Abstract

The research in the field of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine is exponentially growing to meet the demands for organ transplantation. The advantage of tissue engineering over conventional organ transplantation is the personalized development of whole organ or a particular part of the organ. To meet these organ demands, there are various approaches of tissue engineering such as traditional approach of using scaffold to grow cells and advanced 3D printing technology. The inkjet bioprinters are used along with bio-ink for bio-fabrication of different organs. The other bio-printing techniques such as extrusion-based and laser-assisted bio-printing can also be employed based on the requirement. The extracellular matrix (ECM) materials are used as a bio-ink but are limited largely to non-vascularized organs. The decellularized extracellular matrix (dECM) bio-inks are the recent advancement in the field which can be employed to generate the vascular organs like lungs and blood vessels. Even though tissue engineering shows a promising future there are various issues to be dealt with including ethics, approval from regulatory bodies and high cost of the technology.

Introduction

Organ transplantation has been the only feasible option for millions of people around the world with organ failure, and this problem is further challenged with increasing wait list for the organ transplantation and increase in mortality rate due to organ failure [1]. The issues associated with organ transplantation are complicated by finding a suitable donor for organ transplantation and storing it for a longer period of time [2]. According to the U.S government on organ donation and transplantation report, more than 100,000 patients are in the 2019 waiting list for organ transplantation and the organ donor shortage is at its peak than ever [3].

Tissue engineering is considered as the “holy grail” in the medical field and is growing at the fast pace allowing the tailormade organs to be an alternative and a viable solution to replace failed organs [4,5]. Tissue engineering has made the dream come to reality of having a fully functional artificially produced organ. Every year, there is exponential increase in the number of publications in the field of tissue engineering and regenerative medicines [6,7]. Although the non-vascularized organs such as skin [4,8], urinary bladder [9], urinary tract [10], bone [11] and blood vessels [12] are commercially available, thick vascularized organs such as liver, kidney and heart are still far from reality [1,13]. Commercial applications of tissue engineering are high and versatile [14]. It will help the world not just to solve the problem of organ donor scarcity for transplantation but can also be used for research purposes, for example, to study the effect of drug toxicity on different organs [7], and to study pharmacokinetics of a drug [13,15-17]. Research to create artificially engineered organs is carried out in different research laboratories around the world and successful treatments by bio fabricated organs has been reported [18]. According to Lee et al (2013), scaffold market was 4.75 million US dollars year which is expected cross more than 10 million US dollars by 2020; whereas market for stem cell will cross 11 billion US dollars by 2020 [19]. Apart from medical applications, many researchers around the world are exploring possibilities to produce leather and meat artificially through bio fabrication techniques [20,21]. The idea of bio fabrications is also being tested to produce microelectronics and biosensor [22].

Traditional Tissue Engineering

The idea of grafting or organ transplantation is not new. First skin grafting can be traced back to 3000 BC in India [23]. Although, the foundation of tissue engineering was laid by Dr. Ross in 1907 [24]. Dr. Ross studied nerve fiber development from embryonic tissue [25]. After four decades, in the year 1948, the first artificial kidney was made. Although it was a failure but conceived the idea of tissue engineering to produce artificial organs [17]. From early 1950s to 1960s, numerous articles were published on tissue assembly on which the present regenerative medicine and tissue engineering is established [23]. The tissue engineering can be defined as the methodology to replace the damaged tissues or organs with new tissues or working organ [26,27]. There are three ways by which it can be achieved:

a. Damaged cells can be replaced with new cells,

b. Injecting specific growth factors such as nerve growth factor (NGF), brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), neutrophin-3 (NT-3) and recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein 2 (rhBMP-2) as the differentiation marker; and

c. Growing entire organ artificially in vitro [28].

The first two methods are useful when damage is minimum, but to third method can be employed when there is need to replace larger part of organ or whole organ. The organ can be grown either as tissue scaffolds using 3D bioprinter or recolonization of decolorized organ. The major challenge in tissue engineering is to mimic the microenvironment of extracellular matrix and to arrange different cell types correctly when multiple cell types are present [29].

Growing cells in a scaffold is a traditional method of tissue engineering [30,31]. In this method, cells are seeded in the scaffold, which are usually porous and allowed to mature in the bioreactor [32]. The scaffold mimics the extracellular matrix of the cells. Extracellular matrix (ECM) is very important for the cell as it allows the cells to interact, provides nutrients and supplies oxygen [33]. Scaffold is typically made of either synthetic or natural polymers to provide the structural design and property of the organs [14,26,34]. Though this methodology is successful, but it has some shortcomings as well. This is not suitable for vascularized organs, as the cells in these organs are situated over the 200μm of vascular structure [35,36]. Blood vessels help in transfer of nutrient and oxygen which pose a major threat to the cell differentiation and maturation [37]. The second problem is when the cells are seeded in the scaffold, at times they do not adhere to the scaffold. Finally, synthetic grafts are prone to bacterial infections and thrombin formations [35].

Advances in Tissue Engineering

In 1985, 3D printing technology was patented. Three years later, Kelbe et al (1988) published a paper on 3D positioning of the cells, or “Conscribing” [38]. Initially, 3D printing was used for printing of the scaffold and cells were seeded in it. Shortcomings of the scaffold-based technology have motivated researchers to find other strategies [39]. The need of organs for transplant has not been fulfilled by organ donations and therefore need to regenerate organs through tissue engineering is gaining popularity. Tissue engineering has the ability to revolutionize the medical field with the bio fabricated organs and tissues [28,40]. In 1995, 3D printing technology and regenerative medicine converged together and gave rise to new era of 3D organ printing. Bio fabrication is defined as the process of using living cells, biomaterials, extracellular matrices and molecules to generate complex living as well as non-living biological products [24]. 3D printing provides more mechanical stability and nutrition diffusion than that of scaffold and applying 3D printing technology, tissues of different shapes and sizes can be fabricated [39,41].

In 2003, Inkjet bioprinter was introduced [42]. Bio-inkjet printer is similar to that of the desktop printer but in the cartridge, it consists of bioink [42]. Bioinks are the ECM materials such as fibrin, hormones and growth factors that are printed as layers and cells are deposited in it [43]. It also requires a computer-aided software for deposition of the cells. Bioprinting technology involves three processes: Preprocess, process and post process. In the preprocessing step, blueprint of the organ and tissue is designed with the help of computer [44]. After designing, processing takes place. Bioprinter prints layers of cells over ECM. In the last step, bioreactor is used for tissue maturation and differentiation. The main challenges in 3D bioprinting are lack of growth factors needed for the cell differentiation [45], production of the branched vascular network [29] where new blood vessels are grown with having same structure and biological function [46], and scarcity of the technical aspect of bioprinting process such as material and resolution of bioprinting [29]. 3D printing technology provides more cell to cell interactions and it closely mimic the indigenous microenvironment for tissue growth [47]. After two-decades, Organovo launched the first commercial bioprinter in the market [48]. Due to its expectation of usefulness in the field of organ transplantation and drug studies, many companies have launched commercial bioprinters, and Stryker had invested around 400 million US dollars in 2016 [49].

Apart from bio-inkjet there are other two bio-printing techniques such as extrusion-based bio-printing and laser-assisted bio-printing [50]. The extrusion-based bio-printing is simple technique with high cell density as compare to other bio-printing with few limitations like time consuming and less resolution [51]. The laser-assisted bio-printing is a technique with high resolution and accuracy, where the bio-printing is assisted with the help of laser beam aided with the computer aided design (CAD) [52]. Parallelly, decellularization process was considered as one of the primary ways to produce artificial organs. The main idea is to decellularized the organ and repopulate with the host stem cells. Though the small organs such as skin [53], heart valve [54] and vascular patches [55], cartilage [56] have been decellularized earlier, the first decellularization of whole organ was done.

In the year 2008. This was achieved by completely removing cells from the organ. Decellularization is done by three processes. (i) Chemical or enzymatic approach. (ii) Mechanical approach and (iii) Combination approach. In the first approach surfactants and acids are used to remove the host cells. Sometimes enzymes such as DNase are used to assist the reaction. While chemicals deteriorate the cell, enzymes are used to degrade the DNA of the cell. Chemical methods are effectives in removing the cells, but it also destroys the signal protein which are important for biochemical pathways. Hence in order to protect the biochemical property mechanical approach is exploited. In this approach, cells are destroyed using temperature and pressure. But mechanical methods are not effective in destroying the host genetic which leads to tissue rejection. Both chemical and mechanical methods have its own advantages and disadvantages. Therefore, in order to improve the effectiveness of the process both the methods are combined [57]. In the recolonization process stem cells are seeded and allowed to grow in bioreactor [58-62].

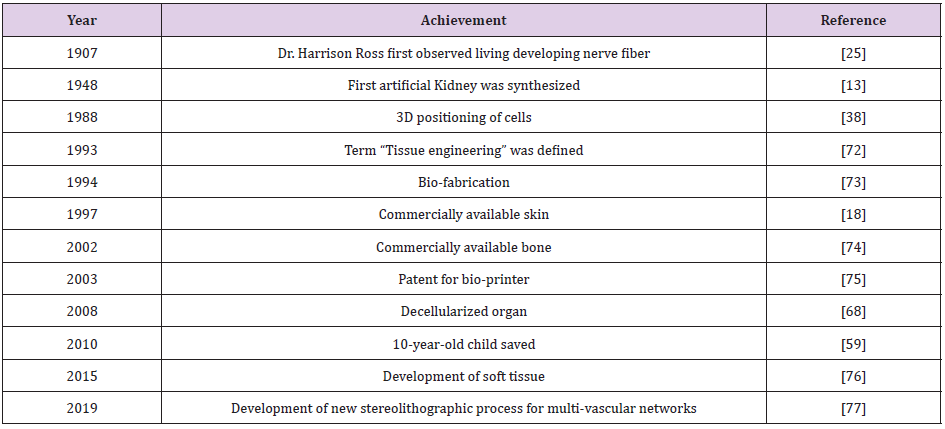

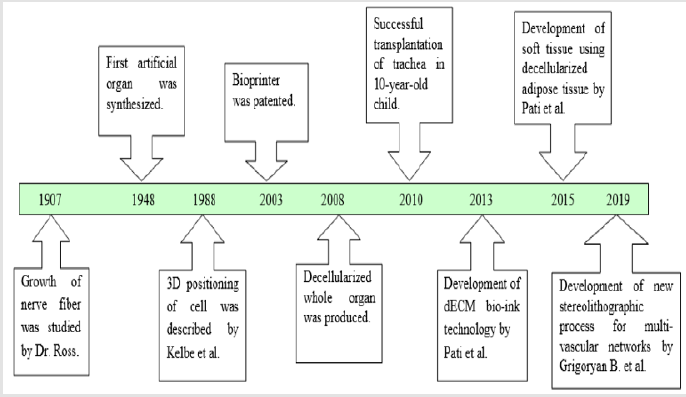

Production of vascularized organ decellularize organs gave hope to reach the reality of producing functional organ. Many decellularized vascular rich organs such as liver [63], kidney [64], lungs [65] and urethra [66] were synthesized in the later years. A 3-year-old child was treated with engineered trachea in 2010. Within a couple of years, more research was conducted on decellularized methods. It is shown that when the decellularized organ was introduced into the body, it grows by 57% [67]. The first decellularized whole heart was produced in the year 2008 [68]. This was performed in rat and transplanted successfully. Decellularized kidney was produced from rhesus monkey and repopulated with other cells. Adult lung tissue is yet another example with limited regeneration capacity. Petersen et al (2010) harvested lung tissue from adult Fischer 344 rat, removed cellular components, retained the scaffold of extracellular matrix that retains the hierarchical branching structures of airways and vasculature, seeded endothelial cells and transplanted these cells into rat. Their findings suggested implanted cells with functional for gas exchange activity and repopulation of acellular matrix is a feasible approach to produce engineered lung [69]. These and other studies have attracted interest of many scientists because of less immunogenicity observed with the decellularization technology. In the process of decellularization, all the materials responsible for immunogenicity are removed, thus immunogenicity is greatly reduced. The other reason is whole organs can be produced by this methodology. Unlike organ printing, where only sheet or miniature of organs are possible. ECM is intact in this methodology which helps in nutrient transport and signal transduction. Shortcoming of this technology is availability of the organs. So far, the decellularized organs have been obtained from either cadaver or animals. Decellularization also reduce the tensile property [70]. A good example of its success story comes from successful trachea transplantation in a 10-year-old boy [59]. Two patients were treated with decellularized human extracellular matrix scaffold who were suffering from non-Hodgkin lymphoma and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, post chemotherapy they had ovarian failure, they conceived after successful small invasive transplantation of ovarian tissue which was cryopreserved with the dECM scaffold [71-81] (Tables 1 & 2) ( Figure 1).

Table 2: Difference between Scaffold, Decellularization, Scaffold free and dECM bioink [5,39,78-81].

DECM Bio ink

In order to overcome the shortcomings of the decellularized organs and bio inkjet printing organ new technology is emerged by merging both. In this method, organs are decellularized first [82,83] and then ECM from decellularized organs is used as the bioink for the bioprinter [79]. Decellularized matrix is considered as next generation bioink [78,80]. Pati et al (2014) developed this technology and year later in 2015 they developed soft tissue using decellularized adipose tissue [83]. By this method, a layer of 400- 300μm thickness is made and stacked up to 10 layers which is twice the size of the traditional printing method [76]. This technology is so far found to be useful in producing the whole organ and the mechanical property of decolorized organs was improved by hybrid technology, which uses re-absorbable polymer scaffold [84].

Future Aspect

Advances in tissue engineering research and its methodology lead to the formation of scaffold to bioprinter and then to the decellularized organs. More research in methodologies are overcoming the shortcomings of previous ones. Improving knowledge in the biology of regeneration, development in microelectronics and 3D printing technology is helping in further overcoming the hurdles [85]. Production of commercially available organs is not the distant future anymore. FDA regulations [26], associated cost [86] and ethical issues [87,88] may delay the technology, however research trend suggests death due to organ scarcity will be reduced in foreseeable future [89].

Conflict of interest

None of the authors declares any conflicts of interest in this study.

References

- Mikos AG, Herring SW, Ochareon P, Elisseeff J, Lu HH, et al. (2006) Engineering complex tissues. Tissue Eng 12(12): 3307-3339.

- Ventola CL (2014) Medical Applications for 3D Printing: Current and Projected Uses. P & T : a peer-reviewed journal for formulary management39(10): 704-711.

- (2019) Organ Donation Statistics.

- Vielreicher M, Schürmann S, Detsch R, Schmidt MA, Buttgereit A, et al. (2013) Taking a deep look: modern microscopy technologies to optimize the design and functionality of biocompatible scaffolds for tissue engineering in regenerative medicine. J R Soc Interface10(86): 20130263.

- Chan BP, KW Leong (2008) Scaffolding in tissue engineering: general approaches and tissue-specific considerations. European spine journal: official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society 17 Suppl 4(Suppl 4): 467-479.

- Baiguera S, L Urbani, C Del Gaudio (2014) Tissue engineered scaffolds for an effective healing and regeneration: reviewing orthotopic studies. BioMed research international: 398069-398069.

- Luo X (2012) Biofabrication in Microfluidics: A Converging Fabrication Paradigm to Exploit Biology in Microsystems. J Bioeng Biomed Sci 2(2).

- Yannas IV, Burke JF, Orgill DP, Skrabut EM (1982) Wound tissue can utilize a polymeric template to synthesize a functional extension of skin. Science 215(4529): 174-176.

- Atala A1, Bauer SB, Soker S, Yoo JJ, Retik AB (2006) Tissue-engineered autologous bladders for patients needing cystoplasty. Lancet 367(9518): 1241-1246.

- Vaidya M (2015) Startups tout commercially 3D-printed tissue for drug screening. Nat Med 21(1): 2.

- Place ES, ND Evans, MM Stevens (2009) Complexity in biomaterials for tissue engineering. Nat Mater 8(6): 457-470.

- L'Heureux N, Pâquet S, Labbé R, Germain L, Auger FA. (1998) A completely biological tissue-engineered human blood vessel. The FASEB Journal 12(1): 47-56.

- Gauvin R, Guillemette M, Dokmeci M, Khademhosseini A (2011) Application of microtechnologies for the vascularization of engineered tissues. Vascular Cell 3(1): 24.

- Brahatheeswaran Dhandayuthapani YY, Toru Maekawa, D Sakthi Kumar (2011) Polymeric Scaffolds in Tissue Engineering Application: A Review. International Journal of Polymer Science: 8.

- Zhao Y, Yao R, Ouyang L, Ding H, Zhang T, et al. (2014) Three-dimensional printing of Hela cells for cervical tumor model in vitro. Biofabrication 6(3):035001.

- Snyder JE, Hamid Q, Wang C, Chang R, Emami K, et al. (2011) Bioprinting cell-laden matrigel for radioprotection study of liver by pro-drug conversion in a dual-tissue microfluidic chip. Biofabrication 3(3): 034112.

- Bywaters EGL, AM Joekes (1948) The artificial kidney; its clinical application in the treatment of traumatic anuria. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 41(7): 420-426.

- Mac Neil S (2007) Progress and opportunities for tissue-engineered skin. NATURE 445(7130): 874-880.

- Seou Lee, Taehoon Kwon, Eun Kyung Chung, Joon Woo Lee (2014)The market trend analysis and prospects of scaffolds for stem cells. Biomaterials research 18: 11.

- Wegrzyn TF, M Golding, RH Archer (2012) Food Layered Manufacture: A new process for constructing solid foods. Trends in Food Science & Technology 27(2): 66-72.

- Godoi FC, S Prakash, BR Bhandari (2016) 3d printing technologies applied for food design: Status and prospects. Journal of Food Engineering 179: 44-54.

- Liu Y, Kim E, Ghodssi R, Rubloff GW, Culver JN, et al. (2010) Biofabrication to build the biology–device interface. Biofabrication 2(2): 022002.

- Berthiaume F, TJ Maguire,ML Yarmush (2011) Tissue engineering and regenerative medicine: history, progress, and challenges. Annu Rev Chem Biomol Eng 2: 403-430.

- Mironov V, Trusk T, Kasyanov V, Little S, Swaja R, et al. (2009) Biofabrication: a 21st century manufacturing paradigm. Biofabrication 1(2): 022001.

- Harrison Rose G, Greenman MJ, Mall Franklin P, Jackson CM (1907) Observations of the living developing nerve fiber. The Anatomical Record 1(5): 116-128.

- Hopkins R (2007) Cardiac surgeon's primer: tissue-engineered cardiac valves. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Ann: 125-135.

- Groll J, Boland T, Blunk T, Burdick JA, Cho DW, et al. (2016) Bio fabrication: reappraising the definition of an evolving field. Biofabrication 8(1): 013001.

- Ma PX (2004) Scaffolds for tissue fabrication. Materials Today 7(5): 30-40.

- Murphy S, A Atala (2014) 3D Bioprinting of Tissues and Organs. Nature biotechnology 32(8):773-785.

- Dababneh AB, IT Ozbolat (2014) Bioprinting Technology: A Current State-of-the-Art Review. Journal of Manufacturing Science and Engineering 136(6).

- Sears NA, Seshadri DR, Dhavalikar PS, Cosgriff-Hernandez E (2016) A Review of Three-Dimensional Printing in Tissue Engineering. Tissue Eng Part B Rev 22(4):298-310.

- Martin I, D Wendt, M Heberer (2004) The role of bioreactors in tissue engineering. Trends Biotechnol 22(2): 80-86.

- Hurtley S (2009) Spatial cell biology. Location, location, location. Introduction. Science 326(5957): 1205.

- Peng ZHAO, Haibing GU, Haoyang MI, Chengchen RAO, Jianzhong FU, et al. (2018) Fabrication of scaffolds in tissue engineering: A review. Frontiers of Mechanical Engineering 13(1): 107-119.

- Ferris CJ, Gilmore KG, Wallace GG, In het Panhuis M. (2013) Biofabrication: an overview of the approaches used for printing of living cells. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 97(10): 4243-4258.

- Rouwkema J, NC Rivron, CA van Blitterswijk (2008) Vascularization in tissue engineering. Trends Biotechnol26(8): 434-441.

- Chang WG, LE Niklason (2017)A short discourse on vascular tissue engineering. npj Regenerative Medicine 2(1): 7.

- Klebe RJ (1988) Cytoscribing: A method for micropositioning cells and the construction of two- and three-dimensional synthetic tissues. Experimental Cell Research 179(2): 362-373.

- Norotte C, Marga FS, Niklason LE, Forgacs G (2009) Scaffold-free vascular tissue engineering using bioprinting. Biomaterials 30(30): 5910-5917.

- Mir TA, M Nakamura (2017) Three-Dimensional Bioprinting: Toward the Era of Manufacturing Human Organs as Spare Parts for Healthcare and Medicine. Tissue Eng Part B Rev 23(3): 245-256.

- Kang HW, Lee SJ, Ko IK, Kengla C, Yoo JJ, et al. (2016) A 3D bioprinting system to produce human-scale tissue constructs with structural integrity. Nature Biotechnology 34(3): 312-319.

- Rod R Jose, Maria J Rodriguez, Thomas A Dixon, Fiorenzo Omenetto, David L Kaplan (2016) Evolution of Bioinks and Additive Manufacturing Technologies for 3D Bioprinting. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering 2(10): 1662-1678.

- Hinderer S, SL Layland,K Schenke-Layland (2016) ECM and ECM-like materials- Biomaterials for applications in regenerative medicine and cancer therapy. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 97: 260-269.

- Pearce D, et al. (2019) Applications of Computer Modeling and Simulation in Cartilage Tissue Engineering. Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine.

- Ozbolat IT (2015) Bioprinting scale-up tissue and organ constructs for transplantation. Trends in Biotechnology 33(7): 395-400.

- Song HG, Rumma RT, Ozaki CK, Edelman ER, Chen CS (2018) Vascular Tissue Engineering: Progress, Challenges, and Clinical Promise. Cell stem cell 22(3): 340-354.

- Lenke Horváth, Yuki Umehara, Corinne Jud, Fabian Blank, Alke Petri-Fink, et al. (2015) Engineering an in vitro air-blood barrier by 3D bioprinting. Scientific Reports 5(1):7974.

- Choudhury D, S Anand, M Win Naing (2018) The Arrival of Commercial Bioprinters - Towards 3D Bioprinting Revolution! International Journal of Bioprinting: 4.

- Combellack, E ZM. Jessop IS Whitaker (2018) 20 - The commercial 3D bioprinting industry, in 3D Bioprinting for Reconstructive Surgery, DJ Thomas, ZM Jessop, and IS Whitaker, (Eds.), 2018, Woodhead Publishing: pp:413-421.

- Mandrycky C, Wang Z, Kim K, Kim DH (2016) 3D bioprinting for engineering complex tissues. Biotechnol Adv 34(4):422-434.

- Derakhshanfar S, Mbeleck R, Xu K, Zhang X, Zhong W, et al. (2018) 3D bioprinting for biomedical devices and tissue engineering: A review of recent trends and advances. Bioactive materials 3(2): 144-156.

- Ajay Vikram Singh, Mohammad Hasan Dad Ansari, Shuo Wang, Peter Laux ,Andreas Luch, et al. (2019)The Adoption of Three-Dimensional Additive Manufacturing from Biomedical Material Design to 3D Organ Printing. Applied Sciences 9(4): 811.

- Chen RN, Ho HO, Tsai YT, Sheu MT (2004) Process development of an acellular dermal matrix (ADM) for biomedical applications. Biomaterials 25(13): 2679-2686.

- Schmidt CE, JM Baier (2000) Acellular vascular tissues: natural biomaterials for tissue repair and tissue engineering. Biomaterials 21(22):2215-2231.

- Cho SW, Park HJ, Ryu JH, Kim SH, Kim YH, et al. (2005) Vascular patches tissue-engineered with autologous bone marrow-derived cells and decellularized tissue matrices. Biomaterials 26(14): 1915-1924.

- Elder BD, DH Kim, KA Athanasiou (2010) Developing an articular cartilage decellularization process toward facet joint cartilage replacement. Neurosurgery 66(4): 722-727.

- Elena Garreta, Roger Oria, Carolina Tarantino, Mateu Pla-Roca, Patricia Prado, et al. (2017) Tissue engineering by decellularization and 3D bioprinting. Materials Today 20(4): 166-178.

- Badylak SF, D Taylor, K Uygun (2011) Whole-organ tissue engineering: decellularization and recellularization of three-dimensional matrix scaffolds. Annu Rev Biomed Eng 13:27-53.

- Kalathur M, S Baiguera, P Macchiarini (2010) Translating tissue-engineered tracheal replacement from bench to bedside. Cellular and molecular life sciences: CMLS 67(24): 4185-4196.

- Crapo PM, TW Gilbert,SF Badylak (2011) An overview of tissue and whole organ decellularization processes. Biomaterials 32(12):3233-3243.

- Gilbert TW, TL Sellaro,SF Badylak (2006)Decellularization of tissues and organs. Biomaterials 27(19): 3675-3683.

- Panagiotis Maghsoudlou, Giorgia Totonelli, Stavros P Loukogeorgakis,Simon Eaton, Paolo De Coppi(2013)A decellularization methodology for the production of a natural acellular intestinal matrix. Journal of visualized experiments: JoVE (80):50658.

- Faulk DM, JD Wildemann, SF Badylak (2015) Decellularization and cell seeding of whole liver biologic scaffolds composed of extracellular matrix. J Clin Exp Hepatol 5(1): 69-80.

- Karina H Nakayama, C Chang I Lee, Cynthia A Batchelder, Alice F Tarantal (2013) Tissue Specificity of Decellularized Rhesus Monkey Kidney and Lung Scaffolds. PLOS ONE 8(5): e64134.

- Paula N Nonaka, Juan J Uriarte, Noelia Campillo, Vinicius R Oliveira, Daniel Navajas, et al. (2016) Lung bioengineering: physical stimuli and stem/progenitor cell biology interplay towards biofabricating a functional organ. Respiratory Research 17(1):161.

- Irina N Simões, Paulo Vale, Shay Soker, Anthony Atala, Daniel Keller, et al. (2017) Acellular Urethra Bioscaffold: Decellularization of Whole Urethras for Tissue Engineering Applications. Scientific reports 7: 41934-41934.

- Zeeshan Syedain, Jay Reimer, Matthew Lahti,James Berry, Sandra Johnson, et al. (2016) Tissue engineering of acellular vascular grafts capable of somatic growth in young lambs. Nature communications 7: 12951-12951.

- Ott HC, Matthiesen TS, Goh SK, Black LD, Kren SM, et al. (2008) Perfusion-decellularized matrix: using nature's platform to engineer a bioartificial heart. Nat Med 14(2): 213-221.

- Petersen TH, Calle EA, Zhao L, Lee EJ, Gui L, Raredon MB, et al. (2010) Tissue-engineered lungs for in vivo implantation. Science 329(5991): 538-541.

- Partington L, Mordan NJ, Mason C, Knowles JC, Kim HW, et al. (2013) Biochemical changes caused by decellularization may compromise mechanical integrity of tracheal scaffolds. Acta Biomater 9(2): 5251-5261.

- Oktay K, Bedoschi G, Pacheco F, Turan V, Emirdar V (2016) First pregnancies, live birth, and in vitro fertilization outcomes after transplantation of frozen-banked ovarian tissue with a human extracellular matrix scaffold using robot-assisted minimally invasive surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 214(1): 94.e1-9.

- Sándor GK (2013) Tissue engineering: Propagating the wave of change. Annals of maxillofacial surgery 3(1): 1-2.

- Fritz Monika, Belcher Angela M, Radmacher Manfred, Walters Deron A,Hansma, et al. (1994)Flat pearls from biofabrication of organized composites on inorganic substrates. Nature 371(6492):49-51.

- Parikh SN (2002) Bone graft substitutes: past, present, future. J Postgrad Med 48(2): 142-148.

- Mironov V, Boland T, Trusk T, Forgacs G, Markwald RR. (2003) Organ printing: computer-aided jet-based 3D tissue engineering. Trends Biotechnol 21(4): 157-161.

- Pati F, Ha DH, Jang J, Han HH, Rhie JW,et al. (2015)Biomimetic 3D tissue printing for soft tissue regeneration. Biomaterials 62:164-175.

- Grigoryan B, Paulsen SJ, Corbett DC3, Sazer DW, Fortin CL, et al. (2019) Multivascular networks and functional intravascular topologies within biocompatible hydrogels. Science 364(6439): 458-464.

- Kim BS, Kim H, Gao G, Jang J, Cho DW (2017) Decellularized extracellular matrix: a step towards the next generation source for bioink manufacturing. Biofabrication 9(3): 034104.

- Toprakhisar B, Nadernezhad A, Bakirci E, Khani N, Skvortsov GA, et al. (2018) Development of Bioink from Decellularized Tendon Extracellular Matrix for 3D Bioprinting. Macromolecular Bioscience 18(10): 1800024.

- Kabirian F, M Mozafari (2019) Decellularized ECM-derived bioinks: Prospects for the future. Methods.

- Sawkins MJ, Bowen W, Dhadda P, Markides H, Sidney LE, et al. (2013) Hydrogels derived from demineralized and decellularized bone extracellular matrix. Acta Biomater9(8): 7865-7873.

- Ge Gao , Jun Hee Lee , Jinah Jang,Dong Han Lee,Jeong‐Sik Kong,et al. (2017)Tissue Engineered Bio-Blood-Vessels Constructed Using a Tissue-Specific Bioink and 3D Coaxial Cell Printing Technique: A Novel Therapy for Ischemic Disease. Advanced Functional Materials 27(33): 1700798.

- Pati F, Jang J, Ha DH, Won Kim S, Rhie JW, et al. (2014) Printing three-dimensional tissue analogues with decellularized extracellular matrix bioink. Nature Communications 5(1): 3935.

- Johnson C, Sheshadri P, Ketchum JM, Narayanan LK, Weinberger PM, et al. (2016) In vitro characterization of design and compressive properties of 3D-biofabricated/decellularized hybrid grafts for tracheal tissue engineering. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 59: 572-585.

- Hollister SJ (2009) Scaffold engineering: a bridge to where? Biofabrication 1(1): 012001.

- Campbell PG,LE Weiss (2007) Tissue engineering with the aid of inkjet printers. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 7(8):1123-1127.

- Otto IA, Breugem CC, Malda J, Bredenoord AL (2016) Ethical considerations in the translation of regenerative biofabrication technologies into clinic and society. Biofabrication 8(4): 042001.

- Matthews KR, AS Iltis (2015) Unproven stem cell-based interventions and achieving a compromise policy among the multiple stakeholders. BMC Med Ethics 16(1): 75.

- Baharuddin AS, Aminuddin Ruskam, Mohammad Amir Wan Harun, Abdul Rahim Yacob (2014) Three-dimensional (3d) bioprinting of human organs in realising maqāsid al-shari'ah. Perintis E-Journal 4: 27-42.

Research Article

Research Article