Abstract

Introduction: Amblyopia represents the main cause of visual impairment in the developmental age, with a prevalence in preschool children between 1.5 and 4.0%. Preschool visual screening is an evidence-based practice that allows for an early diagnosis of amblyopia and consequently an early treatment that can allow recovery, even total, of visual function. This study reports on the evaluation of the final outcome of visual screening in three consecutive cohorts of children born in the province of Trento and subjected to visual screening at the age of 4, then verifying the quality of vision after 2/3 years.

Material and Methods: The subjects identified as amblyopic among children undergoing preschool visual screening at 4 years (second year of kindergarten), in the years 2012-2014, were taken into consideration. These subjects, registered in the screening archive, were followed retrospectively up to three years after the date of the screening to verify, through the Hospital Information System, whether or not they had carried out an eye examination, verifying the acuity vision values achieved for the right eye and the left eye respectively. The data relating to the treatment carried out were also recovered. The difference between the post-treatment and pre-treatment visit acuity values was assessed by the student’s T test for the statistical significance of the differences. The assessment of the quality of vision at screening and at the follow-up assessment was also expressed in LOGMar. The significance of the differences between the proportions under comparison (gender, citizenship, residence area) was tested with the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test, as needed. Proportions are provided by 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

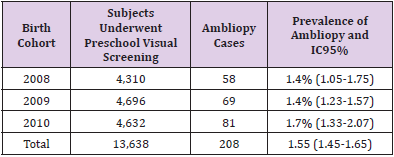

Results: In the years 2012-2014, 13,638 children underwent preschool visual screening, with an average coverage of 96%. Children classified as amblyopic were 208, for an average prevalence of 1.5%. Astigmatism affects 80% of cases. Data on outcome evaluation were recovered at 6/7 years of age in 178 subjects (85.6% of the series). Corrective lenses were prescribed in all 178 cases evaluated. One subject underwent surgical treatment for congenital cataracts. An exclusive occlusive therapy was performed in 171 subjects (96%), in 7 cases the filters were used exclusively, given the impracticability of the occlusive treatment. In a further 9 cases, filters were used after recognition of poor compliance with the occlusive treatment. The average level of visual acuity at the evaluation of 6/7 years passes from 5.3 to 9 tenths for the right eye and from 4.7 to 9 tenths for the left eye. There is a statistically significant increase in the average values of visual acuity and isoacuity. Foreign children reach levels of visual acuity lower than in Italians. There were no differences in outcomes in relation to gender and residence area of the cases. The visual quality achieved is affected by the basic defect present.

Discussion: Various aspects, internal and external to the Health Service, do not allow a full evaluation of the case history. The study indicates that there are no inequalities in access to follow-up after setting up the treatment. The outcomes are quite satisfactory, in line with international studies and without significant differences in relation to the gender, citizenship and residence of children. The outcome assessment activity should also be more systematic to allow for a timely reorientation of the operational approaches of the screening program.

Keywords: Preschool Visual Screening; Amblyopia; Outcome Assessment

Introduction

Amblyopia represents the main cause of visual impairment in the developmental age. It is a condition of reduced mono or bilateral visual acuity that also occurs independently of an organic cause. It is due to inadequate visual stimulation during the plastic period of development of the visual system. Literature data indicate a prevalence of amblyopia in preschool age between 1.5 and 4.0%. Its most common causes are represented by strabismus and refractive errors [1]. In developing countries, amblyopia is the second most common cause of functional vision impairment in children [2]. Preschool visual screening allows for an early diagnosis of amblyopia and consequently an early treatment which, if implemented within 6 years, can allow a recovery, even total, of the visual function. This aspect is very important for the overall development of the child and his / her abilities / possibilities for learning and social integration [3,4].

Given the need to treat the basic conditions (any congenital cataracts, refractive errors, etc.), the classic treatment essentially rests on two approaches: the eye bandage that has better visual acuity (for a few hours a day depending on the severity of the amblyopia and / or the tolerance of the treatment), in order to work the amblyopic eye or, alternatively or in addition to the use of penalties such as filters on the lenses, less coercive treatment than bandages, but which does not preclude the possibility of binocular collaboration. The duration of treatment depends on the extent of amblyopia and compliance with therapy and should be modulated on the results of periodic checks to be carried out in the followup after the start of treatment [5-9]. This screening represents an evidence-based practice, as recently reconfirmed by the US Preventive Service Task Force, a body of the American Federal Agency for Research and Quality of Care.

The latest update, released in 2017, confirms the adequacy of screening between the ages of 3 and 5, while robust evidence of efficacy for screening in children under the age of three is not yet available [10]. The data on screening are also satisfactory in terms of cost-effectiveness [11]. Preschool visual screening, in the second year of kindergarten, has been active in the province of Trento (540,000 inhabitants in north-east Italy) since the second half of the 1980s and currently covers the entire province with long-established organizational and operational criteria. The organizational aspects, operating procedures and coverage of the screening in place in the province of Trento were the subject of previous work [12]. This study reports on the evaluation of the final outcome of orthotic screening in three consecutive cohorts of children undergoing screening and diagnosed with amblyopia at the age of 4, considering the quality of vision verified after 3 years.

Material and Methods

The subjects identified as amblyopic, born in the years 2008- 2010 and subjected to pre-school visual screening at 4 years (second year of kindergarten), that is in the years 2012-2014, were taken into consideration. These subjects, registered in the screening archive, were followed retrospectively up to three years after the date of screening, then at the age of 6-7, to verify whether or not they had undergone a control eye examination, verifying the visual acuity values achieved for the right eye and the left eye respectively. The data relating to the treatment carried out were also recovered. The recovery of follow-up data was carried out by accessing the SIO (Hospital Information System), which is a sort of electronic repository where all the health services enjoyed by resident and non-resident users in the province of Trento are recorded. The proportion of subjects who received a post-screening eye assessment was assessed, identifying the duration of the follow-up, and the age of the child at the assessment, distinguishing by gender, residence and citizenship.

The level of visual acuity achieved was assessed, for both eyes, with reference to the level of visual acuity at the time of screening and therefore before treatment. The difference between posttreatment and pre-treatment visit acuity values was assessed for the statistical significance of the differences with the student T test. The assessment of the quality of vision at screening and at the follow-up assessment was also expressed in LOGMar (Logarithm of the Minimum Angle of Resolution). It is a criterion for estimating visual acuity developed at the National Vision Research Institute of Australia in 1976, and it should provide more accurate estimates than those of other charts [13,14]. The significance of the differences between the proportions in comparison was tested by the chisquared test or Fisher’s exact test, as needed. The proportions are provided by 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

Results

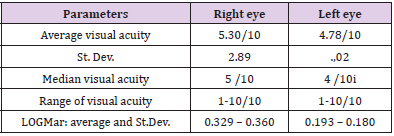

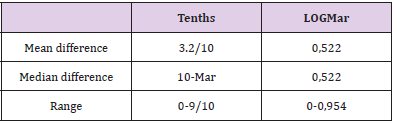

In the years 2012-2014, 13,638 children underwent preschool visual screening, with an average coverage (net of subjects already in care, of those absent from school and not recovered subsequently and of those who did not receive parental consent) equal to 96%. In the period under study, an average of two children per year were identified as having amblyopia within the first three years of life, therefore before the invitation to preschool screening. Children classified as amblyopic were 208 at the end of the various stages of screening, for an average prevalence for the period of 1.5% (Table 1). Bilateral cases of amblyopia were 10 (4.8%) and severe forms equal 8 cases (3.8%). Males represent 51.9% of the series (108 subjects) and children of foreign citizenship 13.9% (29 subjects). The visual acuity level for the two eyes at screening, for the 208 cases diagnosed with amblyopia, is shown in (Table 2). The difference in visual acuity between the two eyes is shown in (Table 3).

Table 1:Province of Trento. Subjects underwent preschool visual screening and ambliopy prevalence (CI 95%). By birth cohort. Period 2012-2014.

Table 2:Province of Trento. Visual acuity level in ambliopic cases identified by screening Period 2012-14.

Table 3:Province of Trento. Difference in visual acuity between the two eyes in ambliopic cases identified by screening. Period 2012-14.

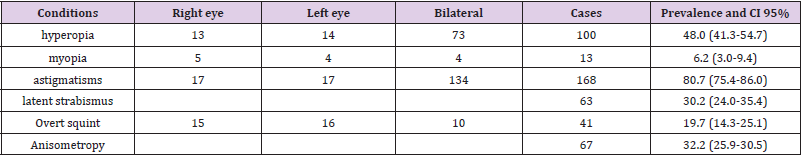

The subdivision according to the refractive defects identified is shown in Table 4, from which it emerges that the most frequent condition is astigmatism which affects 80% of cases. In 203 cases (97.6%) corrective lenses were prescribed, at the end of the screening, to ascertain an amblyopia condition by the ophthalmologist. As regards the follow-up and the remote outcome of the screening, data on the outcome assessment, at 6/7 years of age, were recovered for 178 subjects (85.6%); for 82.4% of males, 89% of females; 93.1% of foreigners and 84.3% of Italians. The data of 30 cases are not recoverable, equal to 14.4% of the cases. Of the latter cases, 4 were also related to subjects who moved out of the province after the completion of the screening and therefore not assessable for the effectiveness of the treatment. The actual proportion of those assessed remotely is therefore equal to 87.4%, of the subjects actually assessable.

Table 4:Province of Trento. Frequency and CI 95% of refractive defects identified by screening in amblyopy cases. Period 2012-14.

The proportion of subjects for whom the information was retrieved did not vary in a statistically significant way, in relation to the residence area (urban or rural). The average follow-up from the ophthalmologist’s diagnosis and the start of therapy was 1 year and 8 months, with a range ranging from 1 year and 3 months to 3 years. The average age of the subjects assessed for the outcome is 6.4 years, the median value is 6.2 years, with a range from 5.6 years to 7.8 years. Corrective lenses were prescribed in all 178 cases evaluated. One subject underwent surgical treatment for congenital cataracts. An exclusive occlusive therapy was performed in 171 subjects out of 178 evaluated (96%), in 7 cases the filters were used exclusively, given the impracticability of the occlusive treatment. In a further 9 cases, filters were used after the recognition of poor compliance with the occlusive treatment.

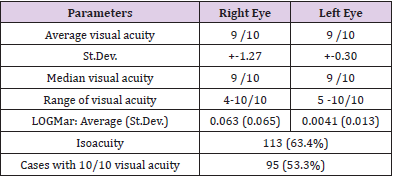

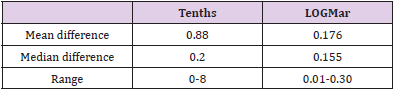

The median duration of treatment was estimated to be 26 weeks with a range of 16 to 54 weeks. The average level of visual acuity at the evaluation of 6/7 years passes, for the right eye from 5.3/10 to 9/10 and for the left eye from 4.7 to 9/10 (Table 5). In the forms of severe/bilateral amblyopia, visual acuity values at 6-7 years, are on average lower than in the other cases. Comparing the mean values of visual acuity for the two eyes, a statistically significant improvement (p <0.01) is noted at 6-7 years compared to the date of screening (Table 6). A condition of isoacuity affects 113 subjects at 6-7 years, equal to 63.4%. Comparing the proportion of children with isoacuity at screening and at evaluation at 6-7 years, there is a statistically significant difference (p <0.001). The 10/10 of visual acuity, a parameter that is not required to define the resolution of amblyopia, is reached by 53.3% of the children evaluated, respectively by 56.2% of Italian children and by 37% of foreign children.

Table 6:Province of Trento. Difference in visual acuity between the two eyes in ambliopic cases evaluated at 6-7 years.

However, the difference between citizenship is not statistically significant, nor is the difference in relation to gender. The 10/10 of visual acuity is achieved by 54.4% of astigmatics, 44.3% of hyperopic, 28.0% of cross-eyed and 10% of myopic. A condition of isoacuity is reached at 6/7 years of age by 113 children (63.4%), respectively by 64.9% of Italian children and by 55.5% of foreign children, without however a statistically significant difference in relation to citizenship, as well as in relation to gender. As in the case of the 10/10 visual acuity parameter, the achievement of isoacuity is also influenced by the type of associated refractive defect, considering that this condition is reached in 66.2% of astigmatics, in 55.6% of hyperopic, in 36.0% of cross-eyed and 20.0% of myopic. The data relating to myopic people is also emphasized by the low number of cases: 10 evaluated at 6 years compared to the total of 13 identified at screening. The data relating to subjects with overt squint is the only statistically significant with respect to the mean (p <0.001). Finally, in only three cases the visual acuity in the amblyopic eye is equal to 4 tenths (> 0.30 LOGMar).

Discussion

A long-term outcome evaluation is the only reliable way to evaluate the effectiveness of a screening. This is also valid for preschool visual screening where the goal is to improve the levels of visual acuity to support the full development of the child and his or her learning and social integration possibilities. Our study represents the first outcome assessment of the preschool visual screening program in the province of Trento, more than thirty years after its launch. A shorter periodicity of evaluation would be recommended in order to understand in a short time whether the program works or not. The evaluation activity is however onerous in terms of time expenditure and requires the availability of an information system that allows the useful data to be available. The evaluation would also require, to be more appropriate, to have data on the child’s educational impact and for this reason it should consider a time well beyond the 6-7 years threshold.

Anyway, SIO, in our experience, appears to be a useful information tool even if it could be supplemented by information that can be provided by the family pediatricians. These professionals follow children from birth through puberty so they are ideally placed to provide prospective data. Their involvement in this type of activity should in any case be regulated and appropriately encouraged. An alternative way could be to contact directly the family even though this approach may not provide all the data of interest [11,15,16]. Defining any preferential ways for the specialist assessment of screened subjects could in any case be advantageous, also for the purpose of retrieving information for outcome assessments [11]. Referring to the current available information flows we were able to recover data relating to a post-screening evaluation for 87.4% of cases (about 9 cases out of 10). An incomplete recovery of the follow-up data could be related, rather than to an actual lack of adherence to the therapeutic path, to the failure to register remote assessments in the SIO, or to access to private eye clinics, which implies an inability to access the evaluation of the treatment given that the services in the private sector are not registered in the SIO.

This may explain the fact that foreign children are more likely to be assessed remotely than Italians, as the former tend more frequently to access public facilities than the seconds. On the basis of the available data, we report no differences in access to the 6-7th year outcome assessment in relation to gender, citizenship and residence area. Even in the presence of incomplete evaluation data, a picture of homogeneity and equity of the treatment path emerges without the presence of apparent barriers, which have already been reported in the literature [17-19]. However, precise data relating to compliance with therapy are not available, an aspect of great importance for the purposes of the efficacy of the treatment and which is influenced by the level of awareness of parents on the importance of regularity of periodic checks, post screening [11,20- 22]. Compliance with treatment can be guaranteed on the basis of optimal collaboration between the family and the care team: orthoptic / eye services and family pediatrician.

A qualitative study, designed ad hoc, would have been indicated for the assessment of compliance [11]. From our study we can hypothesize that at least 16 children (9.0%) may have had problems accepting the occlusive treatment. We can hypothesize greater compliance problems in children with a foreign mother, considering that the effectiveness achieved in foreigners is lower than in Italians even if the difference is not statistically significant. Problems with access to services and compliance with treatment in the foreign population have also been reported in the literature [23,24]. Finally, we found no differences in relation to the mother’s level of education, an aspect indicated as a possible barrier to access to treatment in other studies [25]. Taking into account the information limits mentioned above, we can believe that the pre-school visual screening program of the province of Trento is effective. A clear increase in visual acuity emerges, both for individuals and for all the subjects evaluated.

The differences between the visual acuity values at 6-7 years and the screening values appear statistically significant, in line with what is reported in the literature [26-32], despite the difference in programs and procedures. There are no relevant associations between the results at 6-7 years and the degree of amblyopia and/or the refractive defect as identified at screening even if in astigmatics the improvement in visual performance seems better. In conclusion, the remote results of the provincial preschool visual screening are completely satisfactory and in line with the findings of the international literature. The coverage of the 6-year evaluation is satisfactory even if a centralization of the activity would be appropriate, in order to facilitate and optimize the outcome evaluation. It would be advisable to design a multidimensional and multiprofessional evaluation system that allows a timely return of the outcome of the program.

References

- Bradfield YS (2013) Identification and treatment of amblyopia. Am Fam Physician 87(5): 348-352.

- Gilbert CE, Ellwein LB (2008) Prevalence and causes of functional low vision in school-age children: results from standardized population surveys in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 49(3): 877-881.

- Rahi J, Logan S, Timms C, Russell Eggitt I, Taylor D (2002) Risk, causes, and outcomes of visual impairment after loss of vision in the non-amblyopic eye: a population-based study. Lancet 360(9333): 597-602.

- Davidson S, Quinn GE (2011) The impact of pediatric vision disorders in adulthood. Pediatrics 127(2): 334-339.

- Stewart CE, Fielder AR, Stephens DA, Moseley MJ (2002) Design of the Monitored Occlusion Treatment of Amblyopia Study (MOTAS). Br J Ophthalmol 86(8): 915-919.

- Stewart CE, Moseley MJ, Stephens DA, Fielder AR (2004) Treatment dose–response in amblyopia therapy: The Monitored Occlusion Treatment of Amblyopia Study (MOTAS). Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 45(9): 3048-3054.

- Cotter SA, Edwards AR, Wallace DK, Beck RW, Arnold RW, et al. (2006) Treatment of anisometropic amblyopia in children with refractive correction. Ophthalmology 113(6): 895-903.

- (2006) Royal_College_of_Ophthalmologists. Guidelines for the Management of Amblyopia.

- Shotton K, Powell C, Voros G, Hatt SR (2008) Interventions for unilateral refractive amblyopia. Cochrane database of systematic reviews 8(4): CD005137.

- Jonas DE, Amick HR, Wallace IF, Feltner C, Vander Schaaf EB, et al. (2017) Vision Screening in Children Aged 6 Months to 5 Years: Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 318(9): 845-858.

- Carlton J, Karnon J, Czoski-Murray C, Smith KJ, Marr J (2008) The clinical effectiveness and cost- effectiveness of screening programmes for amblyopia and strabismus in children up to the age of 4-5 years: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Ass 12(25): xi-194.

- Piffer S, Bombarda L, Trettel C (2016) Screening ortottico prescolare. Oftalmologia Sociale 3: 37-44.

- Bailey IL, Lovie JE (1976) New design principles for visual acuity letter charts. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 53 (11): 740-745.

- Grosvenor T (2007) Primary care Optometry. St. Louis, Missouri: ELSEVIER, pp. 174-175.

- Ethan D, Basch CE (2008) Promoting healthy vision in students: Progress and challenges in policy,

- programs, and research. Journal of School Health d August 78(8): 411-416.

- Donahue SP, Baker CN (2006) Procedures for the evaluation of the visual system by pediatricians. Pediatrics 137(1).

- Williams S, Wajda BN, Alvi R, Mc Cauley C, Martinez Helfman S, et al. (2013) The challenges to ophthalmologic follow-up care in atrisk pediatric populations. J AAPOS 17: 140-143.

- Yawn BP, Kurland M, Butterfield L, Johnson B (1998) Barriers to seeking care following school vision screening in Rochester, Minnesota. J Sch Health 68(8): 319-324.

- Kemper AR, Uren RL, Clark SJ (2006) Barriers to follow-up eye care after preschool vision screening in the primary care setting: findings from a pilot study. J AAPOS 10: 476-478.

- Dixon Woods M, Awan M, Gottlob I (2006) Why is compliance with occlusion therapy for amblyopia so hard? A qualitative study. Arch Dis Child 91(6): 491-494.

- Wallace MP, Stewart CE, Moseley MJ, Stephens DA, Fielder AR (2013) Compliance with occlusion therapy for childhood amblyopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 54(9): 6158-6166.

- Su Z, Marvin EK, Wang BQ, Van Zyl T, Elia MD, et al. (2013) Identifying barriers to follow-up eye care for children after failed vision screening in a primary care setting. J AAPOS 17(4): 385-390.

- Tarczy Hornoch K, Cotter SA, Borchert M (2013) Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study Group. Prevalence and causes of visual impairment in Asian and non-Hispanic white preschool children: Multi-ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study. Ophthalmology 120(6): 1220-1226.

- Ying GS, Maguire MG, Cyert LA, Elise Ciner, Graham E Quinn, et al. (2014) Vision in Preschoolers (VIP) Study Group. Prevalence of Vision disorders by racial and ethnic group among children participating in head start. Ophthalmology 121(3): 630-660.

- Holte L, Walker E, Oleson J, Hua Ou, J Bruce Tomblin, et al. (2012) Factors Influencing Follow-up to Newborn Hearing Screening for Infants who are Hard-of-Hearing. Am J Audiol 21(2): 163-174.

- Holmes JM, Kraker RT, Beck RW, Birch EE, Cotter SA, et al. (2003) A randomized trial of prescribed patching regimens for treatment of severe amblyopia in children. Ophthalmology 110(11): 2075-2087.

- Repka MX, Beck RW, Holmes JM, Birch EE, Chandler DL, et al. (2003) A randomized trial of patching regimens for treatment of moderate amblyopia in children. Arch Ophthalmol 121(5): 603-611.

- Anstice N, Spink J, Abdul Rahman A (2012) Review of preschool vision screening referrals in South Auckland, New Zealand. Clin Exp Optom 95(4): 442-448.

- De Koning HJ, Groenewoud JH, Lantau VK, Tjiam AM, Hoogeveen WC, et al. (2013) Effectiveness of screening for amblyopia and other eye disorders in a prospective birth cohort study. J Med Screen 20(2): 66-72.

- Schmucker C, Grosselfinger R, Riemsma R (2009) Effectiveness of screening preschool children for

- amblyopia: a systematic review. BMC Ophthalmology 9(3): 1-12.

- Khambhiphant B, Srisuwanwattana W (2012) A one-year review of amblyopia treatment for literate patients at King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital. J Med Assoc Thai 95(10): 1302-1305.

- Holmes Lazar (2011) PEDIG. Effect of age on response to amblyopia treatment in children

- Arch Ophthalmol 129(11): 1451-1457.

Research Article

Research Article