Abstract

Studies in Mali found insufficient coverage of interventions focused on malaria prevention during pregnancy. We performed secondary data analysis from the 2015 Malaria Indicator Survey of Mali (MIS) to assess the effectiveness of IPTp-SP during pregnancy. ANC attendance was high, with 94.6% of pregnancy women attending at least one ANC visit and 43.4% had their first visit in the second trimester. IPTp-SP uptake (at least one dose of SP) was 68.7% among those received SP, 63.1% had completed at least 2 SP-doses. Women aged ≥35 years and from 20 to 34 years had higher IPTp uptake (71.1% and 69.6%, respectively). The coverage rate of ITPp increased with illiteracy from 65.2% of primary level to 78.5% of high level. In rural area IPTp-SP uptake (69.1%) and ANC visit (73.5%) were more practice. In multivariate analysis, marital status, household wealth quintile, educational level and rural residency were significantly associated with vIPTp2+ uptake. From 2012 to 2015 significant progress has been made in IPTp coverage, but coverage is still far below WHO targets despite a moderately high level of ANC attendance. Keywords: IPTp-SP, Coverage, Mali

Title: Coverage of interventions against malaria during antenatal consultations in Mali In Mali, studies have reported insufficient coverage of interventions aimed at preventing malaria in pregnancy. We performed a secondary analysis of data from the 2015 Mali Malaria Indicator Survey to determine factors associated with the effectiveness of intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxinepyrimethamine during pregnancy. Pregnant women who made at least one ANC visit were 94.6%, of which 43.4% made their first visit in the second trimester. The frequency of women who received at least one dose of SP was 68.7%, of which 63.1% received at least 2 doses of SP. Women aged 35 and over, and those aged 20 to 34 received more IPTp-SP dose with 71.1% and 69.6% respectively. The coverage rate for ITPg-SP increased with literacy, from 65.2% at primary level to 78.5% at higher level. In rural areas, taking IPTp-SP (69.1%) and visiting ANC (73.5%) were more common. On multivariate analysis, marital status, household wealth quintile, level of education and rural residence were significantly associated with the intake of two or more doses of IPTp-SP. From 2012 to 2015, significant progress was made in IPTp coverage, but coverage is still well below WHO targets despite a moderately high level of ANC attendance.

Keywords: TPIg-SP, Coverage, Mali

Introduction

Malaria during pregnancy remains a major public health problem in endemic areas of the African region where approximately 25-30 million of pregnant women are at risk of Plasmodium falciparum infection and its adverse effects during pregnancy [1,2]. In order to reduce the burden of malaria during pregnancy, the World Health Organization (WHO) currently recommends Intermittent Prevetive Treatment in pregnancy using sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (IPTp- SP) and Insecticide Treated mosquito Net (ITN) use in areas of stable (high) transmission of P. falciparum [1]. Antenatal care (ANC) from trained health care professionals is essential in order to anticipate adverse issues and complications to ensure a safe birth. ANC visits provide a forum for delivery of key maternal health interventions including those designed to prevent malaria. Over the past five years, coverage of key interventions against malaria during pregnancy has improved significantly in some African countries but is still low in majority of sub-Saharan Africa countries [3].

Findings from national household surveys showed that, on average, 17% of pregnant women slept under ITNs and 25% of those receiving at least one dose of IPTp-SP [4]. The main barriers to understanding the reasons for low coverage of interventions include health system failures, lack of effective monitoring in data collection, inadequate use of data for program management at local level. Studies examining factors affecting the delivery, access and use of interventions to prevent malaria during pregnancy in sub-Saharan Africa have identified education, knowledge and perception of malaria, socio-economic status, number and timing of ANCs, number of pregnancies, health system problems as factors influencing coverage of interventions as well as access to antenatal care services [5-8]. In Mali, malaria affects more than 600,000 births per year, of which 19.3%, 13.5%, and 54.0%, respectively, result in placental malaria, low birth weight (LB) and maternal anemia.

Review of DHS data in Africa on malaria interventions coverage during pregnancy among pregnant women suggests that there are inadequacies in antenatal care services informing about missed opportunities for intervention delivery of service against malaria in pregnancy. Literature review shows that often the reasons for low coverage are in fact simple misunderstandings that are not difficult to resolve once they are identified, but they vary from country to country, from district to district health [9]. The aim of this study was to assess malaria interventions coverage to control malaria in pregnancy during household survey in Mali in 2015.

Material and Method

The 2015 Mali Malaria Indicator Survey (MMIS) data were used for this analysis. The MIS is a cross-sectional survey with a two-stage cluster design, intended to collect nationally and regionally representative information on coverage of key malaria control interventions and to collect biomarker data (anemia and malaria parasitemia) in children under five years. Data collection was performed from 19 September to 20 November 2015. In all households selected for this survey, all women between 15 and 45 of age were interviewed. Information on ANC attendance, SP uptake and ITN ownership and use were collected. IPTp indicators report on the proportion of women with a live birth in the previous two years who received the intervention during her most recent pregnancy. Overall, 7,623 women aged 15-49 years were interviewed successfully on their last pregnancy experiences resulting in live births.

The protocol had the approval of the National Ethics Committee for Health Sciences of Mali and the CDC Ethics Committee, Atlanta. Data entry was done with CSPro software and analyzed on Stata version 14. Bivariate analysis allowed us to determine the distribution of parameters within the study popluation and the relationship between the outcome variable (IPTp2+) with some predictive factors, and multivariate logistic regression was used to determine the factors associated with SP delivery. Age and parity were categorized as follows: age (<20, 20–34, ≥35) years; parity: primiparae, secundiparae and multiparae (≥3 pregnancies). Complete ANC attendance was considered to be at least four ANC visits during pregnancy (yes/no). The outcome variable is binary and is defined as at least complete two or more doses of SP administered during the pregnancy (IPTp2+) (yes/no).

Results

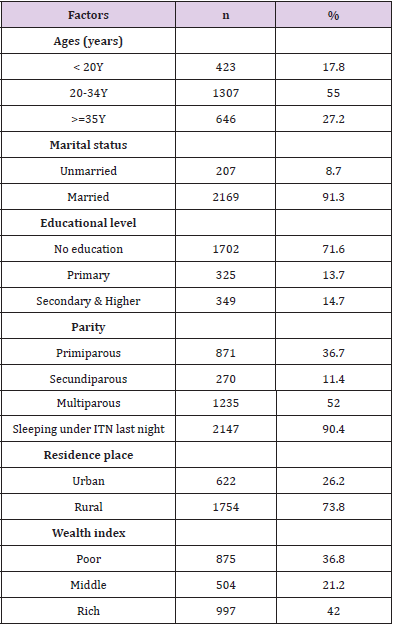

The moajority of study population was aged from 20 to 34 years (55%) with a median age of 27 (15-49) years. The majority of women were married (91.3%); and 72% did not have formal education. Fourteen percent were educated to primary level and only 15% had at least a secondary level. More than half of women were multiparous (52%) only 11% was secundiparous and 37% primiparous. We noted that 90.4% of women slept under ITN last night prior the survey and 73.8% were residents of rural areas and 36.8% lived in households in the lowest wealth tercile (Table 1). Among 2376 interviewed women, 94.6% reported attending ANC at least once during their most recent pregnancy in the past 2 years. The number of ANC visits varied from 1–5 with a median of 1 visit. Among ANC attendees, 43.4% had their first visit in the second trimester. Approximately 5% of the ANC attendees completed at least 3 visits.

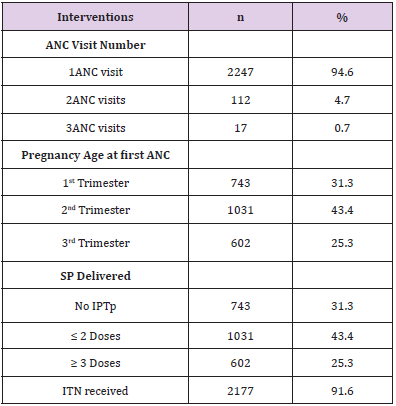

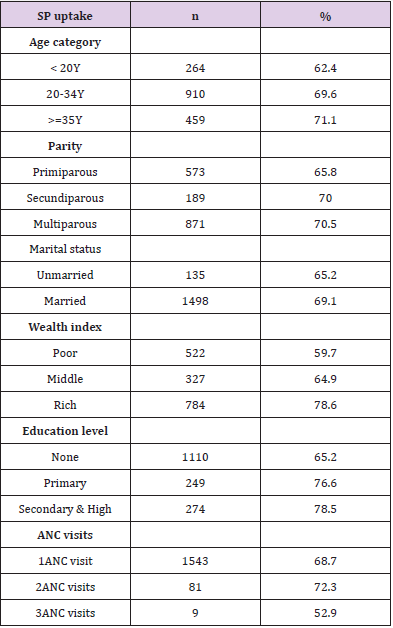

Two-thirds of the study population received at least one dose of IPTp-SP (68.7%), among those 63.1% (1031/1633) received at least 2 doses and 36.9% (602/1633) at least 3 doses. ITNs were provided to 91.6% of participants during ANC visits (Table 2). Women 20- 34 years of age (69.6%) and those older than 35 years (71.1%) were more likely to use IPTp than were younger women under 20 years (OR=1.38[1.09-1.73] p=0.005, OR=1.47 [1.13-1.91] p=0.003, respectively). Multiparous (70.5%), had significantly more chance to have IPTp compared to Primiparous (65.8%, OR=1.24[1.03- 1.48] p=0.0.2) However, married and unmarried women reported 69.1% and 65.2% for SP uptake there was no significant difference (p=0.25). Women from the wealthiest households received more IPTp-SP (78.6%) compared to those from households in the middle wealth strata (64.9%, OR=1.9 [1.5-2.5] p<10-4,) and those in the poorest households (59.7%, p<10-4, OR=2.4[2.03-3.04]). The proportion of women receiving IPTp-SP increased with women’s educational level; those without formal education were least likely to receive IPTp (65.2%) compared to those with a primary level education (76.6%)(p<0.005, OR=1.7 [1.3-2.3]) and those with a secondary level or education of higher (78.5%)( p<0.005, OR=1.9 [1.4-2.5]) .

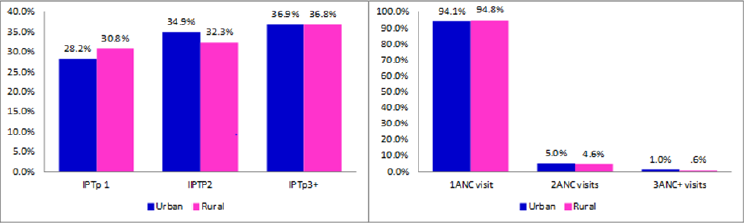

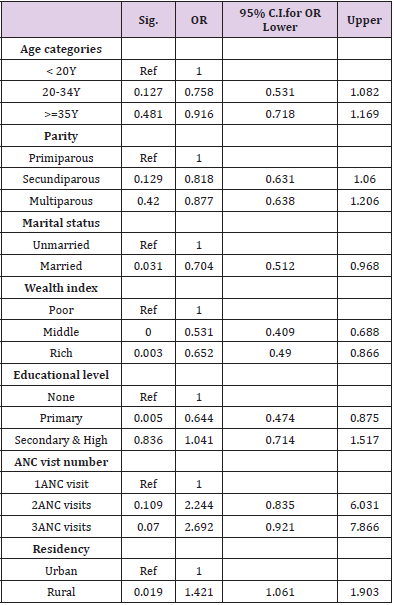

Among women attending their first ANC visit, 68.7% received IPTp-SP, this proportion increased to 72.3% at second ANC visit (p=0.6) and decreased to 52.9% at third ANC visit (p=0.16) (Table 3). Women received 1dose uptake rate was 30.8% in rural area and 28.2% in urban area. Urban women were more likely to get IPTp-SP 2 doses (34.9%) than rural women (32.3%), similar rate was found, 36.9% and 36.8% repectively for urban and rural area for IPTp-SP three doses (Figure 1). First ANC visit was more frequent in urban women (94.1%) and rural women (94.8%) than other 2 and + ANC visits (Figure 1). In multivariate analysis, marital status (married) (p=0.031) wealth index (P <0.005), primary education level (P <10- 4) and rural residency (p=0.019) remained significant independent factors associated with SP uptake (Table 4).

Discussion

This study assessed the determinants of IPTp-SP uptake among Malian women between 15-49 years of old with a live birth in the two years preceding the survey to identify facilitating factors for scaling up IPTp-SP coverage/dosage through the country. Also, the study examined the association between SP uptake and ANC attendance. The study shows that 68% of eligible women received IPTp-SP among those 63.1% at least 2 doses and 36.9% at least 3 doses. Similar findings were reported in Cameroon by [10]: 90% of women had IPTp with at least one SP dose and 53% with 2 doses of SP [10]. In Mali, the last DHS in 2012 found a low coverage of IPTp-SP 2 doses regimen (19.9%) through a large houshold survey despite free IPTp-SP delivery provided to the mothers according national malariacontrol program guidelines [11].

This can be explained by the country’s political, social and security troubles and frequent SP stock outs. Sometime health centers lack qualified health professionals (physician, midwife and obstrtrician nurse) which leads to fewer ANC visits: delivery services costs are the main barrier to access interventions during pregnancy. Hurley et al. suggested in the same country, for increasing IPTp-SP coverage, authorities should invest in efforts to increase ANC attendance as a priority [12]. Other African studies report a range of IPTp 2+ coverage; 42.0 % in Uganda; 47.7% in Sekondi-Takoradi, Ghana, 57.4% in Gabon, 57.6% in Burkina and 68.4% in Benin [13-16]. These studies show that the RBM goal of 80% of women with 2-dose IPTp-SP during pregnancy is not achieved. Elsewhere in Tanzania high rate of IPTp-SP was observed, Protas et al. reported 96% of overall IPTp-SP coverage and 86% of IPTp-SP 2-dose [17].

Among women attending their first ANC visit, 68.7% received IPTp-SP, this proportion increased to 72.3% at second ANC visit (p=0.6). Hill and al. in Kenya reported 59% and 57% of SP uptake in first and second ANC respectively [18]. Education, knowledge about malaria/IPTp and socio-economic status, gestational age and perceptions about SP side effects could be some determinants for the number and timing of antenatal clinic visits [19]. We observed proportions of 94.6% and 5.4% of women who had attending ANC at least once and twice during their last pregnancy respectively. About timing of ANC, 43.4% had their first visit in the second trimester and 31.3% started ANC during the first trimester. The low attendance of ANC can be due to care provider’s attitudes and accessibility (distance and cost), waiting times, quality of care, and perceptions of preventative care and medical interventions during pregnancy. These factors were found to be important in a study by Adrew [20].

In Papua New Guinea. We identified foctors associated with SP uptake in multivariate analysis, among those, marital status, wealth index, primary education level and rural residency remained significantly independent factors. Many studies confirmed this finding [21-24], to increase the level of uptake of IPTp2, appropriate measures should be implemented such as health education and focusing intervention on marginalized population (less wealthy, less educated). Pregnant women’s perceptions about side effects of SP and access to health services may be limiting factors.

References

- Steketee RW, Nahlen BL, Parise ME (2001) The burden of malaria in pregnancy in malaria-endemic areas. Am J Trop Med Hyg 64(1-2 Suppl): 28-35.

- (2004) WHO. A strategic framework for malaria prevention and control during pregnancy in the African region Brazzaville: World Health Organization: Regional Office for Africa?

- Hill J, Hoyt J, Van Eijk AM (2013) Factors affecting the delivery, access, and use of interventions to prevent malaria in pregnancy in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 10(7): e1001488.

- Van Eijk AM, Hill J, Alegana VA (2011) Coverage of malaria protection in pregnant women in sub-Saharan Africa: a synthesis and analysis of national survey data. Lancet Infect Dis 11(3): 190-207.

- Ndyomugyenyi R, Neema S and Magnussen P (1998) The use of formal and informal services for antenatal care and malaria treatment in rural Uganda. Health Policy Plan 13(1): 94-102.

- Holtz TH, Kachur SP, Roberts JM, Meredith C Klein, Samba I Diop (2004) Use of antenatal care services and intermittent preventive treatment for malaria among pregnant women in Blantyre District, Malawi. Trop Med Int Health 9(1): 77-82.

- Mubyazi G, Bloch P, Kamugisha M (2005) Intermittent preventive treatment of malaria during pregnancy: a qualitative study of knowledge, attitudes and practices of district health managers, antenatal care staff and pregnant women in Korogwe District, North-Eastern Tanzania. Malar J 4: 31.

- Bouyou-Akotet MK, Mawili Mboumba DP, Kombila M (2013) Antenatal care visit attendance, intermittent preventive treatment and bed net use during pregnancy in Gabon. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 13: 52.

- Crawley J, Hill J, Yartey J (2007) From evidence to action? Challenges to policy change and programme delivery for malaria in pregnancy. Lancet Infect Dis 7(2): 145-155.

- Anchang Kimbi JK, Achidi EA, Apinjoh TO, Hanesh Fru Chi, Rolland B, et al. (2014) Antenatal care visit attendance, intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy (IPTp) and malaria parasitaemia at delivery. Malar J 13: 162.

- DHS (2014) Demographic and Health Survey 2012-2013 (DHS-V).

- Hurley EA, Harvey SA, Rao N (2016) Underreporting and Missed Opportunities for Uptake of Intermittent Preventative Treatment of Malaria in Pregnancy (IPTp) in Mali. PLoS One 11(8): e0160008.

- Sirima SB, Cotte AH, Konate A, Monica E Parise, Robert D Newman, et al. (2006) Malaria prevention during pregnancy: assessing the disease burden one year after implementing a program of intermittent preventive treatment in Koupela District, Burkina Faso. Am J Trop Med Hyg 75(2): 205-211.

- Almeida TC, Agboton Zoumenou MA, Garcia A (2011) Field evaluation of the intermittent preventive treatment of malaria during pregnancy (IPTp) in Benin: evolution of the coverage rate since its implementation. Parasit Vectors 4: 108.

- Muhumuza E, Namuhani N, Balugaba BE (2016) Factors associated with use of malaria control interventions by pregnant women in Buwunga subcounty, Bugiri District. Malar J 15(1): 342.

- Orish VN, Onyeabor OS, Boampong JN (2016) Prevalence of intermittent preventive treatment with sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine (IPTp-SP) use during pregnancy and other associated factors in Sekondi-Takoradi, Ghana. Afr Health Sci 15(4): 1087-1096.

- Protas J, Tarimo D, Moshiro C (2016) Determinants of timely uptake of ITN and SP (IPT) and pregnancy time protected against malaria in Bukoba, Tanzania. BMC Res Notes 9: 318.

- Hill J, Dellicour S, Bruce J, James Smedley, Peter Otieno, et al. (2013) Effectiveness of antenatal clinics to deliver intermittent preventive treatment and insecticide treated nets for the control of malaria in pregnancy in Kenya. PLoS One 8(6): e64913.

- Webster J, Kayentao K, Diarra S (2013) A qualitative health systems effectiveness analysis of the prevention of malaria in pregnancy with intermittent preventive treatment and insecticide treated nets in Mali. PLoS One 8(7): e65437.

- Andrew EV, Pell C, Angwin A (2014) Factors affecting attendance at and timing of formal antenatal care: results from a qualitative study in Madang, Papua New Guinea. PLoS One 9(5): e93025.

- Van Eijk AM, Hill J, Larsen DA (2009) Coverage of intermittent preventive treatment and insecticide-treated nets for the control of malaria during pregnancy in sub-Saharan Africa: a synthesis and meta-analysis of national survey data, 2009-11. Lancet Infect Dis 13(12): 1029-1042.

- Hill J, Kayentao K, Achieng F, Stephanie Dellicour, Sory I Diawara, et al. (2015) Access and Use of Interventions to Prevent and Treat Malaria among Pregnant Women in Kenya and Mali: A Qualitative Study. PLoS One 10(3): e0119848.

- Hill J, Kayentao K, Toure M (2014) Effectiveness of antenatal clinics to deliver intermittent preventive treatment and insecticide treated nets for the control of malaria in pregnancy in Mali: a household survey. PLoS One 9(3): e92102.

- Hill J, Kazembe P (2006) Reaching the Abuja target for intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy in African women: a review of progress and operational challenges. Trop Med Int Health 11(4): 409-418.

Research Article

Research Article