Abstract

Purpose: This study aims to assess the racial health disparities in the healthrelated quality of life (HRQoL) among the U.S. Hispanic hyperlipidemia population with comorbidities

Patients and Methods: This cross-sectional study used the 2014-2015 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) data. HRQoL measurement was done using the SF- 12 PCS and SF-12 MCS surveys. Inferential statistics comprising of chi square tests of differences and multivariate regression analyses were conducted to determine HRQoL in the U.S. residing Hispanic population with hyperlipidemia. The regression statistics were performed for both SF-12 PCS and SF-12 MCS surveys.

Results: The study sample included 13,933 Hispanics residing in the U.S. out of which 14.2% (n=1,985) had hyperlipidemia. Controlling for covariates, U.S. Hispanics with hyperlipidemia had significantly lower SF-12 PCS (-3.85, SE=0.49; p<0.001) and SF-12 MCS (-2.77, SE=0.49; p<0.001) scores compared to U.S. Hispanics without hyperlipidemia respectively. The lone predictor for SF-12 PCS scores was age whereas marital status, high school education and poverty level were predictors for SF-12 MCS scores. Compared to U.S. Hispanics with no comorbidities, U.S. Hispanics with three or more comorbidities had significantly lower SF-12 PCS (-2.36, SE=0.28; p<0.001) and SF- 12 MCS (-2.59, SE=0.27; p<0.001) scores respectively.

Conclusion: Further research is needed to understand the impact of chronic diseases including hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes, hypertension (HTN) and chronic heart failure (CHF) on HRQoL in other minorities such as African Americans and Native Americans.

Keywords: Hyperlipidemia; Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL); Hispanic Population

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is reported to cause one in three deaths each year in the United States (U.S.) with approximately half of Americans having at least one of the major clinical risk factors: high low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, hypertension, or smoking [1,2]. Treating hyperlipidemia and hypertension, along with promoting smoking cessation demonstrates a high potential to prevent CVD related deaths [2]. CVD is also a major cause of disability in the U.S. The estimated annual direct costs of CVD are projected to triple from $273 billion to $818 billion from 2010 to 2030 respectively [3]. By 2030, the estimated total cost of CVD will surpass $1 trillion including both direct and indirect costs associated with the disease. Cost of CVD is not the only thing projected to increase by the year 2030. Prevalence of CVD is projected to increase by about 10% during this time period. Previously, life expectancy and causes of death were utilized as key indicators of population health [4]; however, simply juxtaposing population life expectancy with overall population health does not provide any meaningful information on the quality of population health in regard to physical, mental, and social domains.

Given the expected increase in healthcare expenditures attributed to CVD in the coming decade, it is imperative to highlight the quality years lived among patients with CVD. Key health indicators such as health-related quality of life (HRQoL) incorporate domains of physical, mental, emotional, and social functioning of individuals with emphasis on quality-of-life consequences of health status [4,5]. In addition, HRQoL is measured by patient’s perception of his or her physical and mental well-being. The American Heart Association classifies high cholesterol as a major risk factor for CVD. Per the 2018 cholesterol treatment guidelines, 56 million U.S. adults qualify for statin therapy. Among adolescents aged 6-19, around 21% have at least one cholesterol measurement not within goal range [6]. While hyperlipidemia is considered an asymptomatic condition, comorbidities such as type 2 diabetes (T2DM), hypertension, and depression in conjunction with hyperlipidemia can define a clearer association of CVD with HRQoL [7].

A substantial proportion of patients, approximately 73 million who experience elevated LDL cholesterol levels, are currently not meeting LDL cholesterol goals in the U.S [8]. Notable changes in clinical guidelines for treatment of hyperlipidemia emphasize LDL cholesterol control. From Adult Treatment Panel (ATP) III to American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA), new guidelines discuss substantial benefits in reducing the burden of hyperlipidemia by focusing on controlling LDL levels [9]. Evidence demonstrates that LDL cholesterol is a principal driver of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), which is the underlying cause of most clinical manifestations of CVD as well as the primary target for CVD risk reduction interventions [10-12].

In the general population as well as patients with ASCVD, hyperlipidemia has been consistently shown to be associated with worse outcomes in regard to mortality and cardiovascular outcomes [13]. However, there is inconclusive evidence to demonstrate an inverse relationship between cholesterol levels and health outcomes in patients with established co-morbid conditions such as heart failure [14]. In essence, low cholesterol levels have been shown to be independently associated with increased mortality and high cholesterol levels with improved survival. It is unclear whether low cholesterol levels play a causative role in the worse outcomes of patients with comorbid conditions such as heart failure or if low cholesterol levels merely reflect an advanced disease state. This inconsistency in evidence seems to be a contributing factor to the gap in health literature among patients with hyperlipidemia.

Hyttinen et al. [15] used the RAND-36 questionnaire to measure HRQoL and mortality [15]. High cholesterol significantly affected physical functioning but not mental functioning score in the questionnaire. Mortality and cholesterol shows no significant association. Most HRQoL scales were self-reported in a study clinic, or mailed to the patients to complete at home. Interventions in assessing scales could include conducting HRQoL measures in clinics by their physicians who have known them and established a more credible relationship with them. The RAND-36 scale evaluates different aspects of HRQoL including physical functioning, role limitations caused by health problems, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role limitations caused by emotional problems, and mental health. Different ethnicities, genders, and geographical regions can be studied more in depth to explore the correlation between co-morbidities and depression. Socioeconomic status can also be studied because it plays a major role in patient’s ability to obtain medications and modify their diet and lifestyle [15].

Relatively few studies have measured the HRQoL associated with hyperlipidemia, giving inconsistent results [16]. In a metaanalysis on HRQol associated with familial hypercholesterolemia, they found that women, patients with hypertension or another chronic disease, patients with higher risk of CVD, and patients who felt forced to participate in cholesterol screening demonstrated higher anxiety score levels. Older patients and patients with chronic diseases demonstrated higher depression score levels [17]. Einvik et al. [16] measured depression and anxiety status associated with hyperlipidemia diagnosis and dietary counseling over three years. The diet and omega-3 intervention trial (DOIT) on atherosclerosis utilized three scales to measure anxiety and depression. Patients diagnosed with hyperlipidemia reported significantly more episodes of anxiety throughout the trial [16]. A major challenge in assessing HRQoL associated with hyperlipidemia is the asymptomatic nature of the disease, lifetime therapy requirement, and LDL-cholesterol, being the intermediate health outcome rather than terminal outcome of interest (i.e. myocardial infarction) [18]. Another major challenge is the racial and ethnic disparities in the treatment of hyperlipidemia. Racial and ethnic disparities can affect cardiovascular risk factors. In the U.S., hyperlipidemia disproportionately affects Hispanic population.

Hispanic patients are less likely to have their cholesterol checked or use cholesterol-lowering medications. Minority patients, which includes Hispanics, were found to have lower overall knowledge about hyperlipidemia and stated that the provider made the final decision in their medications [19]. An additional challenge is the inconsistency of evidence in the association of hyperlipidemia with comorbid conditions. One study by Smith and Singleton suggests that dyslipidemia in conjunction with diabetes can enhance a patient’s risk for diabetic neuropathy [20]. Another study conducted by Shih et al. found that hyperlipidemia poses an increased risk for men to develop benign prostatic hyperplasia. From these studies, hyperlipidemia can be associated with at least two comorbidities, making it a dynamic and challenging disease [21]. Therefore, LDL cholesterol with co-morbid conditions should be scrutinized concomitantly in terms of HRQoL.

The Hispanic population in the U.S. lives disproportionately under the poverty line and have lower rates of health insurance compared to other ethnic minorities [22]. A study conducted using the 2014-2015 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) dataset found that in the U.S., HRQoL was lower among Hispanics who had hypertension compared to Hispanics who did not have hypertension [23]. Another study assessing the 2000 and 2002 MEPS dataset found that among U.S. residing adults, obesity exacerbates the negative relationship of diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension with HRQoL, health function and health perception [24]. This study determines the comorbidity status in the U.S. Hispanic population with hyperlipidemia. The study also assesses racial disparities in HRQoL among the U.S. Hispanic population with hyperlipidemia and comorbidities.

Methods

Data Source

Data was collected from the 2014 to 2015 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) in order to use in this cross-sectional analysis study. MEPS contains numerous surveys from across the United States, which has had more of a focus on the healthcare system in the U.S. Information from MEPS is collected from across the U.S., including their healthcare utilization, coverage, access, as well as behaviors related to their health and the U.S. healthcare system. Since MEPS data is publicly available and all data is de-identified, Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was waived for this study.

Study Population

The study population of interest were Hispanics living in the U.S. with hyperlipidemia. Inclusion criteria was: (1) being Hispanic, (2) having a diagnosis of hyperlipidemia, (3) completing the 12-item short form survey for both physical health (SF-12 PCS) and mental health (SF-12 MCS), and (4) aged 18 years or older. Hyperlipidemia was defined using MEPS medical condition files and HRQoL was defined using MEPS full-year consolidated files.

Variable Measurement

The variables in this study were hyperlipidemia in Hispanics in the U.S. as the primary independent variable and HRQoL as the dependent variable. HRQoL was measured using the SF-12 PCS and SF-12 MCS surveys. SF-12 PCS scores are known indicators among groups which have different physical limitations, and SF-12 PCS scores are known indicators among groups with and without cognitive limitations. Co-variates used in this study for analyses were age, gender, Hispanic ethnicity, region of U.S., type of health insurance, marital status, education level, BMI level, and Charlson co-morbidity index (CCI).

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis used was Chi square tests of differences for characteristics related to having had a previous diagnosis of hyperlipidemia among Hispanics in the U.S. Multivariate regression models were conducted and used for both SF-12 PCS and SF-12 MCS surveys to predict HRQoL among Hispanics in the U.S. with a previous diagnosis of hyperlipidemia, controlling for co-variates. The α level for statistical significance was set at 0.05. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, U.S.) and Stata/SE 14.1 (STATA Corp., College Station, TX, U.S.).

Results

Patient Characteristics

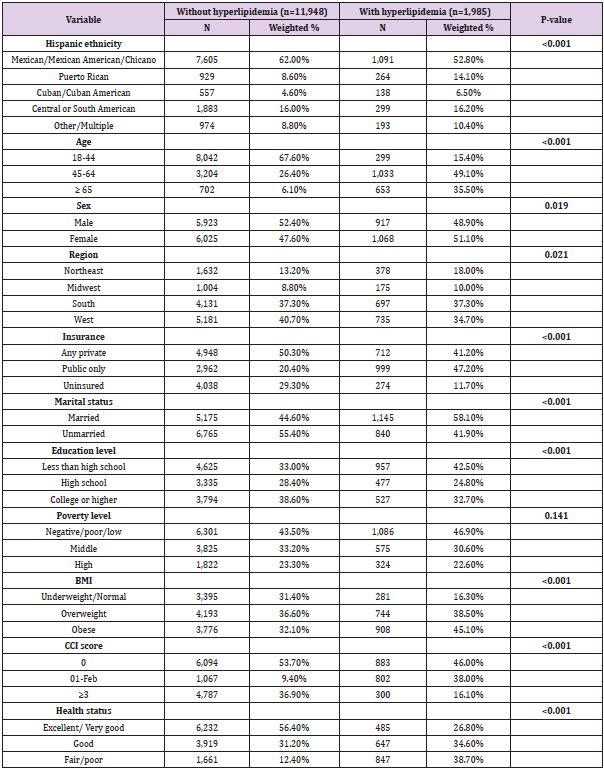

In Table 1, sample characteristics of U.S. Hispanics are shown. The sample population in this study was 13,933 Hispanics in the U.S. Of this sample, 14.2% (n = 1,985) had a diagnosis of hyperlipidemia. Hispanic ethnicity, age group, sex, region, insurance type, marital status, education level, BMI level, and CCI show a significant association with having hyperlipidemia (p<0.001), compared to those without hyperlipidemia, using Chi square tests.

SF-12 Scores

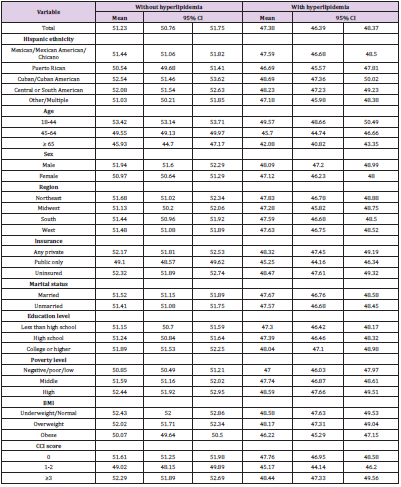

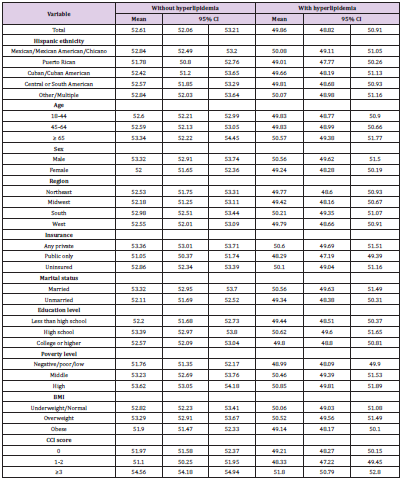

In Table 2, the SF-12 PCS scores are shown with a 95% confidence interval (CI) for Hispanics without and with hyperlipidemia. The overall scores for Hispanics without hyperlipidemia were 51.23 (50.76-51.75), versus Hispanics with hyperlipidemia being 47.38 (46.39-48.37). In Table 3, the SF-12 MCS scores are shown with a 95% CI for Hispanics without and with hyperlipidemia. The overall scores for Hispanics without hyperlipidemia were 52.61 (52.06- 53.21), versus Hispanics with hyperlipidemia being 49.86 (48.82- 50.91).

Table 2. Estimated SF-12 physical health composite scale (PCS) scores by hyperlipidemia status in U.S. Hispanic adults.

Table 3. Estimated SF-12 physical health composite scale (PCS) scores by hyperlipidemia status in U.S. Hispanic adults.

Factors Associated with Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL)

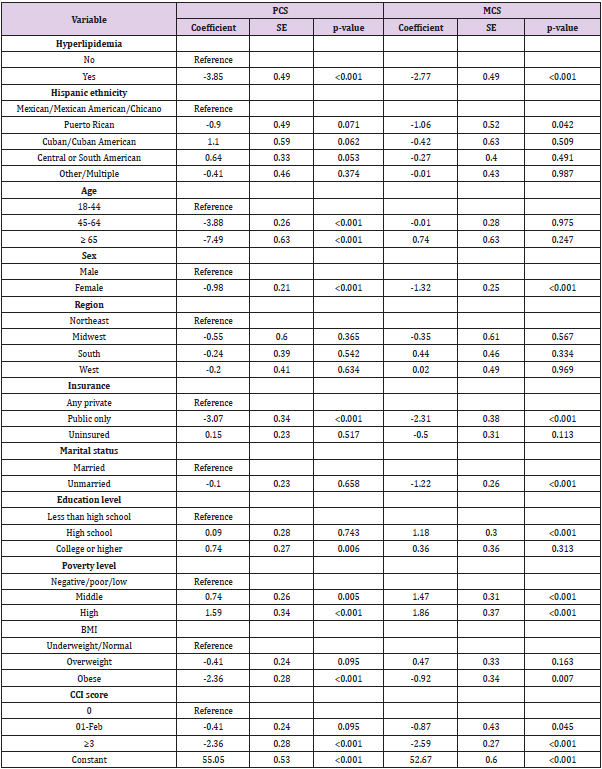

In Table 4, the HRQoL factors associated in the U.S. Hispanic population with hyperlipidemia are shown and summarized, using two multivariate regression analyses; one for SF-12 PCS and one for SF-12 MCS, while controlling for co-variates. For both SF- 12 PCS and SF-12 MCS scores, the analysis shows that Hispanics with hyperlipidemia had significantly lower scores compared to Hispanics without hyperlipidemia. The regression coefficients (b) were –3.85 (SE=0.49; p<0.001) for SF-12 PCS and –2.77 (SE=0.49, p<0.001) for SF-12 MCS for Hispanics with hyperlipidemia, controlling for covariates. This indicates the scores for Hispanics with hyperlipidemia were 3.85 and 2.77 points lower for SF-12 PCS and SF-12 MCS, respectively, compared to Hispanics without hyperlipidemia. Sex, having public insurance, having a high poverty level, and having three or more co-morbidities were associated with both SF-12 PCS and SF-12 MCS scores. Age was the sole factor to have an association with SF-12 PCS score only, while marital status, having a high school education, and having a middle poverty level had an association with SF-12 MCS score only.

Table 4. Hispanic ethnicity and other factors associated with health-related quality of life among U.S. Hispanic adults (multiple regression; controlling for covariates).

Among Hispanics ages 45-64 and 65 or older, SF-12 PCS scores lowered by 3.88 (SE 0.26) and 7.49 (SE=0.63) points, respectively, when compared to Hispanics ages 18-44 (p<0.001). Hispanic females scores lowered by 0.98 (SE=0.21) and 1.32 (SE=0.25) points for SF-12 PCS and SF-12 MCS, respectively, compared to Hispanic males (p<0.001). SF-12 PCS scores lowered by 3.07 (SE=0.34) and SF-12 MCS scores lowered by 2.31 (SE=0.38) for Hispanics on public health insurance compared to those with private insurance (p<0.001). Hispanics with three or more co-morbidities had scores lowered by 2.36 (SE=0.28) and 2.59 (SE=0.27) for SF-12 PCS and SF-12 MCS, respectively, compared to Hispanics with none (p<0.001). Unmarried Hispanics SF-12 MCS scores lowered by 1.22 (SE=0.26) versus married (p<0.001). SF-12 MCS scores increased for Hispanics with at least a high school education by 1.18 (SE=0.30; p<0.001). Having high level of poverty increased SF-12 PCS scores by 1.59 (SE=0.34; p<0.001), and SF-12 MCS scores increased by 1.47 (SE=0.31) for middle level poverty and 1.86 (SE=0.37) for high level poverty (p<0.001).

Discussion

HRQoL combines both physical and mental aspects of health, which gives a better understanding of patients’ overall wellbeing. This is one of the few studies evaluating HRQoL among U.S. Hispanic patients with hyperlipidemia using the MEPS database. We identified that perceived health status affected both the mental and physical domains of health among Hispanic hyperlipidemia patients. Physical health was found to deteriorate with increasing age, lower income, and having government insurance. Mental health was also found to deteriorate with increased age, being unmarried, lower income, and having government insurance. In addition, the number of coexisting chronic diseases was inversely proportional to the HRQoL measured in PCS and MCS. We found that the most common coexisting diseases for hyperlipidemia patients were hypertension (HTN), diabetes, mood disorders, chronic heart failure (CHD), and kidney disease.

Our study showed that mood disorders the most in Hispanic patients with hyperlipidemia significantly impacted their mental health scores. Considering the association between hyperlipidemia and mental health, certain disease pathways could demonstrate this connection. Hyperlipidemia is believed to be associated with elevated levels of systemic inflammation [25]. This inflammation along with inflammatory mediators can lead to the development of atherosclerosis, vascular changes, and ischemic lesions. All of these can factor into depressive symptoms [26]. Martinac et al. [27] hypothesized that metabolic syndrome and depressive disorder were connected through hyperactivity of the hypothalamicpituitary- adrenal (HPA) axis and changes in the immune system [27]. More research is needed to further understand this theory. The most common chronic diseases we found in our study were HTN, CHF, diabetes, and kidney disease. In addition, we found that patients with the coexisting chronic diseases mentioned above reported lower HRQoL scores in both the physical and mental domains. Previous studies confirmed our analyses of comorbidities and deterioration of HRQoL [28]. Other studies have looked at quality of life in people with diabetes and other chronic conditions including: HTN, CHF, and heart disease. One study looked at patients with diabetes who reported the most role limitations due to physical health and current health perception [29].

A study conducted in Norway, which included patients with both types of diabetes found that patients reported lower wellbeing and more illness-related absences from work, less satisfaction with their leisure time, and fewer social contacts than subjects without chronic diseases [30]. In another study based in the U.S., hypertensive patients reported worse mental and emotional outcomes. This study suggests that a chronic disease such as HTN, requires multiple medication therapy, which could worsen the patient’s health perception and adherence [31]. These studies didn’t evaluate the level of complications accompanying each disease because that can be associated with poorer quality of life. At the same time, most of those studies do not include patients’ characteristics and generate prevalence in which quality of life aspects take place. Similar research is also needed for hyperlipidemia patients. We need to look at the stage of hyperlipidemia with respect to patient characteristics. This could assist in targeting specific interventions at improving HRQoL among hyperlipidemia patients.

Education is often used to define socioeconomic status and improved health outcomes, and has a direct positive relationship with HRQoL [32]. Educated individuals may be more able to understand information about their disease state and therefore can make better lifestyle choices. They are able to understand the benefits of treatment and the complications that could result from not following their physician’s order. Less educated patients have less access to health education which can prevent improvement of their disease states [33]. However, more educated individuals may tend to overthink their disease state, for which reason we found a significantly higher MCS for high school graduates. For the MCS, less educated patients scored higher demonstrating overall better mental health than their more educated counterparts. Lower income patients have a decreased ability to afford their therapy, healthy food options, and transportation for access to health care. Middle class patients may be unable to afford private insurance and unable to qualify for federal public insurance.

Age is considered an important predictor of HRQoL since many physical, mental, and psychological changes result from the aging process. As people age, there is a decline in vision, hearing, immune system function, and musculoskeletal strength and function. In addition, people are more likely to experience comorbidities which can significantly impact HRQoL [34]. According to our study, marital status was a factor in the mental health of hyperlipidemia patients. Those having emotional and social support from their spouses have better mental score. The finding is consistent with a study number of studies which reveals that married patients who were cohabiting with their partner had higher scores compared to those who were not residing with their partner [35]. Income, education, and perceived health status are essential to improve HRQoL for hyperlipidemia patients [36]. Likewise, improvement in public insurance is needed for betterment of mental and physical aspects of HRQoL among its holders, similar to private insurance holders. Many Hispanic people living in the U.S. are immigrants and are ineligible for government insurance.

MEPS provides the most complete data of cost and use of healthcare. It is monitored by the AHRQ and is updated annually [37]. Our study includes a large population size and a broader range of age groups participating in the study. Large population size can help to eliminate bias, while a broad age range allows us to understand differences in patient characteristics. An additional strength of the study was the use of the Charlson comorbidity index. This allowed us to input our data into multiple regression analyses to fit the SF-12, PCS, and MCS scores for all measured comorbidities and selected characteristics. However, the study has some limitations. In the datasource MEPS, databases are preselected and not considered a well representation of all U.S. states. The datasets selected for each panel of the MEPS HC is a subsample from the previous year’s National health Interview Survey (NHIS) data.

The NHIS is conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics and is a sampling frame that provides a nationally representative sample of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population. This sample set of the population tends to reflect and oversample Black and Hispanic populations [38]. MEPS data can be biased based on the patients answering the survey questions and how they answer these questions [37].

Conclusion

Chronic conditions that require medication treatment for longer periods of time can adversely affect the patient’s quality of life. Our study showed lower quality of life in U.S. Hispanics with hyperlipidemia and other chronic co-morbid conditions. There is a need for additional research to be conducted in minority populations to understand the impact of other chronic disease conditions such as diabetes, HTN and CHF and related comorbidities on their quality of life.

References

- Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Robert J Adams, Jarett D Berry, et al. (2011) Heart disease and stroke statistics--2011 update: a report from the American Heart Association. [published correction appears in Circulation 124(16): e426]. Circulation. 2011;123(4): e18-e209.

- Farley TA, Dalal MA, Mostashari F, Frieden TR (2010) Deaths preventable in the U.S. by improvements in use of clinical preventive services. Am J Prev Med 38(6): 600-609.

- Heidenreich PA, Trogdon JG, Khavjou OA, Javed Butler, Kathleen Dracup, et al. (2011) Forecasting the future of cardiovascular disease in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 123(8): 933-944.

- (1995) The World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment (WHOQOL): position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc Sci Med 41(10): 1403-1409.

- Ferrans CE (2004) Definitions and conceptual models of quality of life. Outcomes Assessment in Cancer 14-30.

- Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, et al. (2008) Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2018 Update: A Report from the American Heart Association [published correction appears in Circulation. 2018 Mar 20;137(12): e493]. Circulation 137(12): e67-e492.

- Shah BM, Mezzio DJ, Ho J, Ip EJ. (2015) Association of ABC (HbA1c, blood pressure, LDL-cholesterol) goal attainment with depression and health-related quality of life among adults with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Complications 29(6): 794-800.

- Writing Group Members, Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Alan S Go, Donna K Arnett, et al. (2016) Executive Summary: Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2016 Update: A Report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 133(4): 447-454.

- Boekholdt SM, Arsenault BJ, Mora S, Terje R Pedersen, John C LaRosa, et al. (2012) Association of LDL cholesterol, non-HDL cholesterol, and apolipoprotein B levels with risk of cardiovascular events among patients treated with statins: a meta-analysis [published correction appears in JAMA. 2012 Apr 25;307(16):1694] [published correction appears in JAMA. 2012;9;307(18):1915]. JAMA. 2012;307(12): 1302-1309.

- Sniderman AD, Williams K, Contois JH, Matthew J McQueen, Jacqueline de Graaf, et al. (2011) A meta-analysis of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and apolipoprotein B as markers of cardiovascular risk. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 4(3): 337-345.

- Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, C Noel Bairey Merz, Conrad B Blum, et al. (2015) 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines [published correction appears in J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;1;63(25 Pt 3024-3025] [published correction appears in J Am Coll Cardiol; 22;66(24):2812]. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 Pt B): 2889-2934.

- Surveillance report 2018 – Cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and reduction, including lipid modification (2014) NICE guideline CG181. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK); January 25, 2018.

- Pekkanen J, Linn S, Heiss G, C M Suchindran, A Leon, et al. (1990) Ten-year mortality from cardiovascular disease in relation to cholesterol level among men with and without preexisting cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med 322(24): 1700-1707.

- Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, Deswal A, Sandra B Dunbar, Gary S Francis, et al. (2016) Contributory Risk and Management of Comorbidities of Hypertension, Obesity, Diabetes Mellitus, Hyperlipidemia, and Metabolic Syndrome in Chronic Heart Failure: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 134(23): e535-e578.

- Hyttinen L, Strandberg TE, Strandberg AY, Salomaa VV, Pitkälä KH, et al. (2011) Effect of cholesterol on mortality and quality of life up to a 46-year follow-up. Am J Cardiol 108(5) :677-681.

- Einvik G, Ekeberg O, Lavik JG, Ellingsen I, Klemsdal TO, et al. (2010) The influence of long-term awareness of hyperlipidemia and of 3 years of dietary counseling on depression, anxiety, and quality of life. J Psychosom Res 68(6): 567-572.

- Akioyamen LE, Genest J, Shan SD, Inibhunu H, Chu A, et al. (2018) Anxiety, depression, and health-related quality of life in heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res 109: 32-43.

- (2015) Hyperlipidemia ICD 9 Code. Published July 7, 2014. Accessed December 2, 2020.

- Ratanawongsa N, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Couper MP, Van Hoewyk J, Powe NR, et al. (2010) Race, ethnicity, and shared decision making for hyperlipidemia and hypertension treatment: the DECISIONS survey. Med Decis Making 30(5 Suppl): 65S-76S.

- Smith AG, Singleton JR (2013) Obesity and hyperlipidemia are risk factors for early diabetic neuropathy. J Diabetes Complications 27(5): 436-442.

- Shih HJ, Huang CJ, Lin JA, Kao MC, Fan YC, et al. (2018) Hyperlipidemia is associated with an increased risk of clinical benign prostatic hyperplasia. Prostate 78(2): 113-120.

- Vega WA, Rodriguez MA, Gruskin E (2009) Health disparities in the Latino population. Epidemiol 31: 99-112.

- Riley E, Chang J, Park C, Kim S, Song I, et al. (2019) Hypertension and Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL): Evidence from the US Hispanic Population. Clin Drug Investig 39(9): 899-908.

- Sullivan PW, Ghushchyan VH, Ben-Joseph R (2008) The impact of obesity on diabetes, hyperlipidemia and hypertension in the United States. Qual Life Res 17(8): 1063-1071.

- Tietge UJ (2014) Hyperlipidemia and cardiovascular disease: inflammation, dyslipidemia, and atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol 25(1): 94-95.

- Alexopoulos GS, Meyers BS, Young RC, Campbell S, Silbersweig D, et al. (1997) Vascular depression' hypothesis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 54(10): 915-922.

- Martinac M, Pehar D, Karlović D, Babić D, Marcinko D, et al. (2014) Metabolic syndrome, activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and inflammatory mediators in depressive disorder. Acta Clin Croat 53(1): 55-71.

- Zygmuntowicz M, Owczarek A, Elibol A, Chudek J (2012) Comorbidities and the quality of life in hypertensive patients. Pol Arch Med Wewn 122(7-8): 333-340.

- Stewart AL, Greenfield S, Hays RD, et al. (1989) Functional status and well-being of patients with chronic conditions. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. [published correction appears in JAMA 1989 Nov 10;262(18):2542]. JAMA. 262(7): 907-913.

- Naess S, Midthjell K, Moum T, Sørensen T, Tambs K, et al. (1995) Diabetes mellitus and psychological well-being. Results of the Nord-Trøndelag health survey. Scand J Soc Med 23(3): 179-188.

- Stewart AL, Hays RD, Wells KB, Rogers WH, Spritzer KL, et al. (1994) Long-term functioning and well-being outcomes associated with physical activity and exercise in patients with chronic conditions in the Medical Outcomes Study. J Clin Epidemiol 47(7): 719-730.

- Cutler D, Lleras-Muney A (2006) Education and Health: Evaluating Theories and Evidence. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series. July 2006.

- Al-Mandhari A, Al-Zakwani I, Al-Hasni A, Al-Sumri N (2011) Assessment of perceived health status in hypertensive and diabetes mellitus patients at primary health centers in oman. Int J Prev Med 2(4): 256-263.

- Beard J, Officer A, Cassels A, Bustreo F, Worning AM, et al. (2015) World report on ageing and health 2015. World Health Organization. Published June 12, 2017. Accessed December 4, 2020.

- Carvalho MV, Siqueira LB, Sousa AL, Jardim PC (2013) The influence of hypertension on quality of life. Arq Bras Cardiol 100(2): 164-174.

- Ghimire S, Pradhananga P, Baral BK, Shrestha N (2017) Factors Associated with Health-Related Quality of Life among Hypertensive Patients in Kathmandu, Nepal. Front Cardiovasc Med 4: 69.

- (2010) Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Background. Published September 2010. Accessed December 4, 2020.

- Ezzati-Rice TM, Rohde F, Greenblatt J (2020) Methodology Report #22: Sample Design of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household Component 1998-2007.

Research Article

Research Article