Abstract

Generally, 0.5% of all cases of stroke present as cerebral venous thrombosis. Although the COVID-19 infection mainly affects the respiratory system, some neurological disorders, such as stroke, have been reported during active infection but not during the convalescent phase. In this study, we present the case of a 35-year-old nurse with no past medical history, who presented to the emergency room with acute global aphasia seven weeks after being diagnosed with COVID-19. Computed tomography confirmed cranial venous thrombosis in her left sigmoid and transverse sinus. The patient was started on oral anti-coagulants, and her symptoms disappeared in 12 hours. Although it is strongly suggested that the patient’s cerebral venous thrombosis was due to her use of oral contraceptives, it is important not to neglect the influence of COVID-19. Hence, further testing and research should be conducted in the field of hyper-coagulability for COVID-19 survivors, even if they are young and have no pre-existing medical conditions.

Keywords: Cerebrovascular Stroke; Venous Thrombosis; Global Aphasia; COVID-19

Abbreviations: CT: Computed Tomography; CTA: Computed Tomography Angiography; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Introduction

Cerebral vascular stroke is considered one of the leading causes of death and also one of the reasons for long-term disability [1]. It usually results from arterial occlusion or haemorrhage. Generally, 0.5% of all stroke cases present as cerebral venous thrombosis. The most affected veins are the superior sagittal and transverse sinus, and the symptoms are generally related to the venous structure involved [2]. Although COVID-19 mainly affects the respiratory system, some neurological disorders have been reported. These include brain inflammation, loss of the ability to smell and taste, Guillain–Barré syndrome and stroke [3]. However, these complications are usually observed during the acute phase of infection, not 35 days after the initial infection, as a thromboembolic event [4].

Case Report

This study was performed in line with ethical standards following the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from the patient before participation. At the time of the study, the patient was a 35-year-old medical nurse working at a general practitioner’s office. She was not a smoker; she had no preexisting medical conditions and no known allergies and she was on oral contraceptives. She was married, had two teenage children and was at the time attending the faculty to become a registered nurse. She also used to work 40 hours weekly. On 22 December 2020, the patient presented with headache and fever. She was tested for COVID-19, and the result was positive. Therefore, she stayed in quarantine for 14 days, during which she experienced mild headaches, fever and loss of the ability to smell and taste. After the quarantine, she returned to her job and school, had no residual symptoms and was not complaining of any specific symptoms. She was also not prescribed any additional medication, but she continued to use her oral contraceptives. On 6 February 2021, she woke up with a mild headache and tried to use her mobile phone but could not understand the words written on the screen.

She, however, carried on with her daily routine, but in the evening, she felt very tired, disoriented and unable to speak. Her husband noticed that she was not able to form words and that the words she was saying do not make sense. He immediately called for medical assistance. When the emergency medicine doctor arrived at their house, she could not speak, nor could she recognize any of her family members. Her blood pressure, pulse, oxygen saturation and blood glucose levels were normal. An electrocardiogram was also performed but was normal. Therefore, she was asked to stand up and walk to the ambulance, which she did without any problems. Even after the ambulance arrived at the hospital, she exhibited no significant changes in her status. A neurological exam was performed, which revealed no neurological deficits except for her inability to speak and read. Her blood tests came back negative, and no electrolytical disbalance or signs of intoxication were observed. Her D-dimer levels were also normal.

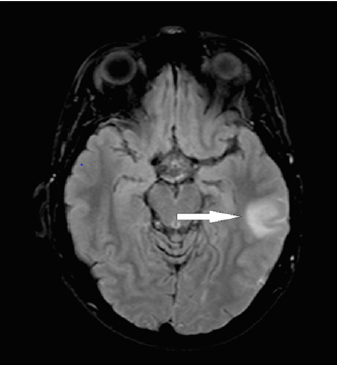

However, given her observable global aphasia, a Computed Tomography (CT) scan was performed on her head and computed tomography angiography (CTA) was performed on the intra-cranial blood vessels. A hypodense area measuring 2 cm in diameter was observed on the left temporo-subcortical side, which is normally observed after a fresh stroke (Figure 1). However, no pathology of the intra-cranial artery system was observed, except for a lightly coloured left sigmoid and transverse sinus, which is very suspicious of cranial venous thrombosis. The patient was immediately started on oral anti-coagulants, and her oral contraceptives were stopped. On the next day, she felt less fatigued, her headache subsided, and she was able to speak, understand, write and read normally. After one week, brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed, revealing the same results as those of the CT scan performed on admission (Figure 2). Therefore, she was discharged from the hospital, continued her course of oral anti-coagulants and was scheduled for a check-up with a neurologist after three months. She was then included in a study on genetical testing, and several tests were performed to exclude thrombophilia. Although she is currently still waiting for the results, her prognosis is promising, and we assume that she will be able to return to her workplace and school after six months.

Discussion

Cerebral vascular stroke is one of the leading causes of death and also one of the reasons for long-term disability [1]. It is usually caused by arterial occlusion or haemorrhage. Generally, 0.5% of all stroke cases present as cerebral venous thrombosis. This is a rare form of stroke that usually affects young adults and children and is three times more likely in females than in males [2]. Venous thrombosis usually affects the lower extremities and rarely involves other venous districts. Rare cases of venous thrombosis, such as cerebral venous thrombosis, account for 4% of all cases hospitalised for venous thrombosis [5]. The incidence rate of this disease is estimated to be four cases per 1,000,000 adults and seven cases per 1,000,000 children annually [6]. The most affected veins are the superior sagittal and transverse sinus, and the symptoms are mainly related to the venous structure involved. These include headaches, papilledema, seizures, focal neurological deficits and altered consciousness. The symptoms evolve slowly over two days up to a month, and they rarely resemble those of arterial stroke.

The mortality rate associated with this disease is 50%, with those who survive rarely having any consequences left. The risk factors associated with this disease include oral contraceptives and thrombophilia [7]. Even though it is strongly suggested that the patient’s cerebral venous thrombosis was due to her use of oral contraceptives, it is important not to neglect the influence of COVID-19 infection. Although COVID-19 infection mainly affects the respiratory system, some neurological disorders have been reported. These include brain inflammation, loss of the ability to smell and taste, Guillain–Barré syndrome and stroke [3]. However, these complications are usually observed during the acute phase of infection, not 35 days after the initial infection, as a thromboembolic event [4]. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome or long COVID is a term used to describe persistent symptoms that may be related to infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus (the virus responsible for COVID-19 infection), as a result of residual inflammation during the convalescent phase as well as organ damage, which are mainly due to hospitalisation, social isolation and pre-existing health conditions [8].

The symptoms are usually mild and include shortness of breath, fatigue, lymphopenia, high blood ferritin and D-dimer levels, headache, memory disorders and cognitive deterioration. These symptoms may persist for up to 10-14 weeks after the onset of the disease. It is possible that our patient was suffering from this post-acute COVID-19 syndrome, which made her more susceptible to thromboembolic complications. Therefore, further testing and research should be conducted in the field of hyper-coagulability for COVID-19 survivors, even if they are young and have no preexisting medical conditions. The limitation of this study is that we were unable to find any studies on the relationship between oral contraceptives and COVID-19 infection in patients with post- COVID-19 stroke. It should also be pointed out that there is no diagnostic tool or treatment currently available to prevent these kinds of complications for COVID-19 survivors.

References

- Martinelli I, Passamonti SM, Rossi E, De Stefano V (2012) Cerebral sinus-venous thrombosis. Intern Emerg Med 3: S221-S225.

- Behrouzi R, Punter M (2018) Diagnosis and management of cerebral venous thrombosis [published correction appears in Clin Med (Lond). Clin Med (Lond) 18(1): 75-79.

- Medicherla, Shadi MD, Ishida, Koto MD, Torres, et al. (2020) Cerebral Venous Sinus Thrombosis in the COVID-19 Pandemic, Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology: December 4(4): 457-462.

- Priftis K, Algeri L, Villella S, Spada MS (2020) COVID-19 presenting with agraphia and conduction aphasia in a patient with left-hemisphere ischemic stroke. Neurol Sci 41(12): 3381-3384.

- Martinelli I, Bucciarelli P, Passamonti SM, Battaglioli T, Previtali E, et al. (2010) Long-term evaluation of the risk of recurrence after cerebral sinus-venous thrombosis. Circulation 121(25): 2740-2746.

- Capecchi M, Abbattista M, Martinelli I (2018) Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost 16(10): 1918-1931.

- Dakay K, Cooper J, Bloomfield J (2021) Cerebral Venous Sinus Thrombosis in COVID-19 Infection: A Case Series and Review of The Literature. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 30(1): 105434.

- Moreno Pérez O, Merino E, Leon Ramirez JM, Vicente Boix, Joan Gil, et al. (2021) Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Incidence and risk factors: A Mediterranean cohort study. J Infect 82(3): 378-383.

Case Report

Case Report