Abstract

We report a case of infective endocarditis (IE), in which an intracranial mycotic aneurysm (ICMA) was detected. Meanwhile, a concomitant herpes simplex encephalitis (HSE) was suspected, to our knowledge, which has not been documented in previous literature and challenges us to rethink about the etiologies of meningoencephalitis and encephalopathy in IE patients.

Keywords: Infective Endocarditis; Staphylococcus Intermedius; Intracranial Mycotic Aneurysm; Meningoencephalitis; Herpes Simplex Encephalitis

Abbreviations: IE: Infective Endocarditis; ICMA: Intracranial Mycotic Aneurysm; HSE: Herpes Simplex Encephalitis; CSF: Cerebrospinal Fluid; DSA: Digital Subtraction Angiography; MCA: Middle Cerebral Artery; ECG: Electrocardiogram; TTE: Transthoracic Echocardiography; aEEG: Ambulatory Electroencephalogram; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; ICU: Intensive Care Unit

Introduction

A 49-year-old married male was admitted to neurology

department with a sudden loss of consciousness and convulsing

lasting for about 1 minute. It occurred just when he was waiting for

an interview in the outpatient clinic complaining of repeated fever

(up to 38.5℃) accompanying with mild-to-moderate headache for

3 days, during which he was administered with “cephalosporin

antibiotics” intravenously once a day. His fever and headache

got alleviated, but there were several episodes of speech arrest

with drooling for seconds. Two weeks prior, he had had flu-like

symptoms, including fatigue, loss of appetite and cough. He was

generally well without addiction of alcohol, tobacco or drugs. He

had been keeping a pet dog for years. On admission, he was afebrile

with other normal vital signs. On physical examinations, there was

nothing abnormal but declined responsiveness and neck stiffness.

The brain computerized tomography (CT) scan right after the onset

of his abrupt convulsion detected no abnormality.

Lumber puncture was performed expeditiously after admission.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was slightly turbid and of a very pale

pink even in 3 tubes, while CSF analysis revealed no red cells but

elevated white cell counts (100 cells/ μL) with 96% of mononuclear

cells, with normal glucose and chloride concentration, and normal

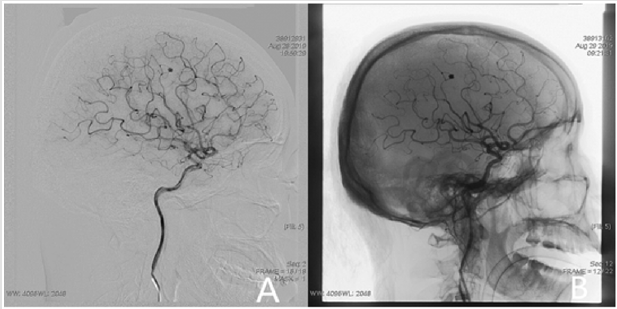

protein levels. A subsequent Digital Subtraction Angiography (DSA)

discovered a berry-like aneurysm (Figure 1), located on the distal

branch of right middle cerebral artery (MCA). On the second day

of admission, no significant inflammatory activity was noticed

on laboratory testing. We performed an endovascular coiling treatment to the intracranial aneurysm under general anesthesia

(Figure 1). In the next three days, on electrocardiogram (ECG)

monitor displayed paroxysmal bradycardia (48 to 60 beats/min)

frequently with hemodynamic stability. But the patient complained

no palpitation or any symptoms of heart failure. No valve murmurs

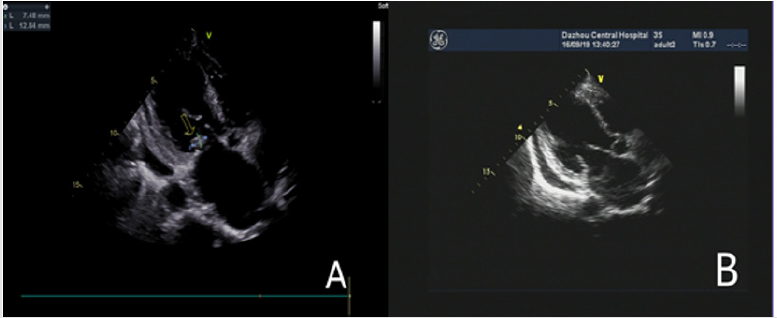

were detected, neither. On hospital day 5, aiming to determine the

underlying condition of bradycardia, we performed transthoracic

echocardiography (TTE) and observed a lengthened anterior leaflet

of matrial valve, a valve vegetation (2.5 mm × 12.8 mm) on the

posterior leaflet of mitral valve, and moderate regurgitation (Figure

2). Infective endocarditis (IE) was highly suspected.

Figure 1:

A. Intracranial aneurysm on right MCA detected by DSA.

B. Endovascular coiling treatment to the intracranial aneurysm under general anesthesia.

Figure 2:

A. Mitral valve vegetation observed by TTE.

B. Diminished vegetation after two weeks antibiotics treatment with still lengthened anterior leaflet of matrial valve.

An empirical antimicrobial therapy was set up with ceftizoxime sodium (2000mg every 12 hours, i.v) before blood sampling. Later in 3 to 4 days, Staphylococcus intermedius and Staphylococcus caprae were identified by blood culture (Bact/AlERT 3D with Mycobacteria indication; bioMérieux) in aerobic and anaerobic bottles, respectively. Antibiotics sensitivity testing (VITEK 2 AST-GP67 Test kit; bioMérieux) revealed that the isolates was susceptible to oxacillin, vancomycin, cefazolin and levofloxacin, etc. Then the patient was treated with levofloxacin (600 mg/day, i.v) combined with ceftizoxime sodium for a total of two weeks, during which another 2 bottles of blood culture turned out sterile, while a mitral murmur developed still without any signs of heart failure. At the end of the antibiotic course, TTE revealed no vegetation, but more severe regurgitation (Figure 2). The patient was then transferred to Chongqing Xinqiao hospital for further management, where another TTE performed one week apart from the second one in our hospital, demonstrated a bicuspid chordae tendinae rupture on the posterior leaflet coupled with mitral prolapse and remarkable regurgitation.

After a well coiled intracranial aneurysm was ensured by CT angiography, the patient underwent a mitral valve repair surgery with an annuloplasty ring. On the other hand, as the provisional diagnosis of intracranial infection on admission, we performed a routine serologic testing for viral antibodies which showed serumpositive HSV1-2 IgM (1.39, normal values: 0~1.1). Since admission, the patient had not had a fever, and the headache resolved overtime. Yet, he developed a mild altered mental status with agitation and personality change. His wife reported an absencelike seizure for seconds during a episode of bradycardia. However, the followed ambulatory electroencephalogram (aEEG) didn’t observed abnormalities. Unfortunately, we failed to convince him to take another lumber puncture and cerebral magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanning. But, neurologically, a concomitant herpes simplex encephalitis (HSE) could not be ruled out. In the 6 months follow-up, the patient has been getting recovered.

Discussion

Infective endocarditis (IE) is a life-threatening infectious

disease with a high in-hospital mortality of 15% to 22%

[1]. Worldwide, streptococci and staphylococci are the main

pathogenic organisms, represented by Streptococcus pneumoniae

and Staphylococcus aureus [2], respectively. In this case, two

organisms were recovered in aerobic and anaerobic media from

one set blood sample, which may be due to contamination of

specimen and less likely the causative agent. But as observed

by TTE, the diminished valvular vegetation was a proof of active

endocarditis and a lengthened anterior leaflet of matrial valve

may be suggestive of preexisting valve pathological change. With

the major criterion and the predisposition, taking account of fever

and a high likelihood of intracranial mycotic aneurysm (berrylike

protrusion on distal MCA), we believe that this is a definite IE

which meets the modified Duke criteria [2]. About 20% to 55% of

IE patients suffer from neurological complications [2,3], which can

be generally categorized into six types: cerebral ischemic stroke,

intracranial hemorrhage, meningitis or meningoencephalitis, brain

abscess, toxic encephalopathy, and intracranial mycotic aneurysm

(ICMA). In our case, the clinical presentations were characterized

by fever, headache, seizures, mental disorders and neck stiffness,

and Lumber puncture showed pink CSF with mild pleocytosis and

negative CSF culture.

A subtle blood leak from a ruptured ICMA can fully explain

the symptoms and the CSF profile of meningeal reaction. But

seizures and mental disorders are not quite common in such

condition, and in terms of differential diagnosis, two entities must

be taken into consideration. First, in active IE, the intracranial

metastasis of bacteria from cardiac valve could cause meningitis

or meningoencephalitis, with or without positive CSF culture.

Due to the significant impact of stroke on prognosis of IE, and the

side effects of intracranial hemorrhage caused by anticoagulant

therapy after cardiac surgery, there are numerous studies that

focus on stroke and the timing of cardiac surgery in IE patients,

while there are few studies elaborating on all types of neurological

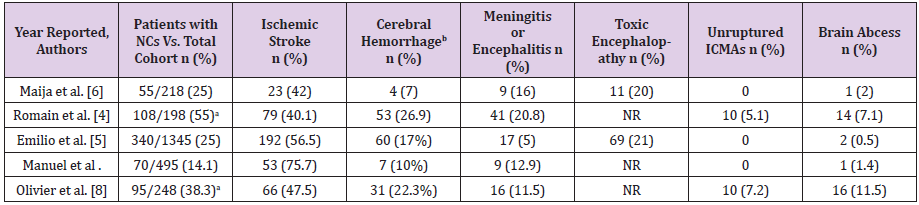

complications in IE. In this regard, five large cohorts studies [4-8]

demonstrated the high incidence of meningitis and encephalopathy

in IE, just behind ischemic stroke or cerebral hemorrhage (Table

1). Second, with the sero-positive HSV1-2 IgM in this case, we

suspected a concomitant herpes simplex encephalitis (HSE) which

can manifest as meningitis, as well as encephalopathy. Of patients

with HSE, around 50% have seizures [9] and most patients present

with neuropsychological and psychiatric impairment [10].

Table 1: Neurological complications ( NCs ) in IE patients from five large cohorts studies.

ICMAs, intracranial mycotic aneurysms; NR, Not reported.

aSome patients in the two studies suffered more than one episode of NCs.

bCerebral Hemorrhage included SAH due to ruptured ICMAs.

HSE may even cause arrhythmia such as bradycardia and ictal asystole [11]. The CSF analysis may be normal or haemorrhagic in minority of HSE patients [12]. And it is not uncommon that HSE is sometimes an auto limiting infection. What’s more, IE is the major cause of ICMA, while ICMA is just a rare neurological complication of IE (only in 2% to 10% of cases ) and can be secondary to virus infection [13]. As HSV can induce arteritis in brain, HSV may play a role in the genesis of aneurysms, which has been discussed in few articles [14,15] but has never been confirmed up to now. Universally, the confirmation of etiologies of infections in central nervous system (CNS) relies on CSF culture, specific antibodies testing or more preferable polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in CSF samples. However, in two of the five large cohorts as mentioned above [4,5], of the episodes identified as meningitis or meningoencephalitis in IE, only 39% (16/41) and 13% (2/15) were confirmed by positive CSF culture. And only in Romain Sonneville’s paper [4], the CSF profiles were provided and revealed moderate elevated CSF cell counts (222 cells/μL [32-600 cells/μL]]) and protein levels (0.9 g/L [0.63-1.57 g/L]), which is a viral infection-like CSF profile.

Moreover, in Emilio García-Cabrera’s survey [5], there were 69 episodes designated as toxic encephalopathy, which is a diagnosis of exclusion and defined as mental status change with normal CSF analysis and without abnormal cerebral CT findings. Taking all together, from a perspective of neurology, these studies fall short of the true causes for the meningoencephalitis and encephalopathy in IE. Although in the present case, HSE was far away from an confirmed condition for lack of CSF HSV-specific antibody and PCR, it suggested a possibility that IE may be accompanied with HSE and HSV may be the etiology of meningoencephalitis and encephalopathy in IE patients, especially for those in intensive care unit (ICU), since Bruynseels et al. [16] have found a high load HSV in the throat of ICU patients and Lukas Schuierer et al. [17] confirmed that HSV can be reactivated in ventilated patients. In summary, we report a case of infective endocarditis. It was left- sided with native mitral valve involvement and caused a large vegetation (>10mm). It was accompanied with an intracranial mycotic aneurysm and complicated by a suspected herpse simplex encephalitis, which reminds us that ongoing vigilance should be kept not only for IE complications but also for comorbities of IE, and the etiologies of meningoencephalitis and encephalopathy in IE patients must be cautiously monitored.

References

- Murdoch DR, Corey GR, Hoen B, Miró JM, Fowler VG, et al. (2009) Clinical presentation, etiology, and outcome of infective endocarditis in the 21st century: The International Collaboration on Endocarditis-Prospective Cohort Study. Arch Intern Med169(5):463-473.

- Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, Fowler VG, Tleyjeh IM, et al. (2015) Infective Endocarditis in Adults: Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Therapy, and Management of Complications: A Scientific Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association. Circulation132(15):1435-1486.

- GálvezAcebal J, RodríguezBaño J, MartínezMarcos FJ, Reguera JM, Plata A, et al. (2010) Prognostic factors in left-sided endocarditis: results from the Andalusian multicenter cohort. BMC Infect Dis10:17.

- Sonneville R, Mirabel M, Hajage D, Tubach F, Vignon P, et al. (2011) Neurologic complications and outcomes of infective endocarditis in critically ill patients: the ENDOcardite en REAnimation prospective multicenter study. Crit Care Med39(6):1474-1481.

- GarcíaCabrera E, FernándezHidalgo N, Almirante B, IvanovaGeorgieva R,Noureddine M, et al. (2013) Neurological complications of infective endocarditis: risk factors, outcome, and impact of cardiac surgery: a multicenter observational study. Circulation127(23):2272-2284.

- Heiro M, Nikoskelainen J, Engblom E, Kotilainen E, Marttila R, et al. (2000) Neurologic manifestations of infective endocarditis: a 17-year experience in a teaching hospital in Finland. Arch Intern Med160(18):2781-2787.

- Wilbring M, Irmscher L, Alexiou K, Matschke K, Tugtekin SM (2014) The impact of preoperative neurological events in patients suffering from native infective valve endocarditis. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg18(6):740-747.

- Leroy O, Georges H, Devos P, Bitton S, De Sa N, et al. (2015) Infective endocarditis requiring ICU admission: epidemiology and prognosis. Ann Intensive Care5(1):45.

- Misra UK, Tan CT, Kalita J (2008) Viral encephalitis and epilepsy. EpilepsiaSuppl 6:13-8.

- Harris L, Griem J, Gummery A, Marsh L, Defres S, et al. (2020) Neuropsychological and psychiatric outcomes in encephalitis: A multi-Centre Case-Control Study. PLoS One15(3):e0230436.

- Gooch R (2009) Ictal asystole secondary to suspected herpes simplex encephalitis: a case report. Cases J2:9378.

- Tunkel AR, Glaser CA, Bloch KC, Sejvar JJ, Marra CM, et al. (2008) The management of encephalitis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis47(3):303-327.

- Wilson WR, Bower TC, Creager MA, AminHanjani S, O'Gara PT, et al. (2016) Vascular Graft Infections, Mycotic Aneurysms, and Endovascular Infections: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation134(20):e412-e460.

- Nunes ML, Pinho AP, Sfoggia A (2001) Cerebral aneurysmal dilatation in an infant with perinatally acquired HIV infection and HSV encephalitis. Arq Neuropsiquiatr59(1):116-118.

- Annunziato PW, Gershon A (1996) Herpes simplex virus infection. Pediatric in Review 17:415-425.

- Bruynseels P, Jorens PG, Demey HE, Goossens H, Pattyn SR, et al. (2003) Herpes simplex virus in the respiratory tract of critical care patients: a prospective study. Lancet362(9395):1536-1541.

- Schuierer L, Gebhard M, Ruf HG, Jaschinski U, Berghaus TM, et al. (2020) Impact of acyclovir use on survival of patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia and high load herpes simplex virus replication. Crit Care24(1):12.

Case Report

Case Report