Abstract

Introduction: Technological advances in imaging studies have led to an increase in early diagnosis of benign and focal liver tumors such as simple cyst, hemangioma, Focal Nodular Hyperplasia (UFH), adenoma.

Objective: To evaluate the prevalence of benign liver lesions in the largest reference center for hepatology in the Rio Grande do Norte - University Hospital Onofre Lopes / Northeast Brazil.

Methods: Cross-sectional descriptive study with a quantitative approach. The prevalence of focal benign hepatic lesions in patients from a referral center for hepatology in the Brazilian Northeast was evaluated. The sample was chosen by convenience, based on the analysis of patient records.

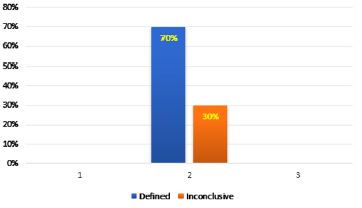

Results: A total of 12,333 medical records were analyzed, and 640 selected with the initial diagnosis of focal liver injury. Of these, 70% had a definite diagnosis, and 30% remained inconclusive. Of all the focal lesions diagnosed, the most common was the simple cyst, followed by hemangioma, adenoma, and UFH.

Conclusion: The present study made it possible to identify the prevalence of benign liver lesions in the hepatology department, and its relevance was the acquisition of epidemiological knowledge on the subject, as an additional tool to establish a diagnosis. Thus, it is expected that the health team has the opportunity to guide and reassure their patients about the benignity of the case, thus reducing waiting time or subjecting them to unnecessary diagnostic or surgical procedures.

Keywords: Benign Hepatoma; Cystic Liver Disease; Hepatic Hemangioma; Focal Nodular Hyperplasias; Hepatocellular Adenoma

Abbreviations: FNH: Focal Nodular Hyperplasia; CT: Computed Tomography; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; ICF: Informed Consent Form

Introduction

Technological advances in imaging have provided an early diagnosis of benign and malignant liver tumors. Thus, it was possible to detect liver lesions more easily, cystic, or solid. Although most cystic lesions require medical follow-up, solid lesions need to be better evaluated [1]. Liver cysts are the most common liver lesions [2]. Next, benign liver nodules occur in up to 9% of the population. The most common in descending order are Hemangioma, Focal Nodular Hyperplasia (FNH), and Hepatic Adenoma. Of these, the most worrying is an adenoma, as it has considerable complication rates [3]. These lesions are asymptomatic in most cases, and are found by Ultrasound (US), Computed Tomography (CT) or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) during the investigation of other pathologies [3]. We quickly diagnose lesions such as liver cysts and hemangiomas. However, the differential diagnosis between FNH, atypical hemangiomas and adenomas is difficult [2]. Liver cysts are congenital biliary lesions that result from the progressive dilation of biliary microhamartomas. Simple hepatic cysts occur in up to 18% in the population [1]. Most are benign, but there is a possibility of cystadenocarcinoma. The primary cystic lesions of the liver are simple cysts, hydatids, polycystic disease, cystadenoma, and cystadenocarcinoma. The ultrasound aspect has the following characteristics: anechoic lesion, without septations, smooth and sharp edges, posterior acoustic shadow, spherical, or oval shape [4,5]. USG has 90% sensitivity and specificity to detect this type of lesion [3-6]. CT shows hypodense, homogeneous, and well-defined lesion. On MRI the T1 sequence shows a hypointense lesion and the T2 course a hyperintense lesion, and there is no modification after contrast injection [7-9].

There is no specific treatment or need for periodic follow-up for an asymptomatic simple cyst. In case of cysts with malignant characteristics, irregular borders, hypoechogenicity, presence of hyperechogenic septations, wall enhancement and dorsal shadowing due to calcified areas, careful consideration should be given to malignancy, and treatment is surgical [2,3,9]. Hemangiomas occur in all age groups, being more common in adults. Most are small, asymptomatic and discovered incidentally, more prevalent in women. Although there are studies that increase hemangiomas in pregnant women or those taking oral contraceptives (COH), no direct causal link was seen in a case-control study [5]. Hemangiomas are observed in men, women without a history of COH and postmenopausal use [4]. Thus, the relationship between hormonal involvement and the development of hemangioma is not proven and is not a precondition for its development diagnosis is confirmed by CT, MRI or USG [10]. At USG, the appearance of hemangioma is of a well-defined, well-defined hyperechogenic nodule. At CT, findings include the presence of a hypoattenuating lesion in the non-contrasted phase [8]. Following intravenous administration of iodinated contrast medium, the characteristic enhancement pattern includes peripheral globular impregnation in the arterial and portal phases, progressive centripetal filling, and persistence of equilibrium enhancement [9,10]. This persistence of equilibrium impregnation helps differentiate hemangioma other hypervascular lesions such as focal nodular hyperplasia and some metastases that present faster bleaching [10,11]. In MRI hemangiomas are characterized by well-delimited lesions with pronounced persistent T2-signaling with high echo times. The gadolinium impregnation pattern is similar to the CT iodinated contrast medium impregnation. The sensitivity and specificity of MRI in the diagnosis of hemangioma reaches 98% [5-7].

Most hemangiomas do not require treatment because their complications (inflammation, coagulopathy, bleeding, compression of neighboring structures) are rare. In their approach, there is not enough scientific support to justify the suspension of COHs or contraindications to pregnancy [1,3]. FNH is found in women of reproductive age and is not related to the use of COHs. Most are asymptomatic and incidental [6,10]. FNH may be confused with adenoma, but there are already some features on abdominal CT or MRI that may differentiate them [6]. Typical CT features include well-defined lobulated lesion, hypoattenuating in the precontrast phase, and with significant homogeneous enhancement in the arterial contrast phase, with rapid washout in the portal and balance phases [1-3]. It is commonly seen a small starry central area that tends to imbibe in the late stages (central scar, composed of malformed vessels) [9-12]. In MRI, FNH presents with a slightly hypointense lesion at T1 and with slight hyperintensity at T2. The contrast pattern of UFH is similar to that described in CT [3]. When these characteristics are present, the diagnostic specificity reaches 98%, when these characteristics are not present differentiation of UFH with other lesions such as adenoma, hepatocarcinoma, and fibrolamellar carcinoma can be extremely difficult, requiring histological study [4-6]. At USG, FNH has a nonspecific pattern and difficult visualization. It is usually presented as a hypoechogenic or hyperechogenic nodule, and its definitive characterization by this method is not possible [10]. Regarding treatment, as there is no risk of bleeding or malignancy, the conduct is expectant. Surgical resection is indicated if there are symptoms, growing mass, or diagnostic doubt [1-3].

However, due to the significant number of atypical hypervascular lesions, atypical forms of benign solid lesions, hepatocarcinoma, metastases, and some types of neuroendocrine tumors, such injuries may be enhanced [12]. Concerning the hepatic parenchyma after intravenous contrast infusion, and it is not uncommon for the morphological characteristics of these lesions to overlap, which makes their diagnosis difficult. Some studies advocate the following conduct: patients with HLV of at least 1cm in diameter are safe to observe if healthy liver in patients up to 45 years old, healthy ALT/ TGP and up to 3 nodules identified on CT or MRI, because at least 81% of the lesions are benign or probably benign, with UFH and adenoma being the most common lesions in this group. For other patients with atypical lesions, the lesion biopsy is indicated and defines the treatment to be instituted [11-13]. An adenoma is an uncommon liver tumor that predominates in females (90%), aged 20-40 years. Adenomas have a high risk of bleeding, malignant transformation and are related to contraceptive use [1]. There is a dose-dependent association between estrogen and hepatic adenoma development, and the incidence of this pathology decreases with the use of modern contraceptives containing lower doses of estrogen [12]. Besides, the use of androgenic anabolic steroids for aplastic anemia or Fanconi, hereditary angioedema and improved athletic performance is also a risk factor for the development of HCA [13].

Although the diagnosis is incidental on CT or MRI, clinical manifestations are common and include mild abdominal pain located in the epigastrium, right hypochondrium, and abdominal distension [2-4]. Also, the patient may present with an acute abdomen due to adenoma rupture followed by hemoperitoneum. This complication can occur in 20-30% of cases, especially in lesions larger than 5cm [8]. An adenoma is an uncommon liver tumor that predominates in females (90%), aged 20-40 years. Adenomas have a high risk of bleeding, malignant transformation, and are related to contraceptive use [5].

There is a dose-dependent association between estrogen and hepatic adenoma development, and the incidence of this pathology decreases with the use of modern contraceptives containing lower doses of estrogen [12]. Besides, the use of androgenic anabolic steroids for aplastic anemia or Fanconi, hereditary angioedema and improved athletic performance is also a risk factor for the development of HCA [10,13]. Although the diagnosis is incidental on CT or MRI, clinical manifestations are common and include mild abdominal pain located in the epigastrium, right hypochondrium, and abdominal distension [2]. Also, the patient may present with an acute abdomen due to adenoma rupture followed by hemoperitoneum. This complication can occur in 20-30% of cases, especially in lesions larger than 5cm [8]. On MRI, the characteristics of the adenoma include hyper signal on T1 and T2 weighted images, being more discreet in the latter. The fall of the lesion signal in out-of-phase gradient-echo sequences indicates the presence of intralesional fat, as it favors the diagnosis of adenoma [6]. The paramagnetic contrast enhancement pattern is similar to that seen on CT [10].

Treatment consists of discontinuing the use of COHs as well as resection of tumors larger than 5cm [7]. Therefore, it is essential to know how to diagnose and manage such injuries to avoid medical referrals and unnecessary exams. For this, we have the epidemiology of lesions as an additional tool to corroborate the correct diagnosis. The lack of knowledge about the pathologies presented can lead to higher costs in health services as well as generating fear and anxiety in patients. Besides, knowing how to handle exposed situations avoids the risk of fatal complications.

Methods

A cross-sectional descriptive study of quantitative approach. The research took place at the Liver Study Center (LSC) of the Onofre Lopes University Hospital (HUOL), Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN) - Natal- Northeast Brazil. The LSC is contained in the Gastroenterology Outpatient Clinic, which, in turn, is part of the Digestive Unit, managed by the Care Management Division. Created in April 1995, its mission is to be the largest state referral center for liver disease. As of July 2018, there were about 13,000 registered patients in this service. The sample was chosen for convenience, and the study participants were patients with the diagnosis or initial suspicion of benign focal liver injury on imaging examination, registered at the LSC between April 1995 and July 2018. Inclusion criteria have a diagnosis or doubt of any mild focal liver injury, detected on imaging, regardless of whether or not cirrhosis is present - exclusion criteria: patients under 18 years and those who had an initial diagnosis of fatal liver injury. The data collection procedure occurred from October to November 2018 from the analysis of LSC medical records registered from April 1995 to July 2018. Knowing this, the following formula was used to calculate the sample size:

Sample size  where N = population size; e = margin

of error; z = z score (z score is the number of standard deviations

between a given ratio and the mean).

where N = population size; e = margin

of error; z = z score (z score is the number of standard deviations

between a given ratio and the mean).

The minimum sample size was used for a level of statistical significance of 95% and a margin of error of 5%. Medical records of patients with focal benign liver injury were analyzed. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 640 LSC records were selected. In the investigation of the lesions, imaging exams such as ultrasound, computed tomography, and nuclear magnetic resonance were used. In this collection, the independent variables related to the patient were gender, use of hormonal contraceptives, and the number of pregnancies. Regarding the pathology, the reason for referral to the LSC was evaluated, tests that contributed to the diagnosis of the lesion, and its final diagnosis. As a data collection instrument, a form produced through Google Forms was used, containing the following items: medical record number, gender, oral hormonal contraceptive use, number of pregnancies, the reason for referral, tests that detected the lesions, and final diagnosis. It is essential to know that the study was based on data collection in handwritten medical records. Thus, it was predicted the occurrence of measurement biases, as well as misinterpretation of data by the researchers. Besides, at certain times the collection was hampered by the lack of data records. This study was submitted to the HUOL Ethics and Research Council (HCRC) and approved under the CAAE registration: 99509218.6.0000.5292, following the consent of the institution’s head. An Informed Consent Form (ICF) was applied to the participants. Three attempts were made to contact patients with focal benign liver injury by telephone or post to obtain authorization.

Results

In the investigation of the lesions, imaging exams such as ultrasound, computed tomography, and nuclear magnetic resonance were used. Of the 640 medical records, at the end of the diagnostic investigation, 448 (70%) had a definite diagnosis, and 192 (30%) had no definitive diagnosis due to loss of follow-up (Figure 1). Patients who had a diagnosis of focal benign liver injury had in their reference card the following reasons: determination of the suggested or confirmed the mild liver injury, liver nodule to be clarified, and other gastrointestinal complaints.

Referral Reason

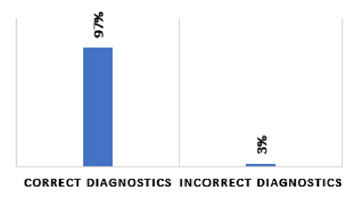

Suggested/Confirmed Diagnosis: Of the 640 medical records, it was observed that 367 patients were referred to the service with the recommended or confirmed diagnosis of liver injury. Of these, 357 (97%) patients were successfully diagnosed by the referring physicians, i.e., the diagnosis suggested by the referring physician was maintained by the NEF specialists. The other 3% had the diagnosis modified by the experts (Figure 2).

Liver Nodule to Clear Up

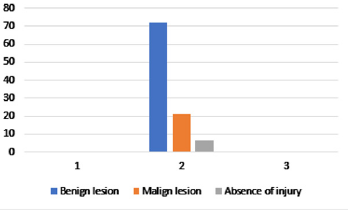

Of the 640, 253 were referred to the service with the diagnostic hypothesis of “liver nodule to be clarified.” Of these, 178 (70.35%) were not diagnosed, and 75 (29.65%) were diagnosed. Of those who were diagnosed, 54 (72%) were benign, 16 (21.33%) malignant (7 patients diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma), and 5 (6.67%) had no liver injury, as shown in (Figure 3).

Unspecific Clinical Condition

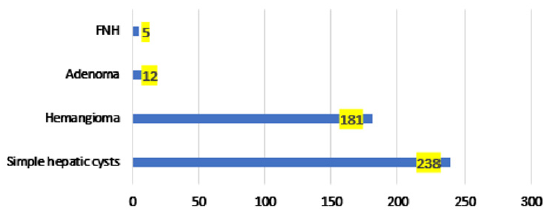

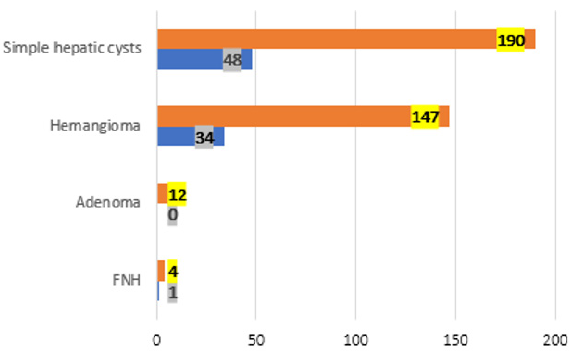

Of the 640, 20 patients were referred for another gastroenterological diagnosis, and follow-up found focal benign liver nodules in 6 patients, while 14 had suspected mild liver injury, but had no confirmed diagnosis.Prevalência das lesões hepáticas benignas focais Of all focal lesions with a definite diagnosis, the most common was the simple cyst (54.59%), followed by hemangioma (41.51%), adenoma (2.75%), and UFH (1.15%) as shown. The graph below (Figure 4). Importantly, only 9 (2.0%) patients were diagnosed with more than one focal liver injury.

Prevalence of Focal Benign Liver Lesions/Gender

There was a higher prevalence of injuries in women. Being 80.96% of injuries in women and 19.04% in men. The graph below shows the absolute frequency of injuries concerning gender (Figure 5).

Discussion

Studying benign liver lesions is relevant because they are very prevalent, with solid lesions occurring in 9% of the population1, and the simple cyst can reach up to 18% of the population [2]. Such knowledge enables the doctor to guide the benignity of this pathology as well as possible, as well as calm his patients without having to refer them or subject them to unnecessary procedures [5]. Thus, it is essential to have epidemiological knowledge about the subject as an additional tool to confirm its diagnosis6. In the present study, as found in the literature, two the simple liver cyst was the most common benign focal liver lesion [12-14]. Likewise, among the solid injuries, hemangioma was the most present in the analyzed population, what differs from the literature is the higher amount of adenoma concerning FNH [15-17]. Of the 640 patients who arrived at the NEF with focal benign liver injury, 30% did not have their diagnosis defined, i.e., which type of lesion was not clear [18]. Of the patients who were referred with liver nodules for clarification, about 29% did not have the diagnosis completed [12,19]. This is important because, among the patients who were referred for the description of a focal liver nodule and had their diagnosis completed, about 21% had the determination of a malignant lesion [10,14,20]. Thus, it is possible that patients with lesions such as hepatic adenoma, a benign lesion with the most significant potential for malignant transformation, and affecting 1:100,000 women as well as hepatocellular carcinoma, which, although rare, represent about 10% of the cases, eight may have remained without adequate clinical follow-up [12,16].

The high number of undefined diagnoses probably occurred due to the loss of follow-up of such patients due to difficulty in marking the return to service or not being able to perform the imaging exams requested by the LSC for the diagnostic conclusion, which demonstrates the weakness in the network. Outpatient and hospital care [11-13,21]. Also, the professionals who referred the patient with a suggested diagnosis had almost 100% accuracy in their suspicion. This information makes us reflect that the diagnostic methods are effective [7,8,22]. However, doctors do not have knowledge of how to manage the lesions presented, since 96.1% of the lesions that reached the LSC were simple cysts and hemangiomas, and these, in most cases, do not require regular medical follow-up [1,2,23].

It is essential to point out that the research was conducted in a tertiary health service, and the most prevalent injuries in this study could have been elucidated in primary care, reaching the most specialized polyclinics (secondary level of care according to the Unified Health System - SUS/BRAZIL). Therefore, knowing the reasons for this number of referrals to the highly complex service is vital to avoid or reduce the overcrowding of the specialized service, allowing the tertiary sector to assist in pathologies that need it [5,10]. In the patients studied, only 2% had more than one concurrent focal lesion. Thus, it is not common to present more than one focal lesion in the same individual, which reiterates the information validated in the literature [10,12]. Angiomatosis is a sporadic condition and is associated with hemangiomas on the skin and other organs. UFH can be multifocal in 10-20% of cases, and 20% of UFH coexist with hemangiomas [3,5].

Multiple adenomas are also rare [13]. Only the simple cyst is ordinary if it presents in numerous forms in more than one liver usually less than five lesions. Polycystic Liver Disease is a different pathology from multiple liver cysts and has a prevalence less than 0.1% [13,24]. Regarding prevalence by gender, women have more focal liver damage than men, regardless of type [9,25]. Unfortunately, the NEF professionals did not ask the women essential questions regarding the use of COH as well as the number of pregnancies or if they did, it was not recorded in the medical record [10,11]. With women as the main affected, these data are two crucial factors in the pathophysiology of solid liver lesions and deserve more attention, as they may modify the clinical evolution and management, for example, of those with suspected adenoma or hepatocarcinoma [4,14].

Conclusion

The study of benign liver lesions is relevant, as it allows the doctor to provide the best possible guidance on the benignity of this pathology and to calm his patients without having to refer them or subject them to unnecessary procedures. It also reinforces the importance of epidemiological knowledge on the subject, to favor diagnostic clarification and better clinical conduct. In the present study made it possible to perceive that the simple hepatic cyst is the most common focal lesion, followed by hemangioma, adenoma, and FNH. Besides, the majority of patients with these conditions are female. It is worth mentioning that the research was carried out in a tertiary health service and most of the injuries found could have been elucidated in primary health care, reaching the maximum in specialized polyclinics (secondary level), both because they are effortless and because they are prevalent in the community, for example, the simple hepatic cyst and the hemangioma. Therefore, knowing the reasons for this number of referrals to the highly complex service is essential to avoid or reduce overcrowding, giving those who need assistance in the tertiary sector. Finally, it was possible to notice that many patients were not diagnosed due to loss of follow-up. This is worrying as it is a possible sign of the ineffectiveness of the health system.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the Chief Surgeon and Full Professor, Department of Surgery, Federal University of Rio Grande Norte/Brazil, Prof. Dr. Aldo da Cunha Medeiros, for his contribution and relevance scientific discussion and the supervision of this research, acting as an expert consultant on the bibliographic survey, analysis and scientific advice. We also thank all the study components for their dedication and effort to build a scientifically validated quality study.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare by any of the authors of this study.

References

- Strauss E, Ferreira Ade S, França AV, Lyra AC, Barros FM, et al. (2015) Diagnosis and treatment of benign liver nodules: Brazilian Society of Hepatology (SBH) recommendations. Arq Gastroenterol 52 (Suppl 1): 47-54.

- Choi SH, Kwon HJ, Lee SY, Park HJ, Kim MS, et al. (2016) Focal hepatic solid lesions incidentally detected on initial ultrasonography in 542 asymptomatic patients. Abdom Radiol (NY) 41(2): 265-272.

- Hau HM, Kloss A, Wiltberger G, Jahn N, Krenzien F, et al. (2017) The challenge of liver resection in benign solid liver tumors in modern times - in which cases should surgery be done? Z Gastroenterol 55(7): 639-652.

- Marrero JA, Ahn J, Rajender Reddy K, Americal College of Gastroenterology (2014) ACG clinical guideline: the diagnosis and management of focal liver lesions. Am J Gastroenterol 109(9): 1328-1347.

- Thampy R, Elsayes KM, Menias CO, Pickhardt PJ, Kang HC, et al. (2017) Imaging features of rare mesenychmal liver tumours: beyond haemangiomas. Br J Radiol 90(1079): 20170373.

- Ronot M, Clift AK, Vilgrain V, Frilling A (2016) Functional imaging in liver tumours. J Hepatol 65(5): 1017-1030.

- Torbenson M (2018) Hepatic Adenomas: Classification, Controversies, and Consensus. Surg Pathol Clin 11(2): 351-366.

- Mu L, Chapiro J, Stringam J, Geschwind JF (2016) Interventional Oncology in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Progress Through Innovation. Cancer J 22(6): 365-372.

- Lantinga MA, Gevers TJ, Drenth JP (2013) Evaluation of hepatic cystic lesions. World J Gastroenterol 19(23): 3543-3554.

- Renzulli M, Clemente A, Tovoli F, Cappabianca S, Bolondi L, et al. (2019) Hepatocellular adenoma: An unsolved diagnostic enigma. World J Gastroenterol 25(20): 2442-2449.

- Ponnatapura J, Kielar A, Burke LMB, Lockhart ME, Abualruz AR, et al. (2019) Hepatic complications of oral contraceptive pills and estrogen on MRI: Controversies and update-Adenoma and beyond. Magn Reson Imaging 60: 110-121.

- Amico EC, Alves JR, Souza DLB, Salviano FAM, João SA, et al. (2017) Hypervascular liver lesions in radiologically normal liver. Arq Bras Cir Dig 30(1): 21-26.

- Agrawal S, Agarwal S, Arnason T, Saini S, Belghiti J (2015) Management of Hepatocellular Adenoma: Recent Advances. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 13(7): 1221-1230.

- Chiche L, Adam JP (2013) Diagnosis and management of benign liver tumors. Semin Liver Dis 33(3): 236-247.

- Bröker ME, Ijzermans JN, Van Aalten SM, De Man RA, Terkivatan T (2012) The management of pregnancy in women with hepatocellular adenoma: a plea for na individualized approach. Int J Hepatol 2012: 725735.

- Hartke J, Johnson M, Ghabril M (2017) The diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Diagn Pathol 34(2): 153-159.

- De Knegt RJ, Potthoff A, Wirth T (2020) [Management of benign liver tumors]. Der Internist.

- Srinivasa S, Lee WG, Aldameh A, Koea JB (2015) Spontaneous hepatic haemorrhage: a review of pathogenesis, aetiology and treatment. HPB (Oxford) 17(10): 872-880.

- Colombo M (2015) Diagnosis of liver nodules within and outside screening programs. Ann Hepatol 14(3): 304-309.

- Belghiti J, Cauchy F, Paradis V, Vilgrain V (2014) Diagnosis and management of solid benign liver lesions. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 11(12): 737-749.

- Venkatesh SK, Chandan V, Roberts LR (2014) Liver masses: a clinical, radiologic, and pathologic perspective. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 12(9): 1414-1429.

- Buell JF, Tranchart H, Cannon R, Dagher I (2010) Management of benign hepatic tumors. Surg Clin North Am 90(4): 719-735.

- Zarzour JG, Porter KK, Tchelepi H, Robbin ML (2018) Contrast-enhanced ultrasound of benign liver lesions. Abdom Radiol (NY) 43(4): 848-860.

- Roncalli M, Sciarra A, Tommaso LD (2016) Benign hepatocellular nodules of healthy liver: focal nodular hyperplasia and hepatocellular adenoma. Clin Mol Hepatol 22(2): 199-211.

- Abdelrahman K, Schmidt S, Sciarra A, Sempoux C (2017) Benign focal liver lesions: a clinical, radiological and pathological review. Rev Med Suisse 13(572): 1474-1479.

Research Article

Research Article