Abstract

To investigate the presence of Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) in hepatic lesions and Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) in southeast Mexican patients, liver biopsies and resections specimens from HCC and hepatic lesions (cholestasis and steatosis, hepatitis and necrosis, fibrosis and cirrhosis) were collected and immunohistochemically examined. The expression of HBsAg and a liver tumor marker: Alpha-Fetoprotein (AFP) was quantified in liver specimens by quantitative and semiquantitative methods. The correlation between expression level of AFP and HBsAg and degree of liver injury was analyzed statistically. Expression of AFP was found in all hepatic lesions and HCC samples in a different intensity level. There was no significant difference of AFP positive area in each group analyzed. The HBsAg expression was detectable as a weak stain in samples of all groups. The age of patients with hepatic lesions in contrast to HCC did show a significant difference. The age mean was significant higher in HCC (55.9) with respect to hepatic lesions (38.2). In the patients without HCC, the proportion of HBsAg positive area was higher than in HCC group, and this difference was statistically significant. A negative correlation of HBsAg in hepatic lesions and hepatocellular carcinoma was found. AFP was detected in hepatic lesions and HCC; hence additional diagnosis techniques should be used in Mexican southeast patients to have an accurate diagnose and a clinical treatment. There was a negative correlation between HBsAg presence and degree of liver injury. However, supplementary molecular techniques in search of occult HBV infection in HCC patients must be developed.

Keywords: HVB; Hepatocellular Carcinoma; Hepatic Lesions; Alpha-Fetoprotein; HBsAg; Immunostaining

Abbreviations: HCC: Hepatocellular Carcinoma; HBV: Hepatitis B Virus; AFP: Alpha-Fetoprotein; HCV: Hepatitis C Virus; HBsAg: Hepatitis B surface Antigen; TMAs: Tissue Microarrays; HBx: Hepatitis B Virus X Protein; OBI: Occult HBV Infection

Introduction

The liver cancer is the third most deadly cancer worldwide, with more than 600,000 deaths annually [1]. HCC accounts for 90% of all liver cancers and the Asian and African populations are the most affected with this malignancy. México and South American countries display a poorly documented annual incidence of primary HCC [2,3]. Worldwide distribution of HCC correlates with high rates of HBV infection [4]. HBV is considered as a major risk factor for developing HCC [5-7]. Nevertheless, additional risk factors include Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) infection, obesity, cirrhosis, aflatoxin intake and hemochromatosis [8-12]. There are more than 350 million individuals chronically infected with HBV worldwide [13-15]. While active vaccination against HBV is a successful measure in Asian regions [16], Mexican population is not entirely protected by immunization programs [17,18]; hence chronic HBV infection remains an important public health issue. HBV causes transient and chronic liver infections. The transient infections can cause acute liver disease and approximately 0.5% of people suffer fulminant fatal hepatitis. Chronic infections may also have serious consequences and terminate in untreatable liver cancer [19,20]. The oncogenic capacity of HBV to enhance malignant transformation is due to interplay mechanisms of cell host defense against viral replication [21].

Moreover, the virus proteins them self-promote alterations of signal transduction pathways related to hepatocyte proliferation [22-24]. The immune-mediated liver damage contributes to hepatic pathogenesis [25]. The chronic liver inflammation (hepatitis) generated by HBV infection, stimulates continuous cycles of lowlevel liver cell destruction and regeneration that, over long periods of time, lead to hepatic lesions like steatosis, fibrosis, cirrhosis, and HCC [26]. The Hepatitis B Surface Antigen (HBsAg) and Alpha- Fetoprotein (AFP) are considered serum markers to HBV infection and HCC respectively. The HBsAg in a blood test indicates current HBV infection (acute or chronic) and the person can transmit the infection to others [27,28]. And the serum levels of AFP are correlated with the size and volume of the tumor at the time of diagnosis [29,30]. In Mexico, the impact of chronic HBV infection as etiologic factor on HCC is still unknown. Data about general chronic liver diseases prevalence underestimates the real outlook [31]. Although it is assumed that the majority of HCC reported in Mexico develops from alcohol-related cirrhosis, the incidence of viral hepatitis increased [32-34]. Alcohol consumption is the principal cause usually explored in a cirrhotic patient, and the assessment of a hepatic viral infection is not taken in consideration in all cases [31]. In accordance with Mexican Health Ministry and National Institute of Statistics and Geography reports, Veracruz is a southeast state that refers to record the highest rates of liver cancer mortality. Therefore, it is necessary to explore the presence of HBsAg and AFP levels in the hepatic lesions and HCC in southeast Mexican population.

Materials and Methods

Ethics

This work has been carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2000) of the World Medical Association, the Mexican General Health Law (latest reform 2011), the Regulation of the General Law on Health Research for Health (1987), and the Health Law of the State of Veracruz-Llave (latest reform 2008). Scientific and Ethics Hospital Committee approved this study (permission number: 005/2011).

Clinical Samples

Paraffin-embedded hepatic biopsies and resection samples from 69 patients (28 females, 41 males: mean age 42.3 ± 23.5 years) with HCC and hepatic lesions (cholestasis and steatosis, hepatitis and necrosis, fibrosis and cirrhosis) were selected since 1992 up to 2008 year from pathology department collection of the Hospital: Medical Specialty Center of Veracruz State Dr. Rafael Lucio. Only 94.2 % of patients had records of age and sex, and the remaining 5.8 % reported just the gender in the clinical records. Fifteen cases of HCC (6 females, 9 males: mean age 54.4 range 17-70 years), 24 cases of cholestasis and steatosis (6 females, 18 males: mean age 38.7 range 15-60 years), 9 of hepatitis and necrosis (4 females, 5 males: mean age 43 range 31-60 years), 5 cases of fibrosis (2 females, 3 males: mean age 30.2 range 0.5-60 years) and 16 cases of cirrhosis (10 females, 6 males: mean age 37.4 range 0-58 years). As a negative control (CN), a cervix tissue sample was used.

Anatomic-Histological Analysis

All specimens were sliced to hematoxylin-eosin staining for routine histological diagnosis. The histopathological examination was carried out and hepatic specimens were grouped according to the following pathological classification:

a) Cholestasis and steatosis

b) Hepatitis and necrosis

c) Fibrosis

d) Cirrhosis

e) HCC

In all cases two expert pathologists blindly reviewed and confirmed the diagnosis.

Tissue Microarray Design and Construction

In order to obtain the best magnification area to immunological analysis, three Tissue Microarrays (TMAs) with different spot diameters (1, 1.5 and 2 mm) were constructed. The TMAs were constructed by using a semi-automated array device (Veridiam, El Cajón, CA). Each one of paraffin-embedded tissue samples of all groups was represented in all three microarrays by duplicate. A board-certified pathologist selected tissue cores.

Immunohistochemical Staining and Quantification

Formalin-fixed paraffin liver sections (4 micron) were blocked for 1 h in 0.1% H2O2 in phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4. They were then incubated overnight with commercial monoclonal antibodies specific to anti-AFP and anti-HBsAg (Santa Cruz, Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), diluted 1:15 and 1:150 (V/V) respectively. After washing with phosphate-buffered saline, the primary antibody was detected using an avidin-biotin complex immunoperoxidase technique (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. No staining was observed when the primary antibody was substituted with mouse isotype control. The proportion of immunostaining positive area was calculated using image analysis software (Analysis Soft Imaging System, GmbH). A second analysis was a semiquantitative scoring method, it is based on grade staining: 0 (negative), 1(weak), 2 (moderate), and 3 (strong) as described by Zhang [35] and Chadha [36]. The final score was the total sum of the product of the staining intensity and its corresponding area percentage. For example, if a tumor showed 50% moderate staining and 50% strong staining, the final score would be (50X2)+(50X3)=250. A final score of at least 100 was considered positive expression [35].

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using PASW Statistics v.18 (www.spss.com) Proportions were compared using the X2 test or Fisher exact test when necessary. Medians and means were compared using the U of Mann-Whitney test or Student’s T test, respectively. We calculated Spearman correlation coefficients or Pearson depending on the result of normality test Kolmogorov-Srminov Z. A value of P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Staining Levels of AFP in Hepatic Lesions and Hepatocellular Carcinoma

The utility of AFP in serum as a tumor marker of HCC has been established. However, the specificity and sensibility of the test remains contradictory [37]. In order to know the AFP level in hepatic lesions and HCC of Mexican patients of the southeast, we analyzed the immunostaining of AFP in hepatitis and necrosis, steatosis and cholestasis, fibrosis, cirrhosis and HCC groups. We found a uniform AFP staining in hepatic parenchyma of HCC group (red arrow, HCC), with small groups of non-staining scattered cells in the liver tissue (black arrow, HCC). The presence of AFP in cirrhosis group was located in great areas of regenerative nodules (black arrow, cirrhosis), surrounded by fibrotic bridges (red arrow, cirrhosis). The cholestasis and steatosis group revealed a moderate AFP stain placed in macro vesicular steatosis areas with lipidcontaining vacuoles (red arrow, cholestasis and steatosis).

In the non-steatosis zones (black arrow, cholestasis and steatosis), the AFP presence was lower. The stain degree in this group was very similar to the one in the cirrhosis group, but lipid vacuoles that span a large space in the tissue create the effect of minor staining. A remarkable zonal presence of AFP in hepatitis and necrosis group was found in the hepatic parenchyma (red arrow, hepatitis and necrosis). It becomes evident that AFP expression is not produced by all hepatocytes in an inflammatory state. In the Fibrosis group, except for fibrous material areas around portal tracts (black arrow, Fibrosis), the AFP distribution is located in almost all the remaining hepatocytes (red arrow, fibrosis). As a control group (CN), a cervix sample was used. We can clearly observe there was no expression of AFP in the whole tissue.

Relatively Low HBsAg Intensity Level in Hepatic Lesions and HCC

As mentioned above, one of the main risk factors associated to HCC development is the HBV infection. The HBsAg is employed as a routine sero-test in the search for HBV infection (acute or chronic) diagnosis. The Figure, displayed a representative image from each group, on which we observed an HBsAg weak stain in hepatic lesions and HCC. The immunostaining of HBsAg showed brown-yellowish granules in the cytoplasm considered as a positive expression. The cervix tissue used as a negative control, did not show HBsAg stain (CN). In HCC group, clusters of HBsAg positive cells were scattered singly or gathered in some parts of the liver tissue (black arrow, 4 X). The presence of HBsAg was detectable in cytosol of the hepatocytes (black arrow, HCC 20 X). Each samples of cirrhosis group showed dissimilar patterns to HBsAg stain (black arrow, cirrhosis). In the samples where the HBsAg expression was shown, the quantity of HBsAg in the cytoplasm of individual cells varied somewhat from cell to cell. The HBsAg was distributed diffusely throughout the cytoplasm. In the cholestasis and hepatitis group characterized by lipids vacuoles, the HBsAg was sited in cytoplasmic areas from hepatocytes with macro vesicular steatosis zones. Interestingly, in hepatitis-necrosis and fibrosis groups (black arrows, hepatitis and necrosis; fibrosis), the HBsAg expression showed a few scattered positive cells. Outwardly, the HBsAg expression was much lower than usually found in liver tissue from other groups.

Equivalent Intensity Protein Levels of Manual and Automatic Quantification

The presence of HBsAg and AFP proteins, was quantified through two methods described before: a semiquantitative visual score [35] or a quantitation by image analysis software [38]. Both procedures provided a dataset for each group that were correlated by Spearman’s test. In (panel A), it is noted the parallel increment of HBsAg levels between HBsAg visual and automated scores in 74% (r=0.86; P < 0.0001). Likewise (panel B), a significant coefficient correlation was found between AFP visual and automated scores (r=0.71; P < 0.0001), which explain variability was 50%. Both correlations were positively linear. The panel C displays a representative image of the TMA with 1.5 mm diameter spots tissues and exemplify the semiquantitative scoring (visual) and the quantitative imaging methods. Based on the image analysis software, the total of 69 samples (100%) showed AFP detectable stain in liver tissue. The HBsAg expression was detectable as a weak stain in 68/69 (98.5%). However, applying the stringent manual method that considered a final score of at least 100 as a positive expression, we found a 90% of positive cases for AFP protein, and only the 17.8% of the total cases were positive to HBsAg expression. Due to significant coefficient correlation by Spearman test, between visual and automated procedure, we decided to use the dataset deployed by automated software for statistical analysis.

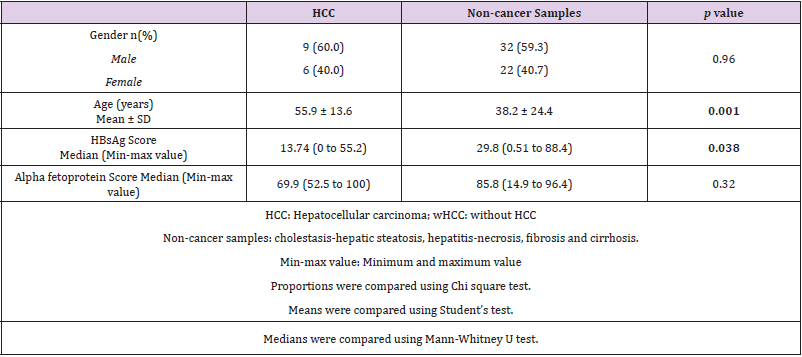

Demographic Characteristics of Patients with Hepatic Lesions and Hepatocellular Carcinoma

The patient demographic characteristics with hepatic lesions (non-cancer samples: cholestasis and steatosis, hepatitis and necrosis, fibrosis and cirrhosis) and HCC are summarized in two great groups (Table 1). There was a prevalence of male gender in both groups, although this difference was not significant. On the other hand, the age of patients with or without HCC did show a difference. The age mean was higher in HCC (55.9 ± 13.6) with respect to hepatic lesions (38.2 ± 24.4). In the non-cancer samples, the median of HBsAg positive area was higher than in HCC group. Finally, there was not difference of the AFP expression between HCC and non-cancer specimens.

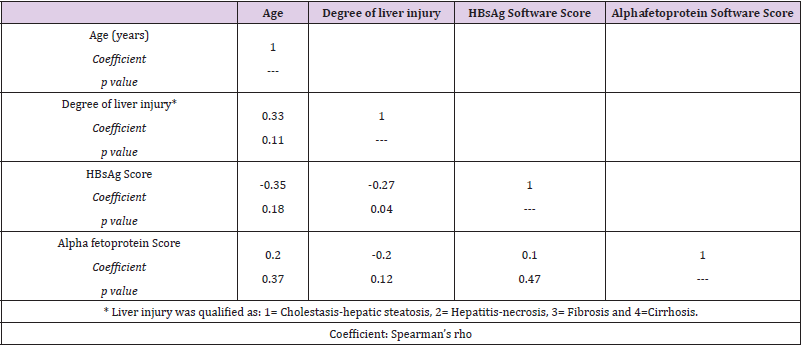

Correlation Between Age, Degree of Liver Injury and HBsAg-Alpha fetoprotein Score

In Table 2, we observed a correlation matrix including age, degree of liver injury evolution (1 = Hepatic Steatosis-Cholestasis, 2 = Hepatitis-Necrosis, 3 = Fibrosis, and 4 = Cirrhosis) and scores for HBsAg and AFP. The age of patients ordered in terms of liver injury evolution correlated significantly. On the other hand, the HBsAg expression was negatively correlated only with degree of liver injury (Spearman coefficient= -0.27, P < 0.05). Interestingly, the correlations between degree of liver injury and AFP expression were not correlated significantly.

Discussion

The sensitivity and specificity of serological AFP level as hepatic tumor marker have displayed a controversial setting, ranging from characteristics of the diagnostic test used [39], the racial differences in AFP effectiveness [40] even the virological status affects the efficiency of AFP in patients with HCC and chronic liver diseases [41]. Our data indicated a non-exclusive expression of AFP in HCC and a widespread minor or major presence in each group tested. In accordance with our results, in a previous report the AFP levels rise further as the grade of liver steatosis increases [42]. The increased serum AFP level in patients with severe fatty liver was attributed to hepatic inflammation and/or fibrosis as underlying cause. Other chronic liver diseases (viral hepatitis, hepatic fibrosis, and cirrhosis), are connected with augmented AFP level [43]. It has even been reported in other malignancies such as gastric cancer [44-46]. The AFP expression in non-cancerous liver pathologies and non-liver tissues, converge in a permanent inflammatory condition regardless of its etiology. The previous studies and our results support that using only the measurement of AFP is insufficient for HCC diagnosis. In fact, nowadays the evaluation of fucosylated AFP is being used along with the standard imaging studies to improve accurate diagnosis [47,48].

Mexico is a Latin-American country considered part of low endemic HBV infection area. This situation may be due to diverse factors such as recent addition of the HBsAg detection from 1980 [49], to commercially available detection methods with a low sensibility and specificity used in healthcare institutions [50], to a new unsystematized epidemiological national surveillance [51] and occult HBV infection [34]. Nevertheless, although the national immunization program started since 1999, the population of sexually active adolescents and adults not covered by the program have a risk of becoming infected with HBV. The incidence and prevalence of liver diseases in Mexico have increased in the last two decades [32] and it will increase further [52]. Veracruz is one of the southeast Mexican states with major increase of liver cancer mortality [32]. However, there are not enough regional studies in which the etiology has been analysed. Maybe this could be explained due to do not exist a national specific program for hepatocellular carcinoma epidemiological surveillance.

The HBsAg, since its discovery in Australia in 1967 [53] is employed in both Mexico and the entire world, as a qualitative diagnostic marker for acute or chronic HBV infection. All three forms of HBsAg antigen (Dane particle, filamentous particle and spherical particle) can be detected in serum with commercial assays for diagnosis test in clinical practice [54]. The presence of the HBsAg in chronic liver diseases endorses the concept of HBV infection as a risk factor for HCC development. The steatosis is a common histopahtological feature of HBV chronic infection [55] caused by Hepatitis B Virus X Protein (HBx), which stimulates lipid accumulation in hepatic cells mediated by sterol regulatory element binding protein 1 and PPAR gamma [56]. The progression from steatohepatitis to HCC has been documented formerly. In our study, we found a higher level of HBsAg in hepatic lesions (steatosis, hepatitis, fibrosis and cirrhosis) than in HCC. Therefore, our results agree with literature about the effect of HBV infection on early stages in HCC development. Nevertheless, it was not found an increase level of HBsAg in HCC patients with respect to the noncancerous hepatic lesions. These results caused us awareness since it is described that the presence and replication of HBV determines and enhances the malignant transformation. Concerning this, it has been documented that some individuals who are chronically infected with HBV and eventually lose HBsAg, but HBV DNA remains in the sera at low replicative and transcriptional levels allowing inflammation, facilitating progression of disease [57,58].

This spontaneous sorcerous was associated to older age but could be implicated the HBV genotypes and geographic areas of high endemicity [59]. Moreover, HBsAg mutations described above [60], hamper the diagnostic performance and limit HBV detection with a determinant mutation [61]. The failure to detect HBsAg due to mutations justifies the HBsAg clearance and explains an Occult HBV Infection (OBI). OBI is defined as serologically or tissular undetectable HBsAg, despite HBV DNA circulating [62]. The discovery of OBI was made in order to elucidate the HBV transmission, even by blood components negative for HBsAg of donor’s transfusions. Although we haven´t analyzed the HBV DNA to consider an occult HBV infection as a possible explanation results, there are several investigations describing an OBI among native Mexicans and southeast citizens [34,63], where the genotype H was the main circulating HBV strain with mutations in core region [64]. In conclusion, AFP was detected in hepatic lesions and HCC; hence additional diagnosis techniques should be used in Mexican southeast patients to accurate diagnostic and clinical treatment. There was a positive significant correlation between age and degree of liver injury. Also found a negative correlation between HBsAg presence and degree of liver injury. However, supplementary molecular techniques to test presence of occult HBV infection in HCC patients must be developed.

Acknowledgement

We wish to thank Quintanar Jurado V, Fattel Fazenda S, Macías Pérez JR, Hernández-García S, Garma Rivera C, González S, Chavarría Xicoténcatl PM, and FR Martínez for helpful assistance. Grant performed this study: PROMEP 103.5/10/5006.

References

- Schutte K, Bornschein J, Malfertheiner P (2009) Hepatocellular carcinoma-epidemiological trends and risk factors. Digestive diseases 27(2): 80-92.

- Lavanchy D (2004) Hepatitis B virus epidemiology, disease burden, treatment and current and emerging prevention and control measures. Journal of viral hepatitis 11(2): 97-107.

- Mondragon Sanchez R, Ochoa Carrillo FJ, Ruiz Molina JM (1997) Hepatocellular carcinoma. Experience at the Instituto Nacional de Cancerologia. Rev Gastroenterol Mex 62(1): 34-40.

- Liaw YF, Brunetto MR, Hadziyannis S (2010) The natural history of chronic HBV infection and geographical differences. Antiviral therapy 15(Suppl 3): 25-33.

- Sanyal AJ, Yoon SK, Lencioni R (2010) The etiology of hepatocellular carcinoma and consequences for treatment. The oncologist 15(Suppl 4): 14-22.

- Michielsen P, Ho E (2011) Viral hepatitis B and hepatocellular carcinoma. Acta gastro-enterologica Belgica 74(1): 4-8.

- Kew MC (2010) Epidemiology of chronic hepatitis B virus infection, hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatitis B virus-induced hepatocellular carcinoma. Pathologie-biologie 58(4): 273-277.

- El-Serag HB (2001) Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Liver Dis 587-107.

- Leong TY, Leong AS (2005) Epidemiology and carcinogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma. HPB (Oxford) 7(1): 5-15.

- Marrero CR, Marrero JA (2007) Viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Archives of medical research 38: 612-620.

- Coleman WB (2003) Mechanisms of human hepatocarcinogenesis. Current molecular medicine 3(6): 573-588.

- Sherman M (2005) Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology, risk factors, and screening. Seminars in liver disease 25(2): 143-154.

- Herzer K, Sprinzl MF, Galle PR (2007) Hepatitis viruses: live and let die. Liver Int 27(3): 293-301.

- Liu CJ, Kao JH (2007) Hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology and pathogenic role of viral factors. J Chin Med Assoc 70(4): 141-145.

- Lupberger J, Hildt E (2007) Hepatitis B virus-induced oncogenesis. World J Gastroenterol 13(1): 74-81.

- Zhou YH, Wu C, Zhuang H (2009) Vaccination against hepatitis B: the Chinese experience. Chinese medical journal 122(1): 98-102.

- Villasis Keever MA, Pena LA, Miranda Novales G (2001) Prevalence of serological markers against measles, rubella, varicella, hepatitis B, hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency virus among medical residents in Mexico. Preventive medicine 32(5): 424-428.

- Fay OH (1990) Hepatitis B in Latin America: epidemiological patterns and eradication strategy. The Latin American Regional Study Group. Vaccine 8 (Suppl): S100-106.

- Beasley RP (1988) Hepatitis B virus. The major etiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer 61(10): 1942-1956.

- Yu MW, Chen CJ (1994) Hepatitis B and C viruses in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology 17(2): 71-91.

- Hsieh YH, Hsu JL, Su IJ (2011) Genomic instability caused by hepatitis B virus: into the hepatoma inferno. Frontiers in bioscience : a journal and virtual library 17: 2586-2597.

- Kew MC (2011) Hepatitis B virus x protein in the pathogenesis of hepatitis B virus-induced hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology 26(Suppl 1): 144-152.

- Benhenda S, Cougot D, Buendia MA (2009) Hepatitis B virus X protein molecular functions and its role in virus life cycle and pathogenesis. Advances in cancer research 103: 75-109.

- Hussain SP, Schwank J, Staib F (2007) TP53 mutations and hepatocellular carcinoma: insights into the etiology and pathogenesis of liver cancer. Oncogene 26(15): 2166-2176.

- Chisari FV, Ferrari C (1995) Hepatitis B virus immunopathogenesis. Annual review of immunology 13: 29-60.

- Chisari FV, Isogawa M, Wieland SF (2010) Pathogenesis of hepatitis B virus infection. Pathologie-biologie 58(4): 258-266.

- de Franchis R, Meucci G, Vecchi M (1993) The natural history of asymptomatic hepatitis B surface antigen carriers. Annals of internal medicine 118(3): 191-194.

- Togo S, Arai M, Tawada A (2011) Clinical importance of serum hepatitis B surface antigen levels in chronic hepatitis B. Journal of viral hepatitis 18(10): e508-515.

- Tangkijvanich P, Anukulkarnkusol N, Suwangool P (2000) Clinical characteristics and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: analysis based on serum alpha-fetoprotein levels. Journal of clinical gastroenterology 31: 302-308.

- Johnson PJ (2001) The role of serum alpha-fetoprotein estimation in the diagnosis and management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clinics in liver disease 5(1): 145-159.

- Torres Poveda K, Burguete Garcia AI, Madrid Marina V (2011) Liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in Mexico: impact of chronic infection by hepatitis viruses B and C. Annals of hepatology : official journal of the Mexican Association of Hepatology 10(4): 556-558.

- Mendez Sanchez N, Garcia Villegas E, Merino Zeferino B (2010) Liver diseases in Mexico and their associated mortality trends from 2000 to 2007: A retrospective study of the nation and the federal states. Annals of hepatology : official journal of the Mexican Association of Hepatology 9(4): 428-438.

- Alvarez Munoz T, Bustamante Calvillo E, Martinez Garcia C (1989) Seroepidemiology of the hepatitis B and delta in the southeast of Chiapas, Mexico. Archivos de investigacion medica 20(2): 189-195.

- Roman S, Tanaka Y, Khan A (2010) Occult hepatitis B in the genotype H-infected Nahuas and Huichol native Mexican population. Journal of medical virology 82(9): 1527-1536.

- Zhang Y, Wang S, Li D (2011) A systems biology-based classifier for hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosis. PLoS One 6(7): e22426.

- Chadha KS, Khoury T, Yu J (2006) Activated Akt and Erk expression and survival after surgery in pancreatic carcinoma. Annals of surgical oncology 13(7): 933-939.

- Barletta E, Tinessa V, Daniele B (2005) Screening of hepatocellular carcinoma: role of the alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and ultrasonography. Recenti progressi in medicina 96(6): 295-259.

- Garcia Roman R, Salazar Gonzalez D, Rosas S (2008) The differential NF-kB modulation by S-adenosyl-L-methionine, N-acetylcysteine and quercetin on the promotion stage of chemical hepatocarcinogenesis. Free Radic Res 42(4): 331-343.

- Gupta S, Bent S, Kohlwes J (2003) Test characteristics of alpha-fetoprotein for detecting hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with hepatitis C. A systematic review and critical analysis. Annals of internal medicine 139(1): 46-50.

- Nguyen MH, Garcia RT, Simpson PW (2002) Racial differences in effectiveness of alpha-fetoprotein for diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis C virus cirrhosis. Hepatology 36(2): 410-417.

- Trevisani F, D Intino PE, Morselli Labate AM (2001) Serum alpha-fetoprotein for diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic liver disease: influence of HBsAg and anti-HCV status. Journal of hepatology 34(4): 570-575.

- Babali A, Cakal E, Purnak T (2009) Serum alpha-fetoprotein levels in liver steatosis. Hepatology international 3(4): 551-555.

- Chen CH, Lin ST, Kuo CL (2008) Clinical significance of elevated alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) in chronic hepatitis C without hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepato-gastroenterology 55(85): 1423-1427.

- Chun H, Kwon SJ (2011) Clinicopathological characteristics of alpha-fetoprotein-producing gastric cancer. Journal of gastric cancer 11(1): 23-30.

- Adachi Y, Tsuchihashi J, Shiraishi N (2003) AFP-producing gastric carcinoma: multivariate analysis of prognostic factors in 270 patients. Oncology 65(2): 95-101.

- Ishigami S, Natsugoe S, Nakashima H (2006) Biological aggressiveness of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP)-positive gastric cancer. Hepato-gastroenterology 53(69): 338-341.

- Shiraki K, Takase K, Tameda Y (1995) A clinical study of lectin-reactive alpha-fetoprotein as an early indicator of hepatocellular carcinoma in the follow-up of cirrhotic patients. Hepatology 22(3): 802-807.

- Kobayashi M, Hosaka T, Ikeda K (2011) Highly sensitive AFP-L3% assay is useful for predicting recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after curative treatment pre- and postoperatively. Hepatology research : the official journal of the Japan Society of Hepatology 41(11): 1036-1045.

- Vazquez Flores JA, Valiente Banuet L, Marin y Lopez RA (2006) Safety of the blood supply in Mexico from 1999 to 2003. Revista de investigacion clinica; organo del Hospital de Enfermedades de la Nutricion 58: 101-108.

- Roman S, Panduro A, Aguilar Gutierrez Y (2009) A low steady HBsAg seroprevalence is associated with a low incidence of HBV-related liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in Mexico: a systematic review. Hepatology international 3(2): 343-355.

- Panduro A, Melendez GE, Fierro NA (2011) Epidemiology of viral hepatitis in Mexico. Salud publica de Mexico 53(Suppl 1): S37-45.

- Mendez Sanchez N, Villa AR, Chavez Tapia NC (2005) Trends in liver disease prevalence in Mexico from 2005 to 2050 through mortality data. Annals of hepatology : official journal of the Mexican Association of Hepatology 4(1): 52-55.

- Blumberg BS, Gerstley BJ, Hungerford DA (1967) A serum antigen (Australia antigen) in Down's syndrome, leukemia, and hepatitis. Annals of internal medicine 66(5): 924-931.

- Lee JM, Ahn SH (2011) Quantification of HBsAg: basic virology for clinical practice. World journal of gastroenterology : WJG 17(3): 283-289.

- Petta S, Camma C, Di Marco V (2011) Hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance are associated with severe fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis caused by HBV or HCV infection. Liver international: official journal of the International Association for the Study of the Liver 31(4): 507-515.

- Kim KH, Shin HJ, Kim K (2007) Hepatitis B virus X protein induces hepatic steatosis via transcriptional activation of SREBP1 and PPARgamma. Gastroenterology 132(5): 1955-1967.

- Simonetti J, Bulkow L, McMahon BJ (2010) Clearance of hepatitis B surface antigen and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in a cohort chronically infected with hepatitis B virus. Hepatology 51(5): 1531-1537.

- Yuen MF, Wong DK, Fung J (2008) HBsAg Seroclearance in chronic hepatitis B in Asian patients: replicative level and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 135(4): 1192-1199.

- Villa E, Fattovich G (2010) No inflammation? No cancer! Clear HBV early and live happily. Journal of hepatology 52(5): 768-770.

- Arababadi MK, Pourfathollah AA, Jafarzadeh A (2011) Hepatitis B virus genotype, HBsAg mutations and co-infection with HCV in occult HBV infection. Clinics and research in hepatology and gastroenterology 35(8-9): 554-559.

- Gerlich WH (2004) Diagnostic problems caused by HBsAg mutants-a consensus report of an expert meeting. Intervirology 47(6): 310-313.

- Said ZN (2011) An overview of occult hepatitis B virus infection. World journal of gastroenterology : WJG 17(15): 1927-1938.

- Garcia Montalvo BM, Farfan Ale JA, Acosta Viana KY (2005) Hepatitis B virus DNA in blood donors with anti-HBc as a possible indicator of active hepatitis B virus infection in Yucatan, Mexico. Transfusion medicine 15(5): 371-378.

- Garcia Montalvo BM, Ventura Zapata LP (2011) Molecular and serological characterization of occult hepatitis B infection in blood donors from Mexico. Annals of hepatology: official journal of the Mexican Association of Hepatology 10(2): 133-141.

Research Article

Research Article