Abstract

Objectives: To assess gender differences in the treatment and outcomes of patients with ACS in the CZECH national registry. To evaluate the impact of national reperfusion network on care of women with ACS.

METHODS: 1921 patients hospitalized for suspected ACS were enrolled into the CZECH registry in November 2005. In-hospital outcomes were compared by gender.

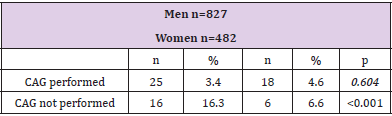

Results: 788 women were enrolled. The diagnosis of ACS was confirmed in 62.3% women compared to 76.4% men (p<0.001). Women were older (age 71+10.4 vs.64+11.6 years; p<0.001), had significantly higher rates of hypertension (77.2% vs.65.4%; p<0.001), and diabetes (40.9% vs.25.5%; p<0.001). They had significantly lower rates of prior myocardial infarction (24.3% vs.30.8%; p=0.01) and were less likely ever to have smoked (18.9% vs.30.3%, p<0.001). The rates of in-hospital coronary angiography and following revascularization procedures were lower in women (79.9% vs.85.7%; p=0.006 and 67% vs.76%; p<0.001 respectively). However, more women did not have significant coronary stenosis in comparison to men (6.1% vs.1.9%; p=0.01). Overal mortality was equal in men and women (both 5.0%), occurrence of MACE (23.6 vs.24.9%). The mortality of women and men was 5.2% vs.3.0% (p=0.086) when treated with revascularisation and 6.6% vs.16.3% (p<0,001) when treated conservatively.

Conclusion: Women with ACS have different clinical characteristics and are less often referred to revascularisation therapy. Similar outcome was observed in both genders, but with conservative treatment the women showed better prognosis then men.

Abbreviations: ACS: Acute Coronary Syndrome; CABG: Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery; CAD: Coronary Artery Disease; CAG: Coronary Angiography; CK-MB: Creatine Kinase-MB Isoenzyme; LMCA: Left Main Coronary Artery; MACE: Major Adverse Cardiac Events; MI:Myocardial Infarction; NSTEMI: Non- ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction; PCI: Percutaneous Coronary Intervention; STEMI: ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction; UAP: Unstable Angina Pectoris

Introduction

Coronary Artery Disease (CAD) has been considered for many years a men’s disease. According to recent data, it actually represents the leading cause of death among women in the industrialized countries. The number of females among patients presenting with Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS) is rising. Studies have shown significant gender difference in the presentation, treatment and outcome of patients with ACS [1-3]. Some investigators have reported that women with ACS are diagnosed later than men and receive less invasive cardiac procedures [1]. It has also been reported that women tend to decline certain diagnostic and therapeutic options [4], as well as that physicians are biased when treating in regard to current guidelines [5]. The general perception is that Coronary Artery Disease (CAD) has been considered for many years a men’s disease. According to recent data, it actually represents the leading cause of death among women in the industrialized countries. The number of females among patients presenting with Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS) is rising. Studies have shown significant gender difference in the presentation, treatment and outcome of patients with ACS [1-3]. Some investigators have reported that women with ACS are diagnosed later than men and receive less invasive cardiac procedures [1]. It has also been reported that women tend to decline certain diagnostic and therapeutic options [4], as well as that physicians are biased when treating in regard to current guidelines [5]. The general perception is that

Methods

An analysis of data from the CZECH (Czech evaluation of acute coronary syndromes in hospitalized patients) registry was performed. The details of the registry were reported in prior publication [8]. This registry collected data in two arms. The first arm “The regional registry» included all hospitals (n=17) in two Czech counties with a total population of 1 053 267 inhabitants. The second arm “The PCI centers registry» included all 21 Czech PCI centers serving to the mean number of 488 095 inhabitants.

Patients

The entry criterion to this registry was hospital admission for suspected ACS within 1 month (November 2005). A total of 1921 patients, 788 (41%) women and 1,133 men, were enrolled, mean age, 66 years; age range 22–94 years. Discharge diagnosis of ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI) was based on occurrence of ST elevations on ECG in at least 2 contiguous leads and elevation of CKMB. Non ST Elevations Myocardial Infarction (NSTEMI) diagnosis was based on serial rise and fall of CKMB and/or troponin I. Unstable Angina Pectoris (UAP) was diagnosed in chest pain patients, when troponin and CKMB were repeatedly negative and evidence of significant coronary artery disease was present. Any of these three forms of acute coronary syndrome were confirmed as the final (discharge) diagnosis in 1345 (70%) patients.

Data Collection and Analysis

Data of each patient were entered into a specifically designed 168-item case report form. The data were finally transferred into a central database, which was the basis for the specific information provided here. The Major Adverse Cardiac Events (MACE) - the death, re-infarction, stroke, heart failure, target vessel revascularisation and malignant arrhythmias were evaluated. Baseline characteristics, medical and coronary interventions, and clinical outcomes were compared between women and men. For comparisons of continuous variables, linear regression was used, and for comparisons of categorical values, logistic regression was used. Comparisons between women and men were adjusted for differences in baseline factors, which influence clinical outcomes including age, diabetes and history of cardiovascular disease. Logistic regression models were used for crude as well as adjusted analyses of in-hospital mortality. Multivariable models were constructed to determine the predictive value of gender on clinical outcomes. Of the 1345 patients with confirmed ACS, 1309 patients with complete data could be used for the analysis.The incidence was calculated only from the “regional arm” of this registry due to the fact, that this arm was organized to cover 100% of hospitalized patients (all existing hospitals) in a region with well-defined population.

Results

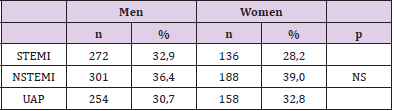

At discharge, the diagnosis of ACS was less frequently confirmed among women in comparison to men 62.3% vs. 75.4%, (p<0.001) in the whole studied group. In the regional registry the ACS was confirmed in only 43.2% of women vs. 57.4% of men (p=0.006). In the PCI centers registry only 35.6% of enrolled patients with ACS were women, while in regional registry there were 43.7% of women. Among the patients with confirmed ACS the diagnosis of STEMI, NSTEMI and UAP was similarly frequent in women and men 28.2% vs. 32.9%, 39.0% vs. 36.4% and 32.8% vs. 30.7% (p=0.2) respectively (Table 1). Incidence of acute coronary syndromes in women: The calculated annual incidence of hospitalized confirmed ACS (STEMI, NSTEMI or UAP) in women was slightly lower compared to men, 1419 vs. 1828 patients per million inhabitants. The annual incidence of hospitalized, confirmed acute myocardial infarction (i.e., any type of infarction, without UAP patients) was 857 in women compared to 1103 in men per million inhabitants; the annual incidence of STEMI was 289 in women and 372 in men per million inhabitants.

Table 1: Representation of confirmed ACS types in men and women.

Note: STEMI = ST elevation myocardial infarction, NSTEMI = Non ST elevations myocardial infarction, UAP = unstable angina pectoris

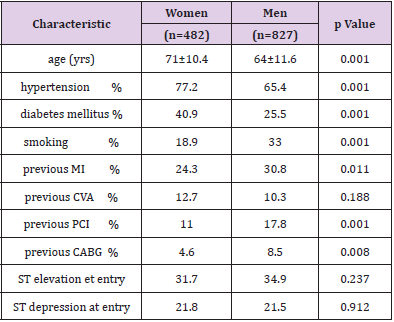

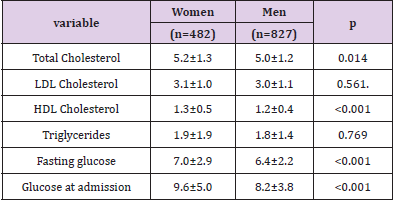

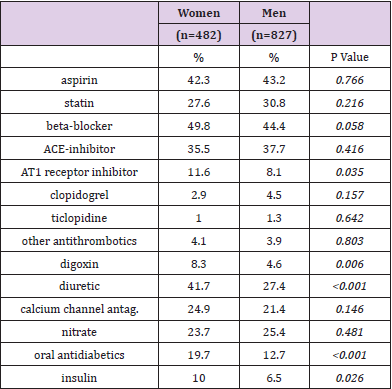

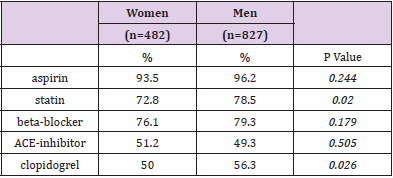

Baseline characteristics: The women were older than men and were more likely to have diabetes, hypertension and elevated total cholesterol levels. They were less likely ever to have smoked and less likely to have a history of myocardial infarction, angioplasty, or bypass surgery.At admission, there was no difference in the rate of ST segment elevations or depressions on electrocardiogram between women and men. Higher fasting glucose and admission glucose levels in females were in concordance with their more frequent diabetes (Tables 2&3). Pharmacotherapy: At hospital admission, no differences in the use of aspirin, statins, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, or beta-blockers between women and men were observed, although women were more likely to be treated with diuretics, dioxin, angiotensin I blockers, oral antidiabetics and with insulin (Table 4). During the initial hospitalization, the use of aspirin, statins, beta-blockers, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor medications increased significantly among all patients. On discharge, the only significant difference in medication was the higher prescription rates of statins and clopidogrel in men (Table 5).

Table 2: Baseline Patient Characteristics.

Note: Data are expressed as mean or percentage (95% confidence interval).

CABG = coronary artery bypass grafting; CVA= stroke; PCI = coronary angioplasty; MI = myocardial infarction.

Table 3: Blood lipids and glucose.

Note: Data are expressed in mmol/l as mean (95% confidence interval).

Table 4: Medication before admission.

Note: Data are expressed as mean or percentage (95% confidence interval).

Table 5: Medication on discharge.

Note: Data are expressed as mean or percentage (95% confidence interval).

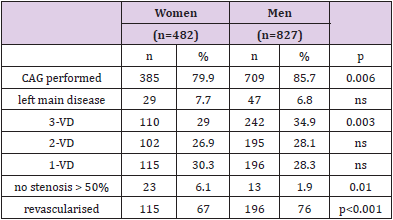

Invasive procedures: Coronary Angiography (CAG) was performed during the initial hospitalization in 1094 (83.5%) of patients with confirmed ACS. Fewer women underwent CAG when compared to men (79.9% vs. 85.7%; p=0.006). The difference was driven mainly by patients with NSTE-ACS, while among patients with STEMI the CAG was performed in high number of both men and women. Among patients with unconfirmed ACS the coronary angiography was performed similarly in 41.4% of men and 35.4% (p=0.13) of women. The rates of coronary angiography among men and women in peripheral registry were 49% vs. 38%, in PCI registry 94% vs. 90.2%. There were more patients without significant coronary stenosis among the women (6.1% vs. 1.9%; p=0.01). Men had more severe coronary disease with more prevalent three vessel involvement (34.9% vs. 29.0%; p=0.003). The incidence of left main disease was similar in both genders (Table 6).

Table 6: Invasive procedures and angiographic characteristics.

Note: CAG – coronary angiography, 3-VD – 3 vessel disease.

All together, 73% of patients underwent revascularization. Revascularization procedures were less frequent in women compared to men 67.2 % vs. 76.3 %; p<0.001. Among patients with coronary angiography the gender difference disappeared, as 84% women vs. 89% men (p=0.097) were revascularised. Percutaneous coronary intervention was the first and, in most cases, the only intervention in almost 90% of revascularised patients of both genders. PCI to CABG ratio was 8:1 in women. Of 324 revascularised women 272 (84%) had PCI, 37 (11%) CABG. 15 patients (5%) received both procedures. The proportion of men who underwent PCI, CABG or both was similar (83%, 13% and 4% respectively, p=0.839). Coronary angiography and subsequent coronary stenting of the culprit lesion as the primary revascularization method were performed within 3 days of admission in most patients.Reperfusion therapy for STEMI: CAG was performed upon admission almost equaly in 93.1% of women vs. 95.1% of men with ST-elevations (p=0.39). Immediate primary PCI followed in 85% women and in 89.3% men (p=0.29); emergent Coronary Artery Bypass Graft (CABG) was performed in 2.5% of both women and men with STEMI. Thus, invasive reperfusion therapy was used in 87.5% of women and in 91.8% of men with STEMI (p=0.135). Interventions for non-STE ACS: In-hospital coronary angiography was performed in 84.3% of women and 88.9% (p=0.2) of men with NSTEMI, followed with PCI in 53.9% of women and 59.4 of men (p=0.3). CABG was performed similarly in 13.7% of women and in 15% of men. Among UAP patients, coronary angiography was undertaken in 73.8% of women and in 84.4% of men (p=0.008), followed by PCI in 53.9% women, 68% men (p=0.193). CABG was performed in 15.8% men and 13.7% women.

Outcomes

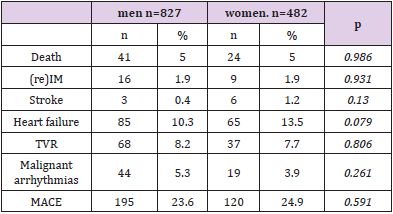

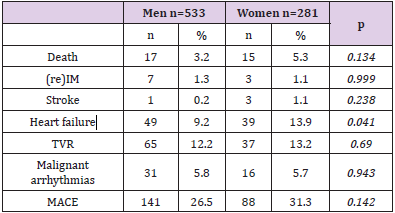

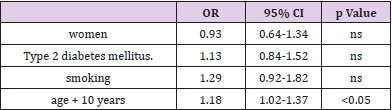

Total in-hospital mortality of all patients with confirmed ACS was 5.0%; the incidence of nonfatal recurrent MI was 1.9%, both in women and men. The incidence of all Major Adverse Cardiac Events (MACE) was similar in men and women, 23.6% vs. 24.9% (Table 7). In the subgroups of patients with STEMI, NSTEMI and UAP the inhospital mortality in women and men was 11.3% vs 7.1% (p=0.13), 1.0% vs. 5.0% (p=0.15) and 2.0% vs 1.1% (p=0.75) respectively. Among patients treated with PCI the in-hospital mortality of women was 5.3% compared to 3.2% mortality of men (p=0.134); women had higher incidence of in-hospital acute heart failure (13.9% vs 9.2%, p=0.041). The incidence of other major adverse cardiac events (re-infarction, stroke, target vessel revascularization, serious arrhythmias) was similar in women and men treated with PCI, (Table 8). Mortality of women treated with CABG was 3.9% compared to 2.9% mortality of men (p=0.9), (Table 9). Mortality of women treated with any revascularisation was 5.2% compared to 3.0% mortality of men (p=0.086). Mortality of women treated conservatively (with medical treatment) was 6.6% compared to 16.3% mortality of men (p<0,001), (Table 10). In the multivariate analysis gender was not found to be an independent risk factor for MACE when adjusted for baseline variables (Table 11). Even, if the presence or absence of significant stenosis after angiography was also included in the statistical model, female gender was not found to be an independent risk factor for death or MI.

Table 11: InMultivariate relationship between the risk of MACE and variables (adjusted to age. BSA and BMI).

Discussion

Incidence: As in other population-based studies in the CZECH registry we have observed the higher incidence of an acute coronary syndrome among men compared to women. But the difference is small confirming the increasing number of women with ACS. We demonstrate that among patients who present with symptoms suggestive of cardiac ischemia, ACS is confirmed more often in men than in women. Some randomized studies, reported lower proportion of women among patients who had STEMI, compared to patients with other acute ischemic syndromes [9-12]. Among patients with myocardial infarction women presented more often with NSTEMI. Furthermore in some studies the ratio of men to women with a NSTEMI was significantly greater than in patients with unstable angina [10]. In our registry, these differences were not significant. This may indicate that the sex ratios in randomized clinical trials may be biased, as women might be more often excluded from reperfusion treatment of AMI [10].Baseline characteristics: Patients with ACS in our registry showed differences in baseline clinical characteristics between women and men. We confirm findings of multiple studies [1,2,11-27] which have shown that women with acute ischemic syndromes are older than men and are more likely to have a history of hypertension, diabetes, and congestive heart failure. Women are less likelyto be smokers and less likely to have had a prior MI, CABG or PCI. Pharmacotherapy: Several centers have reported gender differences in the medical treatment of cardiovascular disease, to the detriment of women [17]. Fewer women were prescribed beta-blockers for ACS in some studies [13,14]. We found the medical management of men and women with ACS similar, but fewer women were prescribed statins at the time of discharge despite of their higher levels of cholesterol compared to men. Lower use of clopidogrel in women corresponds with lower use of PCI but these findings may indicate lower adherence to guidelines when treating women with ACS. More women were taking digoxin and diuretics at the time of admission. This fact is probably due to the greater proportion of women with hypertension and heart failure.

Angiographic characteristics: Similarly as in many studies [14,25,27] but in contrast to some other reports [18] we observed less severe angiographic extent of CAD and higher rates of clinically insignificant CAD among women with confirmed ACS [10]. The reason for the later finding could be more frequent coronary spasms or thrombosis on insignificant coronary plaque but also more frequent false diagnosis of ACS in women. Among those with significant coronary lesions, we found a lower rate of twoor three-vessel disease in women compared with men, which is also a common phenomenon in groups of patients with coronary heart disease [27]. These findings favoring women may be counterbalanced with smaller vessels and with other risk factors.

Invasive procedures: Frequently reported less aggressive therapy of ACS in women as compared to men can be a result of the general perception that women are at lower risk for heart disease and of uncertainty whether women with ACS benefit from the invasive treatment strategy as it is among men. This may negatively impact the management of high-risk women. As in other studies [14,19,27-32] we found lower probability for women to be referred to CAG and subsequently to revascularization procedures. Conservative therapy was more frequent in women.

The gender difference found in our study was mainly due to the lower rate of CAG among women with unstable angina and among women with any NSTE-ACS enrolled into regional registry. In PCI centers registry there was no gender difference in the use of invasive approach observed. Lower representation of women (35.6%) in PCI centers registry compared to peripheral registry (43.7%) also indicates that women are less likely than men to be referred to invasive investigation. The possible explanation for this gender difference include women’s older age at presentation, greater risk profile, increased risk for an adverse procedural outcome, differences in symptoms and pain perception, lower predictive accuracy of noninvasive testing in women, patient preferences to undergo invasive procedures [5,20], physicians biases when dealing with women and physicians gender specific practices in the referral of women for cardiac catheterization [20]. Significantly fewer women underwent PTCA or CABG surgery. However once women were referred for cardiac catheterization, revascularization rates were similar to those in men, which is finding consistent with other studies. Among patients who were identified as having significant CAD on angiography, the proportion of patients who underwent PCTA or CABG was equal in both genders, which was also found in previous studies [14,19]. Among patients with STEMI the use of coronary angiography was high and in contrast to some studies [21] we have found no gender specific difference in the use of invasive procedures.

Outcomes

Evidence about the outcome of ACS in women is conflicting. Some reports have concluded that women have a worse prognosis in comparison to men [1,17]. It is not clear whether this observation reflected differences in baseline characteristics [2,10], gender related pathophysiology [22] or differences in the diagnosis and treatment of ACS in men and women [21]. Reduced collateral blood flow in women might account for the higher rate of complications when coronary occlusion occurs. Some studies have attributed the worse prognosis of women to the older age, to the higher prevalence of arterial hypertension and diabetes. Other studies have found that the difference in mortality rate was independent of these factors. Furthermore more recent studies have found similar outcome in both genders [11] or even better prognosis for women with ACS [27].In our study the overall mortality of patients with any ACS was equal in men and women. Among STEMI patients the most of studies observed a higher early mortality in women compared to men [2,12,23-25,29]. Some studies report, that primary PCI may eliminate these gender-specific differences in survival [31]. In our study 87% of patients with STEMI underwent primary PCI. There was only insignificant gender difference in hospital mortality in favor of men observed in this subgroup, 11.3% vs. 7.1%, (p=0,13).

With regard to NSTE-ACS, the existing evidence is contradictory. Some studies have demonstrated similar outcomes of women and men [10,26] with no difference in the incidence of cardiovascular death, recurrent MI, or stroke [14]. In FRISC II study there was a trend toward a more severe outcome in the female group with NSTE-ACS, but in the multivariate analysis gender was not found to be an independent risk factor when adjusting for the baseline variables [13]. However, if the presence or absence of significant stenosis after angiography was also included in the statistical model, female gender was found to be an independent risk factor for death or MI [13]. In contrast Mueller found that women treated with very early aggressive revascularization with coronary stenting of the culprit lesion have a better long-term outcome as compared with men. In multivariate analysis he has found, that female gender reduced the risk of death or MI by 49% [27]. Among patients with unstable angina, female sex may even be associated with an independent protective effect [2]. We observed a trend to lower mortality of women with NSTEMI, (1.0% vs. 5.0%; p=0.15). Women in our study were more likely than men to have congestive heart failure during hospitalization, as was also found in several previous studies [12,28]. This finding may be related to the fact that higher percentage of women have a history of heart failure at presentation, and it may also reflect diastolic dysfunction being more pronounced in women [10].

Invasive versus conservative treatment: Important discussion continues about whether different outcomes exist for women with use of a routine invasive or selective invasive management strategy. Some doubts have been raised whether the management of women and men with ACS should be similar. Female gender was reported to be risk factor for mortality and morbidity for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI) [29] and CABG [30]. Although in some studies the worse prognosis of women after cardiac interventions disappeared after adjustment to risk factors [31]. Analyses of The FRISC II [13], RITA-3 [15] randomized clinical trials found that women had less profit from an early invasive strategy in comparison to men. In RITA-3 study it appeared that women with ACS at lower risk and those with negative troponin levels tend to have excess of adverse events with invasive strategy. In FRISC II the prognosis of women was better than men in the conservative treatment group, while in the invasive treatment group in the presence of significant coronary stenosis the female gender was found to be independent risk factor for death and MI. The results from the mentioned trials conflict with the results of TACTICS-TIMI 18 trial in which women appeared to benefit as much as men from an early invasive strategy [16]. This is supported by the results of CRUSADE prospective registry in which women who were 14% less likely to receive early invasive management after ACS had a significantly higher in-hospital mortality with early conservative treatment (no early invasive vs. early invasive: 8.9% vs. 4.7%) [32]. Another study reports that aggressive revascularization offers a comparable survival benefit for both genders [11]. Mueller in his study even found that invasive treatment with PCI was associated with a significantly better outcome in women as compared with men with ACS [27].

The worse outcome of invasively treated women in FRISC seemed to be solely due to an excess hazard ratio in women undergoing CABG, as PCI to CABG ratio was 1:1 [13]. Therefore, the PCI: CABG ratio of the revascularization strategy might be an important contributor to gender differences in the outcome of patients with NSTE-ACS. Low rate of CABG in our group (PCI: CABG ratio was 8:1) may play role in favorable outcomes of invasively treated women. The seven days interval for invasive treatment in FRISC may be too long. Mueller found that women treated with very early aggressive revascularization with coronary stenting of the culprit lesion as the primary revascularization strategy have a better long-term outcome in comparison to men [27].

In our group the coronary angiography and subsequent coronary stenting of the culprit lesion as the primary revascularization method were performed within 3 days of admission in most patients. This treatment was associated with comparable outcome in women as compared to men.We observed a trend to higher inhospital mortality of women compared to men with early invasive treatment. Among patients with conservative treatment women’s mortality was significantly lower then mortality of men. While the prognosis of women treated with invasive or conservative strategy did not differ, men treated conservatively had much worse prognosis compared to men treated invasively. Our results support the idea that early invasive strategy in women may be less advantageous then in men.

Study Limitations

Our analysis is derived from a prospective study of consecutive unselected patients rather than a randomized trial, but this may be particular valuable for the investigation of gender-based differences. Non-randomized study eliminates selection bias and eases the extrapolation of findings into clinical practice. Women are notoriously underrepresented in randomized controlled trials [27] of ACS. The numbers of patients are small to draw final conclusions.

Conclusion

Women are less often than men hospitalized for suspected ACS. Among those hospitalized and screened, the female gender predicts lower probability of ACS confirmation. Women with ACS have less advanced atherosclerosis, but often have important comorbidities associated with an increased invasive procedurerelated risk. Compared to men, women with ACS undergo less coronary angiography, angioplasty, and CABG surgery. Women suffer an increased rate of heart failure during hospitalization. Although in many studies women with ACS consistently tend to have worse clinical outcomes, we observed indeed comparable outcomes in both genders in spite of higher risk profile of women. Our results may reflect recent advances in angioplasty equipment which improved options for patients with smaller coronary and peripheral (access) arteries. In addition, the increased use of stents and adjunctive pharmacotherapy has improved outcomes in both women and men. Our study confirms that aggressive revascularization offers a comparable survival in the two sexes with satisfactory in-hospital outcomes. Treatment with the early angioplasty and coronary stenting of the culprit lesion gives satisfactory in-hospital results. While the prognosis of women treated with invasive and conservative strategy was equal, the prognosis of conservatively treated men was much worse. The men with NSTE-ACS seem to benefit more then women from the early invasive treatment.

Acknowledgement

This registry was organized by the Czech Society of Cardiology and was supported by an unrestricted grant from Sanofi-Aventis Czech Republic. Support for this analysis was provided by the Charles University Research Project MSM0021620817. The registry was approved by the local ethical committees of all participating hospitals Appendix.

References

- Radovanovic D, Erne P, Urban P, Bertel O, Rickli H, et al. (2007) Gender differences in management and outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes: results on 20,290 patients from the AMIS Plus Registry. Heart 93(11): 1369-1375.

- Hochman JS, Tamis JE, Thompson TD, Weaver WD, White HD, et al. (1999) Sex, clinical presentation, and outcome in patients with acute coronary syndromes. NEJM 341(4): 226-232.

- Devon HA, Zerwic JJ (2002) Symptoms of acute coronary syndromes: are there gender differences? A review of the literature. Heart Lung 31(4): 235-345.

- Ghali WA, Faris PD, Galbraith PD, Norris CM, Curtis MJ, et al. (2002) Sex differences in access to coronary revascularization after cardiac catheterization: importance of detailed clinical data. Ann Int med 136: 723-732.

- Heidenreich PA, Shlipak MG, Geppert J, Clellan MK (2002) Racial and sex differences in refusal of coronary angiography. Am J Med 113: 200-207.

- Khaw KT (2006) Epidemiology of coronary heart disease in women. Heart 92(suppl 3): iii2-iii4.

- Widimsky P, Budesinsky T, Vorac D, Groch L, Zelizko M, et al. (2003) Long distance transport for primary angioplasty vs immediate thrombolysis in acute myocardial infarction. Final results of the randomized national multicentre trial-PRAGUE-2. Eur Heart J Jan 24(1): 94-104.

- Widimsky P, Zelizko M, Jansky P, Tousek F, Holm F, et al. (2007) The incidence, treatment strategies and outcomes of acute coronary syndromes in the ”reperfusion network” of different hospital types in the Czech Republic: Results of the Czech evaluation of acute coronary syndromes in hospitalized patients (CZECH) registry. Int J Cardiol 119: 212–219.

- Stone GW, Grines CL, Browne KF, Marco L, Rothbaum D, et al. (1995) Comparison of in-hospital outcome in men versus women treated by either thrombolytic therapy or primary coronary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 75: 987-992.

- Hochman JS, Mc Cabe CH, Stone PH, Becker RC, Cannon CP, et al. (1997) Outcome and profile of women and men presenting with acute coronary syndromes: a report from TIMI IIIB. J Am Coll Cardiol 30: 141-148.

- Bounhoure JP, Farah B, Fajadet J, Marco J (2004) Prognosis after acute coronary syndrome. Lack of difference according to the sex. Bull Acad Natl Med 188(3): 383-397.

- Weaver WD, White HD, Wilcox RG, Aylward PE, Morris D, et al. (1996) Comparisons of characteristics and outcomes among women and men with acute myocardial infarction treated with thrombolytic therapy. JAMA 275: 777-782.

- Lagerquist B, Säfström K, Ståhle E, Wallentin L, Swahn, et al. (2001) Is early invasive treatment of unstable coronary artery disease equally effective for both women and men? J Am Coll Cardiol 38: 41-48.

- Anand SS, Chung Xie Ch, Mehta S, Franzosi MG, Joyner C, et al. (2005) Differences in the management and prognosis of women and men who suffer from acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol 46: 1845-1851.

- Fox KA, Poole-Wilson PA, Henderson RA, Clayton TC, Chamberlain DA, et al. (2002) Interventional versus conservative treatment for patients with unstable angina or non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction: the British Heart Foundation RITA 3 randomized trial. Randomized Intervention Trial of unstable Angina. Lancet 360: 743-751.

- Glaser R, Herrmann HC, Murphy SA, Demopoulos LA, DiBattiste PM, et al. (2002) Benefit of an early invasive management strategy in women with acute coronary syndromes. JAMA 288: 3124-3129.

- Hochman JS, Tamis-Holland JE (2002) Acute coronary syndromes. Does sex matter? JAMA 288: 3161-3164.

- Chua TP, Saia F, Bhardwaj V, Wright C, Clarke D, et al. (2000) Are there gender differences in patients presenting with unstable angina? Int. J Cardiol 72: 281-286.

- Vikman S, Airaksinen KE, Tierala I (2007) Gender-related differences in the management of non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome patients. Scand Cardiovasc J 13: 1-7.

- Rathore SS, Wang Y, Radford MJ, Ordin DL, Krumholz HM (2002) Sex differences in cardiac catheterization after acute myocardial infarction: the role of procedure appropriateness. Ann Intern Med 137: 487-493.

- Stone PH, Thompson B, Anderson HV, Kronenberg MW, Gibson RS, et al. (1996) Influence of race, sex, and age on management of unstable angina ang non Q-wave myocardial infarction: The TIMI III registry. JAMA 275: 1104-1112.

- Levenson J, Pessana F, Gariepy J, Armentano R, Simon A (2001) Gender differences in wall shear-mediated brachial artery vasoconstriction and vasodilatation. J Am Coll Cardiol 38: 1668-1674.

- Kober L, Torp-Pedersen C, Ottesen M, Rasmussen S, Lessing M, et al. (1996) Influence of gender on short- and long-term mortality after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 77: 1052-1056.

- Reina A, Colmenero M, de Hoyos EA, Arós F, Martí H, et al. (2007) Gender differences in management and outcome of patients with acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol 116: 389-395.

- Srinivas VS, Garg S, Negassa A, Bang JY, Monrad ES (2007) Persistent sex difference in hospital outcome following PCI: Results from the New York state reporting system. J Invasive Cardiol 19: 265-268.

- Perers E, Caidahl K, Herlitz J, Karlsson T, Hartford M (2007) Impact of diagnosis and sex on long-term prognosis in acute coronary syndromes. Am Heart J 154(3): 482-488.

- Mueller Ch, Neumann FJ, Roskamm H, Buser P, Hodgson JM, et al. (2002) Women do have an improved long-term outcome after non–ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes treated very early and predominantly with percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol 40: 245-250.

- Maynard C, Litwin PE, Martin JS, Weaver WD (1992) Gender differences in the treatment and outcome of acute myocardial infarction: results from the Myocardial Infarction Triage and Intervention Registry. Arch Intern Med 152: 972-976.

- Malenka DJ, O’Connor GT, Quinton H, Wennberg D, Robb JF, et al. (1996) Differences in outcomes between women and men associated with percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty: a regional prospective study of 13,061 procedures. Circulation 94 Suppl II: II99-II104.

- O’Connor GT, Morton JR, Diehl MJ, Olmstead EM, Coffin LH, et al. (1993) Differences between men and women in hospital mortality associated with coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Circulation 88: 2104-2110.

- Tillmanns H, Waas W, Voss R, Grempels E, Hölschermann H, et al. (2005) Gender differences in the outcome of cardiac interventions. Herz 30(5): 375-389.

- Bhatt DL, Roe MT, Peterson ED, Li Y, Chen AY, et al. (2004) Utilization of early invasive management strategies for high-risk patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Results from the CRUSADE quality improvement initiative. JAMA 292: 2096-2104.

Research Article

Research Article