Introduction

Pterional craniotomy is a method which provides wide access to the skull base. This method is considered crucial in neurosurgery, however this approach has a drawback, which is the need to perform a complete dissection of the temporal muscle. This leads to a risk of blemishes and functional alterations concerning chewing: this functional deficit is generally due to damage of the frontal branch of the Facial nerve and to the atrophy of the temporalis muscle [1-3].

The advantages of this method are:

1. Reduced surgery time

2. Less trauma of tissues around the lesion

3. More favorable postoperative course

4. Less hospitalization time

5. Lower costs and

6. Better aesthetic and functional results [4-6].

A variation to the classic pterional approach was proposed by J. Hernesniemi with the technique of the „lateral supraorbital approach”: it represents an alternative to the classic pterional approach with different indications and different operative advantages [5]. The greatest challenge of modern neurosurgery is to find new strategies that reduce invasiveness without compromising visibility and accessibility to the operating field: the pterional approach, in light of these considerations, represents the gold standard for surgeon-friendly neurosurgery and patientfriendly.

Surgical Procedure

Head Position

The patient is in supine position. The head is directed about 20 degrees downwards, elevated and rotated according to the position of the aneurysm or of the lesion to be approached: in positioning the head it is necessary to avoid that the contraction of the cervical muscles create an obstacle to the regular cerebral blood flow along the main pathways venous.

Skin Incision and Dissection of Temporalis Muscle

After the incision of the skin, fascia temporalis and temporalis muscle must be incised too using a scalpel, muscles have to be spaced apart together with the skin to avoid injuries to the Frontal and Facial nerve. It is important to save the Temporalis Superficialis artery because it can be used for a intracranial or extracranial vascular bypass.

Craniotomy

On the Temporalis bone two holes have to be done to gain the access: the first hole is posterior, it is done above the zygomatic arch, the second one, also called the “key hole”, it is brought forward up to one and a half cm on the frontal bone then with a curvilinear course we cross the superior temporal line and following the cutaneous edge we reach the posterior limit of the bone flap. The following phase of the osteotomy is done with a surgical drill, it creates a bloodless access to the skull base, this method also breaks part of the lesser wing of the Sphenoid bone. The incision of the Dura Mater is done with a semicircular incision around the Lateral Sulcus; then the first meninge can be spaced apart to gain the access to the Arachnoid [1,3,7]. In the pterional approach the risk of injuring the temporal branch of the Facialis nerve is high, this leads to the possibility of causing iatrogenic aesthetic-functional type damage, such as alteration of the tone of the Frontalis muscle and of the Orbicularis muscle: these two branches are particularly evident following the subgaleal pterional approach, but the risk is reduced if the temporal muscle is preserved together with the galeal fascia. The temporal branch of the facial nerve crosses the zygomatic process, reaching the frontal muscle: if the pterional access incision follows the reference of the temporal fascia, preserving the body of the temporal muscle, injuries to the branches of the facial nerve, that carry the innervation to the Frontal muscles, are avoided [8- 12]. The aim of the work is to verify the clinical, morphological and functional implications of the pterional approach in pathologies with neurosurgical indication; specifically, we want to investigate whether the surgical umlaut envisaged by this approach should have a full-thickness linear course, or multiple thicknesses following the planes of each fascia; finally you want to evaluate if the umlaut is safer with the cold blade scalpel or with the monopolar? [13-17].

Materials and Methods

Between 2008 and 2015, the authors retrospectively selected 876 patients, treated with the pterional access technique: the pathologies that required neurosurgery were intracranial aneurysms, meningiomas of the anterior and middle cranial fossa, and some types of glioma arising in the temporo-frontal area. The inclusion criteria excluded patients with pain, inflammation or infections in the region of the surgical site, patients who had reoperations in the same area, patients who had craniofacial trauma, and patients who required surgical access so broad that affect the temporal muscle, since this muscle could have an abnormal scarring outcome, predisposing the region to abnormal and deforming musculoskeletal stresses. At the end of the sample selection phase, 656 patients were included in the retrospective study.

Patients have been evaluated by the maxillofacial surgeon and by the baseline neurosurgeon (T0) before the surgery and during the post- surgery check ups. (T1-2-3-4).

The authors performed functional tests to evaluate the following parameters:

1. Functionality of the V and VII Cranial nerve,

2. Postoperative pain assessed by the VAS (visual analog scale),

3. Width of the mouth opening with reference to the interincisal distance,

4. Amplitude of lateral movements of the mandible,

5. Tone and symmetry of the masticatory muscles [14].

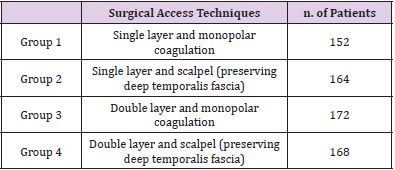

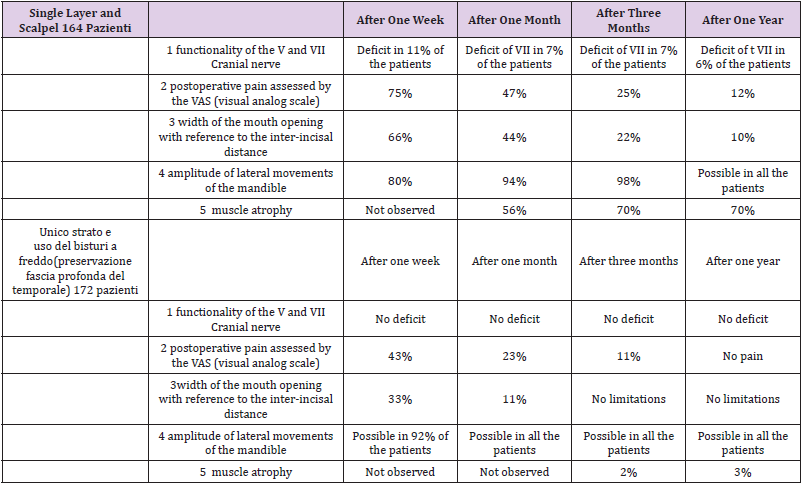

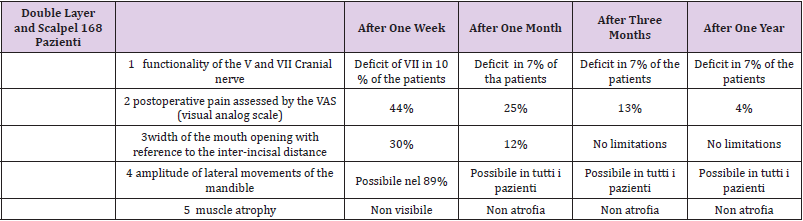

Data have been recorded at baseline (T0), one week after surgery (T1), after one month (T2), after three months (T3) after 12 months (T4). The surgical technique used was different for the different types of pathology treated, however, only those patients who had surgical access with the pteral access method were selected. Patients have been divided in 4 groups. We obtained the following results:(Tables 1-4).

Results

From the analysis of our case series we found that there are different clinical implications depending on the group analyzed and the parameters evaluated. Early postoperative complications were evident in the chewing function with painful-dysfunctional symptoms in the temporal and preauricular region, with evident difficulty in chewing: this dysfunction decreased in surgical protocols which required less dissection of the planes around the temporal muscle; this more conservative approach led to a reduction in the incidence of contractures of the temporal muscle, decreased postoperative edema and improved the post-surgical course in general. A further criticality highlighted was the presence, following pterional surgery, of sites with reduced mechanical resistance to the Frontalis muscle, caused by the opening of the muscle on two planes, this exposed the branches of the Facial nerve to injuries and dysfunctions. These branches on these planes run towards the frontal muscle. Late complications affecting the masticatory function are manifested mainly in cases in which hypotrophy of the temporal muscle is highlighted: this occurrence was mainly associated with the use of surgery with monopolar scalpel and the failure to preserve the deep fascia of the temporal muscle, limiting thus the ability to open the mouth and placing the anatomical conditions to result in dimorphisms of high aesthetic value [13,14,16-19].

Conclusion

From the literature examined, and from a careful analysis of our cases, we can deduce that the best way to dissect the temporal muscle, in the pterional approach, is to incise it together with the skin with a full thickness flap, without detaching the superficial muscle fascia from the subcutaneous plane in order to preserve the peripheral nerve branches that innervate the Frontal muscles. This approach will reduce the risk of alterations in the facial expression, function and sensitivity of the maxillofacial area in treated patients. Finally, an important indication is to preserve the internal fascia of the temporal muscle, detaching it with a blade: in fact, the cases treated with monopolar coagulation have reported in the long term important hypotrophies associated with aesthetic-functional deficits, with serious repercussions on the chewing capacity.

References

- Chaddad-Neto F, Filho JMC, Dória-Netto HL, Faria MH, Ribas GC, et al. (2012) The pterional craniotomy: tips and tricks. Arq Neuro-Psiquiatr 70(9): 727-732.

- McLaughlin N, Cutler A, Martin NA (2013) Technical nuances of temporal muscle dissection and reconstruction for the pterional keyhole craniotomy. J Neurosurg 118(2): 309-314.

- Wen HT, de Oliveira E, Tedeshi H, Antrade FC Jr, Rhoton AL Jr (2001) The Pterional Approach: Surgical Anatomy, Operative Technique, and Rationale. Operative Techiques in Neurosurgery 4(2): 60-72.

- Evans T Johns Hopkins (2012) The frontotemporal ("pterional") approach: an historical perspective. Neurosurgery 71(2): 481-491.

- Hernesniemi J, Ishii K, Niemela M, Smrcka M, Kivipelto L, et al. (2005) Lateral supraorbital approach as an alternative to the classical pterional approach Acta Neurochir 94: 17-21.

- Altay T, Couldwell WT (2012) The frontotemporal (pterional) approach: an historical perspective. Neurosurgery 71(2): 481-491.

- Yaşargil MG (1984) Microneurosurgery. Thieme Stratton New York pp. 215-234.

- Pekar L, Bláha M, Schwab J, Melechovský D (2004) Craniotomy and the temporal branch of the facial nerve. Rozhl Chir 83(5): 205-208.

- Yaşargil MG, Reichman MV, Kubik S (1987) Preservation of the frontotemporal branch of the facial nerve using the interfascial temporalis flap for pterional craniotomy. Technical article. J Neurosurg 67(3): 463-466.

- Poblete T, Jiang X, Komune N, Matsushima K, Rhoton AL Jr (2015) Preservation of the nerves to the frontalis muscle during pterional craniotomy. J Neurosurg 122(3-6): 1-9.

- Coscarella E, Vishteh AG, Spetzler RF, Seoane E, Zabramski JM (2000) Subfascial and submuscular methods of temporal muscle dissection and their relationship to the frontal branch of the facial nerve. Technical note. J Neurosurg 92(5): 877-880.

- Gosain AK (1995) Surgical anatomy of the facial nerve. Clin Plast Surg 22(2): 241-251.

- Matsumoto K, Akagi K, Abekura M, Ohkawa M, Tasaki O, et al. (2001) Cosmetic and functional reconstruction achieved using a split myofascial bone flap for pterional craniotomy. Technical note. J Neurosurg 94(4): 667-670.

- De Andrade Júnior FC, De Andrade FC, De Araujo Filho CM, Carcagnolo Filho J (1998) Dysfunction of the temporalis muscle after pterional craniotomy for intracranial aneurysms. Comparative, prospective and randomized study of one flap versus two flaps dieresis. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 56(2): 200-205.

- Bowles AP Jr (1999) Reconstruction of the temporalis muscle for pterional and cranio-orbital craniotomies. Surg Neurol 52(5): 524-529.

- Spetzler RF, Lee KS (1990) Reconstruction of the temporalis muscle for the pterional craniotomy. Technical note. J Neurosurg 73(4): 636-637.

- Zager EL, Del Vecchio DA, Bartlett SP (1993) Temporal muscle microfixation in pterional craniotomies. Technical note. J Neurosurg 79(6): 946-947.

- Miyazawa T (1998) Less invasive reconstruction of the temporalis muscle for pterional craniotomy: modified procedures. Surg Neurol 50(4): 347-351.

- Welling LC, Figueiredo EG, Wen HT, Gomes MQ, Bor-Seng-Shu E, et al. (2015) Prospective randomized study comparing clinical, functional, and aesthetic results of minipterional and classic pterional craniotomies. J Neurosurg 122(5): 1012-1019.

Research Article

Research Article