Abstract

Background: Infection by hepatitis C virus (HCV) is the leading cause of chronic liver disease worldwide, the patients unaware of their infection and at risk for developing cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. At least six major HCV genotypes comprising numerous, more closely related subtypes have been identified.

Objective: The aim of this study was to study the seroprevalence and epidemiology of the HCV genotypes in hemodialysis and healthy blood donors in Khartoum - Sudan.Methods: A total of 1203 serum samples were collected from individuals attending out-patients’ units at Khartoum State. The study population comprises two groups. Blood donors study groups (n= 600) and chronic hepatic patients during the course of HCV infection (n= 603). Serum samples was screened using enzyme linked immunesorbent assay (ELISA) (Biokit, A.S. Spain®). Positive samples (n=100) were identified for genotypes and epidemiological study by HCV Real-TM genotype SC (Sacace Biotechnologies Italy) and questionnaire.

Results: Out of 600 blood donors 8 (1.3%) were found to be positive for HCV antibodies, while the hemodialysis patient (603) showed higher seroprevalence of HCV (15.2%).100 HCV seropositive samples were subjected to genotyping and analysis of epidemiological effect using RT- PCR, HCV genotype 4 was identified the predominant genotype (92%) followed by genotype 2 (4%), Genotype 1 (2%) and 3 (2%) in different groups.

Keywords: Calves; Ectoparasite; Ethiopia; GIT helminthes; Infestation; Risk Factors

Abbreviations: HCV: Hepatitis C Virus; ELISA: Enzyme Linked Immune-Sorbent Assay; HBV: Hepatitis B Virus; PCR: Polymerase Chain Reaction; RT-PCR: Real Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) was identified in 1989 and was found to be responsible for 70- 90% of post-transfusion hepatitis in all countries where blood was tested for Hepatitis B virus (HBV) markers [1]. Humans seem to be the sole source of infection and inoculation with blood and blood products is the most recognized mode of transmission [2]. HCV RNA can be detected one or two weeks after infection and anti-HCV antibodies are usually positive six weeks from infection [3]. The lack of convenient culture system for HCV implies the use of molecular biology to assess viremia, Amplification of viral nucleic acid by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), provides a highly sensitive and antigen-antibodyindependent method to detect ongoing viral infection. Knowledge of genotype is important for planning of treatment regimes, whereas subtype identification is useful in epidemiological studies and outbreak investigation. We describe HCV genotyping and subtyping assays, based on real-time PCR, that is sensitive, specific, and reliable [4-6]. Total six major HCV genotypes and multiple subtypes have been identified from around the world [7].

Identification of HCV genotype /subtype is extremely important clinically before prescribing therapy because genotypes 1 & 4 show more resistance as compared to genotypes 2 and 3 to PEG-IFN plus ribavirin therapy, therefore different types of HCV genotypes require different duration and dose of anti-viral therapy [8]. HCV genotypes display significant differences in their global distribution and prevalence, so genotyping a useful method for determining the source of HCV transmission as well as clinical pictures of an infected localized population [9]. HCV RNA can be detected one or two weeks after infection and anti-HCV antibodies are usually positive six weeks from infection [3]. The complexity and uncertainty related to the geographic distribution of HCV infection and chronic hepatitis C, determination of its associated risk factors, and evaluation of cofactors that accelerate its progression, underscore the difficulties in global prevention and control of HCV. Because there is no vaccine and no post-exposure prophylaxis for HCV, the focus of primary prevention efforts should be safer blood supply in the developing world, and safe injection practices in health centers [10]. Therefore, the study will be more reliable to determine frequencies and Epidemiology of HCV genotypes in hepatic patients in Khartoum state.

Materials and Methods

This is descriptive cross-sectional study that was conducted, to determine the frequencies and epidemiology of HCV genotypes in hepatic patients in Khartoum state - Sudan by ELISA (third generation) using recombinant HCV - antigens were purchased from Biokit, A.S. Spain, as well as real time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) in positive individuals among Sudanese hepatitis patients in Khartoum state using QIAamp Viral RNA Kit were purchased from QIAGEN. A total of 1203 randomized individuals at different medical centers were collected and screened for HCV with specifically designed data sheets from patients by using third generation of ELISA kits, and then hundred positive patients with hepatitis C virus infection were selected for further molecular studies. Informed consent was taken in written form from each participated patient including, demographic characteristic, age, district, and estimated time of infection along with complete address and phone number of the patients. Written informed consent was taken from each patient.

Extraction of Nucleic Acid

QIAamp Viral RNA Kit provides the fastest and easiest way to purify viral RNA for reliable use in amplification technologies. Viral RNA can be purified from plasma, serum and body fluid free cell. Samples may be fresh or frozen, but if frozen, should not be thawed more than once. The extraction kit of viral RNA was purchased from QIAGEN and supplied as follows.

HCV Qualitative Test

Samples were subjected firstly for the detection of HCV RNA qualitatively as previously describe by Idrees [11]. Reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) was done for the identification of HCV RNA. RNA was extracted from 100 μl patient’s sera using Qiagen RNA extraction kit according to the kit protocol. RT.PCR were performed using Taq DNA polymerase enzyme (Fermentas Technologies USA) in a volume of 20 μl reaction mix.

HCV Quantitative Test

HCV RNA quantification was done by using Smart Cycler II Real-time PCR (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, Calif. USA) with HCV RNA quantification kits (Sacace Biotechnologies, Italy). The Smart Cycler II system is a PCR system by which amplification and diagnosis were accomplished at same time with TaqMan technology (Applied Biosystems 7500) using fluorescent probes to investigate amplification after each replicating cycle. The data were analyses through fluorescence curves with the software of Real Time PCR instruments on the 2 channels (FAM/Green and Joe/Yellow/HEX/ Cy3).

HCV Genotyping

Extraction of nucleic acid QIAamp Viral RNA Kit provides the fastest and easiest way to purify viral RNA for reliable use in amplification technologies. Viral RNA can be purified from plasma, serum and body fluid free cell. Samples may be fresh or frozen, but if frozen, should not be thawed more than once. The extraction kits of viral RNA were purchased from QIAGEN. All qualitative PCR positive sera were subjected to HCV genotyping by using type-specific HCV genotyping procedure as described previously in detail [12]. Briefly, 10 μl (about 50 ng) of HCV RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using 100 U of M-MLV RTEs at temperature of 37°C for 50 minutes. Two μl of synthesized cDNA was used for PCR amplification of 470-bp region from HCV 5’NCR along with core region by first round PCR amplification. The amplified first round PCR product were subjected to two second rounds of nested PCR amplifications. One with mix-I primers set and the second with mix-II primers set in a reaction volume of 10 μl. Mix-I had specific genotype primers set for 1a, 1b, 1c, 3a, 3c and 4 genotypes and mix- II contain specific genotype primers set for 2a, 2c, 3b, 5a and 6a.

Statistical Analysis

Given data was analyzed and the summary statistic was carried out by a statistical package, SPSS version 21.0. All variables results were given in the form of rates (%). All data are presented as mean values or number of patients. P-values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Result

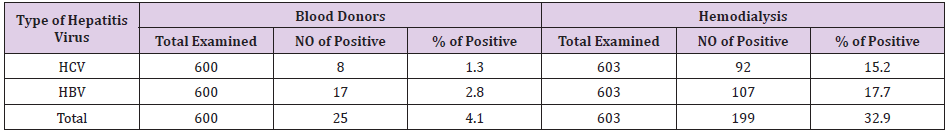

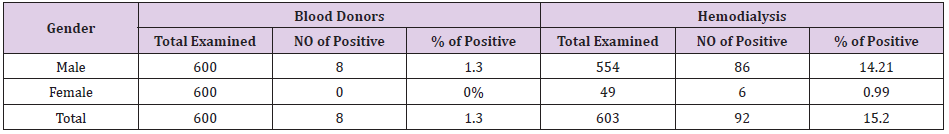

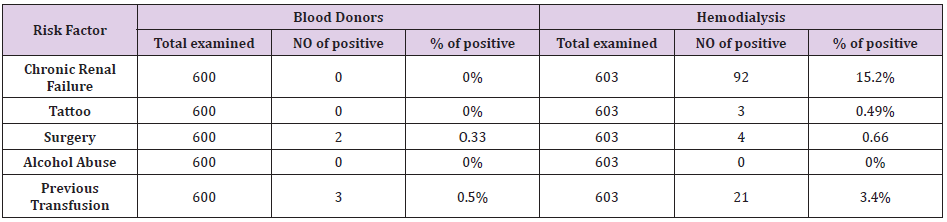

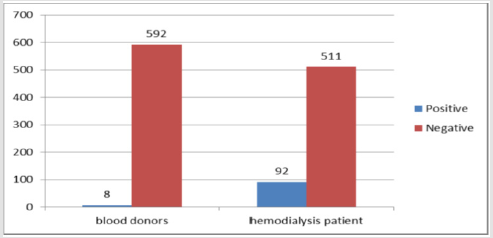

Out of 600 blood donors 8 (1.3%) were found to be positive for HCV antibodies and 17 (2.8%) for HBV antibodies. The hemodialysis patient showed higher seroprevalence of both HCV and HBV (15.2% and 17.7%) respectively Table 1. Male showed the higher seroprevalence of HCV antibodies (14.26%) compared to female (0.99%), Table 2, this might represent probability of Male were more exposed to HCV infection and its risk factor. The statistical analysis showed that it was significant scores at P-value = 0.00. The rate of HCV antibodies was significantly higher among hemodialysis patient compared to the blood donors, the difference in rates between those with previous history of infection were all statistically significant at P-values = 0.00 (Table 2). Table 3 summarizes the percentage or role of risk factors that might contribute to HCV infection, we found patients have chronic disease in about 92% this might represent probability of hemodialysis machine in transmission of the disease. While patients have received blood transfusion and who have a history of surgery represented 24% and 6% respectively.

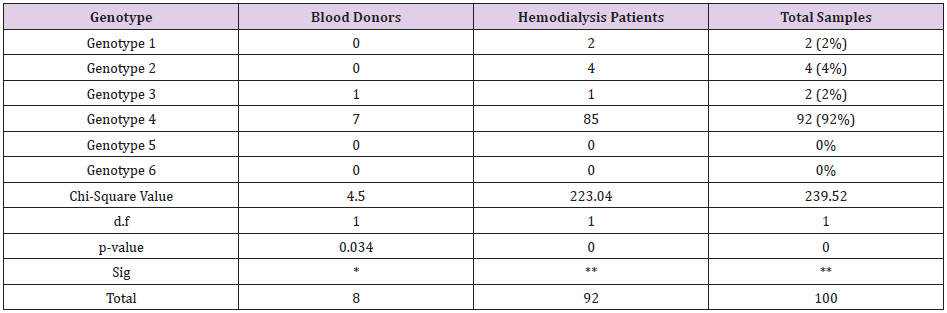

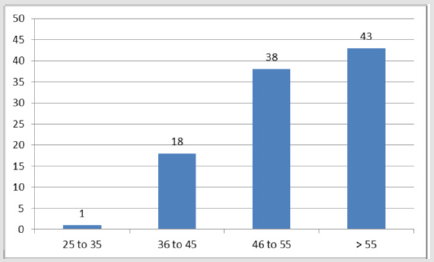

Tattooing 3% and alcohol take 0% have no role in predisposition to the disease statistically (Table 3). In this study, according to age groups the prevalence of infection with HCV increases remarkably from 46-55 years of age with highest prevalence of (43%) among the age over 55 years, Figure 1 that were statistically significant at P-value = 0.00 (Figure 1). RT-PCR was done for the 100 patients who were positive for anti HCV and the genotypes were determine, HCV genotype 4 was the predominant genotype (92%) followed by genotype 2 (4%), Genotype 1 (2%) and 3 (2%) in different groups, genotype 4 were significantly higher among both blood donors and hemodialysis patient. Genotype 5 and 6 were not detected in both blood donors and hemodialysis patient, genotypes 1 and 2 were not detected in blood donors, but in hemodialysis patient were detected. Patient with genotype 4 showed the highest viral load (9.3×106) copies/ml) (Table 4).

Viral load quantification was carried out by Taqman real time PCR system in all 100 HCV RNA positive patients and was compared between the four groups of genotypes. The average viral load of the patients infected with genotype 4 was higher than average viral load of the patients infected with genotypes 1.2 and 3 (2.76×103 - 9.3×106) copies/ml. Figure 2 shows the comparison between healthy blood donors and hemodialysis patients in rate of HCV infections, that were represented significant value when tested by Chi-square at P-value = 0.00, this may represent dialysis patients have an increased risk of exposure to parenteral transmitted hepatitis virus. Hemodialysis machine may also pose a risk HCV transmission (Figure 2).

Discussion

Out of the total number of blood donors examined the seroprevalence of HCV and HBV antibodies were (1.3%/2.8 %), respectively, when tested by ELISA using recombinant HCV - antigens. A similar study was previously done in Juba in Southern Sudan and 3% of the studied populations were found positive for HCV - antibodies (Mc Carthey et al.). Similarly [13] also reported the prevalence rates of HBV and HCV among different groups. Therefore, extensive recruitment of Saudi and young donors should help ensure a long-term increase in the blood supply without jeopardizing safety. Another study concluded that the prevalence of HCV infection in the population recruited from different health centers in Jordan was relatively low and estimates a prevalence of 0.42% among all age groups and 0.56% among those aged >15 years old [14,15]. Low values of both this study and others suggest that the rate of HCV infection is not high in healthy blood donors.

In this study HCV infection have been found high among hemodialysis patients (15.2%), when tested by ELISA using recombinant HCV - antigens, while 107 (17.7%) of HBV positive antibodies were found when tested using same technique. This is in agreement with [16]. Similarly [12,17] also reported that the prevalence of HCV - infection among dialysis patients is generally matched higher than that among healthy blood donors. Dialysis patients have an increased risk of exposure to parenteral transmitted hepatitis virus. Hemodialysis machine may pose a risk HCV transmission among HCV - antibodies positive patients. Again, results are in agreement with those obtained by [18]. However, the dialysis process itself and the level of hygienic standard may influence the risk level of HCV infection. Another study in Saudi reported that the overall of anti-HCV antibodies was in 7.3% (1124/15323) of the examined individuals [13].

Abdel Aziz F et al. reported that the high incidence of anti-HCV (24.3%) was estimated in Egypt of the total samples (973/3,999). This represented the highest reported in a community-based study inclusive of all age groups as well as reflected that HCV were endemic in Egypt [19]. Another study demonstrated high prevalence of anti- HCV in hemodialysis units in Al Gharbiyah in Egypt. It showed that 824 out of 2351 patients (35%) were positive for anti-HCV, and they encourage strict application of preventive strategies for HCV infection in all health institutes, especially hemodialysis units [20]. Nucleic acid amplification has become one of the most valuable tools in clinical medicine, especially for the diagnosis of infectious diseases with PCR being the most widely used because of its reliability. The distribution of HCV genotypes vary according to the geographical region. Genotypes 1-3 are widely distributed throughout the world [21]. Subtype 1a is prevalent in North and South America, Europe, and Australia [22,23].

Subtype 1b is common in North America and Europe [24,25], and is also found in parts of Asia. Genotype 2 is present in most developed countries [26] but is less common than genotype 1. HCV genotype 4 appears to be prevalent in North Africa and the Middle East. In India, HCV genotypes show differing distributions in different geographic regions. In north India, HCV genotypes 1, 2 and 3 have been detected with genotype 3 being the predominant one [27,28]. Data from south India showed high occurrence of genotype 1 followed by 3 [29]. The present study showed genotype type 4 (92%) to be the most common followed by type 2 (4%), genotype type 1and 3 (2%). The probability of a relapse after cessation of therapy is higher in patients with high HCV RNA copy numbers prior to therapy. The correlation between HCV genotypes and viral load remains controversial; in some studies, high titer viremia was correlated with advanced liver stage [30] while others found no correlation with either histology, viremia or aminotransferase activity [31,32]. However, the association between HCV genotypes and severe liver disease may be due to its long history of infection rather than intrinsically high pathogenicity.

Quantitative determination of HCV level in patient serum or plasma is an indirect measure of the extent of viremia and has been used a measure of response to antiviral drug. In the present study the viral load in patients with genotype 4 was significantly higher than those with genotypes 2 and 3. This might be due to more efficient viral replication of genotype 4 as compared to the others. The availability of effective antiviral therapy for hepatitis C has increased the need for molecular detection and quantification of hepatitis C viral particles. Because of the use of viral kinetics during polyethylene glycol interferon-ribavirin therapy and the development of specific new anti-hepatitis C virus (anti-HCV) drugs, assessment of the efficacy of anti-HCV drugs needs to be based not on end-point PCR assays but on real-time PCR. The predominance of HCV genotype 4 in our population confirms the predominance of HCV genotype 4 in UAE and most of the Arab countries in the Middle East [33].

There is extensive documentation of viral HCV RNA detection through RT-PCR, even in sero-negative cases [29,34] In one study by Baker, et al. [35] 316 serum samples were subjected to HCV antibody detection by ELISA and RIBA tests and HCV RNA detection by RT-PCR assay. The false positivity of HCV-Ab by ELISA and RIBA, when compared with RT-PCR, was reported as 5%, 3.9%, and 0% for blood donors, hemodialysis patients, and HIV-HCV coinfected cases, respectively. While comparing ELISA with RT-PCR, the false positivity was 10%, 5.9%, and 0%, respectively, for blood donors, hemodialysis patients, and HIV-HCV coinfected cases, thus delineating the importance of using the RT-PCR for HCV RNA to avoid false-negative results. HCV is transmitted primarily through the parenteral route and source of infection include injection, drug abuse, needle stick accidents and transfusion of blood and its biproducts. Dentists practicing oral surgery, practitioners of folk medicine and those involved in hairdressing and tattooing are also at higher risk for HCV.

In our study, the predominant risk factors associated with the HCV infection were dialysis patients, blood transfusion, and surgery and followed by with tattooing. However, the risk of progression to serious liver disease may be more likely in transfused patients than in non-transfused patients, due to exposure to higher viral load. Our data differ from that published from United States, Europe, and from our country [35,36]. In some studies, high titre viremia was correlated with advanced liver stage [30] while others found no correlation with either histology, viraemia or aminotransferase activity. Therefore, real-time PCR remains a cost- and time effective molecular technique of choice accompanied by sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis and prognosis of HCV, especially latent cases [37-40].

Conclusion

a) Of the 600 healthy blood donors screened for the presence of anti-HCV/HBV antibodies, 8/17 (1.3%/2.8%) were positive respectively.

b) A total of 603 hemodialysis patients screened for the same antibodies using the same technique 92/107 (15.2%/17.7%) were found positive for HCV/HBV antibodies respectively.

c) The males showed higher prevalence rates (94%) than females (6%) when screened by ELISA techniques.

d) The present study highlighted that genotype 4 (92%) is the predominant genotype in this geographical region followed by genotype 2.

e) The severity of liver disease was more in genotype 4 as assessed by higher viral load.

f) About the role of risk factors that might contribute to HCV infection, we found patients have chronic disease in about 92% this might represent probability of hemodialysis machine in transmission of the disease. While patients have received blood and who have a history of surgery represented 24% and 6% respectively, but alcohol take, and tattooing have no role in predisposition to the disease in various groups studied

g) The average viral load of the patients infected with genotype 4 was higher than average viral load of the patients infected with genotypes 1.2 and 3.

Acknowledgement

Thanks to all the patients for their cooperation in the study, as well as my colleagues and co-authors.

References

- Kuo G, Choo QL, Alter HJ, Gitnick GL, Redeker AG, et al. (1989) An assay for circulating antibodies to a major etiologic virus of human non-A, non-B hepatitis. Science 244(4902): 362-364.

- Aach RD, Yomtovian RA, Hack M (2000) Neonatal and pediatric posttransfusion hepatitis C: A look back and a look forward. Pediatrics 105(4 Pt 1): 836-842.

- Tsatsralt-Od B, Takahashi M, Endo K, Buyankhuu O, Baatarkhuu O, et al. (2006) Infection with hepatitis A, B, C, and delta viruses among patients with acute hepatitis in Mongolia. J Med Virol 78(5): 542-550.

- Houghton M, Weiner A, Han J, Kuo G, Choo QL (1991) Molecular biology of the hepatitis C viruses: implications for diagnosis, development and control of viral disease. Hepatology 14(2): 381-388.

- Bean P, Olive M (2001) Molecular principles underlying hepatitis C virus diagnosis. Am Clin Lab 20(5): 19-21.

- Ferreira MR, Lonardoni MV, Bertolini DA (2008) Hepatitis C: serological and molecular diagnosis and genotype in haemophilic patients at the Regional Hemocenter of Maringa, Maringa PR Brazil. Haemophilia.

- Zein NN (2000) Clinical significance of hepatitis C virus genotypes. Clin Microbiol Rev 13(2): 223-235.

- Koretz RL, Gluud C (2009) Prolonged therapy for hepatitis C with low dose peginterferon. N Engl J Med 360: 1151-1153.

- Baumert TF, Wellnitz S, Aono S, Satoi J, Heroin D, et al. (2000) Antibodies against hepatitis C virus-like particles and viral clearance in acute and chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 32(3): 610-617.

- Pearlman BL (2004) Hepatitis C infection: a clinical review. South Med J 97: 364- 374.

- Idrees M (2001) Common genotypes of hepatitis C virus present in Pakistan. Pak J Med Res 40: 46-49.

- Taura Y, Fujiyama S, Kawano S, Sato S, Tanaka M, et al. (1995) Clinical evaluation of titration of hepatitis C virus core antibody and its subclasses. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 10: 270-276.

- Ahmed S Abdel Moneim, Bamaga MS, Gaber MG Shehab, Abdel Aziz SA Abu Elsaad, Fayssal M Farahat (2012) HCV Infection among Saudi Population: High Prevalence of Genoye 4 and Increased Viral Clearance Rate. Plos One 7(1): e29781.

- Al Traif I, Al Balwi MA, Abdulkarim I, Handoo FA, Aqhalmdi HS, et al. (2013) HCV genotypes among 1013 Saudi nationals: A multicenter study. Ann Saudi Med 33(1): 10-12.

- Hamoudi W, Ali SA, Abdallat M, Estes CR, Razavi HA (2013) HCV infection prevalence in a population recruited at health centers in Jordan. J Epidemiol Glob Health 3(2): 67-71.

- Suliman SM , Fessaha S, El Sadig M, El-Hadi MB, Lambert S, et al. (1995) Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in hemodialysis patients in Sudan. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 6: 154-156.

- Sato S, Fujiyama S, Chikazawa H, Tanaka M (1995) Antibodies generated against hepatitis C virus (HCV) core antigen: IgM and IgA antibody against HCV core. Nihon Rinsho 53 Suppl: 253-259.

- Brian JG, Pereira, Edgar L Milford , Robert LKirkman, et al. (1992) Prevalence of hepatitis C virus RNA in organ donors positive for hepatitis C antibody and in the recipients of their organs. N Engl J Med 327: 910-915.

- Abdel Aziz F, Habib M, Mohamed MK, Abdel Hamid M, Gamil F, et al. (2000) Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in a community in the Nile Delta: population description and HCV prevalence. Hepatology 32(1): 111-115.

- Khodir SA, Alghateb M, Okasha KM, El Saed Salaby S (2012) Prevalence of HCV infections among hemodialysis patients in Al Gharbiyah Governorate, Egypt. Arab J Nephrol Transplant 5(3): 145-147.

- Simmonds P, Holmes EC, Cha TA, Chan SW, McOmish F, et al. (1993) Classification of hepatitis C virus into six major genotypes and a series of subtypes by phylogenetic analysis of the NS-5 region. J Gen Virol 74 (Pt 11): 2391-2399.

- Ana María Rivas Estilla, Paula Cordero Pérez, Karina del Carmen Trujillo Murillo, Javier Ramos-Jiménez,Carlos Chen López, et al. (2008) Genotyping of hepatitis C virus (HCV) in infected patients from Northeast Mexico. Ann Hepatol 7: 144-147.

- Trujillo-Murillo K, Rincón Sánchez AR, Martínez Rodríguez H, Bosques Padilla F, Ramos Jiménez J, et al. (2008) Acetylsalicylic acid inhibits hepatitis C virus RNA and protein expression through cyclooxygenase 2 signaling pathways. Hepatology 47: 1462-1472.

- Forns X, Fernandez Llama P, Pons M, Coasta J, Ampurdanes S, et al. (1997) Incidence and risk factors of hepatitis C virus infection in a haemodialysis unit. Nephrol Dial Transplant 12(4): 736-740.

- Lopez Labrador FX, Ampurdanes S, Forns X, Castells A, Saiz JC, et al. (1997) Hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotypes in Spanish patients with HCV infection: Relationship between HCV genotype 1b, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 27(6): 959-965.

- Pouillot R, Lachenal G, Pybus OG, Rousset D, Njouom R (2008) Variable epidemic histories of hepatitis C virus genotype 2 infection in West Africa and Cameroon. Infect Genet Evol 8: 676-681.

- Verma S, Goldin RD, Main J (2008) Hepatic steatosis in patients with HIV-Hepatitis C Virus coinfection: Is it associated with antiretroviral therapy and more advanced hepatic fibrosis? BMC Res Notes 1: 46.

- Verma V, Chakravarti A, Kar P (2008) Genotypic characterization of hepatitis C virus and its significance in patients with chronic liver disease from Northern India. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 61(4): 408-414.

- Raghuraman S, Shaji RV, Sridharan G, Radhakrishnan S, Chandy G, Ramakrishna BS, et al. (2003) Distribution of the different genotypes of HCV among patients attending a tertiary care hospital in south India. J Clin Virol 26: 61-69.

- Adinolfi LE, Utili R, Andreana A, Tripodi MF, Marracino M, et al. (2001) Serum HCV RNA levels correlate with histological liver damage and concur with steatosis in progression of chronic hepatitis C. Dig Dis Sci 46(8): 1677-1683.

- Gretch D, Corey L, Wilson J, Carithers R, Busch M, et al. (1994) Assessment of hepatitis C virus RNA levels by quantitative competitive RNA polymerase chain reaction: High-titer viremia correlates with advanced stage of disease. J Infect Dis 169(6): 1219-1225.

- Hagiwara H, Hayashi N, Mita E, Naito M, Kasahara A, et al. (1993) Quantitation of hepatitis C virus RNA in serum of asymptomatic blood donors and patients with type C chronic liver disease. Hepatology 17(4): 545-550.

- Alfaresi MS (2011) Prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotypes among positive UAE patients. Mol Biol Rep 38(4): 2719-2722.

- Chowdhury A, Santra A, Chaudhuri S, Satya Gopal M, Naik TN, et al. (2003) Hepatitis C virus infection in the general population: A community-based study in West Bengal, India. Hepatology 37(4): 802-809.

- Bakr I, Rekacewicz C, El Hosseiny M, Ismail S, El Daly M, et al. (2006) Higher clearance of hepatitis C virus infection in females compared with males. Gut 55(8): 1183-1187.

- Zaller N, Nelson KE, Aladashvili M, Badridze N, del Rio C, et al. (2004) Risk factors for hepatitis C virus infection among blood donors in Georgia. Eur J Epidemiol 19: 547-553.

- Jimenez MR, Urbie SF, Guillen LP, Garza CL, Hernandez CG (2010) Distribution of HCV genotypes and HCV RNA viral load in different geographical regions of Mexico. Annals Hepatology 9(1): 33-39.

- Mahaney K, Tedeschi V, Maertens G, Di Bisceglie AM, Vergalla J, et al. (1994) Genotypic analysis of hepatitis C virus in American patients. Hepatology 20: 1405-1411.

- Podzorski RP (2002) Molecular testing in the diagnosis and management of hepatitis C virus infection. Arch Pathol Lab Med 126: 285-290.

- Zein NN, Persing D (1996) Hepatitis C genotypes: Current trends and future implications. Mayo Clin Proc 71(5): 458-462.

Research Article

Research Article