Abstract

Adapting to the ageing population is one of the biggest challenges for 21st-century cities. This research was focused on the thermal and acoustic comfort perception of older adults in two outdoor public spaces in the city of Newcastle Upon Tyne in the United Kingdom, through a mixed methodology including environmental measurements and questionnaire surveys to 73 people over 60 years old during the autumn of 2019. Results about thermal comfort showed that the range of the temperature where at least 80% of the older people felt the environment acceptable, was between 11.27 and 19.93 C°. While concerning acoustic comfort, although measured sound levels exceed the limits considered harmful to health (> 65 dB) 86.3% of the interviewees perceived the level of sound as ¨Pleasant¨ and 83.6% were not annoyed. Decreased thermal and auditory sensitivity makes older people vulnerable to climate and noise effects on health. It is important to consider those findings to achieve healthier spaces adapted to the needs of older adults, which encourage greater use and participation and improve their quality of life.

Keywords: Outdoor Thermal Comfort; Acoustic Comfort; Older Adults; Age Friendly Cities; Healthy Ageing

Short Communication

Newcastle Upon Tyne is a city in the North East of England, in the metropolitan district of Tyne and Wear. Its climate is humid temperate oceanic (Cfb) according to the Köppen climate classification. The average annual temperature is 8.5 °C, with an average rainfall of 655 mm. It is the eighth-most populous city in England with 314 366 inhabitants, from them, 19.4% are people over 60 years old [1] and it is estimated to be 44.2% for 2039 [2]. International policies have been developed to adapt cities to demographic change, such as the “Global Network for Age-friendly Cities and Communities “ of which Newcastle is part. These cities must recognize the diversity of the elderly population, and facilitate an active, healthy, satisfying aging and promote inclusion. Some authors have found that outdoor public spaces influence people´s mental and physical health and some recognize thermal comfort as one of the factors that most influence the use of these spaces, followed by acoustic comfort among others [3]. There is still little research in the field of thermal and acoustic comfort for older adults, it has been usually focused on the characteristics of the ¨average young person¨ without considering the physiological, physical and psychological differences that characterize the elderly.

Climate-related diseases produce more than 150000 deaths each year, where children and the elderly are the most vulnerable groups [4]. Some authors found that thermal sensitivity, response and adaptation is affected with age [5], and climatic extremes increase the risk of the elderly to have pneumonia, cardiac arrest, dehydration, hypothermia and hyperthermia [6-8]. In England and Wales, it is estimated that there was an excess of 51100 deaths in the last winter, attributable to the cold, of which 92% were people over 65 [9]. While the future scenario will change, it includes heat waves above 30 °C and it is estimated that there will be an increase between 700 and 1000 more deaths per year related to heat in England [10]. On the other hand, traditionally, noise was related to health disorders at workplaces only, but now it is recognized as a form of pollution that affects people’s health and well-being, [11] which is constantly increasing in conjunction with the urbanization of cities, population growth and vehicular flow, since human activities are the main sources of noise pollution. The effects of noise on health have been demonstrated [12,13]; Besides, noise pollution can intensify some frequent illness in older people like dementia, depression [14].

Materials and methods

This research was developed through a mixed methodology that includes measurements of environmental parameters (air temperature, relative humidity, wind speed, sound levels), observations and questionnaire surveys. Fieldwork was developed between September and November of 2019, in two outdoor spaces of Newcastle City centre: Northumberland Street and Old Eldon Square, at three different points within each public space, for 15 minutes each, twice a day between 10:00 am and 4:00 pm, as these were the hours of greatest occupation. To measure the sound level a sound level meter (PCE-322) was used, with a frequency of 31.5- 8 Hz, a range of 30-130 dB and accuracy of ±1.4 db. For humidity and temperature, a HOBO UX100 data-logger thermometer was used, with an accuracy of ±0.21 °C temperature and ±2.5% relative humidity. While a digital anemometer Prostar MS6252A was used for wind speed. Finally, Sky View Factor (SVF) has been calculated using fisheye photographs (180°) and Rayman 1.2 software.

The questionnaire survey [15] had two parts, the firs was about personal information (age, gender, frequency of visit, level of clothing isolation, and others) and the second part was about their thermal sensation (Linkert scale of 7 points) [16], thermal preference (McIntyre scale of 3 points) [17] and acoustic perception.

Results and discussion

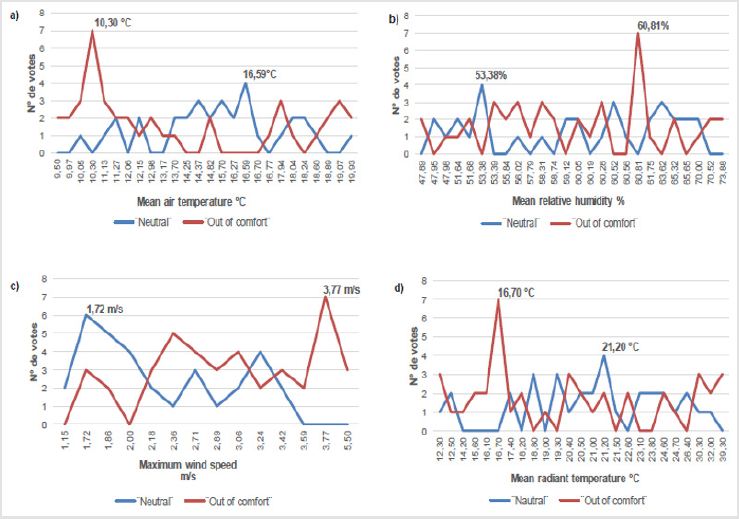

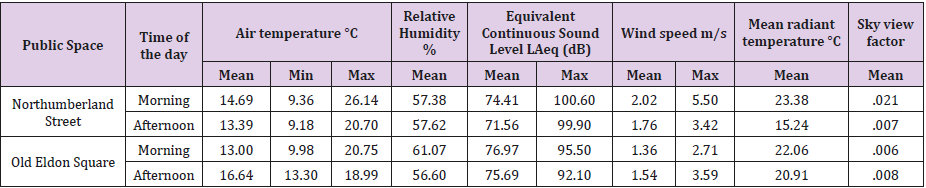

Table 1 is a summary the environmental measurements on fieldwork, where 73 people between 69 and 90 years old were interviewed between September and November 2019, from them 53% are men. About their frequency of visit, 65% visit those spaces several times a week and 21% daily, about 80% of them perform passive activities (sitting, resting, reading, eating) and only 20% of them do some physical activities like walking, being the men the most active and the ones that stay longer on site. The temperature range where 80% of the interviewees felt the environment as acceptable (not cold or hot) [16] was found between 11.27°C and 19.93°C. In this case, the highest percentage of people feel “neutral” in terms of their thermal sensation has coincided with the highest percentage of people who say “they would not change” in terms of their thermal preference at a mean temperature of 16.59 °C (neutral temperature and preferred temperature); at a mean relative humidity of 53.38%; with a mean radiant temperature of 21.20 °C and a maximum wind speed of 1.72 m/s. In addition, it can be seen that the highest percentage of people out of comfort (slightly cold to cold) and that it also coincides with people who would like to be “warmer” is given at a temperature of 10.30 °C, relative humidity of 60.81%, maximum wind speed of 3.77 m/s and a mean radiant temperature of 16.70 °C (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Percentage votes “neutral” in relation to

a. Mean air temperature;

b. Mean relative humidity;

c. Maximum wind speed and

d. Mean radiant temperature

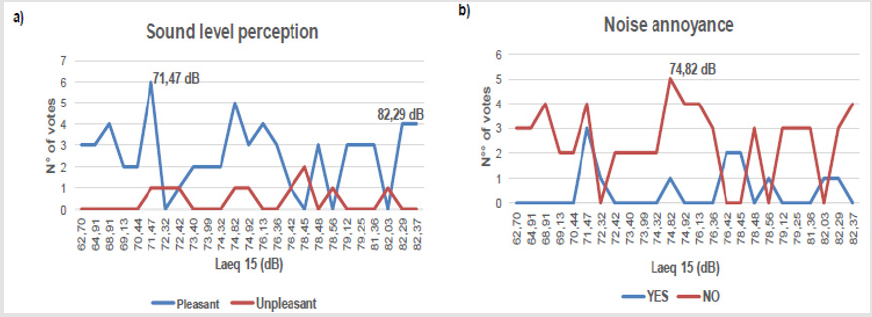

About acoustic comfort, 86.3% of the interviewed found the sound level as pleasant and 83% were not annoyed by noise, although those levels were usually over 65 dB which is the limit considered harmful for health and allowed in residential zones in Europe[18] (Figure 2) some studies found similar results and attributed to age-related changes in auditory perception [19,20] and other authors suggest that a listener´s expectations for a certain type of sound to be present in a particular place decreases their annoyance [21,22]. About soundscape perception, the most pleasant sounds for the older people in those spaces were birds singing (18%) and music (35.6%) (street singers) and the most unpleasant sounds for them were busses (28.7%) in Old Eldon Square and shoots of sellers (9.6%) on Northumberland street. It is interesting to note that some sounds like music could be pleasant for some people but unpleasant for others.

Figure 2: Percentage votes “neutral” in relation to

(a) Sound level perception and

(b) Noise annoyance in relation to Equivalent Continuous Sound Level Lea (dB).

Conclusion

Decreased thermal and auditory sensitivity makes older people vulnerable to microclimate and noise effects on health. It is important to consider those findings and further studies are needed to achieve healthier spaces adapted to the needs of older adults, which encourage greater use and participation and improve their quality of life.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the Ecuadorian Institute of the Secretariat of Higher Education, Science, Technology and Innovation of the Government of Ecuador (SENESCYT) under Grant [109-2017 (SENESCYT-SDFC-DSEFC-2017-4040-O)].

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest exists in the submission of this manuscript, it has been approved by all authors.

References

- (2019) World Health Organization. No Title. Age friendly Word. Newcastle upon Tyne.

- (2019) New castle City Council. Newcastle City Council. Equal. Stat. Res. Inf.

- Lai D, Zhou C, Huang J, Jiang Y (2014) Outdoor space quality : A field study in an urban residential community in central China. Energy Build 68:713-720.

- (2005) World Health Organization. Climate change and human health . Clim Heal.

- Baquero Larriva MT, Higueras García E (2019) Confort térmico de adultos mayores: una revisión sistemática de la literatura cientí Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol 54(5): 280-295.

- Novieto DT, Zhang Y (2010) Thermal comfort implications of the aging effect on metabolism cardiac output and body weight. Adapt to Chang New Think Comfor.

- Van Hoof J, Hensen JLM (2006) Thermal comfort and older adults. Gerontechnology 4(4): 223-228.

- Van Hoof J, Schellen L, Soebarto V, Wong JKW, Kazak JK, et al. (2017) Ten questions concerning thermal comfort and ageing. Build Environ J 120: 123-133.

- (2019) Age UK. Later Life in the United Kingdom.

- (2019) Department for Business E& IS. Climate change agreements . Clim Chang Explain.

- Herranz Pascual K, Garcia I (2017) Confort Acústico Frente a Molestia Por Ruido: Diferentes Casuísticas En Un Entorno Urbano in: Sociedad Española de Acústica editor 48o Congr Español Acústica Encuentro Ibérico Acústica Eur Symp Underw Acoust Appl Eur Symp Sustain Build Acoust. A Coruña 354-361.

- Schnell I, Dor L, Tirosh E (2016) The effects of selected urban environments on the autonomic balance in the Elderly A pilot study. Studies 3(5): 4903-4909.

- Van Kempen EEMM, Kruize H, Boshuizen HC, Ameling CB, Staatsen BAM, et al. (2002) The Association between Noise Exposure and Blood Pressure and Ischemic Heart Disease: A Meta analysis. Environ Health Prospect 110(3): 307-317.

- Goines L, Hagler L (2007) Noise Pollution: A modern plague. South Med J [Internet] 100(3): 287-294.

- Baquero MT, Higueras E (2019) Factors Ambien tales Que Influyen En El Uso Del Espacio Público Para Las Personas Mayores En Madrid. Rev Urbano 40: 108-126.

- (1966) ASHRAE. Thermal Comfort Conditions. ASHRAE Standard 55-1966. Atlanta.

- Salata F, Golasi I, De Lieto Vollaro R, De Lieto Vollaro A (2016) Outdoor thermal comfort in the Mediterranean area. A transversal study in Rome, Italy Build Environ 96: 46-61.

- (2002) European Parlament and Council. Directive 2002/49/EC relating to the assessment and management of environmental noise. Brussels.

- Miedema HME, Vos H (1999) Demographic and attitudinal factors that modify annoyance from transportation noise. J Acoust Soc Am 105(6): 3336-3344.

- Yu L, Kang J (2008) Effects of social, demographical and behavioral factors on the sound level evaluation in urban open spaces. J Acoust Soc Am 123: 772-783.

- Bruce NS, Davies WJ (2014) The effects of expectation on the perception of soundscapes. Appl Acoust 85: 1-11.

- Ge J, Hokao K (2005) Applying the methods of image evaluation and spatial analysis to study the sound environment of urban street areas. J Environ Psychol 25(4): 455-466.

Short Communication

Short Communication