Abstract

Clozapine is a very effective anti-psychotic agent accompanied by severe adverse effects such as neutropenia and cardiotoxicity. The present report is an attempt to describe a case of a patient with underlying heart disease, who developed clozapine-induced dilated cardiomyopathy and experienced clinical and echocardiographical improvement under supportive measures and drug discontinuation. The drug’s cardiotoxic effect is furtherly discussed from a pathophysiological and therapeutic point of view.

Abbreviations: SGA: Second-Generation Antipsychotic Drug; EF: Ejection Fraction; MR: Mitral Regurgitation; MV: Mitral Valve; IVS: Intraventricular Septum; LV: Left Ventricle; LA: Left Atrium; IVC: Inferior Vena Cava; TR: Tricuspid Regurgitation; CBC: Complete Blood Count

Introduction

Ever since clozapine’s introduction, as a second-generation antipsychotic drug (SGA), it is thought to be one of the most effective drugs against refractory schizophrenia. Clinical trials have identified its superiority against other SGAs presenting, overall, improved quality of life of first-line treatment-resistant schizophrenic patients. Among others, clozapine has been linked to better compliance, reduction of positive (delusions or hallucinations) and negative (such as lack of speech, depression, etc.) symptoms, and less suicidality [1]. Due to those beneficiary effects, based on different published evidence, it is recommended by many clinical practice guidelines as the gold standard to refractory schizophrenia. Although lacking extrapyramidal adverse effects, contrary to chlorpromazine, haloperidol, and other antipsychotic agents, it is accompanied by a wide range of severe or mild adverse effects including blood dyscrasia - neutropenia, cardiotoxicity, seizures, and sedation, hypotension, constipation, or metabolic syndrome which may be the cause of drug discontinuation [2,3]. It is of note that clozapine-associated cardiotoxicity requires close patient monitoring and can develop different manifestations including myocarditis, cardiomyopathy, and subclinical cardiac toxicity, caused by different pathophysiological and histological mechanisms.

Aim

The present study aims to present a case of a 65-year-old man under clozapine for the last 5 years, due to refractory schizophrenia and has been developing recurrent episodes of cardiac failure. Besides, pathophysiological and therapeutic measures of clozapinerelated cardiotoxicity are furtherly discussed, to unravel the way those patients should be managed.

Case Report

A 65-year-old male patient, who was under clozapine for the last five years, experienced repeated episodes of hospital admissions in the Cardiology Unit due to cardiac deterioration. The patient had experienced acute coronary syndrome two years ago, and underwent coronary angiography, presenting (LAD 100%, RCA 100%), which could not be treated surgically, based on cardiothoracic consultation. Heart failure was classified as ΝΥΗΑ ΙΙΙ - IV (HFrEF), preserving an ejection fraction (EF) = 20– 25%. He also suffered from moderate to serious Mitral Regurgitation (MR). For those prementioned conditions he was under Furosemide 40 mg (gradual dose increase from S: 1*1 to S: 1*2 to 500 mg S: 1/4*1), Carvedilol 6,25mg S: 1*2, Aspirine 100mg S: 1*1, Eplerenone 25 mg S: 1*1, Ivabradine 5 mg S: 1*2, Atorvastatin / Ezetimibe 10 / 20 mg S:1*1, Clozapine 200 mg S: 1*2. On physical examination, the patient had rhythmic cardiac auscultation (S1, S2) and a systolic murmur of Mitral Valve (MV) +3/6. Pulmonary auscultation revealed diminished breath pneumonic sounds at the right lower and middle pulmonary lobe, crackles at the left lower lobe, and prolonged expiration. Upon abdomen palpation, a positive hepatojugular sign and substantial ascites were observed. The patient had lower extremities edema with indentation and vital signs BP = 100/60 mmHg, HR = 95/ min, SpO2 = 90%.

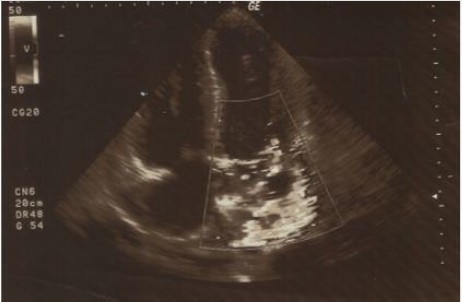

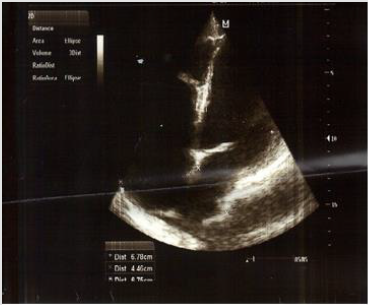

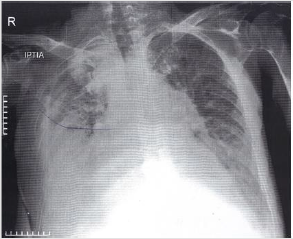

The ECG revealed SR tachycardia, with no signs of cardiac ischemia and repolarization abnormalities of the lateral cardiac wall. Echocardiography (shown in Figures 1 & 2) revealed EF = 20 – 25%, apical hypokinesia of left ventricle (LV), medial intraventricular septum (IVS) and lateral wall hypokinesia, LV enlargement: 68 mm, medium left atrium (LA) enlargement: 48 mm (LA area = 36 cm2 ), MR + 2/4, tricuspid regurgitation (TR) + 2/4, inferior vena cava (IVC) = 22 mm, with minimum breathing fluctuation during inhalation. Chest x-ray (shown in Figure 3) revealed cardiomegaly, congestion of lung hilum, reversion of pulmonary blood irrigation, and right pleural effusion. Upon admission, the patient was administered inotropic and diuretic treatment and underwent pleural and ascitic paracentesis several times. Biochemical and cytological examination of the paracentesis fluids didn’t show signs of inflammation. After stabilization of the patient’s clinical condition, he was admitted to a rehabilitation center, where the psychiatrist in charge ordered clozapine discontinuation and olanzapine commencement. The patient was followed by the Cardiology Unit as an outpatient and three months later, achieved an EF: 35- 40%. Although the patient had a positive cardiac history, clozapine-induced dilated cardiomyopathy was diagnosed, a fact that was confirmed with the improved clinical condition of the patient when the drug’s administration stopped.

Discussion

As prementioned, clozapine cardiotoxicity may develop

in different types of presentation such as myocarditis, dilated

cardiomyopathy, or even subclinical cardiotoxicity, clinical

conditions that are associated with 10% mortality rates [3,4].

Although there is no clinical evidence that those adverse effects

are dose-related, they could be life-threatening, and require close

clinical and laboratory monitoring, including troponin T or I,

CRP, and echocardiography [5]. Besides, the drug’s prescription

is recommended to be done with caution among patients with

underlying heart disease and to be avoided among patients with

severe underlying heart disease [4]. Further cardiological side

effects are benign tachycardia (increase 10- 15 bpm on average),

QT prolongation (>500msec), and orthostatic hypotension.

Clozapine-induced myocarditis is an IgE mediated

(hypersensitivity Type I) myocardium inflammation presenting

with fever and signs of acute heart failure. Clinical symptomatology

of the disease is unclear posing an impact in urgent and accurate

diagnosis and treatment. Myocarditis takes place during the first

two months of drug commencement and most cases are diagnosed

during the first three weeks [6].

Therapeutic measures include supportive and preventive

treatment to avoid cardiac overload and prevention of heart failure,

whereas drug discontinuation is the key to the patient’s clinical

and biochemical improvement [7,8]. Mortality rates of clozapineinduced

myocarditis can reach 21%, a much higher rate than that

observed among the general population [6]. Clozapine rechallenge

is in general not recommended among those patients, although low

dose and slow dose increase could be attempted, with the patient

under close cardiology monitoring [3].

Clozapine-induced dilated cardiomyopathy presents with the

main symptoms of cardiac failure (see the clinical presentation

of our patient) and is diagnosed with echo findings, especially

reduced EF and thin and dilated LV wall [3]. Although the exact

pathophysiological mechanism of myocardial toxicity is unclear, the

predominant path is IgE-mediated myocardial damage accompanied

by eosinophilia or direct myocardial toxicity. This manifestation

presents 4 weeks to years after the administration of the drug and

is a rare adverse effect, affecting 1 among 1000 clozapine treated

patients [4]. Apart from ECG and basic biochemical testing, NTproBNP

provides further diagnostic information [4].Supportive

treatment and patient stabilization are of note, accompanied

by drug discontinuation. Most cases that have not experienced

severe myocardial damage, achieve complete recovery after drug

discontinuation and clozapine re- challenge could be attempted

under close cardiology monitoring algorithm proposed by Cook, et

al. [9]. Subclinical heart dysfunction presenting with no symptoms or mild tachycardia has been reported in 33% of young previously

healthy clozapine patients [10]. The cause of this adverse effect

has been linked to systematic inflammation, so as a result close

cardiological, echocardiography, and biochemical monitoring of the

patients are required both for prevention and treatment. B-blockers

or ivabradine administration are indicated in these cases [11]. Last

but not least, clozapine commencement may induce neutropenia or

other forms of blood dyscrasia such as leukopenia or thrombopenia,

especially during the first 18 weeks of drug administration. GSF can

be used to stimulate granulocytes’ production along with lithium

administration. This condition may be severe, and potentially lifethreatening,

however, drug discontinuation and the prementioned

supportive measures can reverse the phenomenon [10].

Conclusion

30% of psychotic patients fail to respond to first-line therapy. Clozapine is a very effective antipsychotic drug, which is under prescribed due to its severe side effects (blood dyscrasia and cardiotoxicity). To achieve proper adverse effect prevention or accurate diagnosis, from a cardiology point of view, a baseline cardiology consultation is required (including patient’s history, echocardiography- EF, biochemical testing), before drug administration, and close contact between the psychiatrist in charge and the cardiologist, to identify and treat in time any adverse effect. From a hematological point of view, a complete blood count (CBC) is required before drug prescription, a test that should be repeated every week for the first 18 weeks.

References

- S Subramanian, BA Völlm, N Huband (2017) Clozapine dose for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017(6): CD009555.

- S Warnez, S Alessi Severini (2014) Clozapine: A review of clinical practice guidelines and prescribing trends. BMC Psychiatry 14: 102.

- G Kanniah, S Kumar (2020) Clozapine associated cardiotoxicity: Issues, challenges and way forward. Asian J Psychiatr 50: 101950.

- RK Patel, AM Moore, S Piper, M Sweeney, E Whiskey, et al. (2019) Clozapine and cardiotoxicity - A guide for psychiatrists written by cardiologists. Psychiatry Research 282: 112491.

- K N Knoph, RJ Morgan, BA Palmer, KM Schak, AC Owen, et al. (2018) Clozapine-induced cardiomyopathy and myocarditis monitoring: A systematic review. Schizophr Res 199: 17-30.

- BL Bellissima, MD Tingle, A Cicović, M Alawami, C Kenedi (2018) A systematic review of clozapine-induced myocarditis. Int J Cardiol 259: 122-129.

- S Annamraju, B Sheitman, S Saik, A Stephenson (2007) Early recognition of clozapine-induced myocarditis. J Clin Psychopharmacol 27(5): 479-483.

- D De Berardis, N Serroni, D Campanella, L Olivieri, F Ferri, et al. (2012) Update on the Adverse Effects of Clozapine: Focus on Myocarditis. Curr Drug Saf 7(1): 55-62.

- SC Cook, BA Ferguson, RO Cotes, TW Heinrich, AC Schwartz (2015) Clozapine-Induced Myocarditis: Prevention and Considerations in Rechallenge. Psychosomatics 56(6): 685-690.

- C Rostagno, S Domenichetti, F Pastorelli, GF Gensini (2011) Usefulness of NT-Pro-BNP and Echocardiography in the Diagnosis of Subclinical Clozapine-Related Cardiotoxicity. J Clin Psychopharmacol 31(6): 712-716.

- J Lally, J Brook, T Dixon, F Gaughran, S Shergill, et al. (2014) Ivabradine, a novel treatment for clozapine- induced sinus tachycardia : a case series. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol Orig 4(3): 117-122.

Case Report

Case Report