Abstract

The study was conducted to determine the prevalence and burden of gastrointestinal

(GI) parasites in Cow and buffaloes Calves in rural areas of Rawalpindi. Gastrointestinal

(GI) parasitic infection is a serious issue in cattle management. Effects of GI parasites

may vary with age, sex of cattle, nutritional condition, and severity of infection. A total

of 300 calves were used in this investigation (150 of each buffalo and cow). According to

the findings, worm infection was found in 68.67% of buffalo and 51.33% of cow calves.

Nematodes had the highest prevalence, followed by mixed infection and cestodes,

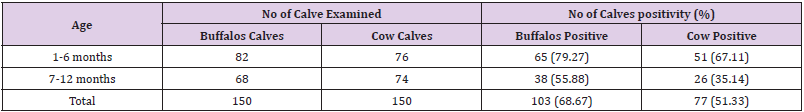

while no calf tested positive for trematodes. Buffalo and cow calves aged 1 to 6 months

had the highest incidence (79.27%, 67.11%) when compared to the age range of 7 to

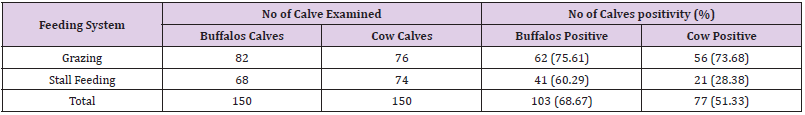

12 months (55.88%, 35.14%). Grazing calves were more infectious (75.61% buffalo

calves, 73.68% cow calves) than stall fed calves (60.29% buffalo calves, 28.38% cow

calves). Male buffalo calves were more afflicted (70.73%) than female buffalo calves

(66.18%), whereas Male cow calves were (55.26%) as compare with female cow calves

(47.30%) affected.

Gastro-intestinal parasitic infection mostly associated with occurrence of diarrhea

in buffaloes, which effect on the health condition and production of these animals,

infections should more attention by both owners and veterinarians. The majority of

farmers in the research region were completely unaware of the recommended calf care

approaches and continued to use traditional methods. Calf mortality was found to be

as high as 60% in the research region, with excessive worm infestation being one of the

main causes, combined with a lack of preventative measures.

Keywords: Prevalence; Endo-Parasites; Cow Calves; Buffalo Calves; Field Conditions

Introduction

Buffaloes are predominantly used for farm power in the

cultivation of rice as well as production of curd [1]. Rearing of

cattle in the country is catering for draught power, milk production,

and meat production [2]. Animals’ gastrointestinal tracts (GIT)

are home to a vast range of parasites, mostly helminthes, which

cause clinical and subclinical parasitism [3]. These parasites

have a negative impact on animal health and result in significant

financial losses for the cattle sector [4]. Parasitic diseases caused

by intestinal parasites constitute a major impediment to livestock

production [5]. All ages of cattle are affected by a diverse set of intestinal parasites. These infections are rarely associated with

high mortality of cattle [6]. However, their effects are usually

characterized by lower outputs of animal products, byproducts,

manure, and traction, thereby affecting the contributions of cattle

in ensuring food security, especially in developing countries [7].

Helminthiosis is a well-recognized problem in free-ranging animals

[8].

One or more helminthes parasites are usually infected cattle,

buffalos, sheep and goats [9]. The differences in the distribution

of parasitic intensity depends upon the topographic, pasturing,

immunological & nutrition of the host, the intermediate host and

number of infective stage or eggs ingested by the animals [10]. In

the development of a profitable livestock industry worm infestation

is one of the major constraints [11]. In the alimentary tract gastrointestinal

helminthiosis syndrome is always caused by a mixture

of species of helminthes parasites [12]. Effect of helminthes on

the production are well documented all over the world [13]. The

reduction in feed intake and anorexia, loss of blood and plasma

proteins in gastro-intestinal tract, alterations in protein metabolism,

decrease in levels of minerals, enzymes and diarrhea, all contribute

to loss in weight gain [14]. Parasitic infection is common in Pakistan

[15], costing the cattle business roughly 26.5 million rupees each

year [16]. Gastrointestinal parasites in calves cause lower growth

and are a persistent hindrance to the development of Pakistan’s

livestock economy [17].

Facing water buffalo herding many obstacles of facing

the economic side for educators such as by internal parasites

in addition to hit the same species that infect cows such as

(Eimeriaspp ,Cryptosporidum spp ,Toxocaravitulorum, Fasciola

spp and Trichostrongylidae) as cause economic loss and symptoms

manifested in poor growth [18], loss of appetite and digestive

symptoms [19]. Although no specific number for economic losses

is known [15]. It is certain that millions of rupees are wasted owing

to lower milk yield, rejection of meat and edible offal’s, devaluation

of hides, delayed age of maturity and mortality, especially in

calves, and high production costs due to medication usage [20].

Infection with gastrointestinal parasites among the important

factors contributing to increased calf mortality [21]. Sub-clinical

nematode parasitic infection cause great economic losses and dam

milk production [22], because it affects the availability of nutrients,

the development of the digestive tract and (the appropriate

development of the immunity system against some diseases such

as parasitosis [23].

As a result, it is critical to reduce GIT parasites by improved

management [24], just as it is in developed nations, and information

of the parasite’s prevalence is required [25]. The frequency of GIT

parasites and related predisposing factors in buffalo and cow calves

in Rawalpindi rural districts are described in this research.

Materials and Methods

Ethical Approval

The research was conducted after approval of Institutional Ethical Committee.

Study Area

The study was conducted in the Rawalpindi region of Punjab’s rural areas (Chakri, Taxila, Kallar Syedan, Kahuta). It is situated in between latitude 33° 37’ 33.8052’’ N and 73° 4’ 17.1912’’ E with an average height of 602 m above mean sea level. Rawalpindi has a subtropical climate. During the study period, Rawalpindi received an annual rainfall of 989 mm. The temperature varied from -6°C to 48.8°C. The relative humidity varied from 18% to 89%.

Study Animals

The study was conducted on n=300 calves (150 each of buffalo and cow) were randomly picked for this purpose. Animals were categorized according to sex, i.e., male and females and age, i.e., animals of 1-6 months and 7-12 months. Age, species, sex, and management information (deworming, feeding method, housing conditions, mortality rate, and diseases problem) were all documented.

Collection of Faecal Samples

Fresh fecal samples of 300 calves (150 each of buffalo and cow) were collected randomly from different localities of Rawalpindi during February 2021 to September 2021. The faecal samples were taken directly from the animals’ rectums in self-sealed sterilized polythene hand gloves and were processed. Floatation technique was used for demonstrating nematode and cestode egg, as well as oocyst of coccidia and sedimentation technique, was used for detecting the trematode eggs. The ova/eggs of parasites were identified from their morphological characters. Eggs/oocysts per gram (EPG/OPG) of infection were determined by modified McMaster technique. The information gathered was evaluated using the chi-square approach and provided in tabular form.

Data Analysis

The data gathered from the study for the prevalence of parasitic infection were analyzed by Chi-square test.

Results

Predisposing Factors

It was discovered that most calves, particularly male buffalo calves, were ignored at the farmer’s level, and that they were feed / fodder that lactating animals refused. The majority of the calves developed pica, which resulted in worm infection. Although most farmers in the study region were aware of deworming, adoption was quite low. Only 35% of the farmers had their calves dewormed. The dosing rate and quality of the dewormed, on the other hand, were both problematic. It was also discovered that the farmers’ animals were not all dewormed at the same time. Calves letting down milk was a widespread behavior in the research region. The teats of the cows / buffaloes were not cleansed prior to being let down, and the calves consumed all of the excrement / dirt that adhered to the teats, which might lead to worm infection. The dewormers are both pricey and useless, according to the farmers’ complaint. It was common practice to use Kamila as a dewormer.

Gastrointestinal Parasite Prevalence in Buffalo and Cow Calves

Gastrointestinal parasites were found in 68.67% of buffalo

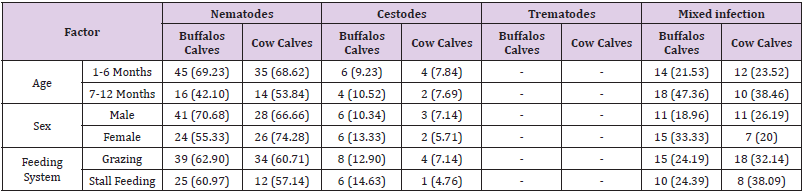

calves (103 out of 150). Overall, nematodes were shown to

have the highest prevalence, followed by mixed infection and

cestodes. Trematodes were not discovered in any of the calves.

Gastrointestinal parasites were observed to affect calves up to

6 months of age more (79.27%) than calves 7-12 months of age

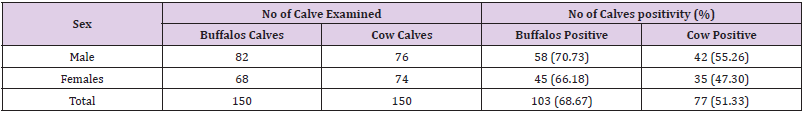

(55.88 %) (Table 1). Male buffalo calves were more impacted than

female buffalo calves when it came to gastrointestinal parasites.

(Table 2) Grazing calves were more likely than stall fed calves to

be infected with gastrointestinal parasites. Buffalos and Cow calves

(75.61%) and (73.68% ) is maximum as compare to stall feeding

of Buffalos and cow calves 60.29 % and 21%, respectively, were

discovered infected with nematodes and cestodes (Table 3). In

contrast buffalo calves had 62.90% and 12.90% of stall-fed calves

tested positive for nematodes and cestodes, respectively (Table

4). Male buffalo calves 70.73% were more impacted than female

buffalo calves when it came to gastrointestinal parasites 66.18%.

Strongyloides pappillosus, Toxocara vitulorum, Haemonchus

contortus, Ostertagia ostertagi, Bunostmum phleboyomum,

Oesophagostomum radiatum, Trichstrongylus spp., Nematodirus

spp., Cooperia spp., Trichstrongylus spp., Moniezia benedeni and

Moniezia expensa, regardless of the frequency of each species.

About 77 cow calves were discovered to have gastrointestinal

parasites out of 150. Calves between the ages of 1-6 months had

a greater incidence of 67.11%. However, worm infection was

discovered in 35.14% of calves aged 7-12 months (Table 1). Male

cow calves 55.26% were more impacted than female cow calves

when it came to gastrointestinal parasites 47.30% (Table 2).

Furthermore, grazing cow calf 73.68% were more affected then stall

feeding 28.38% (Table 3). Nematodes had the highest prevalence,

followed by mixed infection and cestodes (Table 4).

Discussion

In the world many research carried out on infect the buffaloes

and cow with parasites because, the buffaloes community is

assumption at 185 million, in Asia are 179 million of them [26].

The argument of pathogens is reliant on the number of it and

the nourishing status of the infecting buffaloes [27]. A serious

parasitized of internal parasites in animals basically leads to loss

of production [28]. These animals are considered among the most

productive domestic animals in the poor tropical countries and

are the major source of quality milk, with unique feed conversion

capacity, and they produce milk more cheaply than cattle [29].

Although the parasite does not harm the host to a greater extent

to cause a serious problem but in heavily infected and small aged

animals the parasite could prove harmful to the host by utilizing

the hosts digested food not only resulting in malnutrition but

also makes host weak and more susceptible to other diseases by

decreasing its immunity [30]. The distribution of gastro-intestinal

parasites was 74% [31].

Most common one was protozoa, and then nematode and

trematod, and the cestodes were the smallest infection rate among

all [32]. In current study the trematodes were not discovered in any

of the calves. Grazing calves were more impacted (73.68%) than stall

fed calves (28.38%). Further investigation revealed that nematodes,

cestodes, and mixed infection of nematodes and cestodes were

found in 62.71, 7.14, and 32.14% of grazed cow calves, respectively,

whereas nematodes, cestodes, and mixed infection of nematodes

and cestodes were found in 60.97%, 14.63%, and 38.09% of stall fed

calves, respectively. Strongyloides papillosus, Oesophagostomum

radiatum, Bunostomum phlebotomum, and Ostertagi ostertagi

were the most common species discovered, regardless of their

percent frequency [33]. The greater incidence of endo parasites in

this study might be linked to farmers’ carelessness in calf raising

and their failure to follow suggested calf management procedures

[34].

It was further reinforced, that calves are a neglected class

of animals at the farmer’s level [35], and that they are fed lowquality

food that nursing animals avoid [36]. The high frequency of

parasitism in calves in the field is mostly due to a lack of preventative

measures, such as frequent deworming using a quality dewormer

at the prescribed dose [37]. The results of this study are consistent

with those of [38] and [39], who found that buffalo calves have a

greater incidence of gastrointestinal parasites than cow calves.

The different in prevalence of gastrointestinal helminthiasis from

different parts of world could be due to the physiological status,

age, animal spp, climatic conditions [40] and the existing Managemental

practices at farm [41]. And the reflection of global climate

change that has been experienced over the last several decades,

which has altered distributions of organisms worldwide [42]. Also

the might be due to the variation in the sampling area and the

number of samples studied. The eggs found in this investigation

were nearly identical to those found in previous studies [43].

In cow and buffalo calves, they found Haemonchus contortus,

Ostertagia ostertagi, Bunostmum phlebotomum, Oesophagostomum

radiatum, Trichstrongylus spp. Nematodirus spp. Cooperia spp.

Moniezia benedeni, and Moniezia expensa eggs [44]. In buffalo and

cow calves, [45] discovered a 64.43 % frequency of gastrointestinal

parasites. Oesophagostomum radiatum, Mecistocirrus digitatus,

Bunostmum phlebotomum, strongyloides spp., and haemonchus

contortus were the most common species found [46], which accord

with the conclusions of this study. The disparity in occurrence might

be attributable to varying geo-climatic conditions and management

strategies in the studied area [47]. However, greater rates in buffalo

calves compared to cow calves may be due to variations in the two

species’ eating patterns and sanitary surroundings [48]. The greater

occurrence of gastro-intestinal parasites in calves up to 6 months of

age may be due to the calves’ proclivity to lick other animals, dirt,

and manure, among other things [49]. The responders agreed with

this reasoning, stating that newborn calves commonly lick the mud,

causing worm infection [50]. The technique of letting down milk

via a calf is prevalent in the field, but teat cleaning is done after the

milk is let down, and all the manure, urine, and other waste that

sticks to the dam’s teats is consumed by the calf, resulting in worm

infection [26].

The increased incidence of worm infection in buffalo male

calves might be related to farmers’ disregard of buffalo male calves’

management and preference for female upbringing, as heifer

farming was the prevalent practice in that area [46]. Farmers

were engaged in agriculture activities in the study area, and the

use of cow bullocks was common [51]. The low prevalence of

worm infestation in males could be due to a caring attitude [52].

Control of gastrointestinal parasitic infections in animals requires

a comprehensive knowledge of the disease epidemiology and

understanding of the pasture management, farm management

practices, and agro climatic conditions such as temperature and

rainfall [53]. The numbers of parasitic eggs and coccidial oocytes

developed inside the host animals vary depending on the parasite

species, level of host susceptibility, the health status of the animal,

and immunological status [54]. During this study, parasitic stages

of five different parasites were detected in the fecal samples. The

identified parasitic stages were eggs of hookworms (Bunostomum

spp.), whipworms (Trichuris spp.), amphistomes, cestodes

(Moniezia spp.), and oocytes of protozoans (coccidians). These

observations comply with the past records [54].

The greater worm infection rate in grazed calves compared to

stall fed calves might be due to calves taking up worm eggs produced

by diseased animals through faeces while grazing. [55] Backed up

this argument by pointing out that pasture contamination is only

due to eggs lost by adult animals during grazing. However, most

of the cattle in non-treated farms were open grazing animals and

they were almost never treated for any GI infections [27]. Grazing

often encourages entering of different parasitic stages into the

digestive tract of cattle through oral ingestion [16]. Fecal egg counts

are highly important as an indicator to decide the period that the

cattle have to be given deworming treatments [27]. This can also be

used after deworming treatments to investigate the effectiveness

of a particular anthelmintic [10]. Therefore, unnecessary costs

of veterinary services and drugs can be reduced [2]. When using

fecal egg counts, there are some limitations to determining the

significance of the prevalence of flukes [4].

The number of parasitic eggs per gram of feces is influenced

by the fecal consistency, total amount of feces produced, and time

of the day feces were collected [11]. When the feces are dried, the

parasitic eggs within the feces will be more concentrated [39].

The severity of gastrointestinal parasitic infections can be due

to the vulnerability of animals to internal parasites and the poor

immunity [20]. The prevalence rate and clinical diseases may

vary, based on different environmental factors in different areas.

The high prevalence of gastrointestinal nematodes and coccidian

oocytes has been reported in tropical regions including Sri Lanka,

with prevalence rates ranging from 20 to 96% [27]. Adult animals

are mostly immune, however calves became infected due to a rise

in the quantity of infectious larvae [31]. The presence of dams and

their calves on the pasture is likely to cause pasture contamination,

which is hazardous to the calves [14].

Conclusion

At the farmer level, the increased frequency of worm infection in cow and buffalo calves is mostly owing to the failure to follow recommended calf management procedures. Prophylactic procedures including deworming, hygiene measures, and food control can help to alleviate the condition. Future studies are required to evaluate the economic impact of GI parasites in the study area.

References

- Agrawal MC, Vohra S, Gupta S, Singh KP (2004) Prevalence of helminthic infection in domestic animals in Madhya Pradesh. J Vet Parasitol 18: 147-149.

- Babar A, Yousaf A, Fazilani SA, Jan MN (2021) Incidence of Bovine Anaplasma Marginale in Sindh, Pakistan. American Journal of Zoology 4 (4): 61-64.

- Awraris T, Bogale B, Chanie M (2012) Occurrence of gastro intestinal nematodes of cattle in and around Gondar town, Amhara regional state, Ethiopia. Acta Parasitol Glob 3(2): 28-33.

- Akbar M (1989) A study of gastric trematodes in buffaloes and taxonomy of the species of the genus paramphistomum MSc (Hons) Thesis, Deptt Parasitology, College of Veterinary Sciences, Lahore.

- Amir MI (1994) Studies on the incidence of gastrointestinal helminthes and comparative efficacy of anthelmintics in buffalo calves MSc (Hons) Thesis, Faculty of Veterinary Science, Uni Agri, Faisalabad.

- Babar A, Yousaf A, Sarki I, Subhani A (2021) Incidence of Bovine Brucellosis in Thatta, Sindh-Pakistan. Advances in Bioscience and Bioengineering 9(4): 92-95.

- Hailu D, Cherenet A, Moti Y, Tadele T (2011) Gastrointestinal helminth infections in small-scale dairy cattle farms of Jimma town, Ethiopia Ethiop. J Appl Sci Technol 2(1): 31-37.

- Iqbal MM (1987) Survey of gastrointestinal parasites of buffaloes in Faisalabad and evaluation of efficacy of Albandazole against these infections MSc (Hons) Thesis Deptt Clin Med Surg Univ Agri, Faisalabad.

- Baloch S, Yousaf A, Shaheen S, Shaheen S, Sarki I, et al. (2021) Study on the Prevalence of Peste Des Petits Virus Antibodies in Caprine and Ovine through the Contrast of Serological Assessments in Sindh, Pakistan. Animal and Veterinary Sciences 9(5): 131-135.

- Bilawal AM, Babar A, Panhwar IM, Hal K, Farooq MM, et al. (2021) Detection of Brucella Abortus in Caprine and Ovine by Real-Time PCR Assay. Animal and Veterinary Sciences 9 (5): 141-144.

- Chaudhry NI, MS Durrani, T Aziz (1984) The incidence of gastrointestinal parasites in buffaloes and calves of Azad Kashmir Pakistan. Vet J 4(1): 60-61

- Gupta A, Dixit AK, Dixit P, Mahajan C (2012) Prevalence of gastrointestinal parasites in cattle and buffaloes in and around Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh. J Vet Parasitol 26(2): 186-188.

- Habib F, Jabbar A, Shahnawaz R, Memon A, Yousaf A, et al. (2019) Prevalence of hemorrhagic septicemia in cattle and buffaloes in Tandojam, Sindh, Pakistan. Online J Anim Feed Res 9(5): 187-190.

- Hussain A, Bilal M, Habib F, Gola BA, Muhammad P, et al. (2019) Effects of low temperature upon hatchability and chick quality of Ross-308 broiler breeder eggs during transportation Online. J Anim Feed Res 9(2): 59-67.

- Baqir Y, Sakhawat A, Yousaf A, Tabbasum R, Awais T, et al. (2021) Therapeutic management of milk fever with retained placenta in Holstein Friesians cow in a private dairy farm at Sheikhupura, Punjab-Pakistan. Multidisciplinary Science Journal e2021015.

- Haque M, Singh J, Singh NK, Juyal PD, Singh H, et al. (2011) Incidence of gastrointestinal parasites in dairy animals of Western plains of Punjab. J Vet Parasitol 25: 168-170.

- Fikru R, Teshale S, Reta D, Yosef K (2006) Epidemiology of gastro intestinal parasites of ruminants in Western Oromia Ethiopia. Int J Appl Res Vet Med 4: 51-57.

- Anwar AH, SN Buriro, A Phulan (1995) A hydatidosis veterinary perspective in Pakistan. The Veterinarian, p. 11-14.

- Baqir Y, Yousaf A, Soomro AG, Jamil T (2021) Sorex araneusis a pathogenic microbial threat in commercial poultry farms. Multidisciplinary Science Journal 3: e2021016.

- Gibbs HC (1979) Relative importance of winter survival of nematodes in pasture and infected carrier calves in a study of parasitic gastroenteritis in calves. Am J Vet Res 40: 227-231.

- Hussain A, Yousaf A, Mushtaq A (2018) Prevalence of mycoplasma gallisepticum in ross-308 broiler breeder through the contrast of serological assessments in Pakistan. J Dairy Vet Anim Res 7(1): 00185.

- Bilal MQ, Hameed A, Ahmad T (2009) Prevalence of gastrointestinal parasites in buffalo and cow calves in rural areas of Toba Tek Singh, Pakistan. J Anim Plant Sci 19(2): 67-70.

- Irfan M (1984) Key note address on effects of parasitism in lowering livestock population Pakistan. Vet J 4(1): 25-27.

- Biu A, Maimunatu A, Salamatu AF, Agbadu ET (2009) A fecal survey of gastrointestinal parasites of ruminants on the university of Maiduguri research farm. Int J Biomed Health Sci 5(4): 175-179.

- Habib F, Tabbasum R, Awais T, Sakhawat A, Khalil R, et al. (2021) Prevalence of Bovine Tropical Theileriosis in Cattle in Quetta Balochistan-Pakistan. Arch Animal Husb & Dairy Sci 2(1) AAHDSMSID000540.

- Jamali MK, Tabbasum R, Bhutto AL, Sindhu, Ramzan M, et al. (2021) Prevalence of Toxoplasma Gondii in Sheep and Goats in Multan (Punjab), Pakistan. Arch Animal Husb & Dairy Sci 2(4): AAHDSMSID000541.

- Javed S, R Ahmad, R Anjum, SU Rehman (1993) Prevalence of endo parasites in buffaloes and cattle Pakistan. Vet J 13(2): 88-89.

- Jamali MK, Yousaf A, Sarki I, Babar A, Sharna SN (2021) Assessments of Prevalence of Brucellosis in Camels Through the Contrast of Serological Assessments in South Punjab, Pakistan. American Journal of Zoology 4(4): 65-68.

- Keyyu JD, Kassuku AA, Msalilwa LP, Monrad J, Kyvsgaard NC (2006) Cross-sectional prevalence of helminth infections in cattle on traditional, small-scale and large-scale dairy farms in Iringa district, Tanzania Trop. Anim Health Prod 30(1): 45-55.

- Mourad MI, SA Abdullah, TE Allowy (1985) Comparative study on the gastrointestinal parasitism of cattle and buffalo with special reference to haematological changes at Assiut Governorate. Assiut Vet Med J 15: 163-166.

- Khan A, Yousaf A, Shahnawaz R, Latif Bhutto A, Baqir Y, et al. (2021) Snake Bite Case in Holstein Friesian Cattle at Private Dairy Farm in Hyderabad, Sindh OA. J Ani Plant Husbandry 2(1): 180005.

- Khan A, Rind R, Shoaib M, Kamboh AA, Mughal GA, et al. (2016) Isolation, identification and antibiogram of Escherichia coli from table eggs. J Anim Health Prod 4(1): 1-5.

- Kakar MN, JK Kakarsulemankhel (2008) Prevalence of endo (trematodes) and ectoparasites in cows and buffaloes of Quetta, Pakistan Pakistan. Vet J 28(1): 34-36.

- Pritchard RK, S Ranjan, C Trudeau, C Piche (1990) Epidemiology of bovine nematode parasites in Eastern Canada In: Guerrero and WHD Leaning (Edt.)., epidemiology of Bovine nematode parasites in the Americas, Procee MSD Symposium, 13-17, Salvador Bahia, Brazil Vet Learning systems, Trenton, NY USA, p 89-96.

- Regassa F, Sori T, Dhuguma R, Kiros Y (2006) Epidemiology of gastrointestinal parasites of ruminants in Western Oromia, Ethiopia. Int J Appl Res Vet Med 4(1): 51-57.

- Jamra N, Das G, Haque M, Singh P (2014) Prevalence and intensity of strongyles in buffaloes at Nimar region of MP. Int J Agric Sci Vet Med 2(1): 54-57.

- Masood FS, A Majid (1989) Five year survey on ascariasis in buffaloes and cow calves in Multan Division Pakistan. Vet J 4(2): 63-65.

- Mir MR, Chishti MZ, Rashid M, Dar SA, Katoch R, et al. (2013) Point prevalence of gastrointestinal helmintheasis in large ruminants of Jammu India. Int J Sci ResPubl 3(3): 1-3.

- Ranjan S, RK Pritchard, C Trudeau, C Piche (1992) Epidemiological study of parasite infection in cow-calf herd in Quebec. Vet Paristol 42: 281-293.

- Qureshi AW, Tanveer A (2009) Seroprevalence of fasciolosis in buffaloes and humans in some areas of Punjab, Pakistan. Pak J Sci 61(2): 91-96.

- Kumar S, Das G, Nath S (2013) Incidence of gastrointestinal parasitism in buffalo in Central Madhya Pradesh. Vet Pract 14(1): 16-19.

- Raza AM, Iqbal Z, Jabbar A, Yaseen M (2007) Point prevalence of gastrointestinal helminthiasis in ruminants in southern Punjab, Pakistan. J Helminthol 81: 323-328.

- Soomro AG, Arain MB, Yousaf A, Rubab F, Sharna SN, et al. (2021) Therapeutical Management of Canine Babesiosis in German Shepherd Bitch at Hyderabad, Sindh. American Journal of Zoology 4(4): 57-60.

- Yousaf A, Abbas M, Laghari RA, Hassan J, Rubab F, et al. (2017) Epidemiological investigation on outbreak of brucellosis at private dairy farms of Sindh, Pakistan Online. J Anim Feed Res 7(1): 09-12.

- Yousaf A, Sarki I, Babar A, Khalil R, Sharif A, et al. (2021) Detection of Foot and Mouth Disease Viruses in Cattle using Indirect Elisa and Real Time PCR. J Vet Med Animal Sci 4(2): 1086.

- Soomro AG, Yousaf A, Fawad M, Fatima S, Jamali MK (2021) Therapeutic Management of Tetanus in a Kamori Male Goat. American Journal of Zoology 4(4): 69-71.

- Yousaf A, Tabbasum R, Awais T, Sakhawat A, Khan S, et al. (2021) Prevalence of Toxoplasma Gondii in Domestic Breeds of Goats in Faisalabad, Punjab. Animal and Veterinary Sciences 9(5): 145-148.

- Soulsby EJL (1982) Helminths, Arthropods and Protozoa of the Domesticated animals (7th)., The English Language Book Soc & Bailliare Tindall, London.

- Tabbasum R, Awais T, Sakhawat A, Khalil R, Sharif A, et al. (2021) Prevalence and Risk Factors of Theileriosis in Goat and Sheep in Lahore. J Vet Sci Res 6(2): 000215.

- Telila C, Abera B, Lemma D, Eticha E (2014) Prevalence of gastrointestinal parasitism of cattle in East Showa Zone, Oromia regional state, Central Ethiopia. J Vet Med Anim Health 6(2): 54-62.

- Swarnakar G, Bhardawaj B, Sanger B, Roat K (2015) Prevalence of gastrointestinal parasites in cow and buffalo of Udaipur district, India. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci 4(6): 897-902.

- Rehman K, K Javed, MT Tunio, Z H Kuthu (2009) Passive surveillance of gastrointestinal parasites in buffaloes of Mandi Bahauddin and Gujrat Districts of the Punjab. The J Anim Plnt Sci 19(1): 17-19.

- Yousaf A, Laghari RA, Shoaib M, Ahmad A, Kanwar Kumar Malhi, et al. (2016) The prevalence of brucellosis in Kundhi buffaloes in District Hyderabad, Pakistan. J Anim Health Prod 4(1): 6-8.

- Yousaf A, Soomro AG, Subhani A, Fazilani SA, Jan MN, et al. (2021) Detection of Toxoplasma Gondii Infection in Goats and Sheep using the Indirect Haemagglutination Test in Peshawar, Kyber Pakhtunkhwa-Pakistan. J Vet Med Animal Sci 4(2): 1087.

- Zajac AM, Conboy GA (2012) Veterinary Clinical Parasitology (8th Edn.)., John Wiley & Sons, Inc, UK, pp. 3-170.

Research Article

Research Article