Abstract

Introduction: Prematurity exposes newborns to infectious complications due to their immature immune system. Mast cells seem to have a central place in their defenses considering their predominant location in the bronchial and digestive epithelia.

Objective: Evaluate mast cell activity in preterm infants using an assay of serum tryptase level (STL), a specific protease of mast cell activation.

Material and methods: A case-control study compared STL of preterm infants to full-term infants. We also evaluated STL kinetics in preterm infants, with and without infectious complications.

Results: 51 patients were included per group. STL were homogenous in full-term infants and variable in preterm infants. Mean STL was lower (p = 0.02) in preterm infants (5.02μg/L) than in full-term infants (6.17μg/L) after excluding 4 preterm infants presenting a confounding factor (prolonged premature rupture of membranes). This result reflects a quantitative deficit in immunity effector cells of preterm infants. Preterm infants at risk of enterocolitis (NEC) had a higher basal tryptase level (7.02μg/L) than the others (4.84μg/L) (p = 0.04). Prolonged premature rupture of membranes in preterm babies was associated with a higher STL: 12.37μg/L versus 5.06μg/L (p <0.0001).

Conclusion: The prognosis of the most vulnerable preterm infants seems to be dependent on unregulated mast cell hyperactivity leading to a deleterious inflammatory response in different epithelia. STL assay can be used for screening these at-risk patients. Additional data are needed to establish threshold values.

Keywords: Preterm Infant; Immunity; Mast Cells; Tryptase; Enterocolitis

Abbreviations: STL: Serum Tryptase Level; NEC: Necrotizing Enterocolitis; TLR: Toll-Like Receptors; PROM: Premature Rupture of Membranes; BPD: Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia

Introduction

Prematurity affects 6.6 % of births in France [1,2]. It is the first cause of neonatal mortality [3]. It induces a high rate of neonatal morbidity correlated with gestational age [4]. Preterm infants are vulnerable, and often incapable of surviving extrauterine life. Invasive procedures are required to save these babies subsequently putting them at higher risk for infections due to their immature immune systems [5]. Mast cell, known as “Allergy effector cell” [6,7], is an innate immunity cell found in tissue interfaces. In the first line of defense, it orchestrates the communication between the innate immunity cells and activates the adaptive immunity [8]. It regulates many immune processes [9-11]. Mast cell activation has two pathways: the known IgE pathway and the Toll-Like Receptors (TLR) pathway [12]. TLR are membrane receptors that recognize conserved sequences directly. These pathways lead to mast cell mediators’ secretion including tryptase. Independent IgE mast cell activation pathways are not associated with degranulation but with secretion [13].

Tryptase is a mast-cell specific serine protease: more than 99% of tryptase originates from mast cells. It is a pro-inflammatory agent. [14] Total tryptase assay is performed routinely. It is a standardized technique [15,16]. We believe that mast cell activity has a central place in the immunity of premature newborns. Prematurity induces more vulnerability to infection due to a quantitative and qualitative deficit in immune cells [17-20]. An immature immune system puts mast cells in the front line of the body’s defenses. Tryptase is predominantly located in the bronchial and digestive tissues. Interestingly, tryptase is known to play a role in the immune phenomena of these organs [21-26]. Therefore, mast cell activation could be involved in premature babies’ pathologies like necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) and bronchial dysplasia.

Our objective was to evaluate mast cell activity in preterm

babies by answering 4 questions:

a) Do preterm infants have a higher serum tryptase level than

full-term infants?

b) What is the kinetics of basal serum tryptase levels in preterm

infants?

c) What is the evolution of its concentration during infectious

complications such as necrotizing enterocolitis?

d) Does an “at-risk” population stand out?

Material and Methods

We performed a monocentric prospective study at Reims University Hospital. We evaluated serum tryptase level (STL) in preterm versus full-term infants (to bring an answer to question 1). We evaluated the evolution of STL in preterm infants (question 2) and its evolution in infectious complications (question 3). We then tried to draw conclusions from our data to enhance the possibilities of screening babies at-risk of developing NEC (question 4). Children born before 37 WA were included as “cases”. Children born after 37 WA following were included as “controls”. For preterm babies, a tryptase assay was done for every routine blood analysis and in case of complications. For full-term babies, it was done at 3 days of life. Tryptase assay requires 1mL of extra blood. Total tryptase concentration (alpha and beta) was determined by a fluoroenzymatic technique (FEIA- fluoro enzyme immunoassay) using a PLC “UNICAP 250” (Phadia, Thermofisher Scientific).

Data collection was reported on an observational chart. We collected general data for each patient such as: sex, date of birth, term, weight, height, twin or single pregnancy, complications during pregnancy and/or birth, cause of prematurity. For each tryptase sampling we collected the following data: term, if the sampling was carried out during an infectious (NEC, intraventricular hemorrhage, severe broncho-dysplasia, central catheter sepsis) or non- infectious event, tryptase concentration, blood count and CRP.

Statistical Analysis

Data description included means and standard deviations for quantitative variables, as well as numbers and percentages for qualitative variables. Biological results (tryptase concentration) were compared by using a Student-t test. Evolutions of the different biological assays were studied via correlations and the Pearson’s test. Threshold of significance was set at 0.05. We obtained an ethics agreement. Biomedical research and bioethics laws were respected (Eastern CPP and ANSM). This study was funded by “Comité des Amis de l’American Memorial Hospital”.

Results

Description of the Population

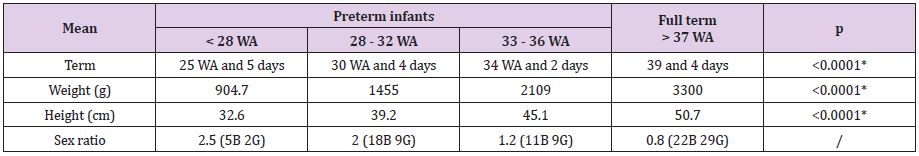

51 babies were included in each group from December 2015 to August 2017. Preterm infants were frailer than in national data (Table 1a). Causes, complications of prematurity and mortality data were like national data (Table 1b). During analysis, we noticed that four patients (two pairs of twins) had a particularly high STL respective STL of 24μg/L, 20.7μg/L, 20.7μg/L (21, 8μg/L then 19.6μg/L) and 18.1μg/L. We sought to understand why these patients had such high values. Apart from the first result (24μg/L) which is the highest and which corresponds to an infectious event (neonatal Candida infection), others are not associated with infectious events. We see that this rate decreases with time (with reference to the third patient who had two dosages).

Table 1a: Term, weight, height and sex.

WA: weeks of amenorrhea G girls - B boys.

According to the National Perinatal Survey (ENP) study in 2010, mean term in preterm infants was 33 WA and 3 days and mean

weight was 2292g.

Table 1b: Causes, complications of prematurity and mortality.

IUGR: Intra uterine growth retardation.

Common points of these four patients are twinning and birth following a prolonged premature rupture of membranes (PROM). In a same pair of twins, STL is very similar according to adults’ literature data, but twinning is not associated with higher STL based on adults’ data and on results of the other preterm twins in our study. Once these 4 patients were excluded, average STL for multiple pregnancies was lower than for single pregnancies (5μg/L versus 5.13μg/L respectively p = 0.86). The assessment of impact of birth after prolonged PROM was significant (even after these 4 patients were excluded). This factor may partly explain high STL in these 4 patients. Nevertheless, tryptase values of these 4 preterm infants stand out clearly from those of other preterm infants born after prolonged PROM. They must have another confounding factor unknown to us and that cannot be explained with our current data (higher anaphylactic risk in these patients?). We therefore decided to exclude these four patients from our analysis.

Serum Tryptase Level “Preterm Infants” versus “Full Term Infants”

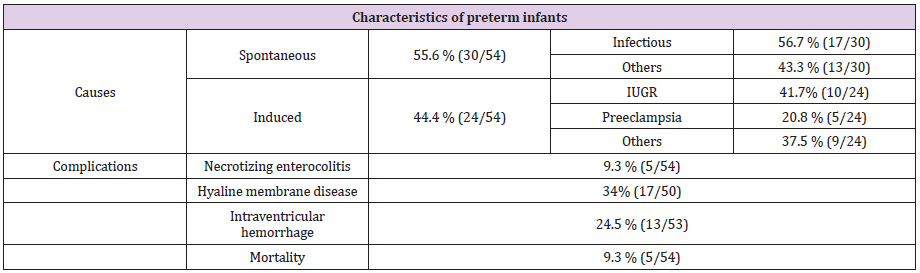

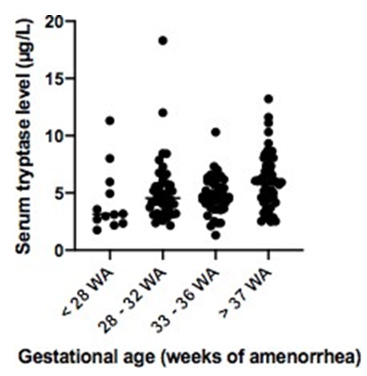

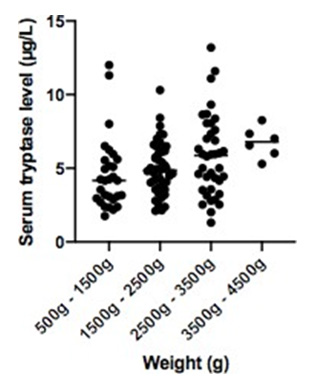

STL were homogenous in full-term infants and variable in preterm infants. Mean STL was lower in preterm infants (5.03μg/L) than in full-term infants (6.17μg/L) (p = 0.02) after excluding the 4 preterm infants presenting a confounding factor. In terms of gestational age, we had these results: 4.33μg/L, 5.23μg/L and 4.79μg/L in respectively < 28 WA, 28-32 WA and 33-36 WA, and 6.05μg/L in > 37 WA (p = 0.03) (Table 2a). STL increases with weight after excluding the 4 preterm infants presenting a confounding factor: 4.6 μg/L, 5.01μg/L, 5.85μg/L and 6.75μg/L in respectively 500g-1500g, 1500g-2500g, 2500g-3500g and 3500g- 4500g (p = 0.05) (Table 2b).

Table 2a: Serum tryptase levels according to gestational age in “preterm infants” versus “full term infants” after excluding 4 preterm infants presenting confounding factor.

Table 2b: Serum tryptase levels according to weight in preterm infants and full-term infants after excluding 4 preterm infants presenting confounding factor.

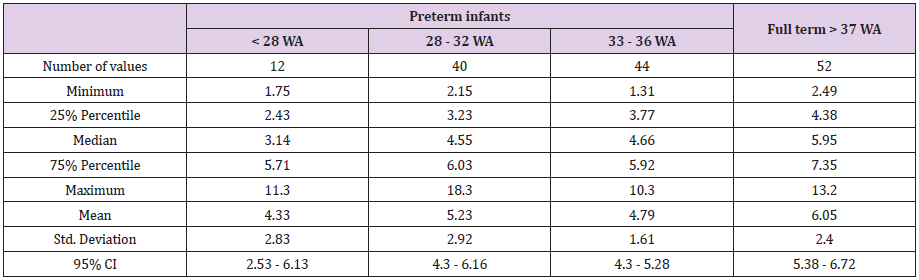

Serum Tryptase Level During Infectious Events: Average STL obtained during infectious events was slightly higher than in the absence of any infectious event: 4.92μg/L during infections versus 4.77μg/L in absence of infection (p = 0.8) (after excluding the 4 preterm infants presenting a confounding factor) (Table 3a). These infectious events were very heterogeneous. Regardless, there were high tryptase concentrations in maternal-fetal or neonatal infections: chorioamnionitis (11.3μg/L). Enterocolitis increases tryptase rates (6.59μg/L and 5.61μg/L): 1 to 2 points above the previous rate. Others: Catheter infections or gastric sample infections were associated with lower rates (≤ 5μg/L). The type of infectious event had an impact on tryptase concentration.

Serum Tryptase Level According to Time Elapsed Between

Rupture of Membranes and Birth in Premature Infants

(

Table 3a: Serum tryptase level during infectious events after excluding 4 preterm infants presenting confounding factor.

distribution of serum tryptase level in case of infectious event versus without infectious events (after excluding 4 preterm infants presenting confounding factor).

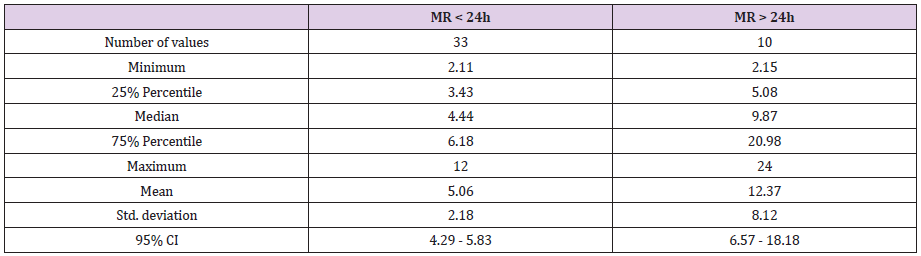

Table 3b: Serum tryptase level according to time elapsed between rupture of membranes and birth in premature infants (

distribution of serum tryptase level in preterm infants born after less than 24 hours of membranes rupture versus preterm infants born after more than 24 hours of membranes rupture.

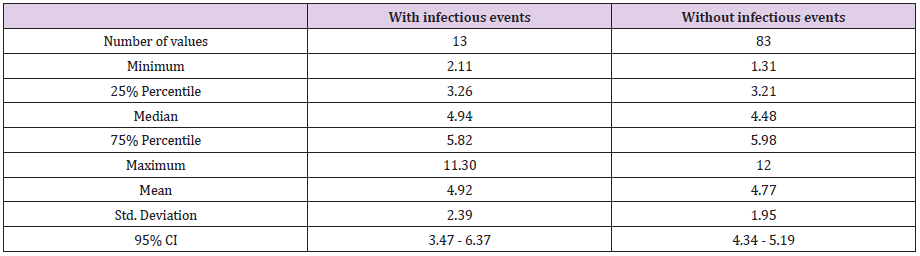

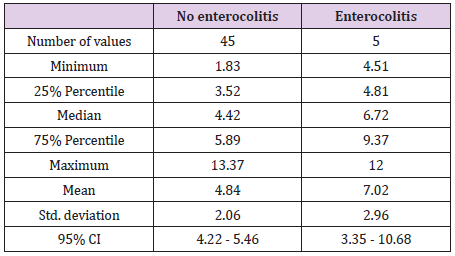

Basal Serum Tryptase Level in Preterm Infants with Enterocolitis versus other Preterm Infants

Preterm infants at risk of NEC had a higher basal STL than the others. After excluding the 4 preterm infants presenting confounding factor, this result was statistically significant: 7.02μg/L versus 4.84μg/L (p = 0.04) (Table 4). Five patients presented with NEC: three stage 1 (6,65μg/L, 4,51μg/L and 6,72μg/L) and two died (12μg/L and 5,1μg/L).

Table 4: Basal serum tryptase level in preterm infants with enterocolitis versus other preterm infants after excluding 4 preterm infants presenting confounding factor.

Discussion

Children born prematurely have physiological specificities that can lead to significant clinical repercussions on their development. They are at risk for different types of complications (respiratory, digestive, neurological, infectious and metabolic complications) during the neonatal period, secondary to a difficult adaptation to extra-uterine life due to their immature organism. Particularly, their immature immune system has reactive specificities that may play a deleterious role during an acute inflammatory process. Mast cell, a cell of innate immunity that is therefore in first line of defense and very present in interface tissues such as intestine and lung epithelia, seems particularly relevant in preterm babies with no previous contact with extrauterine life. Its activity is easy to evaluate thanks to the clinically controlled dosage of one of its specific mediators the tryptase. Tryptase is a serine specific mast cell protease (> 99%) [14]. It is a pro-inflammatory agent that activates the PAR 2 receptor. In turn the PAR 2 receptor activates respiratory homeostasis, gastrointestinal smooth muscle activity and intestinal transport, contraction and vascular relaxation, coagulation [27,28].

Basal concentration is stable in each individual person, but there is “interindividual disparities”. Elevation of total tryptase level can reflect two things: [14]

a. Elevation of immature forms (monomers α and β) due to

elevation of mast cells population in the body.

b. Or elevation of mature form (β tetramers) due to mast cell

activation and degranulation.

Hence the interest of the sequential dosing: at acute episode

and 24 to 48 hours after. Interpretation must be done considering

basal concentration:

a. If elevation is due to degranulation, only the acute dosage will

be increased.

b. If elevation is due to mast cell pool elevation, both

concentrations (at acute and 48h later) will remain high. It

reflects the basal concentration.

Ideally it would have been perfect to perform after each dosage

a systematic control 48 hours later to clarify the clinical situation of

these infants. But that would have meant adding an extra sample.

This was not planned in the protocol. In addition, samples should

be limited in preterm babies who have less blood volume.

Tryptase normal values established by Thermo-Fisher in adulthood are less than 11.4μg/L (median 3.8μg/L, with 95% control values <11.4μg/L) [29]. These normal values are increased in children during the first three months of life (child between 10 days of life and one month: median of 6.1μg/L [30]. From 6 months of life, values become like adult values and remain stable over the life course of an individual (median of 3.15μg/L between 11 and 12 months of life) [30]. It seems to increase again in persons over 80 years (median 6.6μg/L) [31]. Values for babies under 10 days of life and preterm infants remain unknown. Our study suggests that serum tryptase level is lower and more variable in preterm infants (5.03μg/L) than in full-term infants (6.17μg/L) (p = 0.02). This reflects a quantitative deficit in immunity effector cells of preterm infants [32]. For example, we note that preterm babies who died for other reasons than enterocolitis were born extremely premature (25 WA and 4 days, 28 WA and 1 day and 24 WA and 2 days) with mean low concentrations at 3.28μg/L, 3.19μg/L and 2.34μg/L. Their immune system is much more immature with fewer mast cells (thus lower tryptase); it is unable to react to external aggressions. This could explain their vulnerability and death rate.

Tryptase level was slightly higher during infectious events: 4.92μg/L during infectious events versus 4.77μg/L in the absence of infections (p = 0.8). These results are not significant. This is due to the presence of many biases. First, in this calculation, tryptase level interindividual variability could not be considered, because of the small number of doses per patient. Furthermore, tryptase variations are minimal ones. They require a larger cohort to allow for some significance. Second, these infectious events were very heterogeneous. However, we could notice, that there was a higher concentration in case of maternal-fetal or neonatal infection and positive change in enterocolitis.

Prolonged premature rupture of membranes (PROM) is associated with a higher level of neonatal tryptase: 12.37μg/L versus 5.06μg/L (p <0.0001). “Lag phase” duration has an impact in the occurrence of neonatal infections: risk of neonatal infections is higher when babies are born premature and if they were born 24 hours after membrane rupture [33,34]. High neonatal tryptase levels after prolonged premature rupture of membranes reflect the induction of a “fetal inflammatory response syndrome” FIRS [35]. This syndrome is associated with neurological [36] and respiratory [37,38] neonatal complications in the weakest premature babies. Indeed, among our 10 patients with maternal-fetal infection, those who were hypotrophic with high tryptase levels had respiratory and neurological complications. Hypotrophy is a prognostic factor for complications in case of activation of FIRS generated by premature rupture of membranes. It could be interesting to assess if children who benefit from antenatal corticosteroid treatment had a lower concentration of neonatal tryptase.

In case of anaphylactic risk, basal individual tryptase concentration seemed to be higher [39-41]. Hence the relevance of evaluating basal concentration of children who presented with enterocolitis, to know if it could reflect a susceptibility to develop enterocolitis. Interestingly, preterm infants at risk of enterocolitis had higher basal tryptase levels than others. Mast cells are lower in premature infants; so, this suggests an elevation of tryptase basal secretion in these patients. The increase in mast cell activity seems to be implicated in the occurrence of enterocolitis: a deleterious enteral mast cell activation not suppressed during postnatal bacterial intestinal colonization. On the other hand, elevation of the tryptase level at 10 days of life in full term babies could be related to this postnatal bacterial colonization (occurrence of enterocolitis at day 10 of life in preterm babies) [30].

Due to prematurity, mast cell has a central place in “physiological” immune response while waiting for immune system maturation. Prematurity sensitizes mast cells to stimuli by independent IgE pathway (TLR) [42]. This exposes preterm newborns to a deleterious inflammatory response on the epithelial barriers. Pro-inflammatory factors like tryptase are secreted. Tryptase targets are in the digestive and respiratory systems by PAR2 receptor [27,28]. That is why these sites are vulnerable. This deleterious inflammatory response is not repressed by the weakest babies because of a lack of protective mediators, such as IL-10 and TGFβ which are present in breast milk [43-53].

In the intestinal mucosa, the triad “prematurity - bacterial toxins - hypoxia” (predisposing factors for ulcerative necrotizing enterocolitis [54]) increases TLR4 expression in the mucosa. The interaction of bacteria and enterocytes that over expressed TLR4 induce intestinal disorders due to greater apoptosis and lesser repair. This leads to intestinal barrier failures and an increase of its permeability. This allows pathogenic bacteria translocation [55]. Consequently, this presence of bacteria activates an excessive and inappropriate inflammatory response by mast cells leading to inflammation and necrosis [56-60] (Figure 1a-1b). TLR 4 is also present in mast cells [61]. Mast cell activation by TLR only uses the MyD88 dependent pathway and leads to pro-inflammatory cytokine production by the NFκB [62]. Enterocolitis inflammation pathway also involves the MyD88 pathway by NFκB [55,63,64]. A therapeutic proposal would be to inhibit the TLR4 pathway in mouse model (ex: Epidermal Growth Factor EGF [55]). TLR4 is also present in the mast cells found in the respiratory system [65]. Tryptase and mast cells play a major role in hyperoxia-induced lung injury [66-68] and inflammation as well as hyperpermeability of respiratory epithelium [69-71]. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) is associated with overactivation of mast cell activity; there is an association between BPD and TLR4 gene’s polymorphisms in premature infants [72-74]. It would be interesting to evaluate tryptase concentration in patients with BPD.

Figure 1a: Associated with Table 2a: distribution of serum tryptase level according to gestational age in preterm infants versus serum tryptase level in full term infants (after excluding 4 preterm infants presenting confounding factor).

Figure 1b: Associated with Table 2b: distribution of serum tryptase level according to weight in preterm and fullterm infants (after excluding 4 preterm infants presenting confounding factor).

Conclusion

We underline the relevance of a systematic dosage. First, via the measurement of basal tryptase serum level concentrations in preterm infants to highlight those at risk of complications like enterocolitis. Second, the dosage in preterm babies born after prolonged rupture of membranes to identify preterm infants at risk of respiratory and neurological complications. The prognosis of the most vulnerable preterm newborns seems to be dependent on unregulated mast cell hyperactivity (activated by TLR receptors) leading to a deleterious inflammatory response in different epithelia. Additional data are needed to establish threshold values.

Acknowledgment

Thank you to the American Memorial Committee that funded this project. Their generosity made this project and others possible.

Conflict of Interest

We declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Blondel B, Supernant K, Du Mazaubrun C, Bréart G, pour la Coordination nationale des Enquêtes Nationales Périnatales (2006) Trends in perinatal health in metropolitan France between 1995 and 2003: results from the National Perinatal Surveys. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) 35(4): 373-387.

- Blondel B, Lelong N, Kermarrec M, Goffinet F, National Coordination Group of the National Perinatal Surveys (2012) Trends in perinatal health in France from 1995 to 2010. Results from the French National Perinatal Surveys. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) 41(4): e1-15.

- Liu L, Johnson HL, Cousens S, Perin J, Scott S, et al. (2012) Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality: an updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000. Lancet Lond Engl 379(9832): 2151-2161.

- Ancel PY, Goffinet F, EPIPAGE-2 Writing Group, Kuhn P, Langer B, et al. (2015) Survival and morbidity of preterm children born at 22 through 34 weeks’ gestation in France in 2011: results of the EPIPAGE-2 cohort study. JAMA Pediatr 169(3): 230-238.

- Simeoni U (2013) Prematurity: from the perinatal period to adulthood. EMC-AKOS.

- Blank U, Vitte J (2015) Mast cell mediators. Rev Fr Allergol 55(1): 31-38.

- Vitte J, Bienvenu F (2012) Allergènes molé EMC-Biol Médicale. 8 août.

- Abraham SN, St John AL (2010) Mast cell-orchestrated immunity to pathogens. Nat Rev Immunol 10(6): 440-452.

- Kumar V, Sharma A (2010) Mast cells: emerging sentinel innate immune cells with diverse role in immunity. Mol Immunol 48(1-3): 14-25.

- St John AL, Abraham SN (2013) Innate immunity and its regulation by mast cells. J Immunol Baltim Md 1950 190(9): 4458-4463.

- Galli SJ, Nakae S, Tsai M (2005) Mast cells in the development of adaptive immune responses. Nat Immunol 6(2): 135-142.

- Marshall JS (2004) Mast-cell responses to pathogens. Nat Rev Immunol 4(10): 787-799.

- Theoharides TC, Kempuraj D, Tagen M, Conti P, Kalogeromitros D (2007) Differential release of mast cell mediators and the pathogenesis of inflammation. Immunol Rev 217: 65-78.

- Vitte J (2015) Human mast cell tryptase in biology and medicine. Mol Immunol 63(1): 18-24.

- (2017) INSERM. Allergie aux mé Tests immuno-biologiques.

- Schwartz LB, Bradford TR, Rouse C, Irani AM, Rasp G, et al. (1994) Development of a new, more sensitive immunoassay for human tryptase: use in systemic anaphylaxis. J Clin Immunol 14(3): 190-204.

- Ligi I (2011) Hématologie, immunologie et infections nosocomiales du prématuré. EMC-Pédiatrie-Mal Infect. 7(1): 1-9.

- Durandy A (2001) Development of specific immunity in prenatal life. Arch Pediatr Organe Off Soc Francaise Pediatr 8(9): 979-985.

- Millet V, Lacroze V, Bodiou AC, Dubus JC, D’Ercole C, et al. (1999) Ontogeny of the immune system. Arch Pediatr Organe Off Soc Francaise Pediatr 6(1): 14S-19S.

- Mussi-Pinhata MM, Rego MAC (2005) Immunological peculiarities of extremely preterm infants: a challenge for the prevention of nosocomial sepsis. J Pediatr (Rio J) 81(1): S59-68.

- Ramsay DB, Stephen S, Borum M, Voltaggio L, Doman DB (2010) Mast cells in gastrointestinal disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol 6(12): 772-777.

- Miner PB (1991) The role of the mast cell in clinical gastrointestinal disease with special reference to systemic mastocytosis. J Invest Dermatol 96(3): 40S-43S.

- Schultz ED, Potts EN, Mason SN, Foster WM, Auten RL (2010) Mast cells mediate hyperoxia-induced airway hyper-reactivity in newborn rats. Pediatr Res 68(1): 70-74.

- Wagenaar GTM, ter Horst SAJ, van Gastelen MA, Leijser LM, Mauad T, et al. (2004) Gene expression profile and histopathology of experimental bronchopulmonary dysplasia induced by prolonged oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med 36(6): 782-801.

- Lyle RE, Tryka AF, Griffin WS, Taylor BJ (1995) Tryptase immunoreactive mast cell hyperplasia in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatr Pulmonol 19(6): 336-343.

- Bhattacharya S, Go D, Krenitsky DL, Huyck HL, Solleti SK, et al. (2012) Genome-wide transcriptional profiling reveals connective tissue mast cell accumulation in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 186(4): 349-358.

- Nystedt S, Emilsson K, Wahlestedt C, Sundelin J (1994) Molecular cloning of a potential proteinase activated receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91(20): 9208-9212.

- Kawabata A, Kuroda R (2000) Protease-activated receptor (PAR), a novel family of G protein-coupled seven trans-membrane domain receptors: activation mechanisms and physiological roles. Jpn J Pharmacol 82(3): 171-174.

- Rouzaire P, Evrard B (2016) Tryptase et histamine. EMC-Biol Mé

- Belhocine W, Ibrahim Z, Grandné V, Buffat C, Robert P, et al. (2011) Total serum tryptase levels are higher in young infants. Pediatr Allergy Immunol Off Publ Eur Soc Pediatr Allergy Immunol 22(6): 600-607.

- Gonzalez-Quintela A, Vizcaino L, Gude F, Rey J, Meijide L, et al. (2010) Factors influencing serum total tryptase concentrations in a general adult population. Clin Chem Lab Med 48(5): 701-706.

- Christensen RD, Henry E, Jopling J, Wiedmeier SE. (2009) The CBC: reference ranges for neonates. Semin Perinatol 33(1): 3-11.

- Hannah ME, Ohlsson A, Farine D, Hewson SA, Hodnett ED, et al. (1996) Induction of labor compared with expectant management for prelabor rupture of the membranes at term. TERMPROM Study Group. N Engl J Med 334(16): 1005-1010.

- Seaward PG, Hannah ME, Myhr TL, Farine D, Ohlsson A, et al. (1998) International multicenter term PROM study: evaluation of predictors of neonatal infection in infants born to patients with premature rupture of membranes at term. Premature Rupture of the Membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 179(3): 635-639.

- Audra P, Garrec ML (2010) Rupture prématurée des membranes à terme et avant terme. EMC- Obsté

- Leviton A, Paneth N, Reuss ML, Susser M, Allred EN, et al. (1999) Maternal infection, fetal inflammatory response, and brain damage in very low birth weight infants. Developmental Epidemiology Network Investigators. Pediatr Res 46(5): 566-575.

- Watterberg KL, Demers LM, Scott SM, Murphy S (1996) Chorioamnionitis and early lung inflammation in infants in whom bronchopulmonary dysplasia develops. Pediatrics 97(2): 210-215.

- Yoon BH, Romero R, Kim KS, Park JS, Ki SH, et al. (1999) A systemic fetal inflammatory response and the development of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 181(4): 773-779.

- Guenova E, Volz T, Eichner M, Hoetzenecker W, Caroli U, et al. (2010) Basal serum tryptase as risk assessment for severe Hymenoptera sting reactions in elderly. Allergy 65(7): 919-923.

- Sahiner UM, Yavuz ST, Buyuktiryaki B, Cavkaytar O, Arik Yilmaz E, et al. (2014) Serum basal tryptase levels in healthy children: correlation between age and gender. Allergy Asthma Proc 35(5): 404-408.

- Kucharewicz I, Bodzenta-Lukaszyk A, Szymanski W, Mroczko B, Szmitkowski M (2007) Basal serum tryptase level correlates with severity of hymenoptera sting and age. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 17(2): 65-69.

- Angelidou A, Asadi S, Alysandratos KD, Karagkouni A, Kourembanas S, et al. (2012) Perinatal stress, brain inflammation and risk of autism-review and proposal. BMC Pediatr 12: 89.

- Cummins AG, Thompson FM (2002) Effect of breast milk and weaning on epithelial growth of the small intestine in humans. Gut 51(5): 748-754.

- Hawkes JS, Bryan DL, James MJ, Gibson RA (1996) Cytokines (IL-1beta, IL-6, TNF-alpha, TGF-beta1, and TGF-beta2) and prostaglandin E2 in human milk during the first three months postpartum. Pediatr Res 46(2): 194-199.

- Penttila IA, Flesch IEA, McCue AL, Powell BC, Zhou FH, et al. (2003) Maternal milk regulation of cell infiltration and interleukin 18 in the intestine of suckling rat pups. Gut 52(11): 1579-1586.

- Zhang M, Zola H, Read L, Penttila I (2001) Identification of soluble transforming growth factor-beta receptor III (sTbetaIII) in rat milk. Immunol Cell Biol 79(3): 291-297.

- Penttila I (2006) Effects of transforming growth factor-beta and formula feeding on systemic immune responses to dietary beta-lactoglobulin in allergy-prone rats. Pediatr Res 59(5): 650-655.

- Penttila IA, van Spriel AB, Zhang MF, Xian CJ, Steeb CB, et al. (1998) Transforming growth factor-beta levels in maternal milk and expression in postnatal rat duodenum and ileum. Pediatr Res 44(4): 524-531.

- Zemann B, Schwaerzler C, Griot-Wenk M, Nefzger M, Mayer P, et al. (2003) Oral administration of specific antigens to allergy-prone infant dogs induces IL-10 and TGF-beta expression and prevents allergy in adult life. J Allergy Clin Immunol 111(5): 1069-1075.

- Di Sabatino A, Pickard KM, Rampton D, Kruidenier L, Rovedatti L, et al. (2008) Blockade of transforming growth factor beta upregulates T-box transcription factor T-bet, and increases T helper cell type 1 cytokine and matrix metalloproteinase-3 production in the human gut mucosa. Gut 57(5): 605-612.

- Tooley KL, Howarth GS, Butler RN, Lymn KA, Penttila IA (2009) The effects of formula feeding on physiological and immunological parameters in the gut of neonatal rats. Dig Dis Sci 54(7): 1432-1439.

- Dvorak B, McWilliam DL, Williams CS, Dominguez JA, Machen NW, et al. (2000) Artificial formula induces precocious maturation of the small intestine of artificially reared suckling rats. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 31(2): 162-169.

- Sly LM, Rauh MJ, Kalesnikoff J, Song CH, Krystal G (2004) LPS-induced upregulation of SHIP is essential for endotoxin tolerance. Immunity 21(2): 227-239.

- Neu J, Walker WA (2011) Necrotizing enterocolitis. N Engl J Med 364(3): 255-264.

- Hodzic Z, Bolock AM, Good M (2017) The Role of Mucosal Immunity in the Pathogenesis of Necrotizing Enterocolitis. Front Pediatr 5(2): 40.

- Clark DA, Munshi UK (2014) Feeding associated neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis (Primary NEC) is an inflammatory bowel disease. Pathophysiol Off J Int Soc Pathophysiol 21(1): 29-34.

- Markel TA, Crisostomo PR, Wairiuko GM, Pitcher J, Tsai BM, et al. (2006) Cytokines in necrotizing enterocolitis. Shock Augusta Ga 25(4): 329-337.

- Mukaida N (2000) Interleukin-8: an expanding universe beyond neutrophil chemotaxis and activation. Int J Hematol 72(4): 391-398.

- Nanthakumar NN, Fusunyan RD, Sanderson I, Walker WA (2000) Inflammation in the developing human intestine: A possible pathophysiologic contribution to necrotizing enterocolitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97(11): 6043-6048.

- Martin CR, Walker WA (2006) Intestinal immune defences and the inflammatory response in necrotising enterocolitis. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 11(5): 369-377.

- Sandig H, Bulfone-Paus S (2012) TLR signaling in mast cells: common and unique features. Front Immunol 3: 185.

- Keck S, Müller I, Fejer G, Savic I, Tchaptchet S, et al. (2011) Absence of TRIF signaling in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated murine mast cells. J Immunol Baltim Md 1950 186(9): 5478-5488.

- Niño DF, Sodhi CP, Hackam DJ (2016) Necrotizing enterocolitis: new insights into pathogenesis and mechanisms. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 13(10): 590-600.

- Afrazi A, Sodhi CP, Richardson W, Neal M, Good M, et al. (2011) New Insights into the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Necrotizing Enterocolitis: Toll-like Receptors and Beyond. Pediatr Res 69(3): 183.

- Armstrong L, Medford ARL, Uppington KM, Robertson J, Witherden IR, et al. (2004) Expression of functional toll-like receptor-2 and -4 on alveolar epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 31(2): 241-245.

- Jiang D, Liang J, Fan J, Yu S, Chen S, et al. (2005) Regulation of lung injury and repair by Toll-like receptors and hyaluronan. Nat Med 11(11): 1173-1179.

- Hillman NH, Moss TJM, Kallapur SG, Bachurski C, Pillow JJ, et al. (2007) Brief, large tidal volume ventilation initiates lung injury and a systemic response in fetal sheep. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 176(6): 575-581.

- Blackwell TS, Hipps AN, Yamamoto Y, Han W, Barham WJ, et al. (2011) NF-κB signaling in fetal lung macrophages disrupts airway morphogenesis. J Immunol Baltim 187(5): 2740-2747.

- Kleeberger SR, Reddy S, Zhang LY, Jedlicka AE (2000) Genetic susceptibility to ozone-induced lung hyperpermeability: role of toll-like receptor 4. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 22(5): 620-627.

- Zhang X, Shan P, Qureshi S, Homer R, Medzhitov R, et al. (2005) Cutting edge: TLR4 deficiency confers susceptibility to lethal oxidant lung injury. J Immunol Baltim 175(8): 4834-4838.

- Qureshi ST, Zhang X, Aberg E, Bousette N, Giaid A, et al. (2006) Inducible activation of TLR4 confers resistance to hyperoxia-induced pulmonary apoptosis. J Immunol Baltim 176(8): 4950-4958.

- Lal CV, Ambalavanan N (2015) Genetic Predisposition to Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. Semin Perinatol 39(8): 584.

- Lavoie PM, Ladd M, Hirschfeld AF, Huusko J, Mahlman M, et al. (2012) Influence of common non-synonymous Toll-like receptor 4 polymorphisms on bronchopulmonary dysplasia and prematurity in human infants. PloS One 7(2): e31351.

- Carrera P, Di Resta C, Volonteri C, Castiglioni E, Bonfiglio S, et al. (2015) Exome sequencing and pathway analysis for identification of genetic variability relevant for bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) in preterm newborns: A pilot study. Clin Chim Acta Int J Clin Chem 451(Pt A): 39-45.

Research Article

Research Article