ABSTRACT

Objective: The aim of this systemic review and meta-analysis was to examine the relationship between intestinal parasitic infection and anemia among pregnant women in Ethiopia. We include six studies in different regions of Ethiopia. We have done this study focusing on intestinal parasitic infection.

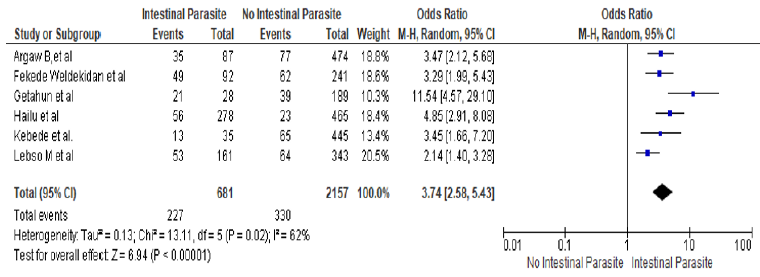

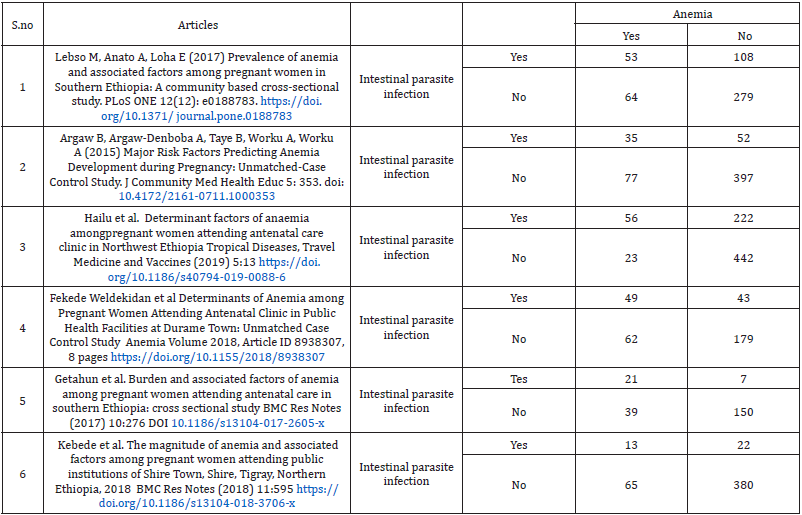

Materials and Methods: The databases searched were PUBMED and Advanced Google Scholar. on reference manager software reporting intestinal parasitic infection and anemia among pregnant women. Three researchers were carried out the data extraction and assessed independently the articles for inclusion in the review using riskof- bias tool guided by PRISMA checklist. The combined adjusted Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated using random effect model. Results: six observational studies involving 2838 participants, 557 pregnant women who have anemia were included. The combined effect size (OR) for anemia comparing pregnant women who have intestinal parasitic infection versus pregnant women women who did not have intestinal parasitic infection was 3.74 (ORMH = 3.74, 95% CI 2.58-5.43] Heterogeneity: Tau² = 0.13; Chi² = 13.11, df = 5 (P = 0.02]; I² = 62% Test for overall effect: Z = 6.94 (P < 0.00001]. No publication bias was observed (Egger’s test: p = 0.074, Begg’s test: p = 0.091]. 23.99% (681] pregnant women have intestinal parasitic infection during current pregnancy. In all studies, the proportion of anemia among pregnant women who have intestinal parasitic infection during current pregnancy was 227 (33.33%). Conclusions: The likelihood of anemia among pregnant women is approximately four times higher among pregnant women who had intestinal parasitic infection than who did not have the infection in Ethiopia.Keywords: Determinant of Anemia; Intestinal Parasitic Infection, Meta-Analysis; Systematic Reviews; Ethiopia

Introduction

Pregnant women with Hemoglobin level less than 11 g/dl are considered to be anemic [1]. In the world, 56 million pregnant women are anemic [2] In Africa the magnitude of anemia among pregnant women was 57.1% [3]. Prevalence of anemia among pregnant women in Ethiopia is 63% and in east Africa countries 55% in Kenya, 58% in Sudan and Eritrea 55.3% [4]. Different factors might leads to anemia among pregnant women. Geohelminth infections during pregnancy were associated with maternal anemia. Hookworm infection causes anemia among pregnant women and it also aggravates anemia in pregnant women [5]. Infections by helminthes leads to malnutrition, iron deficiency anemia, and increased vulnerability to other infections in infected pregnant women [6]. Other recent studies in Ethiopia have reported prevalence of anemia ranging from 16.6% in a facilitybased study in Gondar, northwest Ethiopia to 56.8% in Gode town, Eastern Ethiopia [6 ,7]. Prior studies in Ethiopia have reported significant associations between anemia in pregnancy and parasitic infections [e.g. schistosomiasis, hookworm infection], prior use of contraceptives, use of iron supplementation, birth spacing/ intervals, parity and gravidity, educational attainment, age, body weight, trimester of pregnancy and wealth status [6 -18]. Despite there are many researches done on anemia among pregnant women in Ethiopia, but data on intestinal parasitic infection and anemia among pregnant women in Ethiopia is not adequate. This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted to assess the relationship between intestinal parasitic infection and anemia among pregnant women in Ethiopia.

Methods

Search Approach and Appraisal of Studies

Studies were Searched using primary key terms of

‘determinant of anemia ‘, ‘anemia ‘, ‘intestinal parasitic infection

‘, ‘ intestinal parasitic infection and anemia ‘, ‘Ethiopia ‘ and to

generate additional keywords for the search we were used the

following search strategies; ‘ intestinal parasitic infection + anemia

+pregnant women + Ethiopia through Electronic databases on

reference manager software.

a) The databases searched were PUBMED and Advanced Google

Scholar

b) References of studies that meet eligibility criteria were used to

identify similar articles

Inclusion Criteria

a) All Studies that were assessed the relationship between

intestinal parasitic infection and anemia.

b) The outcome of interest was anemia

c) The study reported the percentage of anemia according to

intestinal parasitic infection

d) Meet quality assessment

Exclusion Criteria

a) Studies that were published in languages other than English,

b) Included participants with anemia not dichotomized as anemia

and no anemia,

c) Included participants with intestinal parasitic infection not

dichotomized as yes and no

d) Studies conducted not in Ethiopia were also excluded to avoid

the combination of studies that were not comparable.

Data Extraction

Three researchers were carried out the data extraction The extracted information were the name of the author, study area, the number and percentage of anemia, the number and percentage of intestinal parasitic infection.

Risk of Bias and Quality Assessment

To assess external and internal validity, a risk-of-bias tool was

used. The tool has seven items:

1. Random sequence generation [selection bias],

2. Allocation concealment [selection bias],

3. Blinding of participants [performance bias],

4. Blinding of outcome assessment [detection bias],

5. Incomplete outcome data [attrition bias],

6. Selective reporting [reporting bias] and

7. Other bias. All of these items are rated based on the

author’s subjective judgment given responses to the preceding

seven items rated as low, moderate or high risk.

Three reviewers assessed independently the articles for

inclusion in the review using risk-of-bias tool and guided by

PRISMA checklist. A discrepancy that would face by reviewers on

selection of studies and data extraction was resolved by discussion

Additionally, all potential confounding variables were controlled by

multivariable analysis in all included studies.

Measures

Outcome variable pregnant women with Hemoglobin level less than 11 g/dl are considered to be anemic [1].

Statistical Analysis

The necessary information was extracted from each original study by using a format prepared in Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and transferred to Meta-essential and Revman software for further analysis. Pooled effect size of anemia was estimated from the reported proportion of eligible studies using RevMan V.5.3 software. Forest plots were generated displaying MH odd ratio with the corresponding 95% CIs for each study. As the test statistic showed significant heterogeneity among studies Heterogeneity: Tau² = 0.13; Chi² = 13.11, df = 5 [P = 0.02 ]; I² = 62% ] the Random effects model was used to estimate the DerSimonian and Laird’s pooled effect.

Assessment of Publication Bias

Funnel plot asymmetry and Egger’s test was used to check the publication bias.

Results

Selected Studies

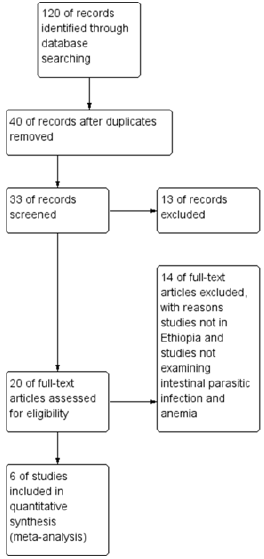

Figure 1 shows selection process of studies 120 of records identified through database searching 40 of records after duplicates removed 33 of records screened and 13 of records excluded, 20 of full-text articles assessed for eligibility and 14 of full-text articles excluded, with reasons, studies not in Ethiopia and studies not examining intestinal parasitic infection and anemia and finally 6 of studies included in quantitative synthesis [meta-analysis].

Characteristics of Included Studies

Six observational studies involving 2838 participants, 557 pregnant women who have anemia were included. In all studies, the proportion of anemia among pregnant women who have intestinal parasitic infection during current pregnancy was 227 [33.33%].

Pooled Effect Size

The odds of anemia among pregnant women who had intestinal parasitic infection is 3.74 times higher than those pregnant women who did not have intestinal parasitic infection [ORMH = 3.74, 95% CI 2.58-5.43] Heterogeneity: Tau² = 0.13; Chi² = 13.11, df = 5 [P = 0.02]; I² = 62% Test for overall effect: Z = 6.94 [P < 0.00001] (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Forest plot for the association between intestinal parasite infection and anemia among pregnant women in Ethiopia

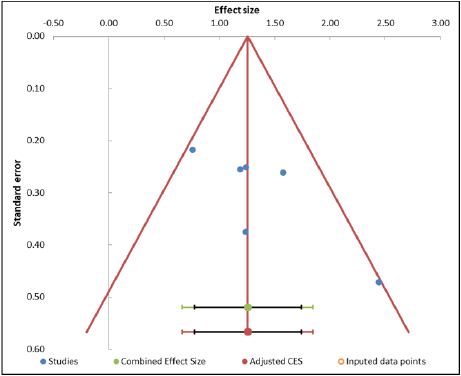

Assessment of Publication Bias Analysis

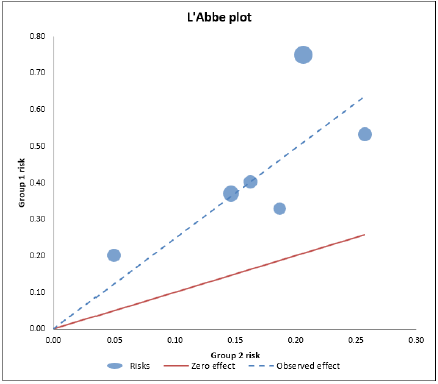

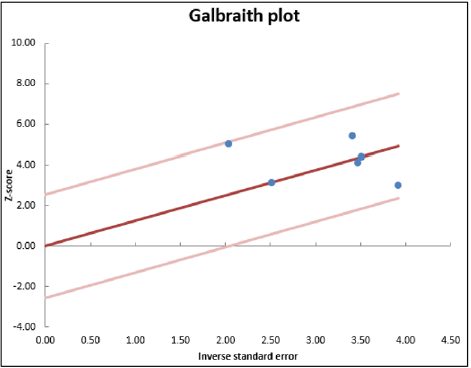

No publication bias was observed [Egger’s test: p = 0.074, Begg’s test: p = 0.091]. The below ‘Abbe plot showed that all studies effect size is above the zero-effect size. The below Galbraith plot showed that 95% of the studies effect size lie between the two-color lines and this indicates there is no outlier of effect size. (Tables 2 &3) (Figures 3-5).

Figure 3: Funnel plot for the association between intestinal parasite infection and anemia among pregnant women in Ethiopia.

Figure 4: ‘Abbe plot for the association between intestinal parasite infection and anemia among pregnant women in Ethiopia.

Figure 5: Galbraith plot for the association between intestinal parasite infection and anemia among pregnant women in Ethiopia.

Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, pregnant women who were infected with intestinal parasite were 3.74 times more likely to be anemic than who were not infected by any intestinal parasite and this is consistent with previous studies, [6, 19-24]. The worm in the intestine may cause intestinal necrosis and blood loss as a result of the attachment to the intestinal mucosa and chronic infections lead to iron deficiency and anemia resulting from the excessive loss of iron [25]. Therefore, an effective intervention packages need to reduce anemia among pregnant women through iron supplementation, anthelmintic treatment and dietary diversification in the study area [26]. Our finding is similar with other previous study in Ethiopia [27] this possibly happen because most anemic pregnant women who are living in Ethiopia were farmers, bare foot walking is common among Ethiopian farmers, and the chance to be exposed for soil transmitted parasite is very high. Besides this, the low environmental sanitation status may also aggravate the chance of intestinal parasite infection. Parasitic diseases were known to play as a major contributing factor to anemia in pregnancy. For example, blood loss caused by hookworm puts mothers at high risk of iron deficiency anemia [28]. Our finding is similar with many previous studies conducted in Ethiopia and other developing countries that have shown the strong association of intestinal parasitic infection with anemia in pregnant women [23,28-29,30-33] Parasitic infection has a devastating effect on the level of Hgb and causes anemia since they affect iron absorption by the intestine and consumes the red blood cells [34]. There was a strong significant association between intestinal parasitic infection and anemia in pregnant women.in previous studies [35], in Southern Ethiopia [19], Ghana [34], Nigeria [36], and Venezuela [37], Durame Town Ethiopia [38]. , in Yirgalem and Hawassa cities, Dessie town and Canada [27, 39. 33 ]., Shire Town , Tigray, Northern Ethiopia [40], in Shalla Woreda of Oromia region In Ethiopia [16]. This is expected as intestinal parasites, apart from their competition for nutrients, are known to cause blood loss, loss of appetite reduced motility of food through the intestine and damage to the wall of the intestine leading to mal-absorption of nutrients.

Conclusion

The likelihood of anemia among pregnant women is approximately four times higher among pregnant women who had intestinal parasitic infection than who did not have the infection.

Data Availability

All data are included in the paper

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ Contributions

1. Kaleab Tesfaye Tegegne, Eleni Tesfaye Tegegne, and Mekibib

Kassa Tessema was responsible for conceptualization, project

administration, software, supervision, and development of the

original drafting of the manuscript.

2. Kaleab Tesfaye Tegegne, Eleni Tesfaye Tegegne, and Mekibib

Kassa Tessema and Abiyu Ayalew Assefa were participated in

quality assessment of articles, methodology, validation, and

screening of research papers

3. All authors contributed with data analysis, critically revised

the paper, and agreed to be accountable for their contribution.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the primary authors of the included articles.

Competing of Interest

The authors have declared that there is no competing interest.

Funding

Not any funding received for this work.

References

- Makhoul Z, Taren D, Duncan B, Pandey P, Thomson C, et al. (2012) Risk factors associated with anemia, iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia in rural Nepal pregnant women. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Pub Heal 43(3): 735-746.

- OueÂdraogo S, Koura KG, Accrombessi KM, Bodeau-Livinec F, Mssougbodji A, et al. (2012) Maternal anemia at first antenatal visit: prevalence and risk factors in a malaria-endemic area in Benin. Am J Trop Med Hyg 87(3): 418-424.

- Horque M, Horque E, Kader SB (2009) Risk factor of anaemia in pregnancy in rural Kuwazula- Natal South Africa, implication for health education and promotion. SA Fam Pract 51(1): 68-72.

- Tefera G (2014) Determinants of anemia in pregnant women with emphasis on intestinal helminthic infection at Sher- Ethiopia Hospital, Ziway, Southern Ethiopia. Immunology and Infectious Diseases 2(4): 33 - 39.

- (2001) World health organization. Iron deficiency anaemia: assessment, prevention and control. A guide for programme managers. Geneva.

- Stoltzfus RJ, Dreyfuss ML, Chwaya HM, Albonico M (1997) Hookworm control as a strategy to prevent iron deficiency. Nutr Rev 55: 223 ±232.

- Argaw B, Argaw-Denboba A, Taye B, Worku A, Worku A (2015) Major Risk Factors Predicting Anemia Development during Pregnancy: Unmatched-Case Control Study. J Community Med Health Educ 5: 353.

- Brooker S, Hotez PJ, Bundy DAP (2008) Hookworm-Related Anaemia among Pregnant Women: A Systematic Review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2: e291.

- Bethony P, Brooker S, Hotez P (2006) Soil-transmitted helminth infections: ascariasis, trichuriasis, and hookworm. Lancet 367: 1521-1532.

- Rodríguez-Morales AJ, Barbella RA, Case C, Arria M, Ravelo M, et al. (2006) Intestinal parasitic infections among pregnant women in Venezuela. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2006: 23125.

- Yatich NJ, Yi J, Agbenyega T, Turpin A, Rayner JC, et al. (2009) Malaria and intestinal helminth co-infection among pregnant women in Ghana: prevalence and risk factors. Am J Trop Med Hyg 80: 896-901.

- Alem M, Enawgaw B, Gelaw A, Kena T, Seid M, et al. (2013) Prevalence of anemia and associated risk factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care in Azezo Health Center Gondar town, Northwest Ethiopia. J Interdiscipl Histopathol 3: 137-144

- Gyorkos TW, Gilbert NL (2014) Blood Drain: Soil-Transmitted Helminths and Anemia in Pregnant Women. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 8: e2912.

- Tay KSC, Nani EA, Walana W (2017) Parasitic infections and maternal anaemia among expectant mothers in the Dangme East District of Ghana. BMC Res Notes 10.

- Tadesse Hailu, Simachew Kassa, Bayeh Abera, Wondemagegn Mulu, Ashenafi Genanew (2019) Determinant factors of anaemia among pregnant women attending antenatal care clinic in Northwest Ethiopia Tropical Diseases, Travel Medicine and Vaccines 5:13.

- Akinbo FO, Olowookere TA, Okaka CE, Oriakhi MO (2017) Co-infection of malaria and intestinal parasites among pregnant women in Edo State, Nigeria. J Med Trop 19: 43-48.

- Rodríguez-Morales AJ, Barbella AR, Case C, Melissa Arria M, Ravelo M, et al. (2006) Intestinal Parasitic Infections among Pregnant Women in Venezuela. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2006: 23125.

- Fekede Weldekidan, Mesfin Kote, Meseret Girma, Negussie Boti, Teklemariam Gultie (2018) Determinants of Anemia among Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Clinic in Public Health Facilities at Durame Town: Unmatched Case Control Study Anemia.

- Sisay Eshete Tadesse, Omer Seid, Yemane G/Mariam, Abel Fekadu, Yitbarek Wasihun, et al. (2017) “Determinants of anemia among pregnant mothers attending antenatal care in Dessie town health facilities, northern central Ethiopia, unmatched case -control study. PLoS ONE 12(3).

- Awoke Kebede, Hadgu Gerensea,Freweyni Amare, Yared Tesfay, Girmay Teklay (2018) The magnitude of anemia and associated factors among pregnant women attending public institutions of Shire Town, Shire, Tigray, Northern Ethiopia, 2018 BMC Res Notes (2018) 11: 595.

- De Maeyer EM, Dallman P, Gurney JM, Hallberg L, Sood SK, et al. (1989) Preventing and controlling iron deficiency anemia through primary health care, a guide for health administrators and programme managers.

- Balarajan Y, Ramakrishnan U, Ozaltin E, Shankar AH, Subramanian SV (2011) Anaemia in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet 378 (9809): 2123-2135.

- (2008) World health organization. Worldwide prevalence of anemia 1993±2005. WHO Global Database on Anemia. Geneva: World health organization.

- Benoist BD, McLean E, Egll I, Cogswell M (2008) Worldwide prevalence of anemia 1993-2005: WHO global database on anemia. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Stephenson LS, Latham MC, Ottesen EA (2000) Malnutrition and parasitic helminth infections. Parasitology 121: 23-38.

- Melku M, Addis Z, Alem M, Enawgaw B (2014) Prevalence and Predictors of maternal anemia during pregnancy in Gondar, Northwest Ethiopia: an institutional based cross-sectional study. Anemia 2014.

- Alene KA, Dohe AM (2014) Prevalence of Anemia and Associated Factors among Pregnant Women in an Urban Area of Eastern Ethiopia. Anemia 2014.

- Kefyalew AA, Abdulahi MD (2014) Prevalence of anemia and associated factors among pregnant women in an urban area of eastern Ethiopia. Anemia 2014: 561-567.

- Desalegn S (1993) Prevalence of anaemia in pregnancy in Jima town, southwestern Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J 31(4): 251-258.

- Abriha A, Yesuf ME, Wassie M (2014) Prevalence and associated factors of anemia among pregnant women of Mekelle town: a cross sectional study. BMC Res Notes 7: 888.

- Bekele A, Tilahun M, Mekuria A (2016) Prevalence of anemia and its associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal Care in Health Institutions of Arba Minch town, Gamo Gofa Zone, Ethiopia: a crosssectional study. Anemia 2016: 1073192.

- Gebre A, Mulugeta A (2015) Prevalence of anemia and associated factors among pregnant women in north western Zone of Tigray, northern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. J Nutr Metab 2015: 165430.

- Gedefaw L, Ayele A, Asres Y, Mossie A (2015) Anemia and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal Care Clinic in Wolayita Sodo Town Southern Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci 25(2): 155-162.

- Getachew M, Yewhalaw D, Tafess K, Getachew Y, Zeynudin A (2012) Anaemia and associated risk factors among pregnant women in Gilgel gibe dam area, Southwest Ethiopia. Parasites Vectors 5: 296.

- Kedir H, Berhane Y, Worku A (2013) Khat chewing and restrictive dietary behaviors are associated with anemia among pregnant women in high prevalence rural communities in eastern Ethiopia. PLoS One 8(11): e78601.

- Obse N, Mossie A, Gobena T (2013) Magnitude of anemia and associated risk factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care in Shalla Woreda, west Arsi Zone, Oromia region, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci 23(2): 165-173.

- Alemu T, Umeta M (2015) Reproductive and obstetric factors are key Predictors of maternal anemia during pregnancy in Ethiopia: evidence from Demographic and health survey (2011). Anemia 2015: 649815.

- Zerfu TA, Umeta M, Baye K (2016) Dietary diversity during pregnancy is associated with reduced risk of maternal anemia, preterm delivery, and low birth weight in a prospective cohort study in rural Ethiopia. Am J Clin Nutr.

- Lebso M, Anato A, Loha E (2017) Prevalence of anemia and associated factors among pregnant women in Southern Ethiopia: A community based cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 12(12): e0188783.

- Meseret A, Bamlaku E, Aschalew G, Tigist K, Mohammed S, Yadessa O, et al. (2013) Prevalence of anemia and associated risk factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care from Gondar town, Northwest Ethiopia 2018. J Inter Histo 1(3): 137-144.

Review Article

Review Article