Abstract

Emergency departments (ED) are evidently prone to medical error. The World Health Organization (WHO) specifically proposed improving interprofessional collaboration as an important way to reduce it, supporting the implementation of interprofessional education in medical education. First step is to establish a shared understanding of what, how and why of interprofessional education and interprofessional practice. Development coronavirus disease 2019 has had serious implications for health institutions and raises particular questions for medical schools and represent an enduring transformation in medical education.

IPE initiatives have been supported by Health Canada since 2002, when the Romanow Report stated that:

“If health care providers are expected to work together and share expertise in a team environment, it makes sense that their education and training should prepare them for this type of working arrangement.” [1]

Introduction

Interprofessional Education (IPE) refers to “occasions when two or more professionals learn with, from and about each other to improve collaboration and the quality of care” and “improve health outcomes” [2,3]. This contrasts with multi-professional education where health professionals learn alongside one another in a parallel manner, and with Interprofessional Practice (IPP) or “Collaborative Practice” “occurs when multiple health workers from different professional backgrounds provide comprehensive services by working with patients, their families, carers and communities to deliver the highest quality of care across settings” [3].

Interprofessional Team-Based Care is “Care delivered by intentionally created, usually relatively small work groups in health care who are recognized by others as well as by themselves as having a collective identity and shared responsibility for a patient or group of patients (e.g., rapid response team, palliative care team, primary care team, and operating room team).” Is different from Interprofessional Teamwork that is “The levels of cooperation, coordination and collaboration characterizing the relationships between professions in delivering patient-centered care” [4].

Current evidence shows that IPE is an strong tool to develop cooperation and efficiency among health workers of different professions, improve professional practice and health care and outcomes, improve interdisciplinary collaboration and teamwork, reduces the barriers and preconceptions prevailing among various healthcare groups, promotes professional competencies, enhance future health workers’ clinical and medical knowledge and clinical skills [5,6].

The WHO has supported IPE because of its usefulness, and its intention is to program and operate it in all countries. A current disadvantage is limited evidence from developing countries. The evidence comes from developed countries about its efficiency, challenges, and barriers, which may limit implementation IPE in developing countries, and its guidelines for transformative medical education, were based on evidence derived from developed countries, and WHO invites nations to promote IPE and include it in their curriculum [7]. This “is a corner stone for its sustainability and cost effectiveness which can help IPE adoption even in resourceconstrained countries” [3,8].

A range of mechanisms shape effective interprofessional education and collaborative practice. Some of them are: Supportive management practices; The resolve to change the culture and attitudes of health workers; Appropriate legislation that eliminates barriers to collaborative practice; A willingness to update, renew and revise existing curricula; And Identifying and supporting champions [3]. Interprofessional collaboration is very important for patient safety and quality of care, and there is currently enough evidence to indicate that IPE prepares students to achieve it. All this helps to improve and strengthen health and services systems, and thus health outcomes [9]. In both acute and primary care settings, patients report higher levels of satisfaction, better acceptance of care and improved health outcomes following treatment by a collaborative team [10].

“Learning Together to Work Together for Better Health” [11]

When students are expected to show interprofessional collaboration (IPC) in real or simulated health care situations, their attitudes should be strong enough to guide their behavior. For IPE, this implies that when IPC is the learning goal for our students, we need to ascertain the strength of their attitudes rather than (just) observing their behavior [12].

Many university hospitals have implemented IPE interventions in clinical settings in the form of student-led inpatient wards. In this IPE model, students of different healthcare professions treat patients together, with the intention of training the team with the support and guidance of supervisors. Evaluations have shown a high degree of goal achievement and this model of IPE is now broadly accepted in many health science universities and colleges (eg. Sweden) as an appropriate and effective approach to teaching collaborative and communicative skill [13,14].

Dr Wilbur asserts that emergency medicine is the specialty best prepared to lead reforms in the current fragmented system of education and health care delivery, because its appreciate the direct effects of collaborative practice; has keen perspective; creates solutions when resources are limited; innovate when others are tradition-dependent; appreciates the continuum of education; understands, use, and teach evidence-based methodologies. Conflicts between health professionals from different disciplines usually has the root in communication, lack of understanding of separate perspectives, lack of respect of the other’s opinion, etc.… and that it is a function of training, and it must change [15].

Successful Implementation of IPE Requires Leadership at All Level (Schmitt MH, 2013)

Administrative and academic leaders should be supportive in providing expertise and resources for effective delivery of IPE [16], and clinical leadership has important role in connecting the interprofessional education to interprofessional practice. This support carries a strong promise of enhancing IPE effectiveness with consequent improved patient care and safety.

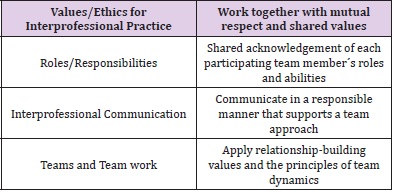

Reforms could be done through the “Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice” released by Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC). They used bestpractices methodology to establish four IPE competency domains (Table 1).

There are significant improvements after embedding IPE module in various medical fields as enhanced acquisition of knowledge, skills, and attitudes of learners about collaborative teamwork [5]. IPE improved knowledge, skills and behavior of interprofessional collaborative competences and patient satisfaction, and IPE acts as a bridging medium between health professional education and the health care system [17]. IPE curriculum challenges (such content, curriculum integration, time and schedule, rigidity), leadership weakness, resources (such financial challenges, physical infrastructure and distance), attitudes and stereotypes, student´s characteristics, IPE concept, teaching barriers, enthusiasm, profession jargons and accreditation are some barriers to IPE implementation in developed countries [7]. Evidence is scarce on IPE in developing countries, but all these barriers are also potentially important for developing countries [18,19].

What About After COVID-19 Pandemic?

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak has rapidly transitioned into a worldwide pandemic and has the potential to affect students throughout the educational process. This development has had serious implications for health institutions and raises particular questions for medical schools, also may forever change how future healthcare professionals are educated and requires intense and prompt attention from educators [20].

Despite medical education and professional training across the world have experienced a major disruptive change as a consequence of this pandemic, several resourceful initiatives have been implemented, leading to progress in medical education. The provision of educational content and training online has increased to facilitate student learning and training [21], as well as faculty development in the use of technology. The current response to the pandemic has been the increased awareness and adoption of currently available technologies in health education [22]: online courses and discussions forums, online problem-based learning, streamed online lectures, interactive webinars, real-time online chat, interactive patient sessions, clinical didactic sessions online, telehealth environment, online training in interpersonal and inter professional communication and clinical skills; real time mobile video tools, apps, podcasts, computer simulations, online platforms (websites, blogs) [23].

These methods proved incredibly popular, and also students have been involved and committed as part of the workforce for the future [24,25], but this current technology will be inefficient and inappropriate to meet the high demand.

The future of health education is uncertain and his change and extent of transformation after this pandemic resolves it is inevitable. Several potential scenarios are discussed about the change and future of teaching and learning. The change will be transformative with conversion factors that will have a major impact on the future way that educators and their institutions will provide medical education. These factors include the number and availability of educators, individual and collective acceptance and commitment to the use of technology, economic constraints and the need to rapidly expand the clinical workforce across health education [26].

To highlight how emergent technology has the potential to transform future provision of higher education, was produced the 2020 EDUCASE Horizon report Teaching and Learning Edition [27]. This report profiles key trends and emerging technologies and practices shaping the future of teaching and learning and envisions a number of scenarios and implications for that future. It is based on the perspectives and expertise of a global panel of leaders from across the higher education landscape. Horizon Report identifies main emerging technologies and practices being shaped by influential social, technological, economic, higher education, and political trends, and also highlights the essential need to strengthen adaptive learning, artificial intelligence, learning engineering and the increasing trend for Open Educational Resources (OER) that will be available without restriction [28-30].

Definitely the changes after the pandemic can have a positive impact on both educators and students across the world [31,32]. Students and educators must help document and analyze the effects of current changes to learn and apply new principles and practices to the future. This is not only a time to contribute to the advancement of medical education in the setting of active curricular innovation and transformation, but it may be a seminal moment for many disciplines in medicine [33,34].

References

- Romanow (2002) Building on values: the future of health care in Ontario. Ottawa: Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada.

- Zwarenstein MAJ (1999) A systematic review of interprofessional education. J Interprof Care 13(4): 417-424.

- (2010) World Health Organization (WHO) (2010) Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice. Switzerland.

- (2016) Interprofessional Education Collaborative (2016) Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: 2016 Update. Washington, DC.

- Yousuf SB (2018) The effectiveness of interprofessional education in healthcare: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Kaohsiung J Med Sci 34(3): 160-165.

- Barr H, Ross F (2006) Mainstreaming interprofessional education in the United Kingdom: a position paper. J Interprof Care 20(2): 96-104.

- Sunguya BF, Hinthong W, Jimba M, Yasuoka J (2014) Interprofessional Education for Whom? - Challenges and Lessons Learned from Its Implementation in Developed Countries and Their Application to Developing Countries: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 9(5): e9672.

- Brashers V, Peterson C, T Dorothy, Schmitt M (2012) The University of Virginia interprofessional education initiative: an approach to integrating competencies into medical and nursing education. J Interprof Care 26(1): 73-75.

- Malone D, Marriott SVL, Newton Howes G, Simmonds S, Tyrer P (2007) Community mental health teams for people with severe mental health problems. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

- Mickan S (2005) Evaluating the effectiveness of health care teams. Australian Health Review, 29(2): 211-217.

- Health D (2001) Working together, learning together: a framework for lifelong learning for the NHS. London.

- Cora LF, Ket J, Croiset G, Kusurkar RA (2017) Perceptions of residents, medical and nursing students about Interprofessional education: a systematic review of the quantitative and qualitative literature. BMC Medical Education 17(1): 77.

- Hallin KK, Kiessling A, Waldner A, Henriksson P (2009) Active interprofessional education in a patient-based setting increases perceived collaborative and professional competence. Medical Teacher 31(2): 151-157.

- Ponzer S, Hylin U, Kusoffsky A, Lauffs M, Lonka K, et al. (2004) Interprofessional training in the context of clinical practice: Goals and students’ perceptions on clinical education wards. Medical Education 38(7): 727-736.

- Wilbur L (2014) Interprofessional Education and Collaboration: A Call to Action for Emergency Medicine. Resident Portafolio Society for Academic Emergency Medicine 21(7): 833-834.

- Blue AV, Maralynne M, Thomas S, John R, Raymond G (2010) Changing the future of health professions: embedding inter- professional education within an academic health center. Acad Med 85(8): 1290-1295.

- Riskiyanaa R, Claramita M, Rahayu GR (2018) Objectively measured interprofessional education outcome and factors that enhance program effectiveness: A systematic review. Nurse Education Today 66: 73-78.

- Hosny S, Shehata HM, El-Wazir Y, Gilbert J (2013) Integrating interprofessional education in community-based learning activities: case study. Med Teach 35(1): S68-73.

- Wessels Q, Rennie T (2013) Reflecting on interprofessional education in the design of space and place: lessons from Namibia. J Interprof Care 27(2): 69-71.

- (2014) Institute for Healthcare Improvement (2014) Improving Health and Health Care Worldwide.

- Schmitt MH, John HV Gilbert, Barbara F Brandt, Ronald S Weinstein (2013) The coming of age for interprofessional education and practice. Am J Med 126(4): 284-288.

- Guraya SY, Barr H (2017) The effectiveness of interprofessional education in healthcare: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 34: 160-165.

- Ericson A, Lofgren S, Bolinder G, Reeves S, Kitto SC, et al. (2017) Interprofessional education in a student-led emergency department: A realist evaluation. Journal of Interprofessional Care 31(2): 199-206.

- Hammick M, Freeth D, Koppel I, Reeves S, Barr H (2007) A best evidence systematic review of interprofessional education: BEME guide no. 9. Med Teach 29(8): 735-751.

- Reeves S, Goldman J, Gilbert J, Tepper J, Silver I, et al. (2011) A scoping review to improve conceptual clarity of interprofessional interventions. J Interprof Care 25(3):167-174.

- Nadolski GJ, Mary A Bell, Barbara B Brewer, Richard M Frankel, Herbert E Cushing (2006) Evaluating the quality of interaction between medical students and nurses in a large teaching hospital. BMC Med Educ 6(1): 23.

- Pollard KC, Miers EM (2008) From students to professionals: results of a longitudinal study of attitudes to pre-qualifying collaborative learning and working in health and social care in the United Kingdom. J Interprof Care 22(4): 399-416.

- Juge VM, Cullati S, Blondon KS, Hudelson P, Maitre F, et al. (2013) Interprofessional collaboration on an internal medicine ward: role perceptions and expectations among nurses and residents. PLoS One 8(2).

- McFadyen AK, Webster SV, Maclaren WM, O'neill MA (2010) Interprofessional attitudes and perceptions: results from a longitudinal controlled trial of pre-registration health and social care students in Scotland. J Interprof Care 24(5): 549-564.

- Hylin U, Nyholm H, Mattiasson AC, Ponzer S (2007) Interprofessional training in clinical practice on a training ward for healthcare students: a two-year follow-up. J Interprof Care 21(3): 277-288.

- Hutchings M, Scammell J, Quinney A (2013) Praxis and reflexivity for interprofessional education: towards an inclusive theoretical framework for learning. J Interprof Care 27(5): 358-366.

- van Soeren M, Cop DS, Macmillan K, Baker L, Lee EE, et al. (2011) Simulated interprofessional education: an analysis of teaching and learning processes. J Interprof Care 25(6): 434-440.

- Hansson A, Foldevi M, Mattsson B (2010) Medical students' attitudes toward collaboration between doctors and nurses: a comparison between two Swedish universities. J Interprof Care 24(3): 242-250.

- Baggs JG, Schmitt MH (1997) Nurses' and resident physicians' perceptions of the process of collaboration in an MICU. Res Nurs Health 20(1): 71-80.

Review Article

Review Article