Introduction

In this study we investigate staff perceptions of patient safety culture in Greek primary care settings, and we analyze how different characteristics of patient safety culture might influence overall patient safety perceptions. Institute of Medicine (IOM) in its report titled “Improving Diagnosis in Health Care.”[1] describes diagnostic error as “failure to create an accurate and timely explanation of the patient’s health problem or communicate that explanation to the patient.” Other formal definitions of diagnostic errors have been proposed in the past [2-4]. Primary care is a highrisk area for medical errors because of its main features (i.e., first contact care, continuity, comprehensiveness, and coordination) [5]. Physicians are frequently faced with heavy patient loads and are compelled to make choices under pressure [6]. In primary care, undifferentiated presenting symptoms are the norm for both common and uncommon illnesses, which are usually benign and self-limiting. The diagnosis is generally made through several sessions of care and over a period of time [7,8]. Physicians must carefully balance the risk of missing a serious disease against the prudent use of limited and costly referral and diagnostic resources. As a result, diagnostic mistakes that cause patient harm as a result of inappropriate or delayed testing or treatment have become a worldwide concern.

Cancer, pulmonary embolism, and coronary artery disease were among the most common diagnostic mistakes recorded in a study of primary care physicians [9,10]. Outpatient and inpatient mistakes linked to pulmonary embolism (4.5%), medication reactions (4.5%), lung, colorectal, and breast malignancies (3.9%, 3.3%, and 3.1%, respectively), as well as acute coronary syndrome (3.1%) and stroke (2.6%) were identified according to a study of US internal medicine professionals [6]. Malignant diseases were also the most prevalent diagnosis in a survey of 181 medical malpractice conducted in the United States [11]. A study of 1000 negligence claims against UK medical practitioners found that the most common diagnostic mistakes were infections, injuries, and malignancy [12]. Malpractice claims, on the other hand, are more likely to entail diagnoses that are more serious or dangerous if not diagnosed accurately and promptly. Because of the errors that have been discovered in many health-care institutions in the past, most health-care organizations advise countries to establish patientsafety regulations.

The Institute of Medicine, in particular, mandates that healthcare institutions maintain patient safety in all of their operations [13]. In a similar vein, the European Council Recommendation on Patient Safety, Prevention, and Control outlined the advantages of taking general safety precautions when caring for the sick [14]. The council noted in its report that health institutions that do not adhere to patient safety suffer a variety of expenditures and place a strain on available resources [15]. Health institutions, on the other hand, can adopt patient safety protocols, particularly for individuals with chronic illnesses like diabetes and cancer. Patient safety programs [16,17] include a variety of activities in addition to medicine that are aimed at assisting patients in health facilities in their rehabilitation. Enhancing the safety culture among healthcare personnel should be part of such initiatives. The following definition of safety culture is provided by the Advisory Committee on the Safety of Nuclear Installations [18], which may easily be applied to the context of patient safety in health care: ‘‘The safety culture of an organization is the product of individual and group values, attitudes, perceptions, competencies, and patterns of behavior that determine the commitment to, and the style and proficiency of, an organization’s health and safety management”.

Medical professionals in all settings should be aware of and practice these values and beliefs in order to promote patient well-being and favorable results [19]. In addition, executives and managers should be involved in Patient Safety initiatives in order to develop effective means of fostering the culture in health institutions [20]. Various methods and quantitative instruments have been developed in this area to assess healthcare environments in terms of safety and quality, particularly in the hospital setting [21]. Concerns have been raised in recent years regarding medical mistakes in basic health care and the need to establish a safer environment for patients [22-24]. In primary care settings, a few publications have been published that use methods to measure patient safety culture [25-31]. From 2010 until 2018, Greece was supervised by the International Monetary Fund. Primary health care has experienced several modifications during the last eight years. The creation of a single primary health care provider (PEDY), a family doctor and the electronic prescribing were the most crucial of these reforms [32]. Therefore, it is challenging to investigate the level of primary care services provided in terms of quality and safety using a specialized and validated questionnaire. This kind of study took place for the first time in Greek primary units and mainly aims to evaluate patient safety culture based on health professionals’ perspectives, utilizing the validated Greek version of Medical Office on Patient Safety Culture survey tool (G-MOSPSC) [33]. Additional objects of the study are to investigate the extent to which the various components of a patient safety culture predict health professionals’ overall perceptions of patient safety, as well as the strong and weak areas of safety culture

Materials and Methods

MSOPSC Measurement Tool

This questionnaire was designed as a self-assessment tool for healthcare professionals and includes questions about their perceptions of patient safety and healthcare quality. Researchers from all around the world have verified and used it [34,35]. It includes 38 questions that assess 10 areas of patient safety culture, nine questions about “Patient Safety and Quality Issues four items relating to “Information Exchange with Other Settings”, and four items relating to “Average Overall Ratings on Quality and Patient Safety”. The overall proportion of respondents in a PHU who answered “Strongly agree”/“Agree” or “Always”/“Most of the time” on items with five-point response scales is recognized as a percent positive response. Because a negative response on a negatively phrased item is interpreted as a positive response, the proportion for negatively phrased items is equal to the overall percentage of respondents within a PHU who answered, “Strongly disagree”/”Disagree” or “Never”/”Rarely. The percent of overall positive results for the components “Patient Safety and Quality Issues” and “Information Exchange with Other Settings” were calculated differently from the other survey items. The percent of overall positive score for these 13 items is determined by the sum of the three alternative responses that indicate the lowest frequency of occurrence. Scores of higher than 75% are considered to be favorable markers of safety. The questionnaire was translated from English to Greek and evaluated in a pilot research, which indicated that all dimensions and questions should be kept, with the exception of the dimension “Information Exchange with Other Settings,” which was removed owing to a high non-response rate and non-applicability.

Study Design

Random stratified sampling was carried out among the primary care units of Attica’s first health area in Greece. In terms of services provided and health professionals’ specializations, twelve out of 78 PHUs were chosen in a representative manner. Participants were chosen at random from the twelve health care institutions. The responders required to be a member of a multidisciplinary team who provided direct and indirect help to the patient, had worked in the unit for at least 30 days, and had worked at least 20 hours per week. Respondents who did not satisfy the aforementioned criteria were excluded from the research. The survey was presented to the chosen participants in a sealed envelope during working hours and gathered in a sealed envelope two to three days later. Participants were advised not to share the questionnaire with one another to avoid peer pressure. The intermediary was not included as a member. The MSOPSC was created with the intention of referring to all professionals [15]. However, the pre-test revealed that staff who were not directly involved in patient care did not always reply to questions about actual patient care (i.e., managers and administrators). As a result, 469 people completed the survey (60% response rate), and 10 questions were excluded, with less than half of the items were answered.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was conducted with IBM SPSS 21.0 software (IBM Corp. Released 2012.Ibm SPSS for Windows, Version 21.0 Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). The absolute numbers (n) and percentages (%) were estimated for the categorical variables. Arithmetic mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) were estimated for continuous variables. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test showed that the scores of patient safety culture composites did not have normal distribution, therefore Spearman’s correlation coefficient was performed to investigate the relationship between safety culture composites with the overall rating of respondents with patient safety and quality. All tests were two-tailed, and the significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

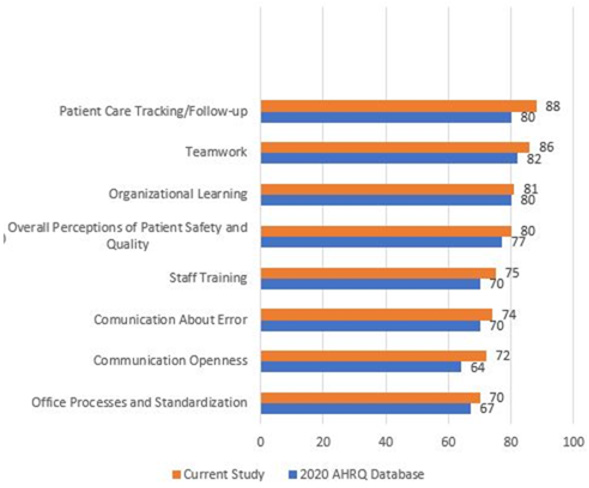

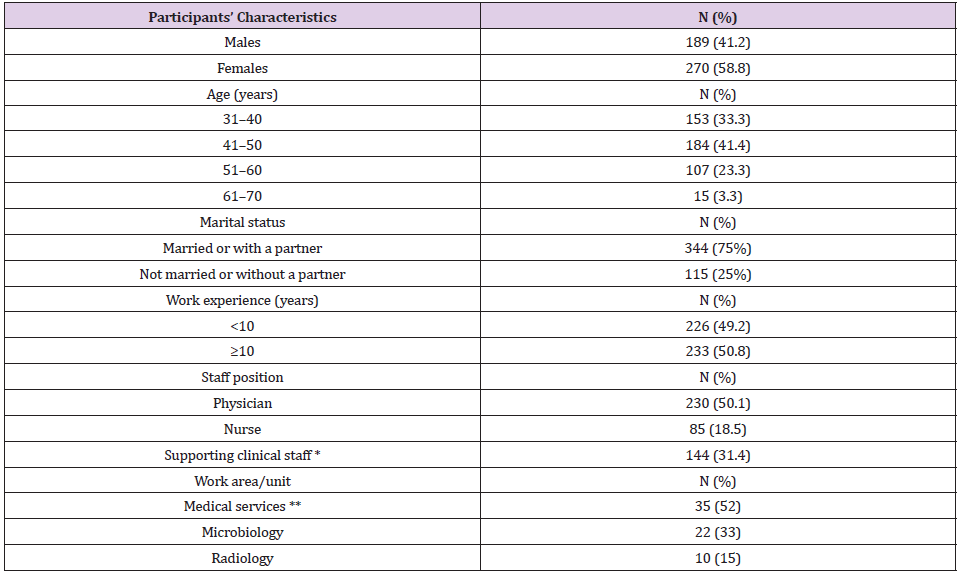

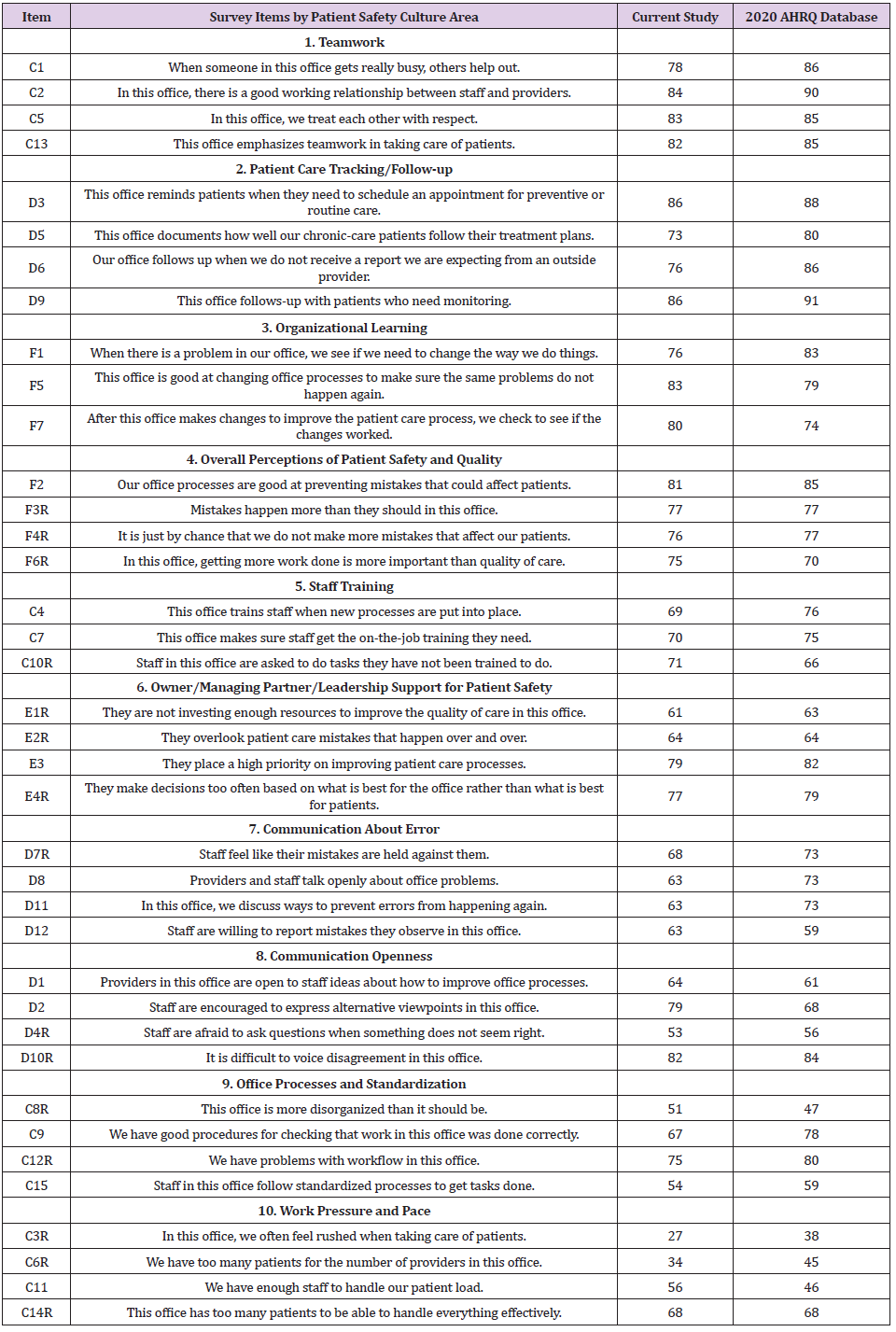

Female professionals (58.8%) aged between 31 and 50 years (74.7%), married or living with a partner (64%), and with a bachelor’s degree (75%) predominated. As for the professional category, 230 (50.1%) were physicians, 85 (18.5%) were nurses, and 144 (31.44%) were supporting clinical staff (radiographer, health supervisor, and nurse assistant). Regarding work experience and the work area of the respondents, 50.8% had more than 10 years of experience, 35% worked in medical departments (family practice, pathology, and pediatrics), 33% worked in microbiology, and 15% worked in radiology departments (Table 1). The most highly ranked composites by the respondents were “Teamwork” (82% positive rating), “Patient Care Tracking/Follow-up” (80%), “Organizational Learning” (80%), and “Overall Perception of Patient Safety and Quality” (78%). “Staff training” (70% of positive responses), “Communication About Errors” (70%), “Office Processes and Standardization” (67%), and “Communication Openness” (64%) followed. The lowest scores were for “Owner/ Managing Partner/Leadership Support for Patient Safety” (62%) and “Work Pressure and Pace” (46%) (Figure 1 and Table 2).

Figure 1: Comparison of patient safety culture scores for Greek primary care centers with U.S Medical Offices.

Table 1: The kind of medical services given at 12 primary healthcare facilities, as well as the demographic characteristics of the survey respondents.

Table 2: Item-level results for Greek primary care centers (N = 78) and U.S. medical offices (N = 1.475).

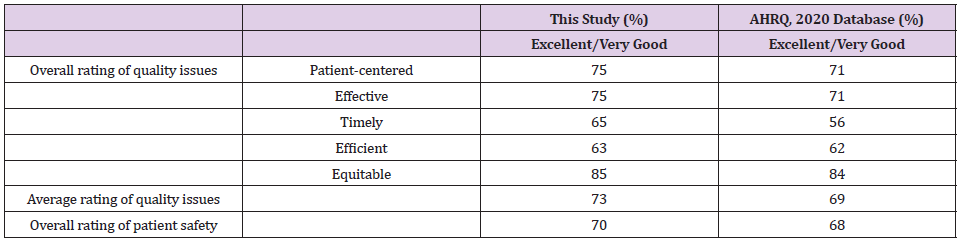

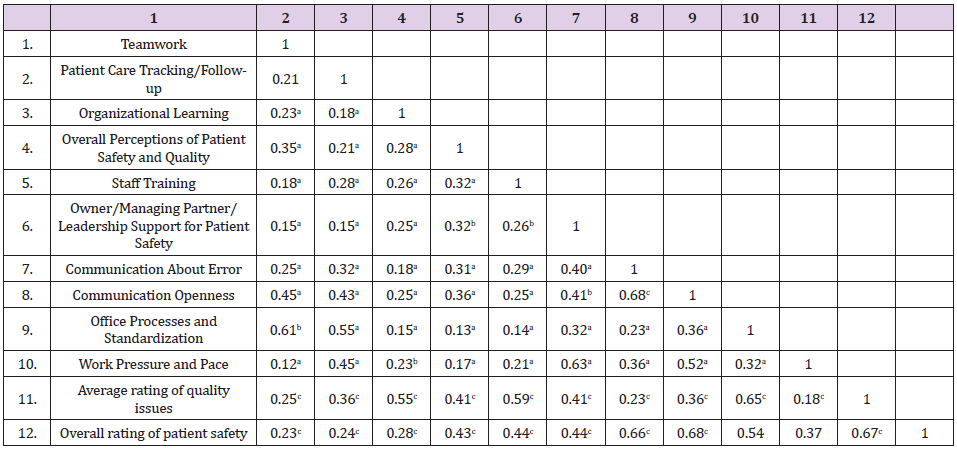

The overall ratings of quality and patient safety received positive scores, with 73% and 70% of participants returning ”very good” or “‘excellent’” responses, respectively (Table 3). The results of Kolmogorov-Smirnov test showed that the scores of Average Rating of Quality Issues (z = 0.14, P = 0.002) and Overall Rating of Patient Safety (z = 0.08, p = 0.036) did not have a normal distribution. Spearman’s correlation coefficient test showed a significant positive correlation between Average Rating of Quality Issues and Overall Rating of Patient Safety composites (r = 0.67, p = 0.001). The scores of communications about error (r = 0.66, P = 0.001) and communication openness (r = 0.68, p = 0.001) dimensions had significant positive correlations with . Furthermore, the dimensions of Organizational Learning (r = 0.55, p=0.001), Staff Training (r = 0.59, p=0.001) and Office Processes and Standardization (r=0.65, p=0.001) seems to relate significantly to Average Rating of Quality Issues composite (Table 4).

Table 3: Overall rating of quality and safety in the current study (n = 459) as compared with the 2020 Medical Office Database (n = 18.396).

Table 4: Spearman correlation coefficient (r) between dimensions of safety culture and the overall rating of quality issues and patient safety.

Note: aCorrelation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed)

bCorrelation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed)

cCorrelation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed)

Discussion

To our awareness, this is the first research in Greece to assess the safety culture in primary care settings using the MSOPSC instrument, which is specialized to primary healthcare. The domains of safety culture that gained the highest scores were: “Teamwork” (82%), “Patient Care Tracking/Follow-up” (80%), and “Organizational Learning” (80%). In Greece, the operation of basic healthcare facilities in small multidisciplinary teams appears to improve employee cooperation. The high proportion linked with the “Teamwork” dimension, as well as the “Organizational Learning” dimension, reflects this. This is because inter-disciplinary cooperation aids health professionals in understanding shared contextual duties and responsibilities, allowing them to carry out organizational goals, interact with and communicate relevant information, and deliver safe and effective treatment. “Teamwork” emerged as the highest safety culture domain in Yemen (96%) [35] and in Holland (79.2%) [36], where the survey tools MSOPSC and Safety Attitudes Questionnaire were used, respectively.

The “Patient Care Tracking/Follow-up” was another strong area in the present study. This shows that PHU patients in Greece are reminded of their appointments, their commitment to the therapy process is confirmed, and the follow-up with patients who need monitoring is appropriate. This is owing to the fact that primary care electronic systems have been updated in recent years (to include patients’ electronic files and electronic prescriptions); However, much effort has to be done, particularly in the integration of basic and secondary health care. In countries with advanced health information systems, similar findings were observed, such as the U.S. (88%) [37] and Spain (77%) [38], while lower results were reported in countries such as Yemen (52%) [35] and Poland (65%) [39], where primary care services are not supported by an information system. The areas of “Work Pressure and Pace” (46 % ) and “Leadership Support” (62 %) had the least favorable answers. This was mostly due to a longstanding problem in Greece’s healthcare system: a shortage of nurses. According to the World Health Organization [40], Greece has 3.6 nurses per 1000 people, compared to 9.1 in the OECD. Switzerland, Norway, and Denmark all have more than 16 nurses per 1000 people, with Switzerland having the highest ratio (17.4). The absence of leadership support emphasizes the importance of bridging the management-employee communication gap.

Effective leadership must combine the essential qualities of effective communication, cooperation, experience, and flexibility to build a safety culture [41]. It’s worth noting that in comparable research, countries with quite diverse cultures, such as Iran [42] (75 %), Holland [36] (73 %), and Poland [39] had the highest rates in this sector (84 %). The majority of participants thought their basic healthcare facility training was useful. The American respondents fared worse when asked about the availability of on the-job training in terms of new procedures and being asked to conduct activities for which they were not qualified; they fared significantly better when asked about the availability of on-thejob training [43]. In this region, the present study looked to have a 70% approval rating, which was higher than Spain [38] and Yemen [35] with 61% approval ratings, but lower than Poland [39] with 79% approval ratings. Spearman correlation analysis revealed that specific domains of patient safety culture are related to patient safety and quality issues. According to health professional’s views, the quality of health care services is linked with staff training, organizational learning and the standardization of office processes and patient safety to the open, free of blame communication.

There was no significant link between gender and any of the safety culture composites in this study. Women, on the other hand, rated areas like “Patient Care Tracking/Follow-up” and “Overall Perception of Patient Safety and Quality” somewhat higher than males, according to a Polish research [28]. In the domain of “Information Exchange with Other Settings,” men fared better. “Information Exchange with Other Settings,” “Work Pressure and Pace,” “Staff Training,” “Office Processes and Standardization,” “Patient Care Tracking/Follow-up,” “Leadership Support for Patient Safety,” and “Overall Perception of Patient Safety” were all areas, were women in Spain outperformed males. The causes of differences between healthcare providers should be investigated in future study. It should also determine whether there is a relationship between the patient safety culture, patient experiences, overall safety and quality ratings, and adverse event incidence in general practice cooperatives. Furthermore, research on the effects of treatments aiming at enhancing communication or establishing a safer workplace is recommended.

Overall, respondents in this research evaluated healthcare safety and quality as satisfactory in all categories (more than 70%), with the exception of timeliness and efficiency, which were scored positively by 65 percent and 63 percent of respondents, respectively (Table 3). In conclusion favorable patient safety culture evaluations were primarily represented in the areas “Teamwork,” “Patient Care Tracking/Follow-up,” and “Overall Perceptions of Patient Safety” in primary care settings in Greece. Following that, the do-mains “Staff Training,” “Error Communication,” “Office Processes and Standardization,” and “Communication Openness” were followed. There are numerous strengths and limitations to this study that should be considered. The MSOPSC, the most widely used instrument for measuring the safety culture in primary care settings, is one of the strengths. However, there is no literature on the link between patient safety composite scores and respondent characteristics and safety culture outcomes in Greek primary care settings. This is, to our knowledge, the first research in Greece to look at this issue. However, there are a number of limitations to these data that should be addressed. First, the data came from a stratified random selection of units from Greece’s first health region: Attica, rather than a random sample of all PHUs in the country. As a result, a positive selection bias may exist. Second, the findings of this study reflect the perspectives of primary care physicians rather than administrative or technical employees. Finally, no attempt was made to compare the validity of the units’ evidence to other evaluation reports, such as interviews or record reviews [44,45].

Conclusion

This is the first investigation of its kind in Greece, evaluating the patient safety culture in primary care settings. Overall, health professionals have a positive safety culture, however some weak areas need to be addressed in order to improve patient safety. In order to give treatments and address safety concerns, further research into the disparities across professional subcategories is required.

References

- Committee on Diagnostic Error in Health Care; Board on Health Care Services; Institute of Medicine; The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Balogh EP, Miller BT, Ball JR, editors. Improving Diagnosis in Health Care. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US).

- Graber ML, Franklin N, Gordon R (2005) Diagnostic error in internal medicine. Arch Intern Med 165(13):1493-1499.

- Schiff Gordon D, Omar Hasan, Seijeoung Kim, Richard Abrams, Karen Cosby, et al. (2009) Diagnostic error in medicine: analysis of 583 physician reported errors. Archives of internal medicine 169(20): 1881-1887.

- Singh Hardeep (2014) Editorial: Helping health care organizations to define diagnostic errors as missed opportunities in diagnosis. Joint Commission journal on quality and patient safety 40(3): 99-101.

- (2016) Primary health care: Main terminology. World Health Organization.

- Kostopoulou Olga, Brendan C Delaney, Craig W Munro (2008) Diagnostic difficulty and error in primary care--a systematic review. Family practice 25(6): 400-413.

- Singh Hardeep, Dean F Sittig (2015) Setting the record straight on measuring diagnostic errors. Reply to: 'Bad assumptions on primary care diagnostic errors' by Dr Richard Young. BMJ quality & safety 24(5): 345-348.

- Goyder Clare R, Caroline HD Jones, Carl J Heneghan, Matthew J Thompson (2015) Missed opportunities for diagnosis: lessons learned from diagnostic errors in primary care. The British journal of general practice: the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners 65(641): e838-844.

- Panesar Sukhmeet Singh, Debra deSilva, Andrew Carson-Stevens, Kathrin M Cresswell, Sarah Angostora Salvilla, et al. (2016) How safe is primary care? A systematic review. BMJ quality & safety 25(7): 544-553.

- Ely JW, Kaldjian LC, D Alessandro DM (2012) Diagnostic errors in primary care: lessons learned. J Am Board Fam Pract 25(1): 87-97.

- Gandhi Tejal K, Allen Kachalia, Eric J Thomas, Ann Louise Puopolo, Catherine Yoon, et al. (2006) Missed and delayed diagnoses in the ambulatory setting: a study of closed malpractice claims. Annals of internal medicine 145(7): 488-496.

- Silk N (2000) What Went Wrong in 1,000 Negligence Claims. Health Care Risk Report. Medical Protection Society.

- (1999) IOM. To Err Is Human. Building a Safer Health System, International Journal of Public Health.

- (2009) The Council of the European Union. Council Recommendation of 9 June 2009 on patient safety, including the prevention and control of healthcare associated infections. Official Journal of the European Union.

- Slawomirski L, Auraaen A, Klazinga N (2017) THE Economics of Patient Safety. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

- Pettker CM, Thung SF, Raab CA, Donohue KP, Copel JA, et al. (2011) A comprehensive obstetrics patient safety program improves safety climate and culture. In: American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 204(3): 216-226.

- Donnelly LF, Dickerson JM, Goodfriend MA, Muething SE (2009) Improving patient safety: Effects of a safety program on performance and culture in a department of radiology. Am J Roentgenol 193(1): 165-171.

- (1993) HSE ACSNI Human Factors Study Group: Third report - Organising for safety HSE Books 1993. Hse.

- Goh SC, Chan C, Kuziemsky C (2013) Teamwork, organizational learning, patient safety and job outcomes. Int J Health Care Qual Assur 26(5): 420-432.

- McFadden KL, Henagan SC, Gowen CR (2009) The patient safety chain: Transformational leadership’s effect on patient safety culture, initiatives, and outcomes. J Oper Manag 27(5): 390-404.

- Singla AK, Kitch BT, Weissman JS, Campbell EG (2006) Assessing patient safety culture: A review and synthesis of the measurement tools. J Patient Saf 2008: 2.

- Singh H, Giardina TD, Meyer, Forjuoh SN, Reis MD (2013) Types and origins of diagnostic errors in primary care settings. JAMA Intern Med.

- Rosser W, Dovey S, Bordman R, White D, Crighton E (2005) Medical errors in primary care: results of an international study of family practice. Can Fam Physician 51(3): 386-397.

- Koper D, Kamenski G, Flamm M, Böhmdorfera B, Sönnichsena A (2013) Frequency of medication errors in primary care patients with polypharmacy. Fam Pract 30(3): 313-319.

- Parker D, Wensing M, Esmail A, Valderas JM (2015) Measurement tools and process indicators of patient safety culture in primary care. A mixed methods study by the LINNEAUS collaboration on patient safety in primary care. Eur J Gen Pract.

- Feng XQ, Acord L, Cheng YJ, Zeng JH, Song JP (2011) The relationship between management safety commitment and patient safety culture. Int Nurs Rev 21(1): 26-30.

- Ricci Cabello I, Avery AJ, Reeves D, Kadam UT, Valderas JM (2016) Measuring Patient Safety in Primary Care: The Development and Validation of the "Patient Reported Experiences and Outcomes of Safety in Primary Care" (PREOS-PC). Ann Fam Med 14(3): 253-261.

- Smits M, Keizer E, Giesen P, Deilkås ECT, Hofoss D (2018) Patient safety culture in out-of-hours primary care services in the Netherlands: a cross-sectional survey. Scand J Prim Health Care 36(1): 28-35.

- Bondevik GT, Hofoss D, Hansen EH, Deilkås EC (2014) Patient safety culture in Norwegian primary care: a study in out-of-hours casualty clinics and GP practices. Scand J Prim Health Care 32(3):132-138.

- Deilkås ECT, Hofoss D, Hansen EH, Bondevik GT (2019) Variation in staff perceptions of patient safety climate across work sites in Norwegian general practitioner practices and out-of-hour clinics. PLoS One. 14(4): e0214914.

- Zachariadou T, Zannetos S, Pavlakis A (2013) Organizational culture in the primary healthcare setting of Cyprus. BMC Health Serv Res 13: 112.

- Economou C (2010) Greece: Health system review. Health Syst Transit 12(7): 1-16.

- Antonakos I, Souliotis K, Psaltopoulou T, Tountas Y, Papaefstathiou A (2021) Psychometric Properties of the Greek Version of the Medical Office on Patient Safety Culture in Primary Care Settings. Medicines 8(8): 42.

- Eiras, M, Escoval, A, Silva C (2018) Patient Safety Culture in Portuguese Primary Care: Validation of the Portuguese Version of the Medical Office Survey. In Vignettes in Patient Safety-Volume 4 InTech: London, UK, p. 4.

- Dal Pai S, Langendorf TF, Rodrigues MCS, Romero MP, Loro MM (2019) Psychometric validation of a tool that assesses safety culture in Primary Care. ACTA Paul. Enferm 32(6): 642-650.

- Webair HH, Al Assani SS, Al Haddad RH, Al Shaeeb WH (2015) Assessment of patient safety culture in primary care setting, Al-Mukala, Yemen. BMC Fam Pract 16: 136.

- Smits M, Keizer E, Giesen P, Deilkås ECT, Hofoss D (2018) Patient safety culture in out-of-hours primary care services in the Netherlands: A cross-sectional survey. Scand J Prim Health Care 36(1): 28-35.

- Famolaro T, Hare R, Thornton S, Yount ND, Fan L (2020) Surveys on Patient Safety Culture TM (SOPSTM) Medical Office Survey: 2020 User Database Report; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA.

- Romero MP, González RB, Calvo MSR (2017) La cultura de seguridad del paciente en los médicos internos residentes de Medicina Familiar y Comunitaria de Galicia. Aten Prim 49(6): 343-350.

- Raczkiewicz D, Owoc J, Krakowiak J, Rzemek C, Owoc A (2019) Patient safety culture in Polish Primary Healthcare Centers. Int J Qual Health Care 31(8): 60-66.

- (2018) WHO Regional Office for Europe. Health for All database.

- De Brún A, Anjara, S, Cunningham U, Khurshid Z, Macdonald S (2020) The Col-lective Leadership for Safety Culture (Co-Lead) Team Intervention to Promote Teamwork and Patient Safety. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(22): 8673.

- Tabrizchi N, Sedaghat M, Tabrizchi N, Sedaghat M (2012) The first study of patient safety culture in Iranian primary health centers. Acta Medica Iran 50(7): 505-510.

- Hickner J, Smith SA, Yount N, Sorra J (2015) Differing perceptions of safety culture across job roles in the ambulatory setting: Analysis of the AHRQ Medical Office Survey on Patient Safety Culture. BMJ Qual Saf 25(8): 588-594.

- Bower P, Campbell S, Bojke C, Sibbald B (2003) Team structure, team climate and the quality of care in primary care: An ob-servational study. Qual Saf Health Care 12(4): 273-279.

Research Article

Research Article