Abstract

There are 10-20% cases of IgA vasculitis which precede only with abdominal symptoms. It’s clinically necessary to take non-infectious diseases into consideration when sick children are suffering from sustained abdominal symptoms without any infectious evidence from feces. For the purpose of it, some quick and precise test without much invasion should be considered. Endoscopic examination could be helpful to differentiate the gastro-intestinal presentations of systemic disease such as IgA vasculitis from other diseases in gastrointestinal tract as well as other imaging modalities. Here we report an interesting case where we finally could diagnose his illness as IgA vasculitis using lower gastrointestinal endoscopic imaging.

Keywords: IgA vasculitis; Henoch-Schönlein Purpura; Abdominal Phenotype; Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

Case Report

A 4-year-old boy presented with fever and abdominal pain one week before admission, and visited a pediatric practitioner, who diagnosed his manifestations as streptococcal pharyngitis. Despite antibiotic treatment, fever with recurrent emesis and watery stool continued without any improvement until his admission to our hospital. He had been introduced to receive further investigation and treatment in our hospital. His physical examination revealed intermittent low-grade fever and normal range of vital signs on admission. There looked slightly abdominal inflation without spontaneous pain or tenderness. No skin rash like petechiae or purpura was observed on his body or limbs. He apparently had no medical, social, and familial history. From his hospitalization bloody diarrhea started without any findings suggesting intussusception or bacterial colitis because abdominal ultrasonic examination was negative and repetitive stool cultures in addition to rapid tests for Vero toxin or viral antigens were all negative.

His laboratory tests showed: hemoglobin of 13.7 g/dL; leukocyte counts of 21.4×103 /μL; C-reactive protein of 0.36 mg/dL. 4 days after admission, his repeated blood tests identified that his inflammatory responses seemed progressive as leukocyte counts of 24.3×103 /μL and C-reactive protein of 0.94 mg/L, while his symptoms got worsen with increased bloody stool and recurrent abdominal angina with spiky fevers. His hemoglobin level slightly decreased to 11.6 g/dL and the value of coagulation factor XIII turned out to be only 33% (cut-off level < 70%). Abdominal plain CT scanning partially revealed the wall thickness of ileocecum. Any examinations of his feces had repeatedly shown all negative results except for fecal calprotectin: the antigen tests of Norovirus, Rotavirus, verodoxins, and clostridium difficile were negative, and even bacterial cultures including Yersinia species were also negative.

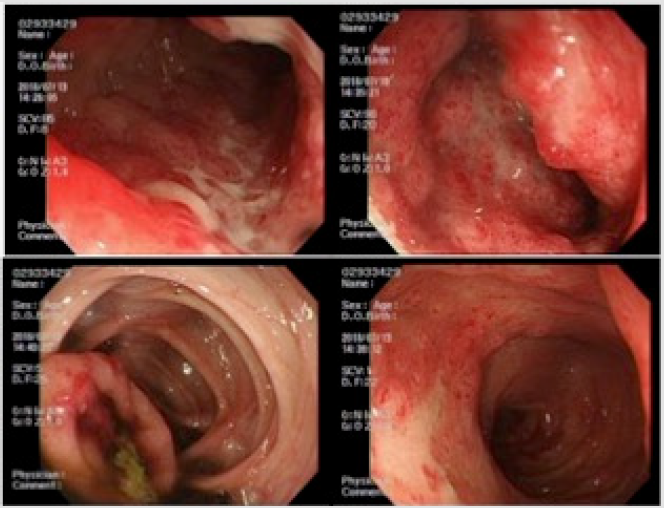

One week after admission, enhanced abdominal CT examination showed the lesion of possible leucocytes, followed by lower gastrointestinal endoscopic examination. The localized lesion in terminal ileum showing multiple linear ulcers with active bleeding was detected, which helped us become suspicious of IgA vasculitis rather than bacterial colitis (Figure 1). Based on our endoscopic analyses, we started systemic administration of prednisolone (2mg/kg/day) and cefotaxime, with total parenteral nutrition. His bloody stool and abdominal pain immediately vanished by systemic steroid therapy. After all, his pathological specimen of the lesions revealed the suggestive granulocytes in ileum wall, lymphangiectasia and mucosal erosion of small intestine with some IgA immune-stained findings. He finally had diagnosis of IgA vasculitis Henoch-Schönlein Purpura. After that, short-term steroid therapy was very effective. Now he is regularly checked up in our clinic without any evidence of recurrence beyond a year.

Figure 1: Inflamattion of ileum end captured by endoscopic examination: each figure revealed irregular ulcer with redness and edema in the ileocecal area, which became a clue to the diagnosis.

Discussion

IgA vasculitis, so-called Henoch-Schönlein Purpura, is acute small vasculitis featuring non-thrombocytopenic purpura, sometimes accompanied by arthritis, abdominal angina, or nephritis. Some infection, drug allergy, or food allergy might involve the etiology [1]. The incidence rate is reported to be about 1 per 10,000 people a year. Children from 3 to 7-year-old, 90% or more of whom are found below 10 years old, are susceptible to IgA vasculitis. Gastrointestinal symptoms include diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and bloody stool. Although abdominal symptoms often precede to other ones, distinguishing them from other common abdominal diseases is really difficult especially without raised purpura of lower extremities or buttocks: laparoscopic examination might be needed [2]. Pathological examination could help rule out the possibility of IBD like Crohn’s disease. We finally diagnosed his manifestations as IgA vasculitis due to no evidence of any other pathological causes through the whole examination.

Diagnostic criteria had been revised since ACR (American College of Rheumatology) first proposed it in 1990 [3]. Diagnosis of IgA vasculitis majorly consists of the evidence concerning skin lesions such as palpable purpura and more than one additional criterion such as arthrosis or nephritis, which leads to the sensitivity is 100% and the specificity is 87% during childhood referring to the classification criteria [4]. There reported to be a pitfall that abdominal symptoms may precede skin lesions in 10- 20% of patients especially in child cases [5], and such a case couldn’t meet the criteria like our case. Thus, there remain some reports that laparoscopic examination was needed [3]. Ultrasonography or CT examination would be helpful to roughly detect abdominal diseases; it could show any pathological findings of IgA vasculitis with gastrointestinal manifestation only in 21% of 261 pediatric patients [6]. On the other hand, gastrointestinal endoscopy is not only useful to directly find the lesions in gastrointestinal tract, but also to morphologically and microscopically detect the diseases by sampling the causal specimens. Endoscopic treatment for bleeding sites or polyps could be operated if necessary. Non-specific inflammatory findings are frequently observed with respect to biopsy of gastrointestinal lesions, so less useful findings are available for diagnosis as compared to skin biopsy [7,8]; however the endoscopic examination could strongly support clinical diagnosis after ruling out other gastrointestinal diseases such as bacterial colitis or IBD.

References

- Masanori A, Misako S, Naho K (2007) An adult case of Henoch-Schönlein purpura with prior abdominal symptoms. Clin Rheumatol 19: 255-267.

- Steven D, Nancy F (2010) Ileitis: When It Is Not Crohn’s Disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 12(4): 249-258.

- Hetland LE, Susrud KS, Lindahl KH (2017) Henoch-Schönlein Purpura: A Literature Review. Acta Derm Venereol 15: 97(10): 1160-1166.

- Yasuhiro N, Yasutaka K, Yumiko F (2016) Endoscopic findings in Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Progress of Digestive Endoscopy 89: 1.

- Chen MJ, Wang TE, Chang WH (2005) Endoscopic findings in a patient with Henoch-Schonlein purpura. World J Gastroenterol 21: 11(15): 2354-2356.

- Limi Huang, Li Sun, Chaosheng Lu, Yanke Zhu, Kefan Miao, et al. (2019) Int J Clin Exp Med 12(2): 2035-2041.

- Nei S, Nobuyuki S, Yuji H (2011) Case of Adult Onset Henoch-Schonlein Purpura with Gastrointestinal Lesions Especially More Severe in the Antrum of the Stomach. Gastroenterol Endosc 53: 1241-1251.

- Morris G, Perry W (1998) PEDIATRIC DIAGNOSIS Interpretation of Symptoms & Signs in Infants, Children, and Adolescents. W.B. SAUNDERS COMPANY 249-251.

Case Report

Case Report