Abstract

Background: Laparoscopy is widely employed to manage primary and post incisional hernias. However, consensus on the best available surgical inlay mesh is still lacking.

Methods: A single-center database was used to compare the perioperative and long-term outcomes of laparoscopic ventral hernia repair completed between 2014 and 2018, using different types of meshes. Of the 79 included patients, 47 (59%) underwent implantation with Dual Mesh™ 17 (22%) with Parietex™ and 15 (19%) with Physio meshTM and the patients were grouped accordingly.

Results: The baseline characteristics of the three groups were similar. Recurrent ventral hernias were more frequent in the Dual Mesh™ group (23.4 vs. 0 vs 0%; P=0.01). Perioperative complications and quality of life scores after surgery were also similar. Postoperative hematomas occurred in 3 (17.6%) patients in the Parietex™ group, in 1 (2.1%) patient in the Dual Mesh™ group and in none of the patients in the Physio mesh™ group (P=0.02). The incidence of recurrence was comparable, although the median follow-up was longer in the Physio mesh™ group (57 months), P=0.001.

Conclusions: Laparoscopy is safe for treating ventral hernias. The choice of one type of mesh over another seems to not be correlated with most perioperative and long-term outcomes.

Keywords: Laparoscopic ventral incisional hernia repair; Meshes

Introduction

The proper approach for ventral hernias, including both post incisional and primary defects, is still under debate. Therefore, no standard operative technique has been accepted by the surgical community due to the high incidence of postoperative morbidity and recurrence [1,2]. Nevertheless, laparoscopic incisional and ventral hernia repair (LIVHR) may represent an alternative to open surgery, avoiding wide recissions and accelerating postoperative return to normal activities. Despite a large number of encouraging papers, reviews, international guidelines [3-9] a meta-analysis [10] and a Cochrane review [11] suggested that LIVHR could be superior to the open approach; other works have reported equivalent/ inferior results or narrow indications [12-15].

Moreover, a major concern is which type of mesh is to be employed. Most leading surgeons agree that an intraperitoneal inert material should be left in contact with the bowel and viscous, although composite meshes (absorbable and non-absorbable layers merged) are an alternative option [16-22]. However, in many public health systems, not all commercial meshes with proper sizes are available, while in private systems, a conflict of interest could play a role in the decision of which is the best product. Therefore, large studies comparing the different types of meshes are still lacking. The aim of the present study is to compare the results of LIVHR performed with different types of meshes in a public hospital.

Materials and Methods

Patients and Setting

A prospective database of LIVHR started in 2014 at Careggi Main Regional and University Hospital, Florence, Italy. All consecutive patients who underwent elective or urgent LIVHRs until December 2019 were retrospectively compared, grouping them according to the type of mesh employed. The indication for surgery was a ventral hernia (primary and post incisional) with a width greater than 2 centimeters in the maximum diameter. Smaller defects were managed under local analgesia with or without a small piece of mesh. No limitation was theoretically posed on the maximum range, but each surgeon was free to decide to use a minimally invasive technique, including for recurrent incisional hernias or urgency. All the involved surgeons had previous robust experience with this operation or were tutored by another surgeon who had experience (i.e., residents).

The preoperative workup included routine clinical examination and abdominal sonography or computed tomography (CT) in selected patients with doubtful bulging or symptoms. Procedurespecific informed consent was obtained from all patients, including for conversion laparotomy. Preoperative variables included baseline characteristics, such as age, sex, body mass index (BMI), comorbidities, past abdominal surgical history, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification, actual employment (retired, active work, sedentary work), and classification of the post incisional hernia according to Chevrel and Rath [23]. The general complications were recorded based on the Clavien-Dindo classification [24]. Patients were followed until discharge or 30 days postoperatively (whichever occurred later) and were then contacted during the outpatient visits or by phone calls for the medium/long-term follow-up (time of the present study). The primary objective was to assess the perioperative outcomes and the medium- to long-term follow-up, including the incidence of recurrence, reoperation, and quality of life (QoL), according to a structured specific questionnaire (Carolinas Comfort Scale, CCS) [25]. Patients who complained of symptoms of recurrence during phone interviews were also invited to the outpatient clinic for confirmation. In doubtful cases, further radiologic (CT scan) examination was also requested.

Surgical Technique

The laparoscopic technique was standardized among operating surgeons and published elsewhere [26], but each surgeon was free to choose his/her preference regarding the pneumoperitoneum, number and size of trocars, instruments for adhesiolysis and management of the hernia sac. The type of mesh was chosen according to the surgeons’ preference or the availability of a proper size. Nevertheless, the mesh was placed intraperitoneally and overlapped the wall defect for at least 4 cm in all directions. Mesh fixation was achieved with a double circular line of helicoidal clips (ProTack™ 5mm; AbsorbaTack™ - Medtronic Italia, Milan, IT), the first at the edge of the mesh and the second as an inner circle, avoiding clipping the sac. Definitive sutures at the cardinal points were not employed routinely. Direct closure of the defect was achieved only in selected cases. The use of drainage suction and compressive dressings (5-7 days until the first outpatient visit) was also employed sporadically.

Grouping

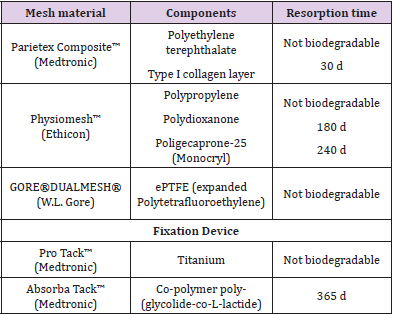

The whole cohort of patients was divided according to the type of mesh employed, excluding those patients who underwent conversion to laparotomy and who had a polypropylene retro muscular mesh according to the Rives-Stoppa technique. Patients who underwent implantation of a type of mesh employed less than 5 times were excluded. Each participating surgeon was free to choose his/her preferred mesh, although the availability of a large spectrum of commercial meshes was not guaranteed, which was kept constant over the study period. Three definitive groups were created: those who received Dual Mesh™ (Gore Newark, DE, USA - ePTFE, expanded-Polytetrafluoroethylene), Parietex™ (Covidien, New Haven, CT, USA - Polyethylene terephthalate and Type I collagen layer), and Physiomesh™ (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ, USA - Polypropylene, Polydioxanone, Polige caprone- 25 Monocryl). The details of the technical characteristics of each type of mesh are summarized in Table 1.

Endpoints

The main endpoints were the determination of whether different types of meshes were related to postoperative complications, medium- to long-term outcomes (including QoL), and incidence of recurrence.

Statistics

Statistical and descriptive analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 25 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). All data were collected prospectively and reviewed retrospectively. Group comparisons based on continuous data were performed using the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test, while discrete variables were matched using the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test when appropriate. The statistical level of significance was defined as a P value <0.05.

Results

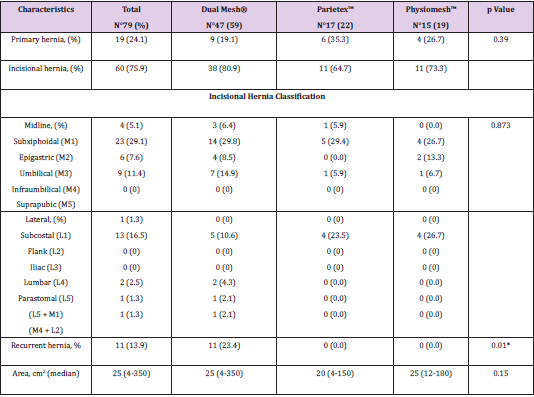

A total of 90 patients underwent an attempted LIVHR between January 2014 and December 2019. Of these, 8 (8.8%) underwent conversion to open surgery. According to the purpose of the study, these 8 patients were excluded from further analysis because the mesh employed was a polypropylene-based prosthesis in the retro muscular position, not to be compared with intraperitoneal prostheses. Three patients (3.3%) completed the planned laparoscopy, although they received 2 different prototypic brandnew meshes that were no longer employed due to the hospital’s policy and were excluded. Therefore, the final cohort was based on 79 patients, with 41 (51.9%) males and 38 (48.1%) females. The retrospective grouping included 47 (59%) patients who underwent implantation of a Dual Mesh™, 17 (22%) of a ParietexTM and 15 (19%) of a Physiomesh™. There were no statistically significant differences in the baseline characteristics of the three groups, including demographics, employment, and comorbidities (Table 2). The distributions of ventral hernias, such as incisional or primary, the area of the defect, and the site subclassification according to Chevrel and Rath [23], were also highly comparable among the 3 groups. Recurrent incisional hernias (at least one failed previous attempt of repair) were more frequent in the Dual Mesh™ group (23.4 vs. 0 vs 0%; P=0.01). The detailed hernia characteristics are provided in Table 3.

Table 2: Demographic characteristics and comorbidities in three mesh groups.

Values are expressed as events (with percentages) or median with ranges.

BMI: Body Mass Index.

ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists classification.

COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Table 3: Hernia characteristics in three mesh groups.

Values are expressed as events (with percentages) or median with ranges. *P<0.05.

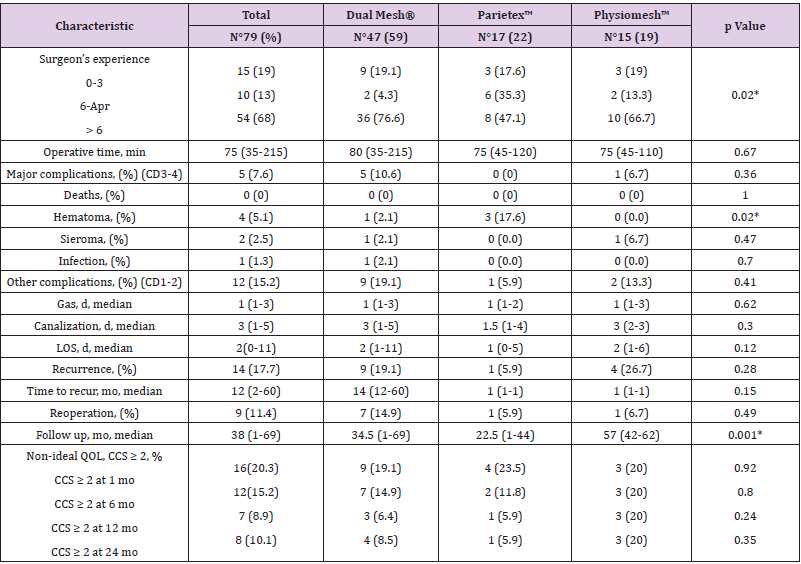

The Dual Mesh™ prosthesis was employed by experienced surgeons (>6 completed LIVHRs) more frequently than the other types of mesh (76.6 vs. 47.1 vs. 66.7%; P=0.02). Mortality was null in the present study. Overall, major morbidity (Clavien-Dindo 3-4) occurred in 6 patients (7.6%), 5 in the Dual Mesh™ group and 1 in the Physiomesh™ group, without statistical significance. Of these, two patients (2.5%) required reintervention, one for intestinal occlusion and another for gastric bleeding (concomitant stromal tumor excision in the first operation). Both were managed laparoscopically without mesh removal. One patient required a colonic immediate suture for an iatrogenic lesion, avoiding cavity contamination. Two patients experienced pneumonia and were treated with oral antibiotics (one after 3 days in the High Dependency Unit, a patient in the Physiomesh™ group). One patient experienced anemization in the early postoperative period and was transfused. All these patients were discharged without further complications.

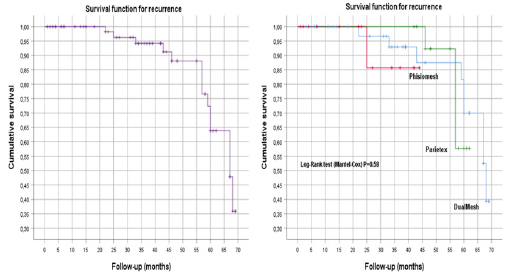

Hospital stay, readmissions, and QoL, calculated according to the CCS, were similar within groups. Postoperative hematomas occurred in 3 (17.6%) patients in the Parietex™ group, in 1 (2.1%) patient in the Dual Mesh™ group and in none of patients in the Physiomesh™ group (P=0.02). Other minor complications (Clavien- Dindo 1-2) included 2 patients with prolonged abdominal pain (2.5%), 4 (5%) with transient fever of uncertain origin, 1 with transient arrhythmia, 1 with biliary vomiting and 3 with multiple comorbidities who required 24 h of intensive care observation. The details of perioperative and medium- to long-term followup are reported in Table 4. The incidence of recurrence was comparable, such as the time between the operation and the onset of new bulging, although the median follow-up was longer in the Physiomesh™ group (57 months) than in the DualMesh™ group (34.5 months) and ParietexTM group (22.5 months), P=0.001. Due to the different durations of follow-up, a Kaplan-Meier survival curve was also plotted to report the cumulative incidence of recurrence (5.8% at 36 months) (Figure 1A). After proper calculation with the log-rank test, the incidence of recurrence, with the three different types of meshes, was not significantly different (P=0.58) (Figure 1B).

Figure 1: Survival function for hernia recurrence (A) and hernia recurrence for different types of meshes (B).

Table 4: Surgical outcomes after laparoscopic ventral hernia repair.

Values are expressed as events (with percentages) or median with ranges. *P<0.05.

CD: Clavien-Dindo

LOS: Length of stay

QOL: Quality of life

CCS: Carolina Comfort Scale

Discussion

To date, this is one of the few studies comparing different types of commercially available meshes for LIVHR. The main results are represented by the negligible differences in both the postoperative outcomes and the incidence of recurrence. Laparoscopic incisional and ventral hernia repair (LIVHR) is a good alternative to open surgery, although no definitive conclusions regarding this technique have been published, and many papers, meta-analyses and reviews have reported conflicting results regarding indications, technical details and types of meshes to be employed [3-11,15]. Many types of meshes have been employed, although no ‘ideal’ mesh is commercially available, leading to caution when comparing the results. The present study included a very homogeneous population among the three different types of meshes employed, excluding selection biases at this level. The only preoperative difference was represented by the higher incidence of recurrent incisional hernias in patients treated with Dual Mesh™. A possible explanation could be found in the preference of the more experienced operating surgeons, which represents a limitation of the study. However, no differences were found in the groups regarding the size of the defects or challenging locations.

Interestingly, major complications occurred mostly in patients who received the Dual Mesh™ prosthesis, although no statistically significant difference was detected. To date, the largest multicenter casistic published on LIVHR was that of Sanchez and coworkers [26], in which more than 2000 patients were treated using an ePTFE mesh with outcomes comparable to those achieved in the present study. Although bowel adhesion and subsequent obstruction should occur with uncoated meshes, we observed only one postoperative occlusion directly related to mesh adhesions [27]. All the other complications were related to adhesiolysis or to medical diseases, and no further complications were observed, such as mesh infection, in complicated patients (bleeding and bowel lesion) in the present series. In contrast with previous experience [17-23], our study failed to support the theoretical advantages of composite meshes (non-absorbable materials coated by absorbable or inert layers) over ePTFE (inert non-absorbable materials).

Postoperative seroma formation is a frequent event (up to 10%), while true hematomas are also a reported occurrence [14]. Seroma/hematoma formation was a rare event in our casistic, without significant differences between groups, as reported by other authors for composite meshes [15]. A possible explanation could be found in the difference in the reporting of “seroma”: according to some authors, only prolonged seromas (more than 2-4 weeks) should be considered a true complication [6,28]. To date, only one randomized controlled trial comparing mesh types (titaniumcoated lightweight mesh vs. standard composite mesh) has been published. The authors reported only less pain in the titaniumcoated mesh group, without any other significant differences [29]. In addition to mild perioperative impairments, the incidence of recurrence should be considered a major endpoint of hernia repair. Our study revealed no statistically significant difference between the different types of meshes in terms of recurrence, even when performing a Kaplan-Meier survival curve to compare different lengths of follow-up.

Limitations

The main bias of the present study is that it is neither prospective nor randomized. However, the choice of one mesh rather than another was mainly related to each participating surgeon (nine staff surgeons supervising residents or colleagues), although the preferred mesh (or the proper size) was not always available, leading to some “single-day” randomization. For example, the Phisiomesh™ prosthesis was withdrawn from the market during the study period, without correlations to complications occurring at our hospital. Moreover, some conflicting results could be related to the different types of tax (i.e., absorbable or titanium) employed to secure the mesh, rather than the mesh itself [30,31]. This aspect was not taken into consideration in the present study, although most of the operations were completed by titanium tacks or a mix of titanium and absorbable tacks. Again, the same differences in the surgical technique, such as the occasional closure of the defect or the adjunct of trans fascial sutures, could also have played a role in determining the incidence of recurrence and outcome [32-34].

Conclusions

LIVHR is a safe and feasible technique for managing both primary and postincisional hernias. Despite the theoretical advantages of composite meshes, very few significant differences could be detected when compared to ePTFE in the present study. Large multicenter randomized controlled studies without market or personal influences should be designed to choose the best product.

References

- Den Hartog D, Dur AH, Tuine breijer WE, Kreis RW (2008) Open surgical procedures for incisional hernias. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 16: CD006438.

- Liang MK, Holihan JL, Itani K, Alawadi ZM, Gonzalez JR, et al. (2017) Ventral hernia management: expert consensus guided by systematic review, Ann. Surg 265(1): 80-89.

- Eker HH, Hansson BM, Buunen M, Janssen IM, Pierik RE, et al. (2013) Laparoscopic vs. open incisional hernia repair: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg 148(3): 259-263.

- Bittner R, Bingener-Casey J, Dietz U, Fabian M, Ferzli GS, et al. (2014) Guidelines for laparoscopic treatment of ventral and incisional abdominal wall hernias (International Endohernia Society [IEHS]) Part 2. Surg Endosc 28: 353-379.

- Bittner R, Bingener-Casey J, Dietz U, Fabian M, Ferzli G, et al. (2014) Guidelines for laparoscopic treatment of ventral and incisional abdominal wall hernias International Endohernia Society [IEHS] - Part III, Surg. Endosc 28: 380-404.

- Silecchia G, Campanile FC, Sanchez L, Ceccarelli G, Antinori A, et al. (2015) Laparoscopic ventral/incisional hernia repair: updated Consensus Development Conference based guidelines, Surg. Endosc 29(9): 2463-2484.

- Earle D, Roth JS, Saber A, Haggerty S, Bradley JF, et al. (2016) SAGES Guidelines Committee. SAGES guidelines for laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. Surg Endosc 30: 3163-3183.

- Birindelli A, Sartelli M, Di Saverio S, Coccolini F, Ansaloni L, et al. (2017) update of the WSES guidelines for emergency repair of complicated abdominal wall hernias. World J Emerg Surg 7(12): 37.

- Heniford BT (2016) SAGES guidelines for laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. Surg Endosc 30(8): 3161-3162.

- Arita NA, Nguyen MT, Nguyen DH, Berger RL, Lew DF, et al. (2015) Laparoscopic repair reduces incidence of surgical site infections for all ventral hernias, Surg. Endosc 29(7): 1769-1780.

- Sauerland S, Walgenbach M, Habermalz B, Seiler CM, Miserez M (2011) Laparoscopic versus open surgical techniques for ventral or incisional hernia repair, Cochrane Database Syst. Rev 16: CD007781.

- Al Chalabi H, Larkin J, Mehigan B, McCormick P (2015) A systematic review of laparoscopic versus open abdominal incisional hernia repair, with meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, Int. J. Surg 20: 65-74.

- Awaiz A, Rahman F, Hossain MB, Yunus RM, Khan S, et al. (2015) Meta-analysis and systematic review of laparoscopic versus open mesh repair for elective incisional hernia, Hernia 19: 449-463.

- Meyer R, Häge A, Zimmermann M, Bruch HP, Keck T, et al. (2015) Is laparoscopic treatment of incisional and recurrent hernias associated with an increased risk for complications? Int. J. Surg 19: 121-127.

- Schlosser KA, Arnold MR, Otero J, Prasad T, Lincourt A, et al. (2019) Deciding on Optimal Approach for Ventral Hernia Repair: Laparoscopic or Open. J Am Coll Surg 228(1): 54-65.

- Moreno-Egea A, Liron R, Girela E Aguayo JL (2001) Laparoscopic repair of ventral and incisional hernias using a new composite mesh (Parietex): initial experience. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 11(2): 103-106.

- Balique JG, Benchetrit S, Bouillot JL, Flament JB, Gouillat C, et al. (2005) Intraperitoneal treatment of incisional and umbilical hernias using an innovative composite mesh: four-year results of a prospective multicenter clinical trial. Hernia 9: 68-74.

- Kayaoglu HA, Ozkan N, Hazinedaroglu SM, Ersoy OF, Erkek AB, et al. (2005) Comparison of adhesive properties of five different prosthetic materials used in hernioplasty. J Invest Surg 18(2): 89-95.

- McGinty JJ, Hogle NJ, McCarthy H, Fowler DL (2005) A comparative study of adhesion formation and abdominal wall ingrowth after laparoscopic ventral hernia repair in a porcine model using multiple types of mesh. Surg Endosc 19: 786-790.

- Chelala E, Debardemaeker Y, Elias B, Charara F, Dessily M, et al. (2010) Eighty-five redo surgeries after 733 laparoscopic treatments for ventral and incisional hernia: adhesion and recurrence analysis. Hernia 14: 123-129.

- Deeken CR, Faucher KM, Matthews BD (2012) A review of the composition, characteristics, and effectiveness of barrier mesh prostheses utilized for laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. Surg Endosc 26(2): 566-575.

- Tandon A, Shahzad K, Pathak S, Oommen CM, Nunes QM, et al. (2016) Parietex™ Composite mesh versus DynaMesh®-IPOM for laparoscopic incisional and ventral hernia repair: a retrospective cohort study. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 98(8): 568-573.

- Chevrel JP, Rath AM (2000) Classification of incisional hernias of the abdominal wall, Hernia 4: 7-11.

- Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, et al. (2009) The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg 250(2): 187-196.

- Heniford BT, Lincourt AE, Walters AL, Colavita PD, Belyansky I, et al. (2018) Carolinas Comfort Scale as a Measure of Hernia Repair Quality of Life: A Reappraisal Utilizing 3788 International Patients. Ann Surg 267(1): 171-176.

- Sánchez LJ, Piccoli M, Ferrari CG, Cocozza E, Cesari M, et al. (2018) Laparoscopic ventral hernia repair: Results of a two thousand patients prospective multicentric database. Int J Surg 51: 31-38.

- Schreinemacher MH, van Barneveld KW, Dikmans RE Gijbels MJ, Greve JW, et al. (2013) Coated meshes for hernia repair provide comparable intraperitoneal adhesion prevention. Surg Endosc 27(11): 202-209.

- Moreno-Egea A, Carrillo-Alcaraz A, Soria-Aledo V (2013) Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic hernia repair comparing titanium-coated lightweight mesh and medium-weight composite mesh. Surg Endosc 27(1): 231-239.

- Morales-Conde S (2013) A new classification for seroma after laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. Hernia 16(2012): 261-267.

- Pawlak M, Hilgers RD, Bury K, Lehmann A, Owczuk R, et al. (2016) Comparison of two different concepts of mesh and fixation technique in laparoscopic ventral hernia repair: a randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc 30(3): 1188-1197.

- Christoffersen MW, Westen M, Rosenberg J, Helgstrand F, Bisgaard T (2020) Closure of the fascial defect during laparoscopic umbilical hernia repair: a randomized clinical trial. Br J Surg 107(3): 200-208.

- Bernardi K, Olavarria OA, Holihan JL, Kao LS, Ko TC, et al. (2020) Primary Fascial Closure During Laparoscopic Ventral Hernia Repair Improves Patient Quality of Life: A Multicenter, Blinded Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Surg 271(3): 434-439.

- Wassenaar E, Schoenmaeckers E, Raymakers J van der Palen J, Rakic S (2010) Mesh-fixation method and pain and quality of life after laparoscopic ventral or incisional hernia repair: a randomized trial of three fixation techniques. Surg Endosc 24(6): 1296-1302.

- Chelala E, Baraké H, Estievenart J, Dessily M, Charara F, et al. (2016) Long-term outcomes of 1326 laparoscopic incisional and ventral hernia repair with the routine suturing concept: a single institution experience, Hernia 20: 101-10.

Research Article

Research Article