Abstract

Many women in Bangladesh terminate their pregnancy either by menstrual regulation (MR) or through abortion. Government policy doesn’t recognize abortion; but there exists a policy for MR, permitting termination of unwanted pregnancy up to 10 weeks from the last menstrual period. But access to safe MR is limited—unqualified and untrained providers mostly perform termination of pregnancy, creating unsafe abortion one among the leading causes of maternal deaths in Bangladesh. So, to cut back maternal mortality and morbidity within the country, some initiative was launched. The aim was to enhance knowledge of and access to quality MR services for the prevention of unsafe abortion and unsafe MR. the current study will examine health seeking behavior and attitudes towards MR of MR clients/patients in intervention and control areas. Findings suggest that overall respondents within the intervention area are far better off in terms of awareness regarding timeline of safe MR (88% of the MR clients) compared to their control group counterparts (74%), Different service providers have played a vital role in promoting safe MR within their respective working areas in the aspects of awareness creation, standard guideline on MR, enabling environment, and rights-based approach. However, there still remains scope to enhance quality of care.

Keywords: Menstrual Regulation; Family Planning; Unwanted Pregnancy

Introduction

Menstrual regulation (MR) is defined as “An interim method of establishing non- pregnancy for a woman who is at risk of being pregnant, whether or not she is pregnant in fact” [1-3]. On the other hand, Abortion is defined as the interruption or termination of pregnancy after the implantation of the blast cyst in the endometrium and before the resulting fetus has attained viability. Induced abortions are caused by deliberate interference, initiated voluntarily with the intention to terminate a pregnancy; all other abortions are called spontaneous abortion [4]. Bangladesh is unique in South Asia in making menstrual regulation (MR) services available to women at the community level. Menstrual regulation contains evacuation of the uterus by vacuum aspiration within 6-10 weeks of a missed menstrual period. Although abortion is forbidden in Bangladesh except to save a woman’s life (derived from the Penal Code of India 1860 and the British Offences against the Person Act 1861), menstrual regulation is not prohibited as it is considered to be an “interim method to establish a state of non- pregnancy in a woman who is at risk of being pregnant”.

Hence, it is regularly done without a pregnancy test. Under the Bangladesh Penal Code of 1860, abortion is permissible only to protect the life of a woman. In all other situations, abortionself- induced or otherwise-is a criminal offense punishable by imprisonment, fines or both. Menstrual regulation (MR)-officially recognized as an interim method for creating non-pregnancyhas been available free of charge in the government’s family planning program as a public health measure since 1979 [5]. One of the important goals of Health, Nutriton and Population Sector Programme (HNPSP) of the government of Bangladesh has been to improve the health and family welfare status of the most vulnerable groups- women, children and the poor. Bangladesh has achieved significant progress in health and population indicators over the last few years (due to increased access to health and FP services) through a combination of facility level, community and household level service provision strategies. The fertility transition is already underway in the country and the success of the immunization program is most impressive, including reductions in infant and child mortality.

The contraceptive prevalence rate has already reached more than 50% level. On an average, women in Bangladesh now give birth to only 2.3 children as compared to 6.3 children in the mid 1970s. More than 50 per cent of married couples of reproductive age have been protected by modern contraception now as compared to only 8 per cent in the early seventies. The expectation of life at birth for both sexes has increased from about 45 years in the mid 1970s to 66.7 years in 2008. These are some of the notable changes that have occurred in the demographic profile of Bangladesh. It is remarkable that despite adverse socio-economic environment, commendable success in reproductive and child health has been achieved over the period of three decades. The infant mortality rate showed a steady decline from 150 deaths per 1000 live births in 1973 to 94 in 1991, 47 by 2007 [6] and 43 in 2011 [7], while the under five-mortality rate declined from around 260 deaths per 1000 live births to only 53 over the same period (NIPORT 2011). Immunization coverage at the age of 12 months increased from as low as 54% in 1990 to 82.5% in 2011 and the country is expecting to attain polio-free status very soon [8].

Objectives

BICOM Bioresonance Device

The main purpose of the present study is to assess whether and to what extent the interventions of the some service providers that perform MR services have an impact in terms of increasing awareness regarding MR and increasing knowledge on safe timeline and appropriate place for performing MR and to what extent has the intervention been effective in increasing the social awareness regarding MR and abortion issues and removing misconceptions related to MR. It will also examine quality and utilization of MR services of service providers including pre- and post-counseling and barriers in accessing services. The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 3 provides literature review, section 4 provides methodology, section 5 describes knowledge, attitudes, health seeking behavior and health service facilities of MR client regarding FP and MR and section 6 will discuss results and findings.

Literature Review

Status of Maternal Mortality

There are two indicators for monitoring the reduction of maternal mortality – maternal mortality ratio (MMR) and proportion of births attended by skilled health personnel. In 2006 the estimated MMR of Bangladesh was 290 (UNFPA), but according to BBS, the MMR is 315 for 2007 estimated from the Sample Vital Registration System (BBS, 2008). According to government statistics, maternal deaths fell by at least 60% from 1990 to 2010– 2011 [9]. Further evidence in this regard comes from the two official government studies of maternal mortality (Bangladesh Maternal Mortality Surveys, or BMMS), which were conducted in 2001 and 2010 [10]. Their results offer further evidence of this steep decline: a drop in maternal mortality of two-fifths in less than one decade. In 2011, MMR was 194. Maternal mortality has dropped considerably in Bangladesh over the past few decades. Some of that declinethough exactly how much cannot be quantified-is likely attributable to the country’s menstrual regulation (MR) program, which allows women to establish non-pregnancy safely after a missed period and thus avoid recourse to unsafe abortion [11].

According to [11] Bangladesh has succeeded in reducing deaths during pregnancy and childbirth by improving access to maternal health care and lowering fertility, especially births that pose above-average health risks (e.g., births occurring to highparity women). What makes the country unique, however, is the potential contribution of an authorized procedure—known as menstrual regulation, or MR-to “establish non- pregnancy” after a missed period [2]. A national level survey conducted during 1978- 79 found that complications from unsafe abortion played a major role in 26% of maternal deaths [12]. Similarly, a study of rural areas conducted during the 1980s found that the proportion of maternal deaths attributable to abortion was 15% [13]. However, there has been substantial improvement in this regard over the last two decades as will be clear from the following. Findings from first national maternal mortality survey of 2001 (NIPORT 2001) found a substantially lower proportion of maternal deaths attributable to abortion-only 5% of maternal deaths were related to induced abortion [14].

The 2011 BMMS found an even smaller percentage, merely 1% of maternal deaths were attributable to abortion during 2008– 2010. If this last estimate is accurate, it points to a steep decline in the proportion of maternal deaths due to unsafe abortion [10]. However, it needs to be emphasized that the various surveys used different methodologies, some methodologies were less rigorous than others. Again, surveys associated to maternal mortality in general, and of abortion related mortality in particular, are likely to suffer from recall lapse and high levels of under-reporting [9]. It is to note that Bangladesh is a moderate Muslim country with some cultural values of conservative nature. Living together with partner, extramarital sex and getting children without being married is against the norm of the society. Such women are socially excluded and their children cannot be reared as other children in the society. Women therefore try to hide their relationship with their partner, and in case of pregnancy outside wedlock, they try to abort the child in secrecy. In this backdrop, MR is considered as a tool to hide the ‘sin’ of secret sexual relations, and therefore is socially unacceptable in Bangladesh.

MR is also considered as a sin from religious point of view. ‘Children’ are considered to be ‘gift of God’ and any harm to them is not religiously acceptable. Moreover, there remains some misconception about the health hazards associated with MR, which makes it unpopular among general people. Social, cultural and religious norms along with some misconception make MR a sensitive issue in Bangladesh.

The Marie Stopes Clinic Society (MSCS)

The Marie Stopes Clinic Society has been providing a wide range of Sexual and Reproductive Health (SRH) services including MR in Bangladesh since 1988. With the support of the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands (EKN), the following districts have been covered: Narayangonj of Dhaka division; Maulvibazar of Sylhet division; Feni under Chittagong division, and Sherpur under Dhaka division. The main goal of MSCS was to increase awareness on prevention of unwanted pregnancy and MR services and to improve quality of safe MR services. The community awareness strategy used by MSCS involved different sectors of the community: NGO field workers, male key decision makers, locally elected male and female leaders, female community support groups (FCSG), micro-credit NGO field workers, college and schoolteachers etc.

The Family Planning Association of Bangladesh (FPAB)

The Family Planning Association of Bangladesh is a member of the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF) and has been working in Bangladesh since 1953. It is the oldest NGO in Bangladesh and provides a range of reproductive health, family planning services, including MR services. The project has been applied at six FPAB clinics in six districts: Barisal, Chittagong, Sylhet, Jhalakati, Magura and Netrokona. In order to encourage community awareness, reproductive health promoters (RHP) have been used to disseminate the key messages to the community.

The Menstrual Regulation (MR) Program in Bangladesh

The exceptional contribution of MR to women’s health care in Bangladesh dates from the early 1970s. During the early 1970s, the government of Bangladesh introduced MR services in a few urban family planning clinics and district hospitals under the guidance of an expert team from Bangladesh, India, the United Kingdom, and the United States [15,16]. In 1978, the Pathfinder Fund initiated and funded the Menstrual Regulation Training and Service Programs (MRTSP) in seven government medical colleges located throughout the country, two district hospitals, and one family planning clinic. This was the start of what was to become the Menstrual Regulation Training and Services Program (MRTSP). MR services were introduced in Bangladesh in 1974 on a small scale to evaluate the feasibility of providing them nationally; in 1979, a training program was initiated in seven medical college hospitals and two district hospitals [17]. In 1979 MR was legalized and incorporated into the National Family Planning Program. The government stated unequivocally that MR services were to be available in all government hospitals and health and family planning complexes at the district and upazila levels.

In order to promote this program the government issued a circular including MR in the national family planning program and encouraging service providers to offer service in all government hospitals and health and family planning complexes (the present day UHCs) [2]. The program was designed to train government doctors, a few private doctors, and female family planning workers (Family Welfare Visitors, or FWVs, employed at upazila/union level health posts) in MR techniques. Menstrual regulation (MR) is extensively available in Bangladesh through public, NGO and private sector services, even though abortion is illegal except to save a woman’s life. For more than two decades, the MR programme was run as a vertical programme. However, in1998the Government of Bangladesh introduced the Health and Population Sector Programme (HPSP) incorporating menstrual regulation into the essential services package (ESP). MR is allowed up to 10 weeks after the last menstrual period (LMP) if performed by a physician [18].

Family Welfare Visitors (FWVs) and paramedics such as subassistant community medical officers (SACMOs) are permitted to provide MR services up to eight weeks after the LMP. The mainly female FWVs have a minimum of 10 years of schooling and obtain at least 18 months’ training in reproductive and child health services, including training in how to perform [19]. If MRs were universally accessible in Bangladesh, they could greatly decrease the potential need for women to have an unsafe clandestine abortion. Currently, many women who would want to get an MR face barriers to obtaining one; many of them resort to unsafe abortion as a result. Because induced abortions are legally regulated in Bangladesh, they are often practiced clandestinely in unhygienic settings, performed by untrained providers, or both. By avoiding unsafe abortions and their associated health complications, MR could have a positive impact on women’s health and survival [20].

Menstrual Regulation (MR) Services

The original impetus for introducing MR services came from scientists, government and international leadership. Support for provision of this reproductive health service is broad based and includes these as well as other stake-holders such as service providers and women’s rights organizations [21]. Nevertheless, studies have suggested that there is room and need for improvement in access to quality MR services. In addition, a recent review of the MR program has argued that it has been marginalized within overall health policy in Bangladesh over the last decade [19]. A government authorization rule controls MR [2], which is generally done with manual vacuum aspiration (MVA). The rule provides specific guidance for the provision of MR services, covering the kinds of providers who can deal the service, namely, doctors, family welfare visitors (FWVs) and paramedics (include providers such as Sub-Assistant Community Medical Officer-SACMO, and medical assistants); the situation of service provision, either outpatient or inpatient; and the maximum number of weeks allowed since the last menstrual period (LMP).

Although MR is allowed up to eight weeks after LMP when performed by FWVs and paramedics, and up to 10 weeks after LMP when implemented by a physician, providers occasionally perform the procedure later as well [20-28]. Currently MR is widely practiced throughout the country and is available at all tiers, from district and higher level hospitals down to union (consisting of 15 -20 villages) level health centres. It is also available in a limited number of NGO clinics and in the private sector. Both doctors and paramedics provide MR, but at the union level, female paramedics are the only trained providers. Maternal health services in Bangladesh are provided at community and facility levels through a national network of public-sector facilities, ranging from Union Health and Family Welfare Centres (UH&FWCs), which are rural clinics staffed by FWVs and paramedics, to larger clinics called Mother and Child Welfare Centres (MCWCs) and Upazila Health Complexes (UHCs), and district hospitals. FWVs are essential actors in the provision of MR services, especially in countryside areas. At the community level, female family welfare assistants (FWAs) mainly deliver family planning services and some maternal health services to rural women.

Data and Methodology

Study Design

As FPAB and MSCS are crucial service providers for performing MR services, the present study is limited to project areas of Family Planning Association of Bangladesh (FPAB) and Marie Stopes Clinic Society (MSCS) being implemented in North-east region i.e. Sylhet division – FPAB in Sylhet district and MSCS in Maulvibazar district. The catchment area of the FPAB project in Sylhet district is the periurban area of the city of Sylhet and the surrounding rural areas (covering Sylhet Sadar Upazila and South Surma Upazila), while the catchment area of the Marie Stopes project in Maulvibazar is the whole of Maulvibaza district. Two upazilas from Sylhet and from Maulvibazar each were covered, which are considered as ‘intervention’ area. For comparison purposes, two upazilas from Habigonj district (where FPAB and MSCS are absent) are selected as ‘control area’.

Selection of Respondents for Survey

The survey covered 200 MR clients in project/intervention area and 100 MR clients in control area. In each district, the sample comprised one district hospital (DH), two Upazila Health Complexes (UHCs), and four Union Health and Family Welfare Centres (HFWCs). Total facilities covered included 3 District Hospitals (DHs), 6 Upazila Health Complexes (UHCs), and 12 Union Health and Family Welfare Centres (UHFWCs). In addition, FPAB clinic in Sylhet and MSCS clinic in Maulvibazar have also been covered.

Qualitative Data Collection Methods

The study also observed the role of service providers to measure their knowledge on job responsibility, thoughts on the quality of MR services, extent of follow-up services and so on. In-depth interviews were conducted with managers in health facilities and health care providers at different levels. Key Informant Interview (KII) of program managers included: Civil Surgeons at the district hospital (DH) and program managers/project directors of FPAB/ MSCS, Upazila Health and Family Planning Officer (UHFPO) at the Upazila Health Complex (UHC), Sub-Assistant Community Medical Officer (SACMO) at the UHFWC etc; while interview of service providers included: doctors, nurses and health assistants/ FWVs/ FWAs working at the health facilities in study locations. Information was obtained on constraints regarding hospital management and improving efficiency of service delivery, and other related aspects of quality of care. Guidelines were prepared for KIIs.

Family Planning (Fp) Practices and Health Seeking Behavior Of Menstrual Regulation (Mr) Clients

Background of the MR Clients

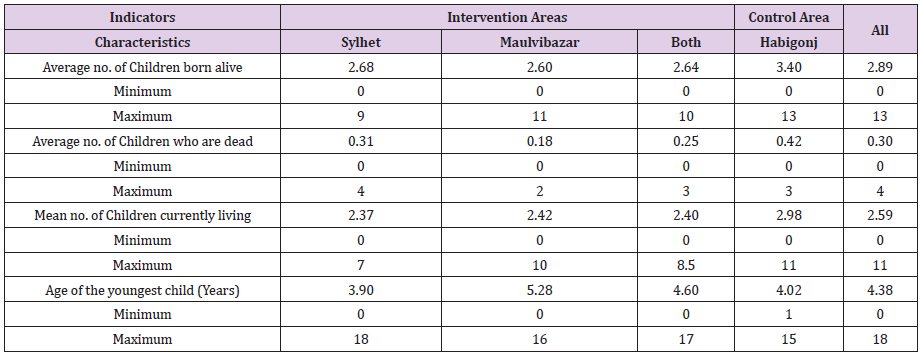

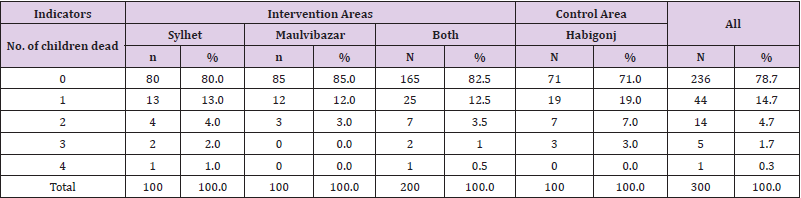

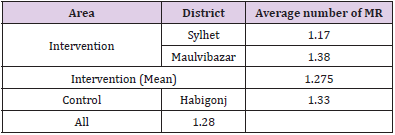

MR clients were located with the help of key informants and through field- level health workers working in the study area. Around 55% of the MR clients were aged between 21 to 30 years, while 6% were aged between 15 to 20 years. Mean age of MR clients was 29 years. Little variation was found in age distribution of MR clients between intervention and control areas. However, their level of education varied by area. The proportion of illiterate clients was higher in intervention area (31%) as compared to control area (17%). The study reveals that the average number of children born alive, children who were dead and children currently living per woman were higher in control area as compared to intervention areas (Tables 1-3).

Table 1: Percentage Distribution of MR Clients by Number of Children Born Alive and Currently Living: by Area.

Experience of MR Clients

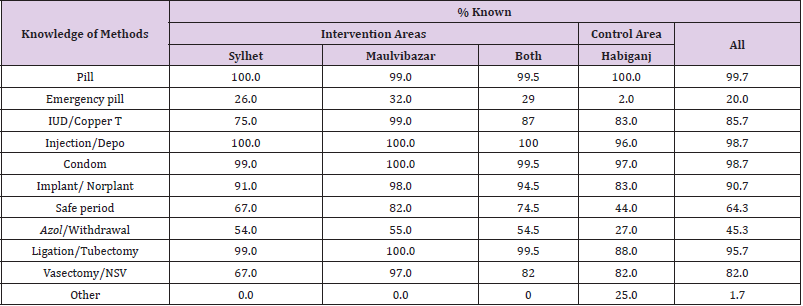

Knowledge about Family Planning Methods

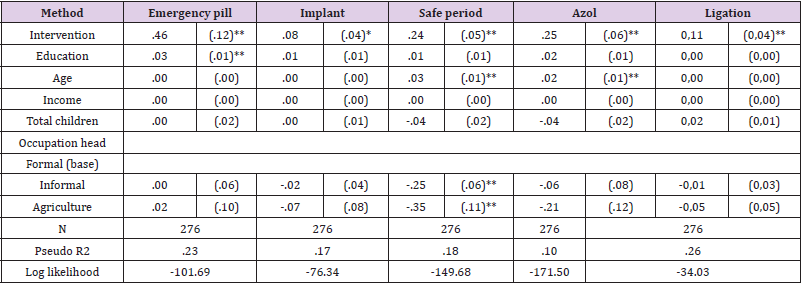

a) Family Planning Methods: Information on knowledge of family planning methods was assessed by asking respondents whether they know about specific method. The findings suggest that respondents had knowledge about different types of FP methods, including pill, injection, condom, IUD and implant/Norplant. However, the proportion of MR clients who had knowledge about emergency pill and Azol/withdrawal was considerably lower in control area as compared to intervention areas (emergency pillintervention area: 29%, control area: 2%). From logistic regression shown in Table 4, we also found some significant results. The intervention did, however, raise the knowledge of the MR clients of the emergency pill, azol/withdrawal, the safe period, ligation and the implant, from largest to smallest effect respectively.

Table 4: Knowledge about Family planning Method (Logistic regression).

Logit estimation; average marginal effects. Standard errors presented in parentheses. *p<.05; **p<.01

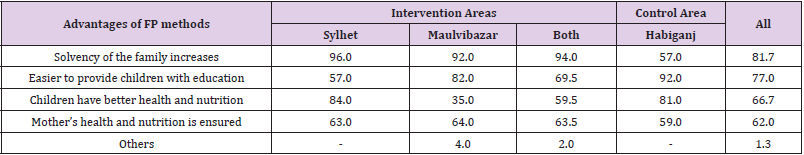

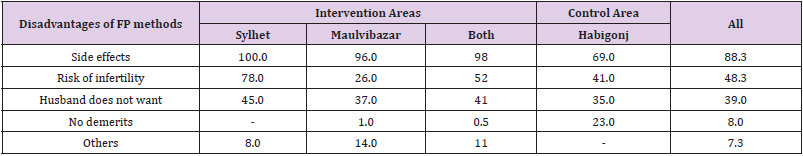

b) Advantages of FP Methods: From Table 5, the findings suggest that MR clients were aware about the advantages of using FP methods. They stated that using FP methods would enhance solvency of the family members, would help them to provide education to their children, and also would keep the mother and children healthy and nutritious. However, in the control area, the proportion of MR clients who perceived that using FP methods would ensure mother’s health and nutrition status was lower than intervention area. The perception of MR clients about disadvantages/ demerits of FP methods are outlined in (Table 6). It appears that a large proportion of MR client in intervention and control area believed that FP methods had side effects. However, 23% of respondents in Habigonj believed that FP methods had no side effects. The MR client was asked whether she or her husband is currently using any contraceptive method (at the time of the survey). It was evident that 85% (165/200) MR clients or their husbands were current users of Family Planning (FP) method in the intervention area, while the proportion was 77% (77/100) in control area. Among those who used any FP method, vast majority used pill in both the intervention and control areas.

Table 5: Percentage Distribution of MR clients by their Perceptions on Advantages of FP Methods (multiple responses): by Area.

Table 6: Percentage Distribution of MR Clients by their Perceptions Regarding Disadvantages of FP Methods (multiple responses): by Area.

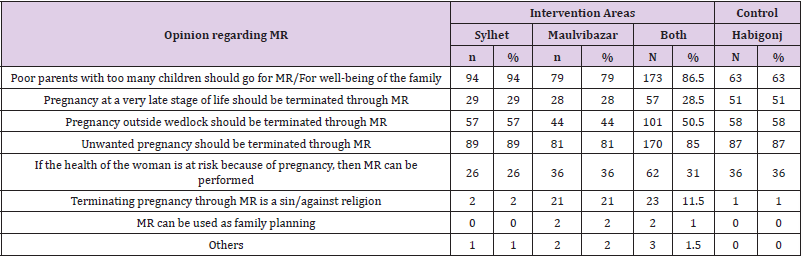

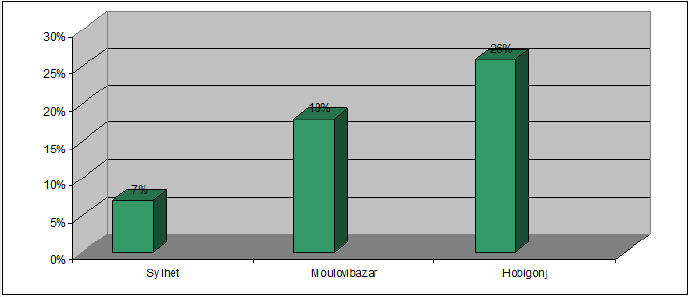

a) Knowledge about MR: The knowledge of the respondents about MR was assessed based on their awareness on this timeline of MR. It was found that 26% of the respondents in control area had incorrect knowledge on the timeline of safe MR, while the proportion was 12.5 % in intervention area (7% in Sylhet and 18% in Maulvibazar). MR clients were also asked about the reasons and advantages of doing MR. More than four-fifths (86.5%) respondents in the intervention area and 63% in the control area stated that unwanted pregnancy should be terminated through MR. Though 11.5% respondents in intervention area considered MR as a sin or against religion, the proportion was considerably lower in control area (1%) (Table 7).

Table 7: Percentage Distribution of MR Clients According to their Perceptions on Reasons/Advantages/Disadvantages of MR by Area.

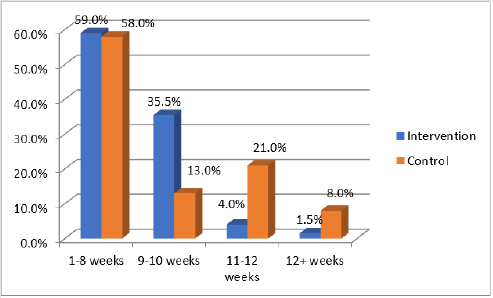

b) Timeline for MR: According to government policy in Bangladesh, the procedure of safe MR needs to be performed within eight weeks from the first day of last menstrual period (LMP) if performed by a paramedic (that is, a trained family welfare visitor) or within ten weeks from the first day of the LMP if performed by a trained medical doctor. Knowledge about timeline of MR is important for safe MR. The present study also assessed the knowledge of MR clients based on their awareness on this timeline of MR. It was found that 74% of the MR clients had correct knowledge about the timeline of safe MR in control area, while the proportion was considerably higher in intervention areas (88%). (Figure 1). The intervention has been successful in improving the MR clients’ knowledge about the timeliness of MR, ceteris paribus. However, it appears that the intervention had a significantly stronger positive effect on the MR clients.

Figure 1: Percentage Distribution of MR Clients having incorrect knowledge about the timeline of safe MR.

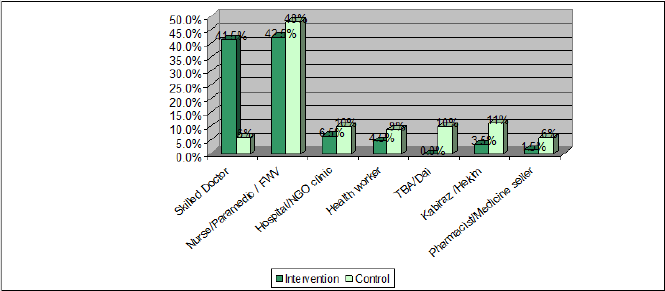

c) Assistance for MR: The present study found that in the intervention area, 41.5% of the MR was performed by skilled doctors as opposed to 6% in control area. However, MR assisted by nurse/paramedic/FWV and hospital/NGO clinic was slightly higher in control area (42.5% in the intervention area and 48% in control area). The MR assisted by Traditional Birth Assistant (TBA/ Dai) and kabiraj/hekim were also considerably high in control area (10% and 11% respectively) (Figure 2). On the whole, 90% of the MR cases in the intervention areas were performed by trained/ skilled provider, the corresponding figure was 64% in the control area. About a quarter of the MR cases (27%) in control area was performed by traditional unskilled providers like hekim/kabiraj (11%), TBA/ dai(10%), medicine seller (6%). In the intervention area, a significantly larger proportion of clients had the procedure performed by a skilled doctor than in the control area.

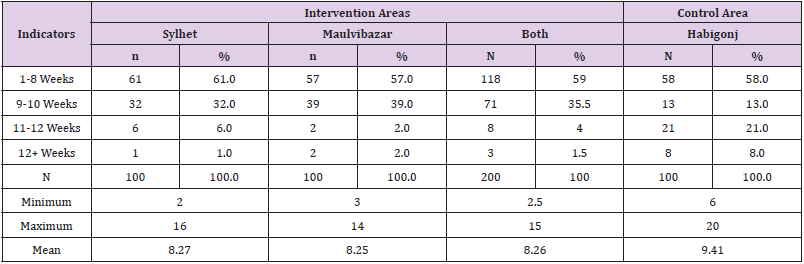

d) Duration of Pregnancy when MR was Performed: Safe MR requires maintaining safe timeline. Among the MR clients in intervention areas, 59% reported that MR was done within 8 weeks from the LMP which was 9.9% in the baseline survey. This is a good indication that the interventions of the project have been highly successful. However, 5.5% respondents in intervention areas told that their MR was performed more than 10 weeks after LMP. In control area, 29% of MR clients had the procedure performed after 10 weeks of LMP, which is a risky procedure involving life threatening consequences, and needs attention of the policy makers (Table 8 and Figure 3). Good quality of care reduces the risk of complications. Quality of care includes that clients will be informed on the procedure, that the provider is technically competent and operates in clean premises that the provider is friendly towards the client and that follow-up mechanisms are in place. Good quality of care also includes an appropriate constellation of services in case of complications.

Table 8: Percentage Distribution of MR Clients by Duration of Pregnancy (timeline) when the MR was performed: by Area.

Figure 2: Percentage Distribution of MR Clients by type of Provider Who Performed the Procedure: by Area.

Figure 3: Percentage distribution of the MR Clients according to the time line when they had the MR performed.

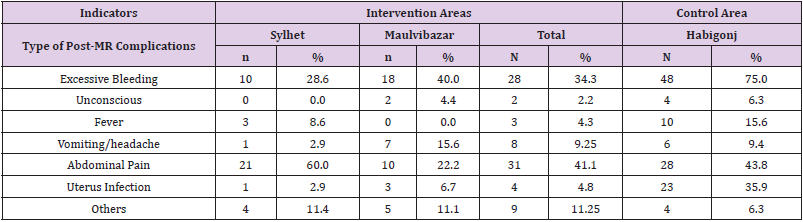

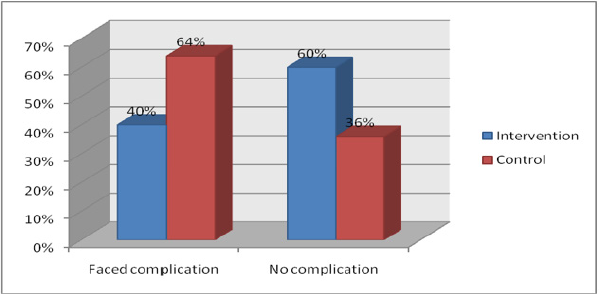

The findings suggest that in intervention areas, 40% MR clients faced complications after MR (35% in Sylhet and 45% in Maulvibazar), and the remaining 60% did not face any post MR complication. However, the proportion of respondents who faced complications after MR was markedly higher in control area (64%) than intervention areas (Figure 4). The MR clients who mentioned that they experienced complications were asked about the type of complications they faced after MR. It was evident that excessive bleeding and abdominal pain were the major problems the MR clients faced in both intervention and control areas. However, a considerable proportion of MR clients (36%) in control area also faced uterus infection after MR. This is not unexpected because more than one-third of the MR cases in the control area were performed by unskilled providers. It was found that 100% of the respondents in Sylhet started using FP methods after MR, while in Habigonj, 91% respondents started using FP methods after MR. The proportion was 86% in Maulvibazar. It was also evident that some of the respondents did MR more than once. The average number of MR done was lower in intervention area than control area (Tables 9 & 10).

Table 9: Percentage Distribution of MR Clients by type of Complications faced after having the MR by Area.

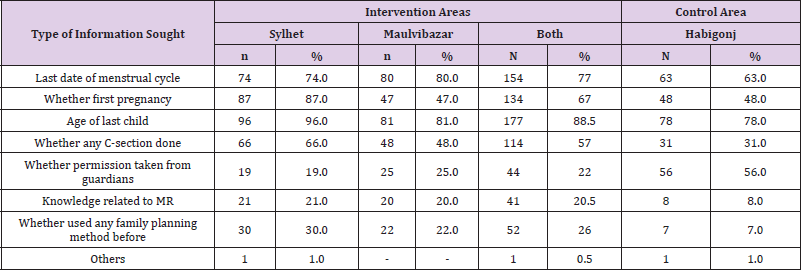

e) Information Sought by Providers before Performing MR: Providing adequate and proper information to women about issues associated with MR is an essential component of safe MR program. The MR clients were asked whether they received any suggestions from provider before the MR. The findings suggest that in intervention areas, very large proportion of clients (90%) received advice before having the MR. In Habigonj, 36% clients reported that they did not receive any suggestion before MR. The findings of the study suggest that health care provider sought information from the client before performing MR. However, the scenario is not the same across the areas. In intervention areas, majority of the respondents informed that the providers asked about last date of menstrual cycle, whether it was first pregnancy, age of the last child, and whether any C-section was done. The proportion of MR client who were asked such questions were lower in control area. Relatively small number of respondents, in both intervention and control areas, stated that providers asked about their knowledge on MR or whether they used any family planning method before (Table 11).

Table 11: Percentage Distribution of MR Clients by type of Information Healthcare Provider Sought from her before MR.

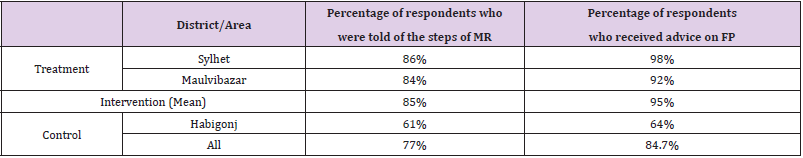

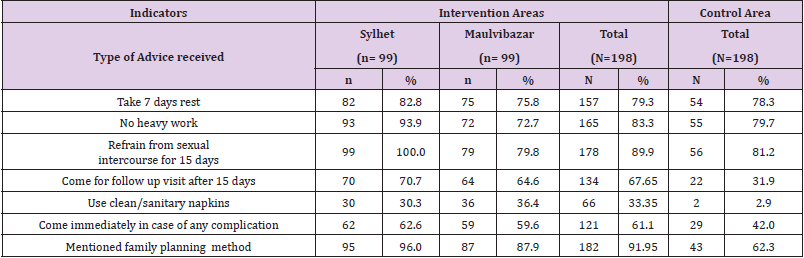

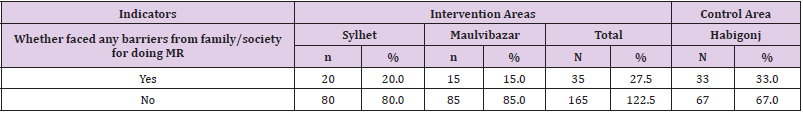

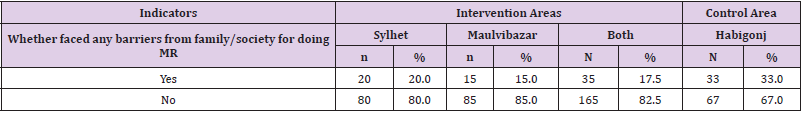

When clients come to the provider for MR, the provider is supposed to inform the MR clients about the various steps involved in the MR procedure. The study finds that a considerably higher proportion of MR clients in intervention areas were told about the steps of MR by the provider as compared to control areas (85% vs 61%). The percentage of respondents who received advice on FP from the MR provider was also noticeably higher in intervention areas than in control area (95% vs 64%) (Table 12). The study also explored the type of advice the MR clients received from the provider after the MR procedure was complete. The findings are presented in (Table 6-13). It shows that the proportion of MR clients who received different advises from the provider were markedly higher in intervention areas than control area. Relatively small proportion of MR clients in control area was told to come for follow up visit after 15 days, use clean sanitary napkin and consult health care provider in case of any complications. It was found that 33% of the respondents in control area faced barriers from their family or community for doing MR.

Table 12: Percentage Distribution of MR Clients who were told of the Steps of MR and Who Received Advice on FP from the Provider: by Area

Table 13: Percentage Distribution of MR Clients by Type of Advice Received from the Provider by Area.

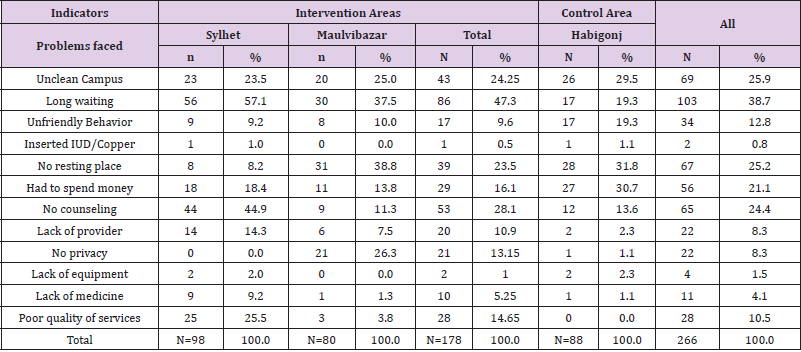

The proportion was considerably lower (about half) in intervention areas (Table 14). MR clients were asked to mention the problems they faced after coming to the facility/provider for doing MR. Long waiting time, no place to rest, no counseling and spending of money were identified as the major problems they faced in the facility (Table 15).

Table 14: Percentage Distribution of MR Clients who faced Problems/Barriers from Family/Society for doing MR: by Area.

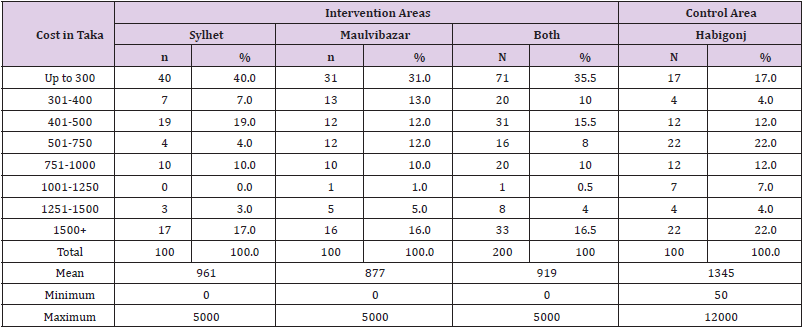

f) Cost Incurred by MR Clients: The cost incurred by MR clients is presented in Table 16. It appears that cost incurred for the MR procedure varies depending on the type of provider. In general, the highest cost was incurred by those had the MR procedure performed by skilled doctor, while the lowest average cost was incurred when MR was performed by village doctor. There was also major difference in average cost by type of provider between the intervention and control area. In general, the mean cost incurred by control area clients was much higher compared to intervention area for each category of provider. The present study suggests that the average cost incurred by an MR client was higher in control area than in intervention areas. It required 877 Taka for MR in Maulvibazar, 961 Taka in Sylhet, and 1345 Taka in Habigonj (Table 16). However, the cost figures may be an underestimate, since costs incurred in connection with transport/travel and food are not included.

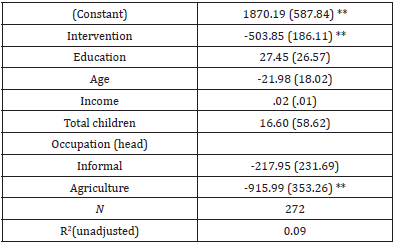

From OLS estimation, for all types of providers together, the costs in the intervention area are significantly lower (99% confidence interval) than in the control area (Table 17). This may be partly explained by the fact that due to capacity building and awareness raising activities FPAB and MSCS in their respective areas, the MR community people in general have better knowledge about the service providers of MR. Similarly, providers in the intervention area have been exposed to the training and advocacy programs of FPAB and MSCS and as a result they are more likely to be aware of women’s right and sympathetic to MR clients. By contrast, women in the control area are caught in a vicious circle when they go for MR. They have to pay more for MR and also receive poor quality of services.

Table 17: OLS Estimation (The Cost of Performing the Procedure).

OLS Estimation; Standard errors presented in parentheses. *p<.05; **p<.01.

g) Post-MR Counseling: This is reflected in the fact that larger proportion of MR clients in the control area faced barriers from their family/society as compared to intervention areas (Table 18).

Table 18: Percentage Distribution of the Respondents Who Faced Problems/Barriers from Family/Society for Doing MR by Area.

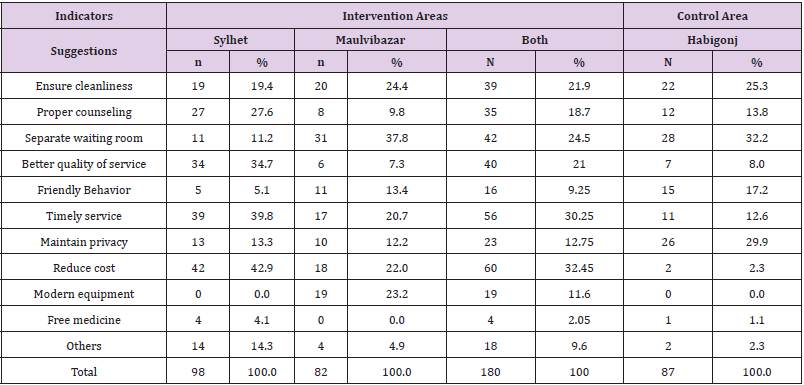

h) Suggestions to Overcome the Barriers: In reply to the question what should be done to improve service provision regarding MR, most of the MR clients suggested that the facility should be clean, there should be separate waiting room, service should be provided timely and privacy should be ensured. The suggestions are listed in Table 19.

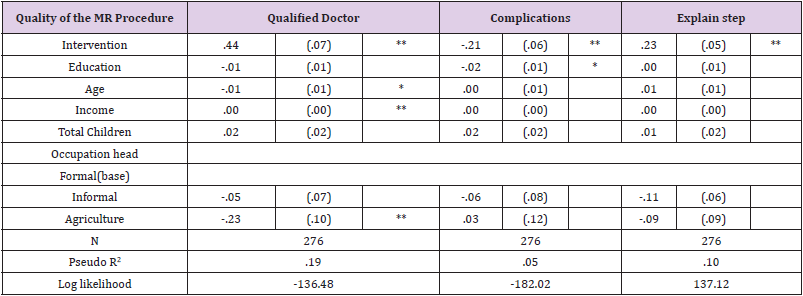

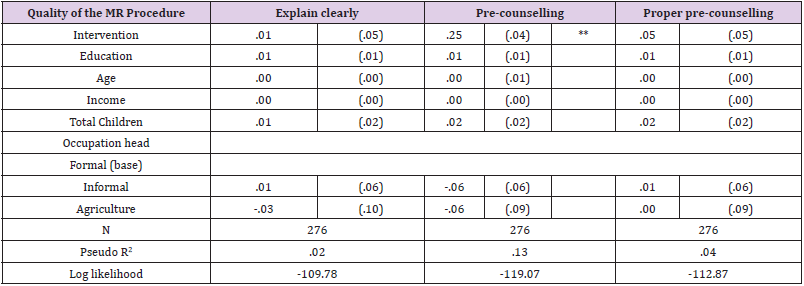

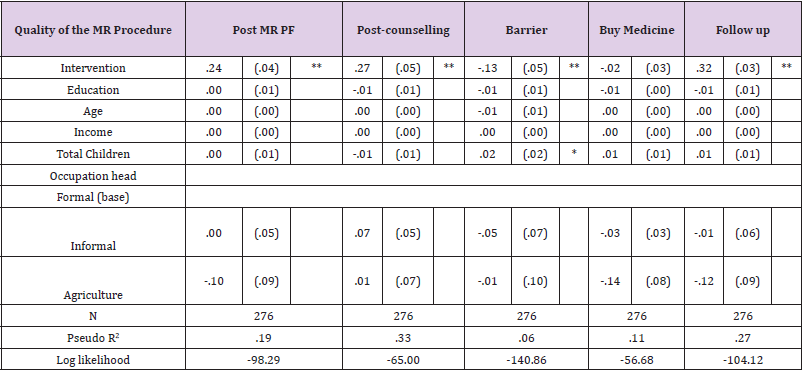

Results from Statistical Analysis (Quality of Care): Some statistical analysis is done considering some indicators stated before (Tables 20-22). MR related complications are an important indicator of quality of MR. The proportion of respondents who faced complications after MR was markedly higher in control area than intervention areas. In the intervention area, a significantly larger proportion of clients had the procedure performed by a skilled doctor than in the control area. Income also significantly contributed to going to a skilled doctor, both in the intervention and in the control area. However, the procedure itself was not sufficiently clearly explained to the clients, neither in the intervention nor in the control area. Complications occurred more frequently in the control area and the difference is statistically significant. Clients in the intervention area also received more frequently suggestions after the MR procedure than clients in the control area, including the advice to take rest and to start using family planning methods. However, the procedure itself was not sufficiently clearly explained to the clients, neither in the intervention nor in the control area.

Table 20: Quality of the MR Procedure (Logistic Regression).

Logit estimation; average marginal effects. Standard errors presented in parentheses. *p<.05; **p<.01

Table 21: Quality of the MR Procedure (Logistic Regression).

Logit estimation; average marginal effects. Standard errors presented in parentheses. *p<.05; **p<.01

Table 22: Quality of the MR Procedure (Logistic Regression).

Logit estimation; average marginal effects. Standard errors presented in parentheses. *p<.05; **p<.01

Results from KIIs

KIIs were conducted in order to complement the findings from the surveys. Key findings are:

a) Awareness creation and mobilization program among the community people on safe timeline for MR, service providers for safe MR and dements of early marriage through focus group discussion, courtyard discussion/meetings, film shows, etc. have contributed to the results obtained. The advocacy programs/seminar organized with government agencies, religious leaders, health professionals and community leaders, in order to recognize, protect and fulfill women’s rights has also contributed to the results obtained

b) Adequate measures were taken for provision of post MR complications, post MR contraceptive services, creation of functional referral mechanism, and referral of high risk cases to higher level public/NGO facilities. All classes of people belonging to different age groups and socio economic categories get the relevant message regarding WHY, WHEN, WHERE, and by WHOM the MR should be performed. This has contributed to increased mass awareness regarding FP and MR related issues.

c) Religious dogma/superstitions among people regarding MR have been reduced. Their knowledge and awareness regarding the need for MR (and avoiding abortion) to terminate unwanted pregnancy has increased significantly. Moreover, their awareness regarding consequences of not using family planning and adverse impact of frequent pregnancies has increased tremendously.

Conclusion

The study is carried out in two intervention (Sylhet and Maulvibazar) and one control (Habiganj) areas. The study sample included 300 respondents- 200 MR clients from intervention and 100 from control areas. The clients were asked different issues (knowledge, attitudes and practices) regarding methods of family planning and MR. The clients in intervention areas were more aware compared to control area. Knowledge about timeline of MR is crucial for safe MR. The present study also assessed the knowledge of MR clients based on their awareness on this timeline of MR. It was found that 74 % of women had correct knowledge about the timeline of safe MR in control area, while the proportion was considerably higher in intervention areas (88%). The intervention has been successful in improving respondents’ knowledge and practice regarding MR. However, it appears that the intervention had a significantly stronger positive effect on the MR clients.

However, it appears that the intervention had a significantly stronger positive effect on the MR clients. MR services utilization is not higher in the intervention area than in the control area, but regarding post-MR counseling there was a difference: it was carried out more frequently in the intervention area and more often it includes family planning services. The proportion of MR clients that had their procedure carried out on time and by a skilled provider was significantly higher in the intervention area than in the control area. Clients in the intervention area faced less complication than clients in the control area, although there is still room for improvement in the intervention area. The quality of pre and postcounseling was also better in intervention area. Both MSCS and FPAB undertook important steps to creating awareness among the policy makers and community level people for considering MR as a women’s rights, thus applying a right based approach. They also confirmed access to safe MR by providing quality MR services. FPAB, for example, delivered educational session on reproductive health and MR.

Another factor was that both MSCS and FPAB invested in capacity development of their staff. Health staff that carried out the MR-procedure was informed on infection prevention and on applying standard guidelines for the procedure in order to improve the quality of the services. Furthermore, an effective referral system was established with GO-NGO-Private service delivery outlets to ensure management of service complications, including post MR complications. The quality of MR services provided by FPAB and MSCS was much better because the client’s history was adequately taken to check for contraindications, good follow-up care was provided, and post-MR complications were managed efficiently and effectively. The findings suggest that the both the service providers has contributed in improving overall knowledge and changing attitude towards safe MR. However, there still remains scope to enhance the knowledge on time line of MR and to improve quality of care.

References

- Ali MS, M Zahir, KM Hasan (1978) "Report on legal aspects of population planning, Bangladesh." Dhaka: The Bangladesl Institute of Law and International Affairs.

- Akhter H, Abortion in Bangladesh, In: Sachdev P (ed.), (1988) International Handbook on Abortion, New York: Greenwood Press 132-133.

- Dixon-Mueller (1988) “Assessing Women’s Economic Contributions to Development”, International Labour Office, 1988, Issue 6 of Background papers for training in population. human resources and development planning 87-92.

- Tietz (1975) An experimental analysis in wage bargaining behavior. Journal of Institutional and Economics 131(1): 1975: 44-91.

- (1979) Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, Memo No. 5-14/MCH-FP/Trg.79, Dhaka, Bangladesh: Population Control and Family Planning Division, 1979.

- (2009) World Bank 2009: “Developing partnerships: Gender, sexuality, and the reformed World Bank”, University of Minnesota Press, 2009.

- (2011) Findings and Implications, Dhaka, Bangladesh: NIPORT, 2011

- (2009) UNDP/GoB "The nexus between urban poverty and local environmental degradation of Rajshahi City". The International Journal of Environmental, Cultural, Economic and Sustainability 5(2): 229-240.

- (2012) WHO 2012: “Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality: an updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000.”, WHO 2012.

- (2011) NIPORT, Bangladesh Maternal Mortality and Health Care Survey 2010, Summary of Key.

- Hossain A, Isaac Maddow-Zimet, Susheela Singh, Lisa Remez (2012) Menstrual regulation, unsafe abortion and maternal health in Bangladesh. In Brief, New York: Guttmacher Institute 3.

- Rochat, Suraiya, Jabeen Michael, J Rosenberg Anthony R Measham Atiqur R Khan, et al. (1981) Maternal and abortion related deaths in Bangladesh 1978-79. International Journal of Gynecology & Obsterics 19(2): 155-164.

- Fauveau V, Blanchet T (1989) Deaths from injuries, and induced abortion among rural Bangladeshi women. Social Science and Medicine 29 (9): 1121-1127.

- (2003) NIPORT 2003: “Bangladesh Maternal Health Services and Maternal Mortality Survey, 2001." Dhaka, Bangladesh: National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT) (2003). Macro, O. R. C., and Johns Hopkins.

- Begum, Syeda Firoza, Haidary Kamal, Sadiqa Tahera Khanam, G M Kamal, et al. (1985) Evaluation of MR services and training pro- grams. Dhaka: BAPSA.

- Germain, Adrienne (1985) Menstrual regulation and induced abortion in Bangladesh. Memo to Oscar Harkavy, the Ford Foundation, New York, USA.

- Akhter H (2001) Currentst at us and access to abortion: the Bangladesh experience, In: Klugman B and Budlender D (eds.), Advocating for Abortion Access: Eleven Country Studies, Johannesburg, South Africa: Women’s Health Project, School of Public Health, University of the Witwatersrand 2001.

- (2009) NIPORT, Mitra and Associates and Macro International, Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey, 2007, Dhaka, Bangladesh and Calverton, MD, USA: NIPORT, Mitra and Associates, Macro International 2009.

- Johnston H (2011) Scaledup and marginalized: are view of Bangladesh’s menstrual regulation programme and its impact. In: Blas E, Sommerfeld J and Karup A (eds.), Social Determinants Approachesto Public Health: From Concept to Practice, Geneva: World Health Organization p. 9-24.

- Hossain, Susheela Singh, Josefina V Cabigon, Haidary Kamal (1997) Estimating the Level of Abortion in the Philippines and Bangladesh. International Family Planning Perspectives 23(3): 100-107.

- Akhter H (2001) Midlevel provider in menstrual regulation, Bangladesh experience, paper presented at the conference Expanding Access: Advancing the Roles of Midlevel Proveders in Menstrual Regulation and Elective Abortion Care, South Africa, Dec 2-6: 2001.

- Chowdhury SN, Moni D (2004) A situation analysis of the menstrual regulation programme in Bangladesh. Reproductive Health Matters 12 (24 Suppl): 95-104.

- Johnston H, Elizabeth Oliveras, Shamima Akhter, Damian Walker (2010) Health system costs of menstrual regulation and care for abortion complications in Bangladesh. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 36(4): 197-204.

- (2011) MR services: performance statistics, in: Health and Rights, Dhaka: Bangladesh, Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR) Consortium 4: (4): 4.

- (2001) NIPORT 2001: Bangladesh Health and Demographic Survey 1999-2000. National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT), 2001.

- Rashid S, Akram O, Standing H (2011) The sexual and reproductive health care market in Bangladesh: where do poor women go? 19(37): 21-31.

- Rashid S (2010) Quality of care and pregnancy terminations for adolescent women in urban slums. in: Abortion in Asia: Local Dilemmas, Global Politics, New York: Bergahn Books, 2010.

- (2007) UNFPA: Annual Report 2006. UNFPA 2007.

Review Article

Review Article