Abstract

Objective: Nowadays the conservative treatment in case of solid organ injury in abdominal trauma is the procedure of choice, regardless of the injury degree. Our objective is to describe our abdominal trauma protocol in case of a solid organ injury and present a case of a pediatric patient with liver organ injury after an abdominal trauma.

Case Report: A 13-year-old-patient was transfer to our center with a liver injury after blunting abdominal trauma. Demographic data, trauma mechanism, organ, associated lesions, examination made at diagnosis and follow-up, type of treatment, success rate of treatment, complications during admission and after discharge were collected.

Conclusion: The gold standard for the initial treatment of abdominal trauma with solid organ injury, regardless of the degree of involvement, is the conservative treatment.

Keywords: Abdominal Trauma; Liver Injury; Conservative Management; Pediatrics

Abbreviations: SOI: Solid Organ Injury; APSA: American Pediatric Surgical Association; BAT: Blunt Abdominal Trauma; CT: Computed Tomography; GGT: Gamma-Glutamyl Transferase; GOT: Glutamic-Oxaloacetic Transaminase; GPT: Glutamic-Pyruvic Transaminase; PICU: Pediatric Intensive Care Unit

Introduction

Pediatric trauma is the main cause of mortality and morbidity in patients under 1 years of age, being a cause of disability greater than the rest of childhood illnesses. The abdominal trauma represents around 8 to 15% of all injuries, being the third cause of mortality in these patients. The overall real survival of the traumatized patient is greater than 90% [1]. The current standard treatment in the hemodynamically stable pediatric patient with solid organ injury (SOI) and regardless of the degree of injury is conservative (except pancreatic lesions with complete section of the excretory duct and renal lesions with excretory pathway involvement). There are only descriptions in the literature of management guidelines for patients with abdominal trauma of severe disease hemodynamically stable and without associated lesions [2,3]. However, these guidelines are not applicable to patients with the presence of one or more associated lesions, such as brain trauma. The aim of our study is to describe a polytraumatized pediatric patient with blunt liver injury grade V.

Initial Treatment Protocol

Conservative treatment is the treatment of choice in our patients. We consider angioembolization as part of the conservative treatment. Surgical treatment was reserved for those patients with initial hemodynamic instability refractory to conservative treatment. The success of conservative treatment is defined as the absence of surgical indication in the first 72 hours after admission.

Complementary Explorations Protocol

The performance of an abdominal computed tomography is performed by routine in abdominal trauma. The degree of traumatisms was established following the classification of the AAST (The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma) (Table 1) [1].

Inpatient Follow-Up Protocol

Clinical examination and laboratory tests are mandatory. The process of analysis and monitoring of arterial blood gasses and blood tests are an essential part of diagnosing and managing of the patients specially during the first 48 hours. The standard radiological control recommendation by the American Pediatric Surgical Association (APSA) is summarized in the guidelines for the use of resources in patients with blunt abdominal trauma (BAT) with SOI (Table 2) [4,5]. However, in our center we apply this protocol partially adapted to the characteristics of our hospital setting, performing ultrasound controls during the hospital admission of SOI every 24-48 hours in grades II-V.

Outpatient Follow-Up

Ambulatory controls (one control at least) are carried out without performing radiological studies by routine, except for clinical suspicion or persistence of radiological lesions in previous controls, indicating ultrasound control as radiological test of choice until resolution of them monthly.

Case Report

A 13-year-old-patient was transfer to our center with a BAT. The patient was emergency lifted by helicopter after a skiing accident. A full head to toe physical exam was performed in the emergency department: in the abdominal exam, tenderness to palpation of the right flank was described; abdominal distension and bruise were not objectified. Lacerations in the upper limbs and abrasions in the lower limbs without bony malformations were described. A computed tomography (CT) scan was performed getting detailed images of hypodense areas (parenchymal disruption) in hepatic segments V-VIII without active hemorrhage (Figure 1). According to the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma liver injury scale, the injury was suggestive of grade V liver laceration. Laboratory work-up shown hemoglobin of 13.8 g/dL, white blood cell count of 7030 × 103 per microliter (μL) (4.5–14.5 × 103/μL), a C-reactive protein level of 7.8 mg/L (3–5 mg/L), a total bilirubin level of 13 μmol/L (0–17 μmol/L) , an amylase leve of 51 U/L (1- 100 u/L), an alkaline phosphatase (ALP) level of 61 units per liter (U/L) (35–110 U/L), gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) levels of 297 U/L (1–48 U/L), glutamic-pyruvic transaminase (GPT) levels of 324 U/L (1–31 U/L), and glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase (GOT) levels of 246 U/L (1–31 U/L).

Figure 1: Computed Tomography scan showing hypodense areas (parenchymal disruption) in hepatic segments V-VIII.

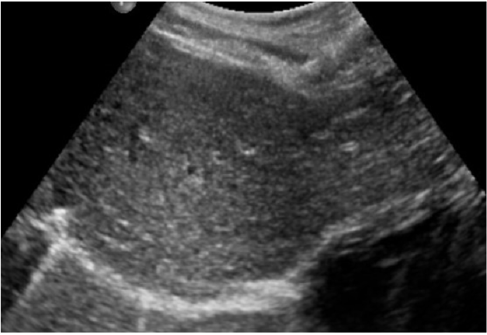

Due to the hemodynamic stability, the patient was admitted into the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) for the first 72 hours. Clinical examination and laboratory tests were performed daily without anemizing secondary to liver bleeding (hemoglobin level of 13.8 g/dL on day 7). Ultrasound controls were performed each 48 hours. Three days after admission, the patient had a good clinical status, enteral nutrition was restarted, and the abdominal pain had also disappeared. The laboratory test showed total bilirubin (B) level of 7 μg/L, gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) levels of 48 U/L, glutamic-pyruvic transaminase (GPT) levels of 121 U/L and glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase (GOT) levels of 41 U/L. The patient was discharged on day 7 with a good clinical status. Two weeks later, a clinical control in the outpatient department revealed no clinical or laboratory abnormalities and an abdominal ultrasound revealed a practically remission of the previous abnormal findings. During outpatient follow-up, the liver injury was resolved after 1 month of ultrasound controls (Figure 2). No complications were diagnosed after 3 years of follow up and the patient remains asymptomatic.

Discussion

Currently, conservative treatment of traumatic SOI in children is firmly established as the treatment of choice, with a high success rate (up to 95% in most series) [5-7]. Once conservative treatment has been established as the first option in hemodynamically stable patients with SOI, is necessary to standardize the performance algorithms and establish non-surgical treatment protocols based on clinical evidence. For this purpose, the Trauma Committee of the APSA attempted to establish an evidence-based clinical action guide for the treatment of hemodynamically stable closed liver and spleen injuries [4,8,9]. The requirement of radiological follow-up after a successful conservative treatment in these patients has been debated for almost 30 years. There are no references in the literature about radiological correlation of the lesions, the period that takes to solve them and the starting of physical activity in those patients. Similarly, there are no randomized controlled trials on the optimal use of radiological resources in the pediatric population in such patients [10-14]. Conventional abdominal ultrasound is considered the best choice for the follow-up of these patients, although there is no consensus about the time and impact on the evolution. On the other hand, some series report the absence of complications in the follow-up of these patients, reaching figures of up to 87% without requiring radiological studies, regardless of the degree of injury [11,12,15,16].

We describe in our patient a success of the conservative treatment without embolization and surgery requirements. No complications were described during the follow-up period in the ultrasound controls until the liver injury resolution after one month. New prospective studies are necessary (level of evidence I-II) that emphasize the ambulatory follow-up of patients with SOI in the pediatric population and the requirement for radiological tests to achieve a more efficient resources management, without decreasing the efficacy of the therapeutic management. The management of pediatric abdominal trauma (including liver trauma) should be multidisciplinary including pediatric surgeons, interventional radiologists, and emergency and PICU physicians [17].

Conclusion

The gold standard for the initial treatment of abdominal trauma with SOI, regardless of the degree of involvement, is the conservative treatment. The computed tomography is the radiological examination of choice in cases of hemodynamic stability. Although the percentage of complications is low, inpatient and outpatient follow-up with radiological examinations, specifically abdominal ultrasound, is currently necessary for the diagnosis and followup of complications in the pediatric patients. To start of contact sports (football, wrestling, hockey, lacrosse, scaling, etc.) must be determined individually by the pediatric surgeon. The proposed guidelines for return to activity without restrictions include “normal” activities for age.

References

- (2013) In: Nance ML (Eds.)., American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma. NTDB Pediatric Report 2013. American College of Surgeons.

- A B van As, Alastair J W Millar (2017) Management of paediatric liver trauma. Pediatr Surg Int 33(4): 445-453.

- David A Partrick, Denis D Bensard (1999) Nonoperative management of solid organ injuries in children results in decreased blood utilization. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 34(11): 1695-1699.

- Stylianos S (2002) Compliance with Evidence-Based Guidelines in Children with Isolated Spleen or Liver Injury: A Prospective Study. New York Journal of Pediatric Surgery 37(3): 453-456.

- Nance M, Holmes HJ (2006) Timeline to operative intervention for solid organ injuries in children. J Trauma 61: 1389-1392.

- O’Neill JA (2000) Advances in the management of pediatric trauma. Am J Surg 180: 365-369.

- Holmes HJ, Wiebe DJ, Monica Tataria, Kelly D Mattix, David P Mooney, et al. (2005) The failure of nonoperative management in pediatric solid organ injury: A multi-institutional experience. The journal of trauma injury, infection, and children care 59(6): 1309-1313.

- Stylianos S (2000) Evidence-Based Guidelines for Resource Utilization in Children with Isolated Spleen or Liver Injury. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 35(2): 164-169.

- Mullins R, Trunkey D (2006) Variation in treatment of pediatric spleen injury at trauma centers versus nontrauma centers. J Amer Coll Surg 203(2): 263.

- Stylianos S (2005) Outcomes from pediatric solid organ injury: role of standardized care guidelines. Current Opinion in Pediatrics 17(3): 402-406.

- Upadhyaya P (2003) Conservative management of splenic trauma. Pediatr Surg Int 19: 617-627.

- Tinkoff G, Esposito TJ, Reed J, Kilgo P, Fildes J, et al. (2008) American Association for the Surgery of Trauma Organ Injury Scale I: spleen, liver, and kidney, validation based on the National Trauma Data Bank. J Am Coll Surg 207(5): 646-655.

- Pranikoff T, Hirschl RB, Schlesinger AE, T Z Polley, A G Coran, et al. (1994) Resolution of splenic injury after nonoperative management. J Pediatr Surg 29: 1366-1369.

- Lynch JM, Meza MP, Newman B, M J Gardner, C T Albanese, et al. (1997) Computed tomography grade of splenic injury is predictive of the time required for radiographic healing. J Pediatr Surg 32: 1093-1096.

- Mizzi A, Shabani A, Watt A (2002) The role of follow-up in paedriatic blunt abdominal trauma. Clinical radiology 57: 908-912.

- McGrew PR, Chestovich PJ, Fisher JD, Kuhls DA, Fraser DR, et al. (2018) Implementation of a CT scan practice guideline for pediatric trauma patients reduces unnecessary scans without impacting outcomes. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 85(3): 451-458.

- Coccolini F, Coimbra R, Ordonez C, Kluger Y, Vega F, et al. (2020) Liver trauma: WSES 2020 guidelines. World J Emerg Surg 15(1): 24.

Case Report

Case Report