Abstract

The article undertakes a current topic of healthcare management reform in Poland. After the proposed modifications, the system will be organized as a governance network with a number of interdependent actors. The article presents the network structure and actors as well as analyses its power relations, strength, dependency and effectiveness. The author believes that the new structure should be beneficial to the patients, particularly if the financial and healthcare ratios, as effectiveness measures, will be well-defined.

Keywords: Healthcare Management Reform; Poland; Network of Hospitals; Governance Network

Introduction

Over the years public healthcare in Poland has undergone multi-facet changes in order to improve the quality of services provided to the people. Under-financing has been the root of the healthcare problems for many year, resulting in lack of access to medical professionals and procedures. When looking at statistical data on financing, Poland had one of the lowest healthcare spending of 684 euro per inhabitant with only Croatia (681 euro), Latvia (650 euro), Bulgaria (504 euro) and Romania (388 euro) followed with the lowest spending [1]. The spending is also one of the lowest as a percentage of GDP with only 6.3% [1]. Lack of funds leads governing bodies of public healthcare to propose changes to more efficiently utilize available resources. Over the years there has been a mounting public opinion pressure to provide quality free-of-charge services to all needy patients. This race for increased quality with non-rising financial inputs has caused many changes in public healthcare system in Poland with each new administration making smaller or more sizable changes. The current institutional system has been in place since 2004, although it has neither been free of adjustments. The article aims to present the map of current institutional system of public healthcare in Poland and analyse the proposed changes of the network of hospitals in terms of their benefits to network actors. Modifications proposed to the system are meant to improve the quality of public healthcare services and thus are linked with changes in distribution of public funds.

Literature Overview

Network is a structure composed of “several independent actors involved in delivering services […] made up of organizations which need to exchange resources […] to achieve their objectives, to maximize their influence over outcomes, and to avoid becoming dependent on other players in the game [2]. Therefore, the network structure connects actors which are independent but who by working together, can achieve more or increase the quality of provided services. Governance networks are special types of networks “defined as networks of interdependent actors that contribute to the production of public governance [3]. It follows that provision of public healthcare services falls within the scope of governance networks. Network structure can be characterized by variables such as dependency and strength. Dependency means that actors are in some way dependent upon availability of resources [4]. As literature on networks evolved, the new term of interdependency was coined that refers to common use of physical resources or knowledge [5]. Interdependency requires from actors a form of planning and/or bargaining which makes the structure “multi-actor systems that are not simply complicated, but complex” [5].

The networks can undertake various forms, having a centralized actor or not. Another important characteristic of networks is strength [6]. This feature means that one part of the network can put pressure on other actors. Interdependency and strength together lead to a creation of organism that can evolve in unforeseen ways. Another important dimension of network functioning is the type of relation among actors in the network. An interesting model of analyzing relations between actors in a network has been proposed by R. Keast [7]. Five different ways of institutional relations differ in financing, power, and information linkages. In competition the relations among institutions are rare and, if they are necessary, they are very formalized and contract-based. The second type is cooperation, in which institutions work together in the form of information sharing. Goal is not common but individual aims can only be achieved by data exchange. On the other hand, the third type – coordination implies a centralized body that aligns the work of individual institutions.

As a result, in coordination there is a central actor, who is responsible for dividing resources and duties among institutions. In all three types that is – competition, cooperation and coordination there is no new value created from common work but rather fulfillment of aims that can only be realized through joint work. However, collaboration is different in that by exchanging resources and knowledge something unique is created. This type does not imply a centralized governing body but rather decentralized network structure working on common goals. Finally, consolidation provides for a full merger of institutions into one that can create a new value but at a great initial cost. Therefore, from the network analysis perspective collaboration is the preferred type which can provide full benefits and added value without high investment costs. Besides added value, network structure can also create other benefits such as increased learning, more efficient use of resources, better performance [8,9]. These benefits were likely the motives behind forming a network structure in Polish public healthcare system, yet it is important to mention that actors’ personality and environmental factors i.e. culture are also key to reaping the benefits of network structure [8].

Actors personality should be conductive to leadership and self-direction since centralized decision-taking is often lacking in governance networks. Furthermore, not all cultures feel comfortable with close work-related ties and holistic emphasis required for enhanced network functioning. Another important concept sporadically discussed in the literature is that of effectiveness of networks. Provan and Kenis define network effectiveness “as the attainment of positive network level outcomes that could not normally be achieved by individual organizational participants acting independently” [10]. The effectiveness of network structure is thus connected with collaborative relations within the network that is collaboration should ensure effectiveness of the network structure. An important question to rise is about the meaning of effectiveness in healthcare. Healthcare is a special case of services in which the outcome or output is considered more important than the resources used. These are inputs or costs which are applied to generate an outcome or cure for the patient [11].

Utility – economists measure of happiness – can be construed as satisfaction of the patient derived from the medical procedure. All these aspects such as inputs, outputs and utility can be measured and compared among service delivery processes to gauge if network provided added benefits. In medical field, this if often done to derive cost-effectiveness which is ascertainment of a given outcome at minimal costs. However, cost-effectiveness does not consider utility leading to more painful for patients or prolonged outcomes. The network structure can thus provide a benefit by ensuring that while some actors emphasize cost-effectiveness, others focus more on utility [12,13].

The Current State of the Healthcare System

The current state of the healthcare system is a result of many changes implemented over the last twenty years. The main area of changes has been financing of healthcare with, after the capitalistic reforms, financing of healthcare being a part of responsibilities of the Ministry of Health. At that time, the money from social insurance funds went directly to the budget and the financing was provided to institutions from the budget. After seven years, in 1997, the government insured healthcare fund, was established so that money obtained from social insurance taxes cloud flow to healthcare fund, separately from the budget. This system had functioned until 2003 and had often been criticized due to its decentralized character. Each voivodship had their healthcare fund which managed their funds in an own way. Less developed voivodships had less money to manage which caused strains in the entire system. Therefore, a reform was needed which entered into force in 2004. This reform introduced National Health Fund which had the advantage of decentralized system through voivodship local funds, while also a centralized institution responsible for diving the money among Polish regions.

This system still functions today and although it has been often under fire for not financing needed medical treatments, it is able to allocate scare resources in a cost-effective, but not necessarily the optimal way. The current healthcare system besides the National Health Fund, is responsible for financing medical care from social insurance of residents of Poland, also includes the Ministry of Health and in-patient all day health treatment institutions (hospitals) and out-patient facilities (health clinics). The Ministry of Health is accountable for the system functioning – but not financing – and the other institutions are charged with providing the healthcare services to ill persons. The linkages among the actors are loose in that, in case of referrals it is based on informal knowledge of doctors rather than formal connections. This causes situations when referred patients are being sent away without services being provided, as the doctors referring them cannot formally obliged others to provide the services. This part of the system, therefore, is up for reform by providing formal linkages among particularly hospitals which will require the institutions to take care of referred patients.

Institutional Changes to the Healthcare System

Provision of public services through a network structure in theory can possibly provide variety of benefits. In light of these, the Polish government announced changes to the Polish healthcare system to create a network of hospitals. The Act as of 27 September 2016 introduces structure of network of hospitals with a number of conditions, which must be met, in order for the hospital to be included in the network. The most important conditions include (sec. 2, art. 5 par. 1):

a. optimal number of hospital beds must be provided;

b. ratio of average occupancy rate of hospital beds;

c. type and number of provided healthcare services ensuring complexity and continuity of healthcare, therapy and medical diagnosis in a given specialization;

d. adequate building and equipment conditions appropriate to the scope and type of medical treatment provided;

e. number and qualifications of people providing healthcare treatments in hospitals;

f. maintenance of financial liquidity;

g. a specified level of hospital care;

h. geographical conditions.

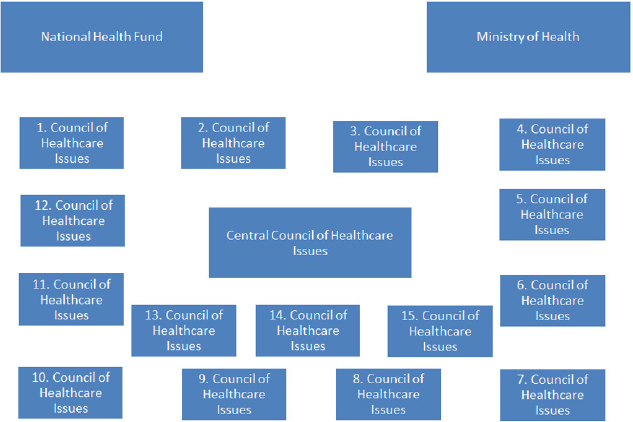

It is noticeable that the following conditions are not precisely set to qualify hospitals to the network structure. More specific directives will be needed to include the hospital in the structure, although the list seems to favour bigger institutions that provide more complex and full treatment in well-equipped facilities in geographical location allowing them to access the highest number of clients. Only the hospitals within the network will be able to obtain financing for providing health treatment. The ones outside with have to reorganize and apply to the network or become private institutions. However, hospitals form only one of the network actors. Polish healthcare system also would include other actors, namely (1) Ministry of Health, (2) Central Council of Healthcare Issues; (3) Regional Councils of Healthcare Issues; (4) National Health Fund. Ministry of Health is the central government institution charged with implementing and coordinating the healthcare policy. National Health Fund is an institution accountable for financing of the healthcare system – on one hand it receives payments from private persons and companies which come from mandatory public health insurance.

On the other hand, it distributes obtained funds to healthcare institutions. The proposed Act introduces two new actors – the Council of Healthcare Issues and Regional Council of Healthcare Issues (sec. 4 of the Proposed Act). The former will coordinate the work of latter and liaise between the Regional Councils and Ministry of Health. The latter will be the key component of the network system as Regional Councils of Healthcare Issues will assess whether the hospitals meet the conditions necessary to include them in the network system and will make 5-year plans on development of healthcare infrastructure in Poland. Each of fifteen voivodships in Poland will have a Regional Council to manage the issues in that part of the country. The centralized part of the healthcare network will be linked to so-called “network of hospitals”. This name has been coined for the proposed Healthcare Act, although the central structure will to a greater extent, be a governance network. At the local level, the healthcare institutions primarily hospitals will be connected forming a kind of policy healthcare network together with Regional Councils of Healthcare Issues.

The benefit of the local healthcare network is to increase the speed of healthcare treatments by increasing the pace of interorganizational decision-taking and referrals. By decreasing the number of institutions and connecting them together the policy maker hopes to make easier and quicker providing combined and complex treatment to patients. On one hand, this aim is viable as decreasing the number of actors in the network and making their more interconnected and interdependent should improve collaboration between them. While on the other hand, by placing some hospitals outside the network structure might make the healthcare services less accessible to people living in villages and smaller cities. In light of the information about the new healthcare network, this governance network will be characterized by uneven distribution of strength and power, although distribution of resources among actors may balance out the network and lead to stable and goal-oriented structure. Firstly, the financial resources will be, as they currently are, assigned to National Health Fund. This should ensure that financial resources are not wasted and spent on ineffective procedures. From the economic point of view, the National Heath Fund does currently serve this purpose but given that healthcare is a special area of human activity were each life is invaluable, the Fund is often veraciously criticized for not approving to fund costly treatments which effects are at best uncertain. Under the new network scheme, another seat of power will be located in the Ministry of Health.

The Ministry will be charged with managing the network via making new regulations and assigning resources to the network actors, other than financial ones. It can be said that these two actors – National Health Fund and Ministry of Health will be engaged in a struggle to most adequately utilize the scare economic resources. The final element of power will be in the hands of fifteen Regional Councils of Healthcare Issues that will make the final decisions on whether a healthcare institution will be a part of the network (Figure 1). An important characteristic of this network is independency among various institutional nodes. Each separate actor is not able to achieve its goals without working together with others. The most crucial interdependency in the network exists between the National Health Fund and Ministry of Health, as one cannot achieve its goals without the other. Whether the relation between them and other actors can be called collaborative will depend on the environmental characteristics of people working in these nodes. It must be said that in healthcare, effectiveness of the network is difficult to achieve. The effectiveness in healthcare results in closer to optimum utilization of resources in order to improve the quality of services provided (quality-effectiveness) or lower the average cost of treatment (cost-effectiveness).

Both are goals of the actors present in public healthcare in Poland. The proposed Healthcare Act stipulated that effectiveness of the hospitals network will be measured in two ways. Firstly, via ratio analysis – profitability ratios, liquidity ratios, performance ratios, and debt ratios that are aimed at measuring financial condition of the hospitals involved in the network. The discussion of these ratios will allow us to understand the requirements set toward the hospitals. Profitability ratios measure the profit generated by the institution, of which most well-known measures include return on assets (net income/average total assets), return on equity (net income/average total equity), net profit margin (net income/total revenue). None of these seem appropriate for a hospital. Firstly, whether hospitals are and should be income generating institutions is an open question. If they are publicly governed, their income comes mostly from National Health Fund and any additional grants or donations and in fact hospitals are limited in their ability to generate income in a traditional sense.

The only possibility for profitability ratios to be applied sensibly is to allow them to provide private and paid care besides the publicly-funded one. This however, can mean that private care giving is maximized and publicly-funded one minimized, if the latter is underfunded. Next, liquidity ratios are focused on assessing the repayment of short-term debts as they mature. The most common ratios – current ratio, acid test (also known as quick ratio), cash ratio – all verify some kind of combination between short-term assets and short-term liabilities. These measures seem more appropriate for hospitals than performance ratios, nonetheless they might not reflect the hospitals real payment capabilities. Hospitals liquidity is usually strained by the payee payment system. If the National Health Fund takes a long-time to pay for medical treatment, then the hospital lacks available funding. Therefore, hospitals have very limited control over liquidity ratios and assessing their management seems inappropriate. Furthermore, performance ratios measure the quality of managerial actions by assessing the turnover of categories such as inventory (sales revenue / inventory), receivables (sales revenue / accounts receivable), short-term liabilities (cost of service provision / accounts payable). In case of hospitals the aim is not to maximize revenues and minimize cost of goods sold as revenues depend (in case of public institutions) on public funds and costs (although should be minimized) based on the number of ill patients.

Only system of long-term illness prevention and healthy lifestyle can minimize the cost of service provision for hospitals, yet these are not part of the focus of hospitals (at least in the proposed Act). Finally, the debt ratios seem more appropriate for hospitals, although not without problems. Debt ratios traditionally measure the debt burden through such methods as debt ratio (total debt/total assets), equity to debt ratio (total equity/total debt) or interest coverage (interest payments / net income). Debt ratios can give insight into how indebted the institution is and if in can pay its interest payments and make capital repayment on time. Yet again although these can tell us a lot about private hospitals debt management, in case of publicly-funded organization this depends upon the funds provided by the National Health Fund and their payment periods. To summarize all these financial ratios seem more appropriate for private institutions then public ones, as in the current public system in Poland most the of financial management is in a way outsourced to another network node that of National Health Funds.

This therefore supports that a premise the provision of healthcare in Poland is performed via a governance network. A significant condition stipulated in the Act is that only those institutions that will maintain high financial standing shall remain in the network. This will force close collaboration with National Health Fund responsible for the financing of actors-institutions as National Health Fund is accountable for optimal allocation of available resources. At the same time, hospitals will have to spend money wisely in order to remain within the hospital network structure and thus obtain national financing. However, the question remains to what degree will publicly-funded institutions be able to provide privately-paid services. If the hospitals will be able to do that, on one hand, the usage of financial ratios will be justified to measure their financial condition, but on the other hand, there is a danger of inadequately provided public health care at the expense of private services. Besides financial measures, the hospitals will also be responsible for maintaining health oriented measures at adequate level. These will be dependent upon morbidity, mortality, comfort of living, and patient satisfaction.

These measures should ensure that hospitals are not only financial oriented but also care about the medical aspects of healthcare. Morbidity is the number of ill patients over a period of time. More ill patients will strain the financial resources of healthcare system, yet a mechanism should be implemented which allows adjustments to financial ratios if the morbidity rate grows. Mortality refers to the number of patients who died. Mortality rate should be differentiated among various institutions as some hospitals, due to the number of illnesses they treat, will have much higher mortality rate than others. Next, comfort of living is a measure dedicated to capturing the conditions at hospitals. This measure should be precisely defined in order to avoid any ambiguities. It can include such things as the size of the room, toilet availability, number of nurses available on a shift, free access to painkilling medication. On the other hand, patient satisfaction is a subjective measure that depends on a great variety of patient and hospital characteristics. Patients’ expectations are different depending on their age, gender, education, place of residence and prior experiences.

Hospitals also differ most importantly in their locale conditions which cannot be changed without much investment. Inclusion of satisfaction measure means that patients should be periodically questioned about their experiences at the medical care facility and such samples of patients must be selected randomly to ensure unbiased results. Unfortunately, neither precise financial ratios nor health ratios are known for the enforced Act. These are up to be decided and clarified by the Ministry of Health. The recommendation should be for the Ministry of Health to delineate such level of ratios to ensure that citizens of poland present within the healthcare network receive needed medical treatment to be provided to all residents of Poland. Additionally, they should be high enough to ensure financing is not wasted and actors are motivated to use them in a most effective way. Needless to say, these measures stipulated in a proposed Act, focus on cost-effectiveness and financial stability of hospitals but to a lesser extent on qualityeffectiveness. Other three measures included in the proposed Act (art. 31) are process-oriented and focus on governance network delivery.

Firstly, relations between medical personnel and patients as concerns, diagnostic procedures and treatments. This is very difficult to measure but governance network theory can provide insight on how to measure such ambiguities. To do this, governance network mapping is necessary in order to draw up interrelations between all actors in a network. This will allow for an understanding of connections, both formal and informal in nature, which can lead to pointing the weaknesses and strongholds in the medical care delivery process. Analyzing the network structure will also allow for risk assessment of, the second measure stipulated by the Act, namely the risk of complications of the performed treatments. By calculating the probability of certain unintended results of treatment, governance network does provide possibility to assess the risk. Third measure listed in the proposed Act is the level of existence of in-hospital infections. This is one of the risks that can occur while providing medical treatment to in-house patients.

The reformed system by providing linkages among institutions will quicken the healthcare treatment being provided to patients. Situations of sending patients away without services being provided should not take place as both institutions – referring one and the one to which patient is being referred – will be held accountable for taking care of the patient. What is surprising is that out-patient healthcare clinics seem not to be part of the system of linkages. This is an unquestionable weakness of the suggested reform as patients will be prone to being sent away and wait until they find themselves in a network of hospitals. Another drawback worth mentioning is the composition of Regional Councils of Healthcare Issues. According to art. 18 of the proposed Act, they will be composed of thirteen persons namely:

a. two persons delegated by the Ministry of Health,

b. one person delegated by the Ministry of Defense,

c. one person delegated by the Ministry of Interior,

d. two persons delegated by the Association of Polish Counties,

e. two persons delegated by the Union of the Provinces of the Republic of Poland,

f. two persons delegated by the Association of Rectors of Medical Universities,

g. one person delegated by the appropriate governor of the voivodship,

h. two persons delegated by the regional National Health Fund.

It can be seen that financial authorities are not represented here, which not only is surprising given that financial measures are emphasized as important to overall governance network functioning, but also that other areas of government are represented which does not seem to be very significant in light of the system framework and the measures suggested. Moreover, the Act provides only one way in which results will be monitored. This is the by Monitoring the Centre and a delegated to the particular institution monitoring person (sec. 7 of the Act). In each period a sample consisting of 10% of institutions included in the network of hospitals will be monitored. There is no specific education, except for being a higher-education diploma holder, required of the monitoring person. This may not be adequate as, at this moment, without specific objective measures the outcome of such monitoring maybe subjective and biased. In particular, this bias might be towards institutions which either cannot maintain good financial conditions but are characterized by high quality medical treatments or which have good financial standing but need to improve their medical services. What balance needs to be attained by measures for the hospitals to remain in the network of hospitals is yet to be seen. Being thrown out of the network of hospitals is an act that will leave the institution without any public financing. This is quite controversial as most healthcare professionals are worried that this will lead to decreasing employment among medical personnel and privatizing public institutions. While it may not happen at all, it may also not be a negative phenomena for medical profession because institutions inadequate from cost-effectiveness and quality-effectiveness perspective should not be financed with public money. Overall, the public financing should be wisely spent and the network of hospitals should ensure that.

Conclusion

The article presents the proposed changes to publicly-financed medical care services in Poland and sets this in light of the currently existing framework. After the proposed modifications, the system will be organized as a governance network with a number of interdependent actors. The changes once implemented should be beneficial to the patients as increased collaboration among actors is expected. The focus on cost-effectiveness of the new system is a result of the current financial strain. Many measures have been proposed to monitor the system including financial ratios of profitability, liquidity, performance, and debt, alongside medical treatment measures namely morbidity, mortality, comfort of living, and patient satisfaction. The latter ones are quality-oriented used to monitor the performance aspects of the network with measures such as patient-doctor relations and risk of complications and risk of in-hospital infections. Although using these should benefit hospitals and patients alike, nonetheless the lack of specificity and dynamic between them is worrisome and should be addressed by decision-makers. Without empirical testing it is difficult to assess whether the system will in fact benefit actors of the governance network but in theory it seems the structure will be beneficial as it will promote both cost- and quality-effectiveness.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

No funding for this work has been received. No research grants or company sponsorship has been received for this work. I confirm that I have read BioMed Central’s guidance on competing interests and none of the authors have any competing interests.

References

- (2017) Eurostat Statistics Explained, Healthcare Expenditure Statistics.

- Kickert WJM, EH Klijn, JFM Koppenjan, Rhodes (1997) RAW Foreword. In: Managing Complex Networks. Strategies for the Public Sector. editors. Sage Publications, London.

- (2012) Torfing Jacob Governance Networks. The Oxford Handbook of Governance 1.

- KI Hanf, FW Scharpf (1978) Scharpf FW: Interorganizational policy studies: Issues, concepts and perspectives. In: Interorganizational Policy Making SAGE, London, England. pp. 345-370.

- Kicker WJM, Klijn EH, Koppenjan JFM (1997) Introduction: A Management Perspective on Policy Networks. In: Managing Complex Networks. Strategies for the Public Sector. Sage Publications, London. p. 1-2.

- Emerson, Richard M (1962) Power-Dependence Relations. American Sociological Review 27(1): 31-41.

- Keast, Robyn (2015) A Guide to Collaborative Practice: Informing Performance Assessment & Enhancement.

- Brass Daniel J, Joseph Galaskiewicz, Henrich R Grave, Wenpin Tsai (2004) Taking stock of networks and organizations: A multilevel perspective. Academy of Management Journal 47: 795-817.

- Huxham, Chris, Vangen, Siv (2005) Managing to Collaborate. Routledge, London.

- Provan, Keith G, Kenis, Patrick (2008) Modes of Network Governance: Structure, Management, and Effectiveness. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 18(2): 229-252.

- Brent Robert J (2014) Cost-Benefit Analysis and Health Care Evaluations, Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, UK.

- Klijn EH, Koppenjan JFM (2014) Complexity in Governance Network Theory. Complexity, Governance & Networks. p. 61-70.

- (2016) Proposed Act of 27 September 2016 on Network of Hospitals.

Mini Review

Mini Review