Clinical Summary

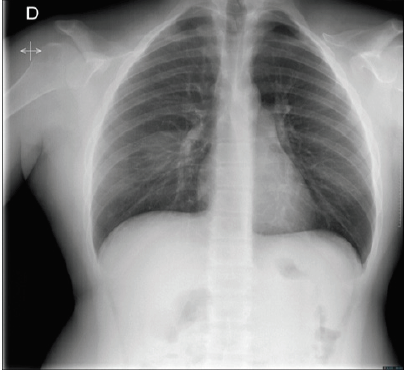

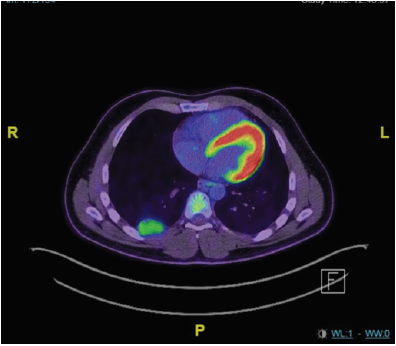

A 25 years old gentleman was brought to the emergency department after a high-velocity car accident. Assessment of Airways, Breathing and Circulation was unremarkable. Glasgow Coma Scale was 15. Apart from seat-belt sign, there were no signs of injury on clinical examination. Meanwhile, the examination revealed a patient with a short stature (163 cm), small head with frontal bossing, bilateral genu valgum and brachydactyly. Extreme shoulders’ mobility made shoulder apposition to each other feasible. Extended Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma revealed no abnormality. Chest x-ray is showed in Figure 1. Total body Computed Tomography (CT) showed no significant abnormality but a 4 cm well-defined posterior chest wall tumor. His past medical history was remarkable for extraction of dozens of fragments of teethes. In his family history, his father and grandmother showed a similar phenotype. After a few hours of monitoring, the patient was discharged home with a planned follow-up chest imaging. On magnetic resonance imaging three months later, the tumor was stable in size and did not show sign of invasiveness. Key picture of fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography fused with CT is depicted in Figure 2. After multidisciplinary tumor board discussion, decision for upfront surgical removal of the tumor was made. Thoracoscopic tumor excision was performed with an uneventful postoperative course.

Figure 2: Fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography fused with CT showed moderate intensity of the right chest wall tumor with a maximal standard uptake value of 2.9.

Questions

What is the genetic syndrome the patient is suffering from? What is your presumed diagnosis regarding the chest wall tumor? Many genetic syndromes predispose to specific tumors. Is it the case in this patient?

Answer

Intraoperatively, the tumor was pedunculated on the intercostal

space. Histopathologic examination of the specimen revealed a

benign tumor, namely an intercostal nerve schwannoma. The patient

is affected by Cleido-Cranial Dysplasia (CCD). This condition was first

described by Marie and Sainton in 1898 [1]. It is a rare autosomal

dominant skeletal disorder with a prevalence of one per million [2].

It is characterized by short stature, brachycephaly, delayed closure

of the fontanelles and sutures, Wormian bones, midface hypoplasia,

delayed eruption of permanent teeth, supernumerary permanent

teeth, aplasia or hypoplasia of the clavicles, and other skeletal

abnormalities such as hypoplastic iliac wings, and brachydactyly

[3]. CCD is caused by mutations in RUNX2 gene, which is mapped to

6p21 chromosome [3]. RUNX2 plays a key role in osteogenesis and

osteoblast precursor cell differentiation [3]. Here, the presence of

c.685+1G>A mutation of RUNX2 on molecular analysis confirmed

the diagnosis of CCD.

The association of CCD and schwannoma has been rarely

reported. Pattisapu, et al. [4] described a patient with paraparesis

due to spinal cord compression at the T1 level with a good clinical

outcome one year after resection of the schwannoma. The second

patient was described by Scherer, et al. [5] She suffered from ataxia,

headache and hearing loss secondary to vestibular schwannoma [5].

Both authors speculated a common origin for CCD and schwannoma

since both disorders may arise from mesodermal abnormalities

[4,5]. This is the third report showing this unusual association.

Despite the low prevalence of CCD, we hope future reports will

elucidate whether the association of CCD and schwannoma is more

than just a coincidence.

References

- Marie P, Sainton P (1898) Sur la dysostose cleidiocranienne hereditaire. Rev Neurol 6: 835-838.

- Lee KE (2013) RUNX2 mutations in cleidocranial dysplasia. Genetics and molecular research : GMR 12(4): 4567-4574.

- Cohen MM (2001) RUNX genes, neoplasia, and cleidocranial dysplasia. American journal of medical genetics 104(3): 185-188.

- Pattisapu J, Miller JD, Sanford RA (1986) Cleidocranial dysostosis and schwannoma. Neurosurgery 18(6): 827-828.

- Scherer A, Messing Junger AM, Lackmann GM (2001) Cleidocranial dysostosis, unilateral sensorineural hearing loss and gait disturbances: a clear-cut case of diagnostic mimicry? Neuropediatrics 32(5): 275-276.

Case Report

Case Report