Abstract

The aim of the present research was to evaluate the plasma concentration of fasting glycemia and muscle mass index. A randomized, double-blind survey was carried out, with data collection carried out over a period of 6 months, in the city of Mossoró, Northeast region of Brazil. Were included elderly female patients with a confirmed diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus. The elderly women were randomly distributed into experimental group 1, for curcumin supplementation, and experimental group 2, for oat bran supplementation and a control group, without supplementation. Regarding nutritional status, the mean values of BMI showed a higher frequency of overweight on elderly women (n=30, 50.0%), followed by (n=25; 41.7%) in the eutrophic state, and less underweight elderly women. (n=5; 8.3%). In the intra-group analysis, when comparing pre and post supplementation values, a significant difference was observed in the glycemia indicator in the group supplemented with curcumin (p-value = 0.005). The oat bran group also showed a significant difference (p-value = 0.008), however, this difference occurred through the increase in glycemia. Also, for the glycemia indicator, a significant difference was observed for the group supplemented with curcumin (p-value = 0.025) when compared to the post-intervention control group. The data suggest that protocol supplementation associated with active elderly women only affected glycemic levels, suggesting that these strategies did not present characteristics of therapeutic use in this population.

Keywords: Elderly; Oat Bran; Curcumin; Glycemy; Nutritional Status

Abbreviations: CVD: Cardiovascular Diseases; EG1: Experimental Group 1, EG2: Experimental Group 2, CG: Control Group

Introduction

The aging process submits the organism to physiological and anatomical changes that influence the health of the elderly, these changes include reduced functional capacity, changes in taste and chewing function, changes in the body’s metabolic processes and changes in body composition [1]. Among the risk factors for disability, chronic diseases, and death, some are related to nutrition, which can lead to type 2 diabetes mellitus, cancer, and cardiovascular diseases (CVD), which are among the main causes of death [2]. Advancing age is the main risk factor for CVD, with a 70% prevalence of CVD in men and women over 60 years of age [3]. By virtue public health problems on the elderly population, non-pharmacological treatments, specifically foods with functional properties, have gained prominence, for presenting an efficient results and low cost [4]. Functional foods are closely related to beneficial effects on the body, including preventing the onset of chronic diseases typical from aging. Thus, nutritional therapy with functional foods must be included daily on clinical practice, with the objective of recovering the nutritional status, appropriate to existing pathologies and eating habits [5]. They are further characterized as those that produce desirable physiological and metabolic effects on health maintenance, in addition to their basic nutritional functions, these effects occur when these foods are consumed along with the usual diet and on a regular basis [6].

Since functional foods have gained greater visibility, especially those foods that provide better living and health conditions for human beings, greater interest has been aroused by industries in replacing synthetic dyes for natural ones. In this context, curcumin appears as an important alternative to the yellow dye. The low toxicity associated with other properties enhances the use of natural dyes as food additives [7,8]. Dietary fiber has also been strongly linked to health benefits. Some randomized studies have shown that the consumption of fiber-rich foods, both insoluble and soluble, act on obesity, CVD and type 2 diabetes as they act by improving glycemic control and contributing positively to weight control [9,10]. The wide use of fiber sources in food is justified by the benefits associated with its consumption [11]. Oats as a great dietary fiber option, has been used for its beneficial effects on health, due to its soluble fiber content, especially β-glucans [12]. The effect of β-glucans in lowering the glycemia has been related to the delay in gastric emptying, so that glucose in the diet is absorbed more slowly and thus the peak glucose level is smoother and the response curve is much smaller benefiting directly the postprandial glycemia of patients with diabetes. These changes reduce the feeling of hunger caused by the rapid decrease in glycemia. Thus, β-glucans can decrease appetite and reduce food intake [13,14]. Therefore, to adapt and prevent dietary inadequacies, with the use of foods with functional properties, it is necessary to include them in nutrition services, encouraging regular consumption in order to offer the elderly protection in the fight against pathologies, with guidelines and efficient practices capable on helping maintaining health during the aging process. Based on the above, what is the relationship of supplementation based on curcumin and oat bran, on fasting glycemia and nutritional status in active elderly women?

Methodology

Sample and Experimental Design

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the State University of Rio Grande do Norte - UERN, under opinion number 3,302,336, and under registration of Rebec RBR-6bp3hk and RBR 75qb7pp. A 6-month, randomized, double-blind clinical study was conducted, the main objective of which was to assess changes in glycemia and nutritional status in elderly women. The selection of the group was a sample of 60 volunteers. Elderly women who were unable to answer the questions due to hearing problems or difficulty in understanding the questions, who were using medications that can change their coagulation characteristics, increasing the risk of bleeding cases, elderly women with a history of allergy to curcumin or other formula components, risks of bile duct obstruction, stomach ulcers and stomach hyperacidity. The information was recorded on the evaluation form. All volunteers did not use curcumin and oat bran and had not participated in any regular physical activity program for at least one year. The technical team consisted of nutritionists and nutrition students, physical education professionals, biochemical pharmacists, nurses and nursing technicians, all involved in data collection. At that time, the elderly answered the initial questionnaires necessary to verify the eligibility criteria, such as the identification form and the Mini- Mental State Examination (MMSE).

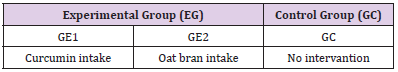

The elderly eligible in the research and who agreed to participate in the research underwent initial assessments, which consisted of applying the Food Consumption Questionnaire, Biochemical and Anthropometric Assessment. The evaluations were carried out pre and post intervention, being T0 for pre intervention and T13 for post intervention. The elderly were randomly, through the Research Randomizer software (version 4.0), in experimental group 1 (EG1), for curcumin supplementation and experimental group 2 (EG2), for oat bran supplementation and control group (CG), without supplementation. A numerical code determined by an auxiliary researcher was created for each participant, which was revealed during the statistical analysis phase. To better control the intake of curcumin and oat bran, the participants received a weekly amount sufficient for 7 days of supplementation. They were instructed to maintain their usual diet, not being the object of study to interfere in the food consumption of the participants (Table 1).

Curcumin Supplementation

Thus, EG1 was offered a total of 1,000mg of curcumin per day as a supplement. Supplementation with curcumin composed of 95% standardized extract of the root of Turmeric Long L. was performed by administering 2 capsules of 500mg of curcumin. The coating of the capsules was dark in color and chlorophyll so that the supplement would not be oxidized and that it would not develop any type of intolerance. The pots with the capsules were separated into codes in the laboratory itself, which manipulated into individual plastic pots, identified with the participant’s name and code.

Bran Supplementation

For EG2, 30g of oat bran per day, obtained from the local market, was offered as a supplement. The oat bran was portioned in plastic bags. measuring 6x23cm. The contents were weighed using a 20Kg Uranus Digital Scale (Pop-S US20/2), the bags with oat bran were portioned and identified with the participant’s name and code. Participants were instructed to ingest the product throughout the day along with food according to their preference.

Fasting Glycemic Analysis

Blood samples were collected after a 12-hour overnight fast, all professionals involved in the collection are qualified to perform the procedure, meeting all the safety requirements of the elderly participants. 5 to 10mL blood samples were collected from the antecubital vein of the participants. Blood collection took place in the clinical analysis laboratory, located in the Professor Vingt-un Rosado Clinical Center, of the Municipality of Mossoró. The days of collection of blood samples were determined by mutual agreement between the researcher, participants and the laboratory, with two collections being performed before and after the intervention. The elderly were called for collection in groups where they were separated in individual and comfortable rooms to maintain data preservation and the integrity of the participants. After collection, a snack was offered to the elderly. Pre and post treatment, fasting glycemia were evaluated. Glycemia classification was made according to the fasting blood glucose value. The values and reference proposed by the Guidelines of the Brazilian Society of Diabetes were used, which suggest plasma reference values ≥100mg/dL [15].

Results

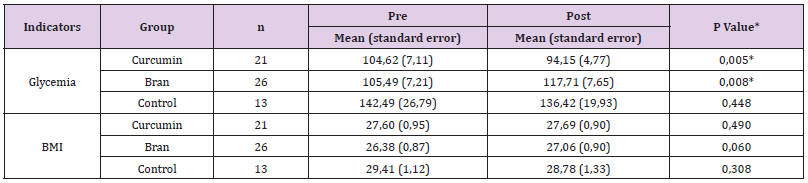

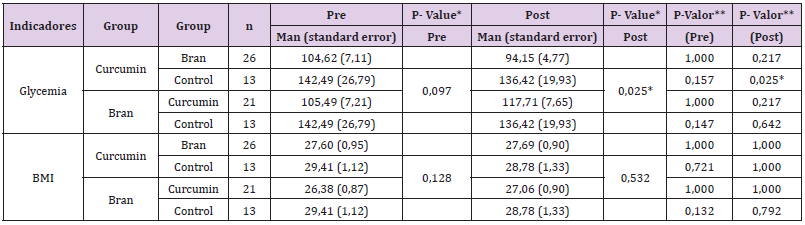

Among the elderly eligible for this research (n = 60), the mean age was 69.73 years (± 5.86), most elderly women considered themselves to be of brown ethnicity (41.7%) or White (36, 7%). With regard to the nutritional status of the study participants, it was possible to see a higher frequency of overweight elderly women (n=30, 50.0%), followed by (n=25; 41.7%) in the eutrophic state, and less frequently elderly women with low weight. (n=5; 8.3%). No side effects were observed during curcumin and oat bran supplementation. With regard to nutritional status, no significant differences were observed when evaluated before and after the intervention and between groups (p-value = 0.532). In the intragroup analysis, when comparing pre and post supplementation values, a significant difference was observed in the glycemia indicator in the group supplemented with curcumin (p-value = 0.005). The oat bran group also showed a significant difference (p-value = 0.008), however, this difference occurred through the increase in blood glucose (Table 2). Also, for the glycemia indicator, a significant difference was observed for the group supplemented with curcumin (p-value = 0.025) when compared to the postintervention control group (Table 3).

Table 2: Mean, standard error and differences in relation to the effect of supplementation in the curcumin and oat bran group and control group (intra-group).

Table 3: Mean, standard error and differences in relation to the effect of supplementation in the curcumin group and oat bran and control group (inter-group).

Note: *ANOVA followed by Post-Hoc of Bonferroni test.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the plasma concentration of fasting glycemia and muscle mass index, which are considered important markers for the maintenance and control of some chronic diseases, such as Diabetes Mellitus, obesity and the like, in active elderly women undergoing a protocol chronic supplementation of curcumin and oat bran strength. It is noteworthy that the dosage of this protocol of dietary supplementation allowed discussions that these interventions may be sufficient to control and maintain glycemic and weight during the aging process, since a difference was only found in the action of curcumin on blood glucose between the experimental groups. Although the present study does not show a reduction on glycemia levels, it is important to emphasize that some elderly women had decompensated glucose, in addition to the fact that the participants’ diet was not controlled, it is known that food consumption is directly related to the health and disease process [15,16]. DM, despite having a lower prevalence when compared to other morbidities, is a highly limiting disease and can cause complications such as blindness, amputations, nephropathies, cardiovascular and encephalic complications, which contribute to damage to functional capacity, autonomy, and quality of life. It is one of the NCDs (non-communicable chronic diseases) that appears as one of the main causes of premature death, due to the increased risk for the development of cardiovascular diseases, which contribute to the deaths of individuals with diabetes [17,18].

Still, dietary fiber has been strongly linked to health benefits. Some randomized studies have shown that the consumption of fiber-rich foods, both insoluble and soluble, act on obesity and type 2 diabetes as they act by improving glycemic control, increasing peripheral insulin sensitivity and reducing exogenous insulin and contributing positively to weight control [9,10]. Soluble fibers show that they are more potent than insoluble fibers in decreasing the presence of risk factors for CVD in animals and humans. In the last two decades there has been a greater interest in β-glucans due to its functional and bioactive properties [10]. Thus, like dietary fiber, the importance of curcumin is known due to the numerous benefits due to its pharmacological activities, including antioxidant, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, antimalarial, antitumor, antiviral, healing, schistosomicidal, hypoglycemic, leishmanicidal, nematicide, neuroprotective, anti-amyloidogenic and immunomodulatory [19]. The main protective effects of curcumin in cardiovascular disorders are to protect against cardiovascular complications in diabetics, as increased oxidative stress has been associated with chronic complications in diabetes, including cardiomyopathy [7]. Interventions aimed at the prevention and control of glycemia can help delay progression to the disease state, well-tolerated and costeffective interventions with multiple mechanisms can provide a better solution for long-term adherence in order to decrease the risk of diabetes [20].

In the present study, it was found that the 12 weeks of oral curcumin supplementation is more efficient in reducing blood glucose, compared to the oat bran group, which, in turn, showed a significant increase when compared before and after intragroup intervention. However, the supplemented elderly women showed better effects than the control group on glucose levels. In the evaluation between the groups, curcumin showed a significant difference compared to the control group, when compared to the post-intervention period. This control may be related to the ability of curcumin to inhibit enzymes that act at the beginning of the process of formation and release of pro-inflammatory enzymes, thus preventing the formation of oxidative stress, acting as an antiinflammatory agent, helping to prevent insulin resistance caused in the inflammatory process, thus being able of providing a reduction on glycemia in overweight, obese or type 2 diabetes people [7,21]. Interventions aimed at the prevention and control of blood glucose can help delay progression to the disease state, well-tolerated and cost-effective interventions with multiple mechanisms can provide a better solution for long-term adherence in order to decrease the risk of diabetes [20]. Also, with the findings of this study, in the inter-group evaluation, no significant differences were observed in the lipid profile indicators or in body composition, demonstrating a similarity in the general health status during the intervention period. In this work, it was also verified a higher frequency of overweight elderly women, followed by eutrophy, the possible explanations for the greater chances of middle-aged and elderly women to be overweight is the greater accumulation of visceral fat, food intake, longer life expectancy and alterations due to menopause. At the same time, underweight had a lower frequency in accordance with the nutritional transition of the Brazilian population [22].

No significant differences were observed for body composition in any of the groups evaluated, both before and after the intervention, when compared between groups. Among the various ways to assess the nutritional status of this population, BMI appears as one of the most used indicators, due to the ease of data acquisition and low cost. It is noteworthy that other factors such as lifestyle, income, education and food consumption are shown to be related to a higher frequency of overweight in elderly women [23]. The present study has limitations that must be considered. There were no evaluations of other biochemical markers, lack of control over food consumption, which is a possible factor that may have influenced the responses of the analyzed biochemical markers. Based on these parameters, it is possible to see the importance that nutrition has in the health-disease process of the elderly population and the relevance of nutritional monitoring and analysis of food intake in order to early detect nutritional deficiencies and/or disorders, contributing to improve the quality of elderly life. The implementation of health promotion measures, through dietary changes and the practice of physical exercise, as well as programs and public policies can improve the quality of life of elderly women. After analyzing the data, it is concluded that the protocol supplementation associated with active elderly women only affected the glycemia levels in elderly women, suggesting that these strategies did not present characteristics of therapeutic use in this population.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no economic interest or conflict of interest.

References

- Vitolo MR (2014) Nutrition: from pregnancy to aging 2. Rio de Janeiro Rubio, pp. 1- 576.

- (2002) WHO. Innovative care for chronic conditions: building blocks for actions: global report.

- Santos Parker JR, Strahler TR, Bassett CJ, Bispham NZ, Chonchol MB, et al. (2017) Curcumin supplementation improves vascular endothelial function in healthy middle-aged and older adults by increasing nitric oxide bioavailability and reducing oxidative stress. Aging (Albany NY) 9(1): 187-208.

- Hasler CM (2002) Functional foods: benefits, concerns and challenges-a position paper from the American Council on Science and Health. The Journal of nutrition 132(12): 3772-3781.

- Busnello FM (2007) Nutritional aspects in the aging process. São Paulo Atheneu, pp. 292.

- Barleta AD, Noronha VC (2017) Functional food: a new therapeutic approach for dyslipidemias as prevention of atherosclerotic disease. notebooks unifoa 2: 100-120.

- Rosa CDOB, Oliveira T (2009) Evaluation of the effect of natural compounds–curcumin and hesperidin on induced hyperlipidemia in rabbits. [Dissertation]. Viçosa: Universidade Federal de Viç

- DiSilvestro RA, Joseph E, Bomser J (2012) Diverse Effects of a Low Dose Supplement of Lipidated Curcumin in Healthy Middle Aged People. Faseb Journal 11: 79.

- Fujita AH, Figueroa MO (2003) Proximate composition and b-glucan content in cereals and derivatives. Food Science and Technology 23: 116-120.

- Nörnberg FR (2014) Oat bran and native and oxidized ß-glucan concentrates: effect on endocrine and metabolic parameters in rats fed a hypercholesterolemic diet. [Dissertation]. Pelotas: UFPel.

- Philippi ST, Colucci ACA (2018) Nutrition and gastronomy. Barueri: Manole, pp. 512.

- Barroso SG, Das Dores SMC, Azeredo VB (2015) Effects of functional foods consumption on the lipid profile and nutritional status of elderly. Int J Cardiovasc Sci 28(5): 400-408.

- Mira GS, Graf H, Cândido LMB (2009) food with an emphasis on beta-glucans in the treatment of diabetes. Brazilian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 45: 11-20.

- Da Silva ALV, Silva EdPO, De Fontes JM, Nunes TC, Pontes EDS, et al. (2018) Oat Beta Glucan (Avena Sativa) and Its Relationship to Diabetes Mellitus. International Journal of Nutrology 11: 212.

- (2015) Guidelines of the Brazilian Society of Diabetes: 2014-2015/Brazilian Society of Diabetes; [organization José Egidio Paulo de Oliveira, Sérgio Vencio]. São Paulo: AC Pharmacist.

- Moratoya, EE (2013) Changes in the pattern of food consumption in Brazil and in the world. Agricultural Policy Goiás 5: 72-84.

- Schaan BD, Harzheim E, Gus I (2004) Cardiac risk profile in diabetes mellitus and impaired fasting glucose. Rev Public Health 38(4): 529-536.

- (2004) World Health Organization/International Diabetes Federation. Action now against diabetes: an initiative of the world health organization and the international diabetes federation. Genebra: world health organization/international diabetes federation.

- Panahi Y, Kianpour P, Mohtashami R, Jafari R, Simental Mendía LE, et al. (2016) Curcumin lowers serum lipids and uric acid in subjects with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of cardiovascular pharmacology 68(3): 223-229.

- Thota RN, Acharya SH, Garg ML (2019) Curcumin and/or omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids supplementation reduces insulin resistance and blood lipids in individuals with high risk of type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled trial. Lipids in health and disease 18(1): 31-31.

- Zhang Dw, Fu M, Gao SH, Liu JL (2013) Curcumin and diabetes: a systematic review. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine.

- Batista Filho M, Rissin A (2003) Nutritional transition in Brazil: regional and temporal trends. Public health notebooks 19(1): S181-S91.

- Acuña K, Cruz T (2004) Evaluation of the nutritional status of adults and elderly people and the nutritional status of the Brazilian population. Brazilian Archives of Endocrinology & Metabolism 48: 345-361.

Research Article

Research Article