ABSTRACT

The need for identifying and using effective solvents for extraction of bioactive ingredients of high antioxidant properties from plant sources is paramount. The aim of this work is to establish the best solvent for extraction of bioactive ingredients as well as the part of moringa plant that is richest in antioxidants properties. The seeds, leaves, pods and coats of moringa plant were obtained, cut, ground and sieved with 40 mm mesh and separately extracted using six different solvents (acetone, ethyl acetate, methanol, ethanol, water and chloroform) at ratio 1:10 for 72 h. The efficiency of each solvent was determined as percent extractive value. The first two highest solvent extracts for each of the seeds, leaves, pods and coats of moringa plant were analyzed for antioxidant properties. It was observed that moringa seeds had the highest extractive values in all the solvents used while moringa pods had the lowest extractive values. The solvent extraction efficiency decreases in order of acetone, ethyl acetate, ethanol, methanol, water and chloroform. There was significant difference at p<0.05 in the extractive values of the seeds, leaves, pods and coats of moringa plant in all the solvents used. There were significant differences at p < 0.05 in the total flavonoid, total phenol, DPPH, iron chelation assay and ferric reducing antioxidant power of raw sample, ethanol extract and ethyl acetate extract of moringa leaves as well as all the antioxidant properties for raw sample, acetone extract and ethanol extract of moringa coats. Seeds and leaves of moringa were richest in antioxidant properties.

Keywords: Extractive Values; Antioxidant Properties; Bioactive Ingredients; Solvents; Moringa Plant

Introduction

Antioxidants are molecules that fight free radicals in human

body [1]. Antioxidants cause protective effect by neutralizing free

radicals which are toxic byproducts of natural cell metabolism.

Research is increasingly showing that antioxidant rich foods and

herbs have health benefits. Medicinal herbs are the richest sources

of antioxidants compounds [2]. Antioxidants are biomolecules

which tackle and destroy free radicals and scavenge diseases [3].

Sagar, et al. and Shao, et al. reported that green plants are chief

sources of natural antioxidants, and they are capable of tackling

free radicals [3-5]. Moringa oleifera belongs to the single genus

family Moringaceae and it is most studied of the thirteen species of

Moringa trees [6,7]. It is a deciduous tree that grows up to 12 m tall

with an umbrella-shaped crown and grows extremely fast which

can reach up to 4 m in its first year. Its leaves are alternate bi or

tri-pinnate, 20-70 cm long. Leaflets are usually oval, rounded at the

tip, and 1-2cm long and they are dark green in colour with almost

whitish in the lower surface [8,9].

Fahey, 2005 reported that the leaves of Moringa oleifera are

the most nutritious part of the plant, being a significant source of

vitamin B6, vitamin C, pro-vitamin A as beta- carotene, flavonoids, 46 antioxidants, magnesium and protein among other nutrients.

The plant is called “Zogale” in Hausa, “ Ewe Igbale” in Yoruba, “Ikwe

Oyibo” in Ibo and “Egelengedi” in Idoma while its English name is

Bean oil tree or drumstick tree or miracle tree or “Mother’s Best

Friend” [6,10,11]. Though a lot of research works have been done on

moringa plant [10,12-16]. but there is little, or no work done on the

effect of solvents in extracting phytochemicals from the seeds, coats,

pods and leaves of the plant. Therefore, the focus of this research

work is to evaluate the potency of solvents in extracting bioactive

ingredients from seeds, coats, pods and leaves of moringa plant as

well as to investigate and compare the antioxidant properties of the

first two highest yield solvent-extracts with that of the raw sample

with a view of establishing which of the moringa plant parts (seeds,

leaves, pods and coats) is richest in phytochemical constituents and

antioxidant properties.

Materials and Methods

Source of Materials

The seeds, coats, pods and leaves of Moringa oleifera were collected from a compound of a building at Ajagbale Street, Oka, Ondo City, Ondo State, Nigeria. All chemicals used were of the analytical grade with the highest purity available (<99.5%) and procured from Sigma Aldrich, USA.

Preparation and Extraction of Seeds, Coats, Pods and Leaves of Moringa Plant

The different parts of moringa plant were cut into smaller pieces for easy air-drying. The dried samples were ground separately using electric blending machine (Solitarire Mixer Grinder VTCL Heavy Duty 750 Watts) and each part was sieved with 40 mm mesh size. The powdered samples were divided into portions, packed in air tight containers labelled appropriately prior to extraction. Each sample was extracted separately with each solvent (acetone, chloroform, ethyl acetate, ethanol, methanol and water) at ratio 1:10 for 72 h during which it was intermittently shaken on a shaking orbit machine The resulting mixture was filtered through a 0.45 μm nylon membrane filter. The extracts were desolventised to dryness under reduced pressure at 40 oC by a rotary evaporator (BUCHI Rotavapor, Model R-124, Germany). Weight of extract obtained was used to calculate the percentage yield of extract in each solvent and the dry extracts were stored in a refrigerator (4 0C) prior to analysis [17-19].

Determination of Antioxidant Property

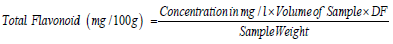

Total Flavonoid

0.1g of extract was weighed into a sample bottle; 10 mL of 80% methanol was added and allowed to soak for 2 hours. 0.4 mL of the solution was measured into a 10 mL volumetric flask, 1.2 mL of 10% sodium hydroxide, 1.2 mL of 0.2 M concentrated sulphuric acid and 3 mL of 3 M sodium nitrate were added. 4.2 mL of distilled water was used to make it up. The absorbance was read using 6850 UV spectrophotometer at wavelength 325 nm [20].

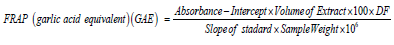

Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP)

0.1g of extract was weighed into a sample bottle; 10 mL of 80% ethanol was added. 2.5 mL sodium phosphate buffer (0.2 M Na2PO3, pH 6.6) and 2.5 mL of 1% potassium ferricyanide were added and incubated at 50˚C for 20 minutes. 2.5 mL of TCA (trichloroacetic acid) was added to stop the reaction. 2.5 mL of the aliquot was taken and diluted with 2.5 mL distilled water and 0.5 mL of 0.1 % ferric chloride was added and allowed to stand for 30 minutes in the dark for color development. The absorbance was read using 6850 UV/Visible spectrophotometer at wavelength 700 nm [21].

DF: Dilution factor. If not diluted, then DF = 1

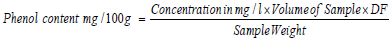

Total Phenol

0.1g of extract was weighed into a sample bottle; 10 mL of distilled water was added to dissolve. 1 mL of the solution was pipetted into a test tube and 0.5 mL of 2 N Folin-Ciocalteu reagent and 1.5 mL of 20 % sodium carbonate solution was added. The solution was allowed to stand for 2 hours and the absorbance was read using a 6850 UV/Visible spectrophotometer at wavelength 765 nm. Garlic acid solution was used as standard viz 0.5 mg, 1 mg, 2 mg, 4 mg, 6 mg, 8 mg and 10 mg [22].

DF: Dilution factor. If not diluted, then DF = 1

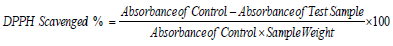

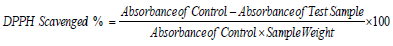

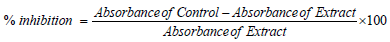

DPPH (2, 2-Diphenyl-1-Picrylhydrazyl) Scavenging

0.1g of extract was weighed into a sample bottle and 10 mL of ethanol was added, stirred for 15 minutes and allowed to stand for 2 hours. 1.5 mL of the extract was pipetted into a test tube and 1.5 mL of DPPH solution was added. The 6850 UV/Visible spectrophotometer was zeroed with ethanol as the blank solution. The absorbance/ optical density of the control (DPPH solution) was read. The absorbance of the test sample was read at 517 nm. [23].

DF: Dilution factor. If not diluted, then DF = 1

Iron (Fe2+) Chelation Assay

0.1g of extract was weighed into a sample bottle, 150 μL of 500 μM FeSO4 was added. 168 μL of 0.1M Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) and 218 μL of saline solution was added. 100 μL of the solution was taken and incubated for 5 minutes, before addition of 13 μL of 0.25% 1, 10-phenanthroline. The absorbance was read using 6850 UV/ Visible spectrophotometer at wavelength 510 nm [24].

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance tests were performed using SPSS (v. 20, IBM SPSS Statistics, US) at p < 0.05 by means of one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by LSD post hoc multiple comparison and the experimental results were expressed as mean ± standard mean deviation of three replicates.

Results and Discussion

Extractive Values of Solvent Extracts of Leaves, Seeds Pods and Coats of Moringa Plant

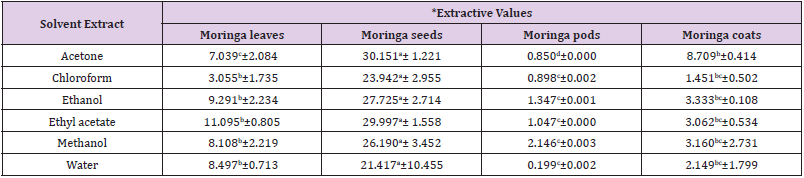

The extractive values (% yield) of leaves, seeds, pods and coat

moringa plant using acetone, chloroform, ethanol, ethyl acetate,

methanol and water are contained in Table 1. The result showed

that the percentage yield of moringa leaf extract was 11.095±0.805

in ethyl acetate, 9.291±2.234 in ethanol, 8.497±0.713 in water,

8.108±2.219 in methanol, 7.039±2.084 in acetone and 3.055 ±

1.735 in chloroform. The percentage yield of moringa pod extract

was 2.146±0.003 in methanol, 1.347±0.001 in ethanol, 1.047±0.000

in ethyl acetate, 0.898±0.002 in chloroform, 0.850±0.000 in acetone

and 0.199±0.002 in water. The percentage yield of moringa coat

extract was 8.709±0.414 in acetone, 3.333±0.108 in ethanol,

3.160±2.731 in methanol, 3.062±0.534 in ethyl acetate, 2.149±1.799

in water and 1.451±0.502 in chloroform. The percentage yield of

moringa seed extract was 30.151±1.221 in acetone, 29.997±1.558 in

ethyl acetate, 27.725±2.714 in ethanol, 26.190±3.452 in methanol,

23.942±2.955 in chloroform and 21.417±10.455 in water.

In each of the solvent used, there was a significant difference

at p<0.05 in the extractive values of the seeds, leaves, pods and

coats of moringa plant. In all the solvents used for extraction, it

was observed that the extractive value (%) was highest in moringa

seed and least in moringa pod. All the solvents used had the first

two highest extractive values in moringa seeds and leaves except

acetone that had its first two highest extractive values in moringa

seeds and coats. According to Alachaher, et al. 2018 [21], there are

quite number of factors in which extraction of bioactive compounds

depends. The selection of solvent system largely depends on the

specific nature of the bioactive compounds being targeted. Also,

different solvent systems are available to extract the bioactive

compounds from natural products. Extraction efficiency is affected

by the chemical nature of phytochemicals, the extraction method

used, sample particle size, the solvent used, as well as the presence

of interfering substances. Under the same extraction time and

temperature, solvent and composition of sample are known as the

most important parameters [21].

Table 1: Extractive value of solvent extracts of moringa plant.

Note: * = Result values are expressed as mean value of triplicate determinations ± standard mean deviation

Different letter in the same row showed significant difference (p<0.05).

Antioxidant Properties of Solvent Extracts of Leaves, Seeds, Pods and Coats of Moringa Plant

Antioxidant properties were carried out on the plant raw sample and the first two solvent extracts with the highest extractive values. The antioxidant properties of raw sample, ethanol and ethyl acetate extracts of leaves; acetone and ethyl acetate extracts of seeds; methanol and ethanol extracts of pods as well as acetone and ethanol extracts of coats of moringa plant were examined and these are presented in Table 2 to Table 5. The antioxidant properties of raw sample, ethanol and ethyl acetate extracts of moringa leaves is depicted in Table 2. The concentration (mg/100g) of total flavonoid in moringa leaves ranged between 0.122±0.001 - 0.332±0.001 with ethanol extract had the highest concentration of 0.332±0.001 mg/100g, followed by ethyl acetate extract with concentration of 0.268±0.002 mg/100g while the powdered raw sample has the least concentration of 0.122±0.001 mg/100g. The total phenol concentration (mg/100g) in moringa leaves ranged between 0.181±0.002 - 0.349±0.003 with ethanol extract having the highest concentration of 0.349±0.003 mg/100g, followed by ethyl acetate extract with concentration of 0.251±0.001 mg/100g while the powdered raw sample had the least concentration of 0.181±0.002 mg/100g.

Table 2: Antioxidant properties of moringa leaves.

Note: * = Values are expressed as mean value of triplicate determinations ± standard mean deviation; GAE =Garlic Acid Equivalent Different letter in the same row showed significant difference (p<0.05).

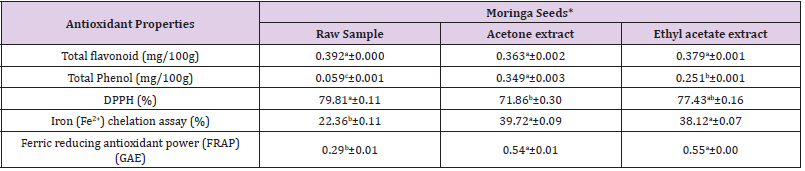

Table 3: Antioxidant properties of moringa seeds.

Note: * = Values are expressed as mean value of triplicate determinations ± standard mean deviation; GAE =Garlic Acid Equivalent

Different letter in the same row showed significant difference (p<0.05).

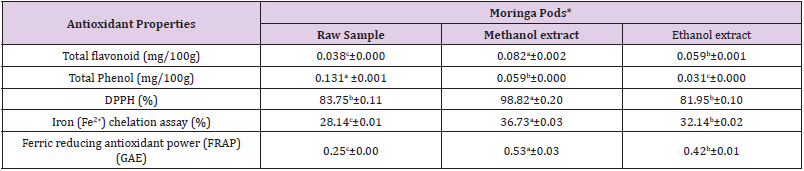

Table 4: Antioxidant properties of moringa pods.

Note: * = Values are expressed as mean value of triplicate determinations ± standard mean deviation;GAE =Garlic Acid Equivalent

Different letter in the same row showed significant difference (p<0.05).

Table 5: Antioxidant properties of moringa pods.

Note: * = Values are expressed as mean value of triplicate determinations ± standard mean deviation; GAE =Garlic Acid Equivalent

Different letter in the same row showed significant difference (p<0.05)

The percentage DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) scavenging activity of powdered raw sample showed the highest value of 89.25±0.21% followed by ethanol extract of 63.10±0.30% while ethyl acetate extract had the lowest value of 57.45±0.16%. The ethyl acetate extract of moringa leaves exhibited the highest reducing power of concentration of 0.87±0.02 GAE followed by ethanol extract which had concentration of 0.47±0.00 GAE while the powdered sample had the least concentration of 0.32±0.01GAE. There were significant differences at p < 0.05 in the total flavonoid, total phenol, DPPH, iron chelation assay and ferric reducing antioxidant power of raw sample, ethanol extract and ethyl acetate extract of moringa leaves. The antioxidant properties of raw sample, acetone and ethyl acetate extracts of moringa seeds is displayed in Table 3. The total flavonoid concentration (mg/100g) of moringa seeds ranged from 0.363±0.002 - 0.392±0.000 in which the powdered sample had the highest concentration of 0.39±0.000 mg/100g, followed by ethyl acetate extract with concentration of 0.379±0.001 mg/100g while the acetone extract has the least concentration of 0.363±0.002 mg/100g.

There was no significant difference (p < 0.05) in the total

flavonoid content of raw sample, acetone extract and ethyl acetate

extract of moringa seeds. In moringa seeds, the total phenol

concentration (mg/100g) was between 0.059±0.001 - 0.349±0.00.

The ethanol extract had the highest concentration while the

powdered raw sample had the lowest concentration of total

phenol. The ethyl acetate extract of moringa seeds had total phenol

concentration of 0.251±0.001 mg/100g. There was significant

difference (p < 0.05) in the total phenol concentration of raw

sample, acetone extract and ethyl acetate extract of moringa seeds.

The DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) radical scavenging

activity of powdered raw sample of moringa seeds had the highest

activity of 79.81±0.11% followed by ethyl acetate extract with DPPH

activity of 77.43±0.16% while acetone extract showed the lowest

activity of 71.86±0.30%. There was significant difference (p < 0.05)

in the DPPH (2, 2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) radical scavenging activity of raw sample, acetone extract and ethyl acetate extract

of moringa seeds. The iron chelation activity (%) ranged between

22.36±0.11 - 39.72±0.09 with the lowest and highest concentration

in raw sample and acetone extract respectively while the ethyl

acetate had iron chelation activity of 38.12a±0.07%.

There was no significant difference (p < 0.05) in iron chelating

activity of acetone extract and ethyl acetate extract of moringa

seeds. The ethyl acetate extract of moringa seeds exhibited the

highest ferric reducing antioxidant power of concentration

of 0.55±0.00 GAE followed by acetone extract which had

concentration of 0.54±0.01 GAE while the powdered sample had

the least concentration of 0.29 ±0.01 GAE. There was no significant

difference (p < 0.05) in ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP)

of acetone extract and ethyl acetate extract of moringa seeds.

The antioxidant properties of raw sample, methanol and ethanol

extracts of moringa pods is shown in Table 4. The concentration

(mg/100g) of total flavonoid of moringa pods ranged between

0.038±0.000 - 0.082±0.002 with methanol extract having the

highest concentration and the powdered sample having the least

concentration while the total flavonoid concentration of ethanol

extract of moringa pod was 0.059±0.001 mg/100g. There was

significant difference (p < 0.05) in total flavonoid concentration of

raw sample, methanol extract and ethanol extract of moringa pods.

The total phenol concentration (mg/100g) of moringa pods was

between 0.031±0.000 - 0.131±0.001.

The highest and lowest total phenol concentration were found in

ethanol extract and raw sample of moringa pods respectively while

methanol extract had total phenol concentration of 0.059±0.000

mg/100g. There was significant difference (p < 0.05) in total

phenol concentration of raw sample, methanol extract and ethanol

extract of moringa pods. For DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl)

scavenging activity of moringa pods, it was observed that methanol

extract showed the highest value of 96.82±0.20% followed by

powdered raw sample which had 83.75±0.11% while ethanol extract

showed the lowest value of 81.95±0.10%. There was no significant

difference (p < 0.05) in DPPH scavenging activity of raw sample and

ethanol extract of moringa pods. The iron chelating activity (%) of

moringa pods ranged from 28.14±0.01 - 36.73±0.03 with the lowest

and highest concentration in methanol extract and raw sample

accordingly and that of ethanol extract was 32.14±0.02%. There

was significant difference (p < 0.05) in iron chelating activity of raw

sample, methanol extract and ethanol extract of moringa pods.

The ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) of methanol

extract of moringa pods exhibited the highest reducing power of

0.53±0.03 GAE, followed by ethanol extract of 0.42±0.01 GAE while

the powdered raw sample had least concentration of 0.25±0.00

GAE. There was significant difference (p < 0.05) in ferric reducing

antioxidant power of raw sample, methanol extract and ethanol

extract of moringa pods. The antioxidant properties of raw sample,

acetone extract and ethanol extract of moringa coat is presented in

Table 5. The total flavonoid concentration (mg/100g) of moringa

coats ranged from 0.049±0.000 - 0.317±0.002 with acetone extract

had the highest concentration and the powdered raw sample had

the least concentration while ethanol extract had total flavonoid

of 0.258±0.001 mg/100g. The concentration (mg/100g) of total

phenol of moringa coat was between 0.031±0.000 - 0.118±0.002.

The acetone extract and ethanol extract had the lowest and highest

concentration while the raw sample of moringa coat had total

phenol concentration of 0.063±0.001mg/100g.

The DPPH of ethanol extract moringa coat showed highest activity of 95.20±0.12 % followed by powdered sample which had activity of 85.07±0.09% while acetone extract showed the lowest activity of 72.13±0.10%. The iron chelating activity (%) of moringa coats was between 11.18±0.00 - 44.91±0.04. Ethanol extract had the highest iron chelating activity while acetone extract had the lowest and that of raw sample was 30.34±0.02 %. The ferric reducing antioxidant power of acetone extract of moringa coats exhibited the highest reducing power of 0.85±0.05 GAE followed by ethanol extract of 0.64±0.03 GAE while the powdered raw sample has the least concentration of 0.32±0.01 GAE. There were significant differences (p < 0.05) in all the antioxidant properties considered for raw sample, acetone extract and ethanol extract of moringa coats [25-28].

Conclusion

The moringa seeds are richest in bioactive ingredients and this is followed by moringa leaves while the least bioactive ingredients are found in moringa pods. The solvent extraction efficiency of bioactive ingredients in moringa plant decreases in the order of acetone, ethyl acetate, ethanol, methanol, water and the least is chloroform. The utilization of acetone, ethyl acetate, ethanol and methanol in extracting bioactive ingredients of high antioxidant activities from the seeds and leaves of moringa plant is economical and effective. Further scientific investigation can be conducted using acetone, ethyl acetate, ethanol and methanol extracts of seeds and leaves of moringa plant as antioxidants or preservative in edible oils and their antioxidative potentials can be compared with synthetic antioxidants such as butylated hydroxyl anisole (BHA), butylated hydroxyl toluene (BHT) etc. in edible oils.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest with any institution/organization.

References

- Wikipedia (2021). Antioxidant.

- Adeleke AR (2021) Extractive value, phytochemical screening and antioxidant properties of Moringa (seeds, coats, pods and leaves) and plantain flower extracts, A first degree project submitted to the Department of Chemistry, University of Medical Sciences, Ondo, Ondo State, Nigeria: pp: 21-23.

- Pham-Huy LA, Hua H, Chuong P (2008) Free radicals, antioxidants in disease and health, International Journal of Biomedical Science 4(2): 89-96.

- Sagar FM, Vivek OA, Dayaramji KD (2018) Phytochemical screening and antioxidant potential of some plant materials, International Journal of Life Sciences 6(1): 239-247.

- Shao H, Li-Ye C ,Zhan-Hua L, Cong-Min R (2008) Primary antioxidants free radical scavenging and redox signaling pathways in higher plant cells, International Journal of Biological Sciences 4(1): 8-14.

- Osayemwenre E (2015) Phytochemical and antioxidant evaluation of Moringa oleifera (Moringaceae) leaf and seed 11(2): 1-57.

- Olson ME (2001) Introduction to the moringa family. In: Fuglie LJ. (Editor). The miracle tree: The multiple attribute of moringa, Church World Service, Senegal, pp: 11-28.

- Tolani, J (2013) Potentials of Moringa oleifera for health improvement and wealth creation. A lecture delivered at 800 seater Auditoriun at Rufus Giwa Polytechnic, Owo, Ondo-State on December 10th, 2013.

- Iqbal S, Bhanger MI (2006) Effect of season and production location on antioxidant activity of Moringa oleifera leaves grown in Pakistan. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 19: 544-551.

- Makkar HP, Francis G, Becker K (2007) Bioactivity of phytochemicals in some lesser-known plants and their effects and potential applications in livestock and aquaculture production systems. Animal 1 (9): 1371-1391.

- Fuglie LJ (2001) Vernacular names of Moringa oleifera. In: The miracle tree: The multiple attribute of moringa, Church World Service, Senegal, pp 159-162.

- Arabshahi DS, Devi DV, Urooj A (2007) Evaluation of antioxidant activity of some plant extracts and their heat, pH and storage stability, Food Chemistry 100: 1100-1105.

- Abdulkarima SM, Long K, Lai OM, Muhammad SKS, Ghazali HM (2007) Frying quality and stability of high-oleic Moringa oleifera seed oil in comparison with other vegetable oils, Food Chemistry 105: 1382-1389.

- Soliva CR, Kreuzer M, Foidl N, Foidl G, Machmüller A, et al. (2005)Feeding value of whole and extracted Moringa oleifera leaves for ruminants their effects on ruminant fermentation in vitro, Animal Feed Science Technology 118: 47-62.

- Sarwatt SV, Kapange SS, Kakengi AMV (2002) Substituting sunflower seed-cake with Moringa oleifera leaves as a supplemental goat feed in Tanzania, Agroforestry Systems 56(3): 241-247.

- Lockett CT, Calvert CC, Grivetti LE (2000) Energy and micronutrient composition of dietary and medicinal wild plants consumed during drought. In: Study of rural Fulani, northeastern Nigeria. International Journal Food Science and Nutrition 51: 195-208.

- Arawande JO, Aderibigbe AS (2020) Stabilization of edible oils with bitter leaf (Vernonia amygdalina) and water bitter leaf (Struchium sparganophora) extracts, SAR Journal of Medical Biochemistry 1(1): 9-15.

- Arawande JO, Akinnusotu A, Alademeyin JO (2018) Extractive value and phytochemical screening of ginger (Zingiber officinale) and turmeric (Curcuma longa) using different solvents, International Journal of Traditional and Natural Medicine 8(1): 13-22.

- Bopitiya D, Madhujith T (2014) Efficacy of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) peel extracts in suppressing oxidation of white coconut oil used for deep frying. Tropical Agricultural Research 25(3): 298-306.

- Mahajan RT, Badujar SB (2008) Phytochemical investigations of some laticiferous plants belonging to Khandesh region of Maharashtra, Ethnobotanical Leaflets 12: 1145-1152.

- Alachaher FZ, Dali S, Dida N, Krouf D (2018) Comparison of phytochemical and antioxidant properties of extracts from flaxseed (Linum usitatissimum) using different solvents, International Food Research Journal 25(1): 75-82.

- Hagerman A, Muller I, Makkar H (2000) Quantification of tannins in tree foliage, A laboratory manual, Vienna: FAO/IAEA, pp: 4-7.

- Teraos KK, Shinamoto N, Hirata M (1988) Determination of 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) Scavenging, Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 37: 793-798.

- Oboh HA, Omoregie IP (2011) Total phenolics and antioxidant capacity of some Nigerian beverages, National Journal of Basic and Applied Science 19(1): 68-75.

- Ashley A, Thiede BS, Sheri ZC (2016) Nutrition and health information Sheet: Phytochemicals PhD center for nutrition in schools, Department of Nutrition University of California, Davis.

- Balamurugan V, Velurajan S, Sheerin FA (2019) A guide to phytochemical analysis. In: International Journal of Advance Research And Innovative Ideas In Education IJARIIE-ISSN(O)-5: 2395-4396.

- Fahey JW (2005) Moringa oleifera: A review of the medical evidence for its nutritional, therapeutic and prophylactic properties. Trees for Life Journal 1: 5.

- Thangapazham RL (2016) Phytochemicals in wound healing. Advance wound care, New Rochelle 5(5): 230-241.

Research Article

Research Article