017) WHO. West Nile virus.

- Jones KE, Patel NG, Levy MA, Storeygard A, Balk D, et al. (2008) Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature 451: 990-993.

- Malik MR, El Bushra HE, Opoka M, Formenty P, Velayudhan R, et al. (2013) Strategic approach to control of viral haemorrhagic fever outbreaks in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: report from a regional consultation. East Mediterr Health J 19(10): 892-897.

- Zaim M, Manouchehri A, Yaghoobi-Ershadi MM (1984) Investigation of fauna of mosquitoes of Iran (Diptera: Culicidae) 1- Aedes. Iran J Health Sci 13: 3-10.

- Zaim M (1987) Malaria control in Iran. J Am Mosq Control Assoc 3: 392-396.

- Azari-Hamidian S, Norouzi B, Harbach RE (2019) A detailed review of the mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) of Iran and their medical and veterinary importance. Acta Trop 194: 106-122.

- Garros C, Bouyer J, Takken W, Smallegange RC (2018) Control of vector-borne diseases in the livestock industry: new opportunities and challenges. In Pests and vector-borne diseases in the livestock industry. Wageningen Academic Publishers, pp: 337-387.

- Gaffigan TV, Wilkerson RC, Pecor JE, Stoffer JA, Anderson T (2018) Systematic Catalog of Culicidae. Walter Reed Biosystematic Unit, Smithsonian Institution.

- Azari-Hamidian S, Abaei MR, Nourouzi B (2020) Mansonia uniformis (Diptera: Culicidae), a genus and species new to southwestern Asia, with a review of its medical and veterinary importance. Zootaxa 4772: 385-395.

- Asgarian TS, Moosa-Kazemi SH, Sedaghat MM, Dehghani R, Yaghoobi-Ershadi MR (2021) Fauna and larval habitat characteristics of mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in Kashan County. Central Iran J Arthropod Borne Dis 15(1): 69-81.

- Asgarian TS (2020) Investigation of the current status of the distribution of Aedes mosquitoes using different collection methods in some areas of Kashan County. [MSc thesis]. School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Iran.

- Zaim M (1987) The mosquito fauna of Kashan, public health importance and control. Desert, Scientific Research 18: 1-41.

- Doroudgar A, Dehghani R, Hooshyar H, Sayyah M (2000) Epidemiology of malaria in Kashan. Med Fac Guilan Univ Med Sci 8: 52-58.

- Schaffne F, Versteirt V, Medlock J (2014) Guidelines for the surveillance of native mosquitoes in Europe: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC).

- (2020) WHO. World malaria report 2020: 20 years of global progress and challenges. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- (2021) WHO. WHO Guidelines for malaria?

- Becker N, Petrić D, Zgomba M, Boase C, Madon M, et al. (2010) Mosquitoes and their control (2nd )., Berlin, Germany, Springer.

- Edrissian GH (2006) Malaria in Iran: past and present situation. Iran J Parasitol 1: 1-14.

- Moosa-Kazemi SH, Vatandoost H, Raeisi A, Akbarzadeh K (2007) Deltamethrin impregnated bed nets in a malaria control program in Chabahar, southeast Baluchistan, I.R. Iran. J Arthropod-Borne Dis 1(1): 43-51.

- Vatandoost H, Raeisi A, Saghafipour A, Nikpour F, Nejati J (2019) Malaria situation in Iran: 2002–2017. Malar J 18: 200.

- Kafl SH (2017) Malaria in Iran: is the elimination phase a target? Ann Trop Med Public Health 10: 1062.

- Hanafi-Bojd AA, Azari-Hamidian S, Vatandoost H, Charrahy Z (2011) Spatio-temporal distribution of malaria vectors (Diptera: Culicidae) across different climatic zones of Iran. Asian Pac J Trop Med 4: 498-504.

- Shahgudian ER (1960) A key to the Anophelines of Iran. Acta Medica. Iranica.

- Sedaghat MM, Harbach RE (2005) An annotated checklist of the Anopheles mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in Iran. J Vector Ecol 30: 272-276.

- Garnham PCC (1966) Malaria parasites and other Haemosporidia. Blackwell, Oxford, England; Davis, Philadelphia.

- Valkiunas G (2004) Avian malaria parasites and other haemosporidia. CRC press.

- Njabo KY, Cornel AJ, Sehgal RN, Loiseau C, Buermann W, et al. (2009) Coquillettidia (Culicidae, Diptera) mosquitoes are natural vectors of avian malaria in Africa. Malar J 8: 193.

- Ejiri H, Sato Y, Kim KS, Tsuda Y, Murata K, et al. (2011) Blood meal identification and prevalence of avian malaria parasite in mosquitoes collected at Kushiro Wetland, a subarctic zone of Japan. J Med Entomol 48: 904-908.

- Santiago‐Alarcon D, Palinauskas V, Schaefer HM (2012) Diptera vectors of avian Haemosporidian parasites: untangling parasite life cycles and their taxonomy. Biol Reviews 87: 928-964.

- Nazifi S, Razavi SM, Yavari F, Rajaifar M, Bazyar E, et al. (2008) Evaluation of hematological values in indigenous chickens infected with Plasmodium gallinaceum and Aegytianella pullorum. Comp Clin Pathol 17: 145-148.

- Mohaghegh MA, Namdar F, Azami M, Ghomashlooyan M, Kalani H, et al. (2018) The first report of blood parasites in the birds in Fasa district, Southern Iran. Comp Clin Path 27: 289-293.

- Faghihzadeh Gorji S, Shemshadi B, Habibi H, Jalali S, Davary M, et al. (2012) Survey on parasites in sparrows of Amol (Mazandaran Province, Iran). J Life Sci 6: 783-785.

- Fakhar M, Kalani H, Rahimi-Esboei B, Armat S (2013) Hemoprotozoa in free-ranging birds from rural areas of Mazandaran Province, northern Iran. Comp Clin Pathol 22: 509-512.

- Kalani H, Faridnia R, Pestechian N, Cheraghipor K (2015) The first report of hematozoain migratory and native birds in Isfahan Province, Iran. Comp Clin Pathol 24: 65-68.

- Schoener E, Uebleis SS, Butter J, Nawratil M, Cuk C, et al. (2017) Avian Plasmodium in Eastern Austrian mosquitoes. Malar J 16: 389.

- Ventim R, Ramos JA, Osório H, Lopes RJ, Pérez-Tris J, et al. (2012) Avian malaria infections in western European mosquitoes. Parasitol Res 111: 637-645.

- Ferraguti M, Martınez-de la Puente J, Munoz J, Roiz D, Ruiz S, Soriguer R, et al. (2013) Avian Plasmodium in Culex and Ochlerotatus mosquitoes from southern Spain: effects of season and host-feeding source on parasite dynamics. PLOS One 8: 6.

- Inci A, Yildirima A, Njabob KY, Duzlua O, Biskina Z, et al. (2012) Detection and molecular characterization of avian Plasmodium from mosquitoes in central Turkey. Vet Parasitol 188: 179-184.

- Nandi S, Negi BS (1999) Bovine ephemeral fever: a review. Com Immun Mircob Infect Dis 22: 81-91.

- Mellor PS (2001) Bovine ephemeral fever. In: Service MW (Edt.)., Encyclopedia of arthropod-transmitted infections of man and domesticated animals. CABI Publishing, Wallingford, pp: 87-91.

- Yeruham I, Gur Y, Braverman Y (2007) Retropective epidemiological investigation of an outbreak of bovine ephemeral fever in 1991 affecting dairy cattle herds on the Mediterranean coastal plain. Vet J 173: 190-193.

- Walker PJ, Klement E (2015) Epidemiology and control of bovine ephemeral fever. Vet Res 46: 124.

- Hazrati A, Hessami M, Roustai M, Dayhim F (1975) Isolation of bovine ephemeral fever virus in Iran. Arch Razi Inst 27: 80-81.

- Momtaz H, Nejat S, Moazeni M, Riahi M (2012) Molecular epidemiology of bovine ephemeral fever virus in cattle and buffaloes in Iran. Revue Med Vet 163: 415-418.

- Bakhshesh M, Abdollahi D (2015) Bovine ephemeral fever in Iran: diagnosis, isolation and molecular characterization. J Arthropod-Borne Dis 9(2): 195-203.

- Mirzaei K, Bahonar A, Fallah Mehrabadi M, Hajilu G, Yaghoubi M (2017) Determinants of bovine ephemeral fever outbreak during 2013, in Qazvin Province, Iran. Asian Pac J Trop Dis 7: 744-747.

- (2013) CDC. West Nile virus in the United States: Guidelines for surveillance, prevention, and control.

- Turell MJ, Sardelis MR, Dohm DJ, O'Guinn ML (2001) Potential North American vectors of West Nile virus. Ann N Y Acad Sci 95: 317-324.

- Shahhosseini N, Chinikar S, Moosa-Kazemi SH, Sedaghat MM, Kayedi MH, et al. (2017) West Nile virus lineage-2 in Culex speciments from Iran. Trop Med Int Health 22: 1343-1349.

- Bagheri M, Terenius O, Oshaghi MA, Motazakker M, Asgari S, et al. (2015) West nile virus in mosquitoes of iranian wetlands. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 15(12).

- Ahmadnejad F, Otarod V, Fallah MH, Lowenski S, Sedighi-Moghaddam R, et al. (2011) Spread of West Nile virus in Iran: a cross-sectional serosurvey in equines, 2008–2009. Cambridge University Press 139: 1587-1593.

- Chinikar S, Shah-Hosseini N, Mostafavi E, Moradi M, Khakifirouz S, et al. (2013) Seroprevalence of west nile virus in iran. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 13: 586-589.

- Pourmahdi Borujeni M, Ghadrdan Mashadi A, Seifi Abad Shapouri M, Zeinvand M (2013) Aserological survey on antibodies against West Nile virus in horses of Khuzestan Province. Iran J Vet Med 7: 185-191.

- Hubálek Z, Halouzka J (1999) West Nile fever-a reemerging mosquito-borne viral disease in Europe. Emerg Infect Dis 5: 643-650.

- Tuppurainen E, Alexandrov T, Beltrán-Alcrudo D (2017) Lumpy skin disease field manual – A manual for veterinarians. FAO Animal Production and Health Manual No. 20. Rome. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), p. 60.

- (2016) OIE. Lumpy skin disease. OIE Manual of Diagnostic Tests Vaccines Terr. Animals, p. 1-14.

- Burdin ML, Prydie J (1959) Observations on the first outbreak of lumpy skin disease in Kenya. Bull Epizoot Dis Africa 7: 21-26.

- Sprygin A, Pestova Y, Wallace DB, Tuppurainen E, Kononov AV (2019) Transmission of lumpy skin disease virus: A short review. Virus Res 1: 197637.

- Amiri K, Bahreinipour A (2019) Program and executive instructions, Health and management of animal diseases.

- (2020) CDC. Dirofilariasis.

- Azari-Hamidian S, Yaghoobi-Ershadi MR, Javadian E, Mobedi I, Abai MR (2007) Review of dirofilariasis in Iran. J Med Fac Guilan Univ Med Sci 15: 102-113.

- Ranjbar-Bahadori S, Hekmatkhah A (2007) A study on filariosis of stray dogs in Garmsar. J Vet Res 62: 73-76.

- Razmaraii N, Ameghi Roodsary A, Karimi GR, Ebrahimi M (2008) Dirofilaria immitis in wild carnivores in East Azarbijan Province in Iran. Pajouhsh Sazandegi 79: 23-26.

- Meshgi B, Eslami A, Bahonar AR, Kharrazian-Moghadam M, Gerami-Sadeghian A (2009) Prevalence of parasitic infections in the red fox (Vulpes vulpes) and golden jackal (Canis aureus) in Iran. Iran J Vet Res 10: 387-391.

- Javadi S, Hanifeh M, Tavassoli M, Dalir-Naghadeh B, Khezri A, et al. (2011) Dirofilariasis in shepherd dogs of high altitudes areas in West Azerbaijan-Iran. Vet Res Forum 2: 53-57.

- Alborzi A, Mosallanejad B, Ghorbanpoor Najafabadi M, Nikpoor Z (2010) Infestation of heartworm (Dirofilaria immitis) in a cat in Ahvaz City: a case report. J Vet Res 65: 255-257.

- Razi Jalali MH, Alborzi AR, Avizeh R, Mosallanejad B (2010) A study on Dirofilaria immitis in healthy urban dogs from Ahvaz, Iran. Iran J Vet Res 11: 357-362.

- Akhtardanesh B, Radfar MH, Voosoogh D, Darijani N (2011) Seroprevalence of canine heartworm disease in Kerman, southeastern Iran. Comp Clin Pathol 20: 573-577.

- Zarei Z, Kia EB, Heidari Z, Mikaeili F, Mohebali M, et al. (2016) Age and sex distribution of Dirofilaria immitis among dogs in Meshkin-Shahr, northwest Iran and molecular analysis of the isolates based on COX1 gene. Vet Res Forum 7: 325.

- Azari‐Hamidian S, Yaghoobi‐Ershadi MR, Javadian E, Abai MR, Mobedi I, et al. (2009) Distribution and ecology of mosquitoes in a focus of dirofilariasis in northwestern Iran, with the first finding of filarial larvae in naturally infected local mosquitoes. Med Vet Entomol 23: 111-121.

- Eslami AH, Fakhrzadegan F (1972) Nematode parasites of the alimentary canal of cattle in Iran. Rev Elev Med Vet Pay 25(4): 527-529.

- Baharsefat M, Amjadi AR, Yamini B, Ahourai P (1973) The first report of lumbar paralysis in sheep due to nematode larvae infestation in Iran. Arch Inst Razi 2: 63-68.

- Eslami A, Meydani M, Maleki S, Zargarzadeh A (1979) Gastrointestinal nematodes of wild sheep (Ovis orientalis) from Iran. J Wildl Dis 15: 263-265.

- Eslami A, Hergelani YZ (1989) Abattoir investigation on helminth infestations of buffaloes in Iran. J Vet Res 44: 25-34.

- Eslami A (1998) Efficacy of Ivermectin against Setaria digitata in cattle. J Vet Parasitol 12: 58-59.

- Bazargani T, Eslami A, Gholami GR, Molai A, Ghafari-Charati J, et al. (2008) Cerebrospinal nematodiasis of cattle, sheep and goats in Iran. Iran J Parasitol 3: 16-20.

- Gharedagi Y, Jodeiri H, Rohani SR (2008) The first report of equine testicular infestation by Setaria equina in Tabriz. J Spe Vet Sci Islam Azad Univ Tabriz 2: 79-82.

- Enami HR (2009) Epidemiological survey on equine filariasis in the Urmia area of Iran. J Anim Vet Adv 8: 295-296.

- Pourali P, Roayaei Ardakani M, Jolodar A, Jalali R (2009) PCR screening of the Wolbachia in some arthropods and nematods in Khuzestan Province. Iran J Vet Res 10: 216-222.

- Davoodi J (2014) Prevalence of setariosis in small and large ruminant in Miyaneh City, northwest of Iran. Sci J Vet Adv 3: 1-5.

- Khedri J, Radfar MH, Borji H, Azizzadeh M (2014) An epidemiological survey of Setaria in the abdominal cavities of Iranian Sistani and Brahman cattle in the [southeastern] of Iran. Iran J Parasitol 9: 249-253.

- Sadeghi Dehkordi Z, Heidari H, Halajian A (2015) Case report of adult Setaria digitata in sheep, Hamedan Province, Iran. Comp Clin Pathol 24: 185-187.

- Anderson RC (2000) Nematod Parasites of Vertebrates. Their Development and Transmission (2nd)., CABI Publishing, Wallingford.

- (2008) WHO. World malaria report 2008. World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland.

- Killeen GF, Fillinger U, Knols BGJ (2002) Advantages of larval control for African malaria vectors: low mobility and behavioural responsiveness of immature mosquito stages allow high effective coverage. Malar J 1: 8.

- (1980) WHO. Expert Committee on Vector Biology and Control & World Health Organization. Environmental management for vector control: fourth report of the WHO Expert Committee on Vector Biology and Control [meeting held in Geneva from 13 to 19 November 1979]. World Health Organization.

Review Article

Review Article