Abstract

Cancer of the hypopharynx and larynx, in spite of advancements in chemoradiotherapy, remains a deadly disease, particularly in developing nations. This is often attributed to it being detected late in the disease progression; and while neoadjuvant chemotherapy has worked wonders in the early stages of the disease, advanced manifestations often warrant more radical surgical resection. Following a resection adequate reconstruction is required, not only to fill a defect, but also with the aim of restoring some degree of functionality to the patient’s speech and swallowing. Plastic surgeons specializing in head and neck reconstruction have utilized a wide variety of microvascular procedures to deal with laryngopharyngeal reconstruction. The main stay of treatment is the use of a range of local pedicle flaps, or free flaps from elsewhere in the body to cover the defects. Throughout this paper, the various flap choices are compared and reviewed. While it appears, there is no unequivocal superiority of one type of flap over the other, this is dependent on a number of factors. Often the outcome and choice of flap is influenced by the size of defect, prior radiotherapy, surgeon’s familiarity with the technique, patient’s preoperative morbidity, and the need to restore function.

Keywords: Laryngopharyngeal; Pharyngeal; Laryngeal; Cancer; Reconstruction; Flap

Abbreviations: ALT: Anterolateral Thigh Flap; LDMC: Latissimus Dorsi Myocutaneous Flap; PMMC: Pectoralis Major Myocutaneous Flap; RFFF: Radial Forearm Free Flap; SCM: Sternocleidomastoid; TDAP: Thoracodorsal Artery Perforator; TPFF: Temporoparietal Free Flap

Short Communication

Cancer of the hypopharynx and larynx remains a deadly disease, often owing to diagnosis late in its progression. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy has superseded the more aggressive options of primary extensive resection, although, a small portion of cases, especially those that recur, present a therapeutic challenge. Salvage total laryngectomy or laryngopharyngectomy are the operations of choice. Broadly, reconstruction of the hypopharynx and larynx can be categorized based on the following requirements: cover of a partial or circumferential defect, restoration of swallowing and/or speech, patient co-morbidities, previous radiotherapy to the recipient site, and the indication for flap as a result of trauma, or tumour resection [1]. The ideal reconstruction involves recreation of a digestive conduit with vascularized tissue that enables early restoration of swallowing and speech while minimizing complications such as fistula, stricture, anastomotic site leakage, or flap necrosis. Single stage reconstructions are preferred for minimal morbidity and mortality. The two common options used for reconstruction are pedicled or free flaps.

For reconstruction of the pharynx, the options for pedicled flaps include pectoralis major myocutaneous flap (PMMC), latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap (LDMC), sternocleidomastoid, trapezius, submental, thoracodorsal artery perforator (TDAP), and supraclavicular artery flaps. Free flap options can be divided into two groups: fasciocutaneous flaps - anterolateral thigh flap (ALT) or radial forearm free flap (RFFF), and visceral flaps - gastroomental or jejunal free flap. With regards to reconstruction of the larynx, similar options are considered, with inclusion of the temporoparietal free flap (TPFF). Whilst these operations can maintain a reasonable degree of functionality and improved oral intake, both are often beset with the complications mentioned above, often deterring many a good reconstructive microsurgeon. The choice of flap is influenced by whether the defect is created following primary surgery or is a salvage procedure performed for recurrent disease following radiotherapy. In addition, reconstruction of a cartilaginous structure is often fraught with failure due to its non-vascularized nature and often requires augmentation with a vascularized carrier : this may need to be performed in two stages [2]. The goal of this paper is to critically review the pros and cons of the various techniques for laryngopharyngeal reconstruction based on current available evidence.

Pedicled Flaps

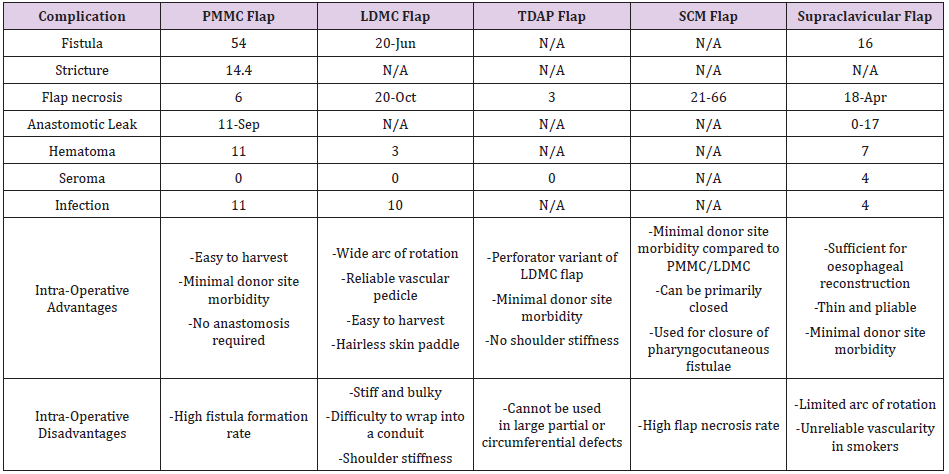

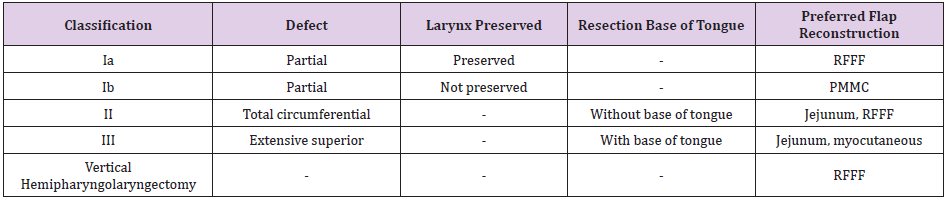

It is useful to analyse the options of pedicled flaps by subcategorizing them into surgeries that only require coverage of a partial defect vs. a circumferential defect and comparing each option in terms of usefulness, technical challenges and complication rates. Smaller or partial defects often engage the use of the submental flap: this is a thin flap with low donor site morbidity that is easy to raise and is associated with minimal complications. However, it cannot be used for circumferential defects [3]. Larger partial defects are afforded a wide choice of pedicle flaps: supraclavicular artery flap, thoracodorsal artery flap (TDAP) and/or the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) flap. Circumferential or more extensive defects may require use of the latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap (LDMC) or the pectoralis major myocutaneous flap (PMMC) among pedicled flaps. A short summary of the percentages of complications and advantages of these flaps pooled from the results of various studies is available below (the use of N/A refers to data not being reported by the individual study) (Table 1). A further classification of the type of defect was put forth by van der Putten et al. [4] wherein they suggested a defect-oriented approach to choosing the type of flap : this is summarised in the table below (Table 2).

Free Flaps

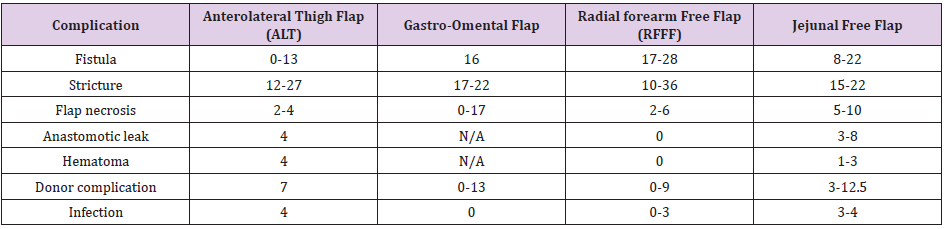

Free flaps are currently the gold standard for microsurgical reconstruction, and therefore remain the other primary option to choose when the question of laryngopharyngeal reconstruction is required. For this purpose, they can be categorized into myocutaneous flaps or visceral flaps. The most common myocutaneous free flaps used are the anterolateral thigh flap (ALT) or the radial forearm free flap (RFFF), while the common visceral flaps used include the jejunal free flap and the gastro-omental flap [1,2]. Compared to pedicled flaps, free flaps offer superior restoration of swallowing and speech function, which is consistently seen across multiple studies. The compared percentages are shown below (Table 3).

The oldest among the free flap techniques was the jejunal free flap, and while it logically should seem the ideal conduit to replace the upper esophagus/hypopharynx, it is associated with greater morbidity to the donor site and need to monitor the flap via an externalization of bowel. It is agreed among current proponents that the primary choice among non-visceral free flaps is the ALT flap. The advantages of this flap are many and there is good functional restoration of speech and swallowing with a consistent pedicle. The only significant contraindication apart from heavily compromised peripheral vascular disease is obesity, and the radial forearm free flap (RFFF) provides a suitable alternative in this situation.

Discussion

The choice of flap, as stated earlier, is dictated by various considerations. No one flap has proven superiority over the other [5]. Whilst pedicled flaps provide the benefit of coverage of large defects with shorter operative times and lower intra- and postoperative complications, these flaps have a limited arc of rotation and are associated with higher donor site morbidity and poor cosmesis compared to free flaps. Free flaps are the current standard for microsurgical reconstruction: the fasciocutaneous flaps are often used for circumferential defects with a linear suture line and visceral free flaps are considered where total reconstruction of the esophagus is required. Free flaps are useful in the recipient site post-radiotherapy, but are associated with higher intra-operative times and, in some patients, higher risk of ischemia and necrosis [6]. There is no clear choice for the optimal flap for laryngotracheal reconstruction. Review articles summarize their results based on pooled effects of retrospective studies with little statistical significance.

However, from individual data of single center experience with more commonly used flaps, it would seem that for smaller partial defects it is not unreasonable to consider a pedicled locoregional flap: this involves shorter operative time, minimal donor site morbidity and reduced rates of complications in a patient with no co-morbidities. Ki et al. [1] in 2015 summarized various options for laryngotracheal reconstruction, however, this article does not comment on the patient sample size, statistical significance of reported outcomes or equipoise of patient characteristics. Welkoborsky et al. [7] compared free flaps versus pedicled flaps for reconstruction of large pharyngeal defects. The conclusion of the authors was that ALT flap and jejunal free flaps are the first flap of choice for these defects, with the PMMC flap providing an excellent alternative as a second-line option and in cases where previous chemoradiotherapy has been used at the recipient site. A fine balance has often to be made with respect to the patient’s current clinical condition and prognosis versus cosmesis and restoration of speech and swallowing. Often it is a situation of one outweighing the other that guides the surgeon in choosing the appropriate flap. It is difficult therefore to interpret these results: the studies are not case control matched, and the reasons put forth for differing complication rates is sometimes not clear. What is clear, however, is that familiarity with a technique with good pre-operative condition and reliable vascularity provides better outcomes.

Conclusion

In summary, there are various options for laryngopharyngeal reconstruction. The choice of flap is determined by multiple factors; the size and type of defect and the surgeon’s familiarity remain the primary factors influencing the choice of flap. There is no demonstrated superiority of one type of flap over the other with respect to partial defects. In circumferential or larger defects, ALT and jejunal free flaps offer better speech and swallowing function with reduced donor site morbidity compared to other pedicled and/or free flaps. However, in the presence of previous donor site radiotherapy, the pedicled pectoralis flap (PMMC) has superior outcomes with respect to stricture and fistula formation compared to free flaps. The advent of robotic transoral microsurgery offers future direction in this field, and larger sample sizes with wellbalanced prospective studies and/or randomized trials would provide more robust evidence in determining the ideal method of reconstruction.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ki S, Choi J, Sim S (2015) Reconstructive Trends in Post-Ablation Patients with Esophagus and Hypopharynx Defect. Arch craniofacial Surg 16(3): 105-113.

- Gilbert R, Neligan P (2005) Microsurgical laryngotracheal reconstruction. Clin Plast Surg 32(3): 293-301.

- Nagel T, Hayden R (2014) Advantages and limitations of free and pedicled flaps in reconstruction of pharyngoesophageal defects. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 22(5): 407-413.

- Van der Putten L, Spasiano R, De Bree R, Bertino G, Leemans C, et al. (2012) Flap reconstruction of the hypopharynx: a defect orientated approach. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 32(5): 288-296.

- Haidar YM, Kuan EC, Verma SP, Goddard JA, Armstrong WB, et al. (2019) Free Flap Versus Pedicled Flap Reconstruction of Laryngopharyngeal Defects: A 10-Year National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Analysis. Laryngoscope 129(1): 105-112.

- Chen W, Chang K, Chen C, Shyu V, Kao H (2013) Outcomes of anterolateral thigh flap reconstruction for salvage laryngopharyngectomy for hypopharyngeal cancer after concurrent chemoradiotherapy. PLoS One 8(1): e53985.

- Welkoborsky H, Deichmuller C, Bauer L, Hinni M (2013) Reconstruction of large pharyngeal defects with microvascular free flaps and myocutaneous pedicled flaps. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 21(4): 318-327.

Short Communication

Short Communication