Abstract

Background: The aim of this study is to assess the prevalence of picky eating among preschoolers and to address the clinical link between eating behavior and growth, physical activity, development, and health status.

Methods: In this study, a structured questionnaire was used to perform a crosssectional descriptive study of 800 parents of preschoolers aged 2-4 years in Kurdistan/ Iraq. Data collected included: demographics, food preferences, eating behavior, body weight, BMI, height, development, physical activity, and records of medical illness. Data from children defined as picky or non-picky eaters responses were analyzed and compared using standard statistical tests according to questionnaire records obtained from participating parents.

Results: The mean age of the children was 2.85 years; among eight hundreds participants, 620 (77%) were picky eaters. Compared with non-picky eaters 180 (23%), z-score of weight-for-age, height-for-age, and body mass index (BMI)-for-age in picky eaters was 0.90, 0.71, and 0.42 SD lower, respectively. There were significant variations of rates in the weight-for-age, height-for-age, and BMI-for-age percentiles <15, between picky and non-picky eaters (P = 0.04, 0.023, and 0.005, respectively). Certain findings were higher in picky as compared to non-picky preschoolers including negative social communication such as afraid of unfamiliar places 65% vs 13.3%, afraid of being lonely 14.6% vs 12.1%, poor physical activity 36.8% vs 17.7%, learning disability 16.2% vs 7%, attention deficit 11.8% vs 4.3%, speech delay 4.6% vs 3.3%, respectively).

Conclusion: The prevalence of picky eaters in preschool children was high, resulting in significant negative impacts on growth, nutritional status, development, physical activity, and health status.

Keywords: Picky Eating; Preschoolers; Growth and Development; Physical Activity; Health Status

Introduction

\Picky or selective eating often refers to those children with strong food preferences, consuming an insufficient variety of foods, restricting the intake of certain food groups, consuming a limited amount of food, or being reluctant to try new foods. Picky-eating behaviors are common during infancy and childhood [1]; though, till now the term picky eater is not well understood [2-4]. The prevalence of selective eating among children varies in different countries. In a study conducted in USA, almost fifty percent of young children were reported by their parents not to be eating optimally [5]. Another study of 120 children aged 2-11 years identified thirty nine percent as picky eaters [6], and picky eating prevalence as high as fifty percent was reported in children aged 19-24 months in a study carried out in North America [7]. Among children aged three to seven years old in China, fifty four percent was reported by parents to be picky eaters [8]. A recent study reported that thirty six percent of young Chinese preschoolers aged 2-3 years old had selective-eating behaviors [9].

Moreover, contradictory outcomes of prevalence of childhood

picky eaters were reported studies, probably due to variations

in definitions, methods of assessment, and diverse age ranges of

children studied (Goh, Jacob, 2012, Jacobi et al, 2008, Mascola et al,

2010, Micali et al, 2011) [1,6,10,11]. Preschoolers often use their

body language or non-linguistic verbalizations to express their

meal favors, while older children independently make their food

preferences at school, therefore the parent understand the refusal

of food as being stronger as the child grows. However, picky eating

behaviour is quite frequent in school children with the prevalence

ranging from thirteen percent-forty seven percent in developed

countries (Goh. Jacob, 2012, Jacobi et al, 2008, Mascola et al, 2010)

[1,6,10]. Picky eaters usually have a limited dietary variety and

consume few fruits, vegetables and meat rich in micronutrients

[12]. In addition, their intake of fats, fiber, protein and sweets is

lower than that of non-picky eaters [2]. It is still unclear whether

the impact of picky eating on height and weight depends on the

types of food rejected by the picky eaters.

Picky eaters might have normal development besides to those

with medical or developmental disorders [5], and selective eating

in early childhood might extend and proceed to eating disorders in

adolescence and early adulthood [13]. Also, there might be a link

between behavioral feeding disorders and delayed development

in children, and few picky eaters’ children might have low weight

[3,8,14,15]. In addition, fussy eaters have certain distinguished

characteristics reluctance to try new foods, a dislike of certain

varieties of foods, and a very good opinions about food preparation

[1,2,12], which result in eating small quantities and a limited types

of food, potentially impacting a child’s growth (Goncalves 2013)

[9,16]. Consequently, this can result in long-term eating disorders

in adolescence and early adulthood. Hence, childhood picky eating

have reported conflicting results, possibly due to inconsistencies

in definitions and methods of assessment, as well as different

age ranges of children studied. (Needham 2007) [17]. Prevalence,

studies [1,6,10,11].

Some picky eating behavior in very young children, from

parents’ subjective perceptions, may be due to Neophobia, which is

different from pickiness in older children. Neophobia is the phobia

or fear of trying anything new in particular continuous and unusual

fear. In its milder form, the child dislike to try unusual things that

seem to him to be new or unfamiliar. In the context of children the

term is generally used to indicate a tendency to reject strange foods.

High nutrient requirement is needed for school-aged children as

they undergo rapid growing ; therefore, their eating habits are

essential for optimal development. However, picky eating behavior

is relatively common during childhood while at school, with the

prevalence ranging from thirteen percent to forty seven percent

in developed countries [1,6,10]. Moreover, selective eating in early

childhood has been shown to continue into mid-adolescence, which

is associated with eating disorders, lasting fussy eating, and limited

dietary variety in adolescence and adulthood [18-20].

However, the clinical impact of picky eating on the growth of

children is still controversy. One longitudinal study of 1498 children

aged 2.5, 3.5, and 4.5 years in Québec found that picky eaters were

twice as likely to be underweight at 4.5 years old than children who

were never picky eaters [21], whereas, Contradictory findings from

another longitudinal study with 120 children in the San Francisco

Bay area followed from 2 to 11 years of age suggested no significant

effects of picky eating behavior on growth [6]. These opposite

results might be due to certain reasons: 1st, the differences in perceptions

and assessments of picky eating, 2nd, failure to adjust various

confounding factors including age, gender, birth weight of the

child, and socio-demographics. Cognition and intellectual status of

school children is very relevant and is often concerning for parents.

Certain studies indicated that nutrition during early childhood had

long-lasting impacts on the intelligence of children [22,23].

As the brain grows and develops faster than the rest of the body,

nutrient deficiency, especially protein, iodine, iron, zinc, folic acid,

and vitamin B 12, at a critical stage of development may result in

everlasting changes in brain structure and cognition status [22].

In comparison to non-picky eaters, selective eaters usually have

a restricted dietary variety and limited consumption of few fruits,

vegetables, and meat rich in micronutrients [15]. Moreover, their

intake of fats, fibre, protein and sweets is lower than that of nonpicky

eaters [2]. It is unclear whether the impact of picky eating on

height and weight depends on the variety of food rejected by the

picky eaters. However, in one study a lower intake of vitamin E and

C, and fibre was found in picky nine-year-old girls [2].

Subjects and Methods

This is a cross-sectional descriptive study used a structured questionnaire to obtain information from parents in Iraq/Kurdistan region who were parents to children aged 2-4 years. Participants were randomly selected from Zakho General Hospital-Department of Pediatrics, Nutrition Rehabilitation Center(NRC) as well as private clinic for general pediatrics, child’s nutrition and growth in Zakho-Duhok city in Iraq to meet pre-specified allocations for race, age, and gender, representative of the national population. A total of 800 participants (400 from each place) who met the eligibility criteria were enrolled and included in this study. Consent forms were obtained from each preschoolers’ parents or caregivers to address their participation in this research study.

Interview Process

The interviews were scheduled, managed and enrolled by the authors themselves. Children aged 2-4 years old who had history of chronic illnesses, that might negatively impact their food behavior, were excluded including prematurity, low birth weight (<2,500 g), dental diseases, organic diseases, mental disorders such as cerebral palsy, genetic diseases, psychiatric illness, anorexia, gastro-esophageal reflux disease, food allergies, and lactose intolerance. As well as those preschoolers with acute illness such as flu or diarrhea were all excluded. Data for this study were collected between September 2018 and July 2019. All participants gave their written and informed consent signed by their parents. Using a multi-stage stratified cluster sampling method, 800 children aged 2-4 years were recruited. Data collection were obtained in this study through face-toface interviews with the children’s parents. The participants were all eligible to share in this study. Also, parents with limited economic means to support their children’s nutrition, had inadequate idea or knowledge for children’s diets, development, and physical activities, or were unable to provide sufficient healthy diet for other reasons, were not included in this study.

Socio-Demographics and Anthropometric Measurements

The authors, after confirming eligibility, contacted families and

arranged a meeting with parents for a face-to-face interview. The

socio-demographic information was collected from the parents

with a structured questionnaire survey (mothers: 99% of parents)

and was administered by trained interviewers. Demographic data

included child’s date of birth, gender, ethnicity, and birth weight.

As well as Data including any medical history of child’s food allergy

history and parents’ body weight and height were also considered

from the interview. During interview process we asked parents

what they do children prefer to eat, how do the children act when

they eat, their growth and development, physical activity, general

health questionnaire. The interviews took approximately half an

hour to complete.

Special forms for parents were used to collect information about

the family size and the education level to get socio-demographic

data using questionnaires. Closed-ended categorical questions

including lists of options for parents to choose, to get information

about the nutrition and general medical health status of the included

participants. The main questions included diets preferences, eating

behaviour, parent/child communication during mealtimes, speech

ability, developmental behaviors, day activities, and records of

chronic diseases in the last 12 months. A quantitative study with no

detailed discussions were conducted in this research. The author

carried out the interviews between the 1st of April and the 31of

June 2019. All parents of children introduced their agreement and

signed a consent form for their children to participate in this study.

Growth and Nutritional Assessment of Preschoolers

Children’s weight and height were measured in Zakho General Hospital-Nutrition Rehabilitation Center-Department of pediatrics on an individual and solicited basis, before the interview associated with the food frequency questionnaire. Children were weighed without shoes and wore napkins only for accuracy purposes to get body mass index (BMI) [weight (kg)/height (m2)]. The percentile and z-score of weight-for-age, height-for-age, and BMI-for-age were considered to assess the impact of picky eating behavior on children’s growth and nutrition status. Weight-for-age, weightfor- height, and height-for-age were expressed as sex and age agespecific percentiles, and the growth standards for height, weight, and BMI based on a general WHO population were used to obtain z-scores for each measurement according to age and sex [24]. The used parameters to assess growth status were height-for-age and weight-for-age z-scores, and those used to evaluate nutritional status were weight-for-age and BMI-for-age z-scores. Weightfor- age, height-for-age, and BMI-for-age percentiles <15 were considered to indicate that the child was underweight, of short stature, or suffering from malnutrition, correspondingly.

Assessment of Picky Eating

To evaluate picky eating behavior through organized questionnaire tow categories were addressed in this study. 1st is the food preferences and 2nd is the eating behavior.

Food Preferences: In an organized questionnaire, all parents were questioned about their child’s food preferences. Questions about preferences for food and food variety included a modified version of a questionnaire based on the United Kingdom Department of Health Survey of the Diets of British School Children [24] and dietary assessment among school-aged children [18]. Also, changes were made to the questionnaire used and based on Iraqi-Kurdistan dietary culture and food habits.

The questionnaire included 2 main items:

Child’s Meals and their Preferences in more than Ten Food Categories

(i) Grains (rice, bread, cereals, potato, noodles, pasta, etc.),

(ii) Protein foods (eggs, red or white meat, fresh fish, seafood,

beans, potato, etc.)

(iii) Vegetables,

(iv) Fruits,

(v) Dairy products (milk, cheese, yogurt, etc.),

(vi) Fats and oils (vegetable oil, butter, cream, salad, etc.), and

(vii) Snacks and sweets (chips, candy, cookie, cake, etc.) in past

15 days.

Preferences in Common Foods (list of Fifty Foods for Regular Meals): The responses were had and did not have ” in each food and responding to preferences of the tried foods. Items were scored on a five-point scale as “love and enjoy it very much,” “love it moderately,” “Dislike it moderately,” and “Dislike it very much.”

Feeding and Eating Behaviors

On the other hand, another questionnaire arranged for parents to find out about their feeding behaviors (10 items: six appropriate behaviors, four inappropriate behaviors) and their child’s eating behaviors (ten items: 4 healthy eating behaviors, six picky eating behaviors). The eating behavior questionnaires were inspired from the Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire developed by Wardle et al. the classification of feeding disorders of infancy and early childhood by Chatoor and Ammaniti [13] and a study about the trends of eating behaviors in preschool children [25,26].

The four questions for picky eating behaviors included

(i) Eats limited foods

(ii) Reluctance to eat usual meals,

(iii) Refusal to try new meals, and

(iv) Refusal of one or multiple food groups in six major food

groups (grains, protein foods, vegetables, fruits, dairy foods,

and fats and oil).

Items were scored on a five-point scale as “not at all,” “seldom,”

“on occasion,” “frequently,” or “always.” Mean scores were calculated

for each subscale (range 1-5) with higher scores indicating higher

values of each trait.

Accordingly, a defined picky eating behavior was derived in

case of positive response of “always” to at least one item of the

picky eating behaviors on questionnaire of eating behaviors in this

research study.

Assessment of Development

The questionnaire for assessment of development was modified based on the Denver Developmental Screening Test II. The test assesses children from 2 to 4 years old who are apparently asymptomatic . The DDST-II consists of 125 items grouped into four areas: personal-social, fine motor, gross motor and language. Additionally, each recording sheet includes a behavioral test in which several items are recorded, such as the child’s interests or capacity to pay attention, among other items. Upon completion of the test, three scores or classifications are possible: normal, suspect and not testable. The DDST-II has been adapted and emphasized in Singapore, Iran and Sri Lanka. The Sensitivity and specificity values in Spanish version of the test were 89 and 92 %, respectively; and more reliable in Hallioglu et al. study found sensitivity values of 100 % and specificity of 95 percent. DDST II for early identification of the infants who will develop major deficit as a sequel of hypoxicischemic encephalopathy.

Assessment of Physical Activity

A modified questionnaire for assessment of physical activity was used based on a study of objective measurement of physical activity and sedentary behavior [23]. Statements relating to physical activity requested respondents to rate their degree of agreement on a five-point scale (unacceptable, improvement expected, acceptable, exceeding expected, outstanding). Mean scores were calculated for each subscale (range 1-5) with higher scores indicating higher values of each trait. The questionnaire assessing physical activity consisted of four items: normal-pace walking; sport activities; stair-climbing; and running. The answers of “unacceptable” or “improvement expected” of the item assessed were considered as having low level physical activity. Those with two or more low-level physical activities were defined as having a poor general physical activity level.

Results and Findings

Data and Characteristics

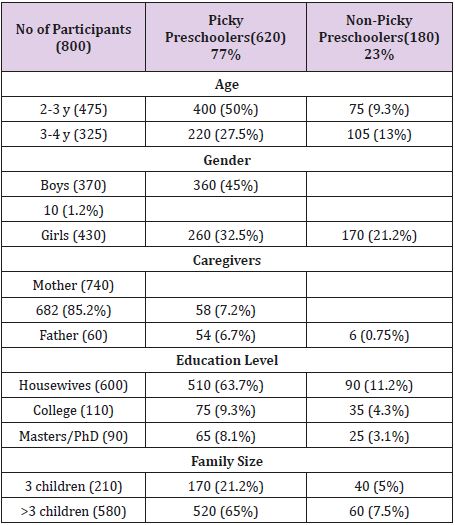

In this cross-sectional study, eight hundred preschoolers aged 2-4 years were screened, of whom 740 met eligibility criteria were enrolled. Sixty participants were excluded, 30 preschoolers had chronic illnesses affecting eating habits and growth status, 15 caregivers had limited economic means to support their children’s diets, and caregivers did not have enough concept for children’s nutrition support, development, and physical activities or were unable to provide adequate nutrition for other reasons. Table 1 illustrates the demographic variations between picky and nonpicky eaters. Based on the food and dietary questionnaire survey, 620 preschoolers (77%) were found to have picky-eating behavior. The mean age of these children was 2.97 ± 0.59 years. Certain factors such as gender, age, primary caregiver, education levels of caregiver, or family size between the participants have no statistical variations in this study (Table 1). In this study, {always} responders among picky preschoolers cohort were commonly as follows: Eating sweets or snacks instead of meals(52.6%), Refusing food, particularly fruits and vegetables (37.8%), Reluctant to eat regular meals (27.6%), Do not like to try new food (Neophobia, 23.3%), Ingestion of specific kinds of food (16%), Excessive drinking of milk (14.2%). Seventy-eight cases among preschoolers disliked meat (9.7%), vegetables(180 cases, 22.8%), fruit(62 cases, 7.7%), and certain types of fruit or vegetables (52%, 220 cases).

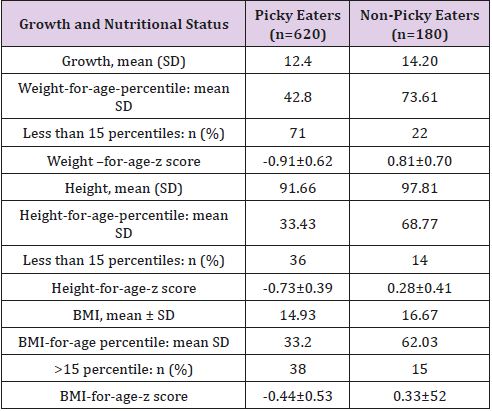

Anthropometric Data

As shown in Table 2 below, in this study in Iraq/Kurdistan region, for preschoolers, the standard weight, height, and BMI(Body Mass Index) were 12.4 kg, 91.66 cm, and 14.93, correspondingly. In comparison to non-picky eaters, such results for picky eaters were interestingly low. As well as picky eaters had significantly lower average weight-for-age, height-for-age, and BMI-for-age percentiles; Besides, less than fifty was the mean weight- and height-for-age percentiles in picky eaters, while it was greater than fifty (median of population) in non-picky eaters. Picky preschoolers also stated that they had, compared to non-picky eaters, higher rates of weight-for-age, height-for-age, and BMI-for-age percentiles less than fifteen. Considerably greater percentages of children with a weight-for-age percentile less than 15, a height-for-age percentile <15, and a BMI-for-age percentile <15 were picky eaters respectively, (Table 2). The same scenario was with the z-scores, as the average z-scores of weight-for-age, height-for-age, and BMI-forage in picky eaters were all obviously less than those z-scores of non-picky eaters (Table 2).

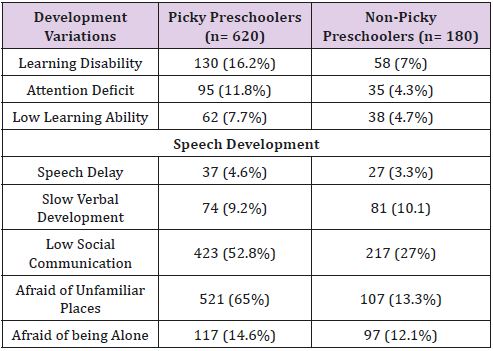

Development

Table 3 displays differences in the development between picky eaters and non-picky eaters. Attention deficit and low learning ability were the detected low-quality developments in learning ability. Slow verbal development and poor language development were the detected low-quality developments in verbal ability. Afraid of unfamiliar places and afraid of being alone were the detected low-quality developments in interpersonal relationships. Table 3 below demonstrates the prevalence rate of three categorized low-quality developments in picky and non-picky group children. Of the three categories of low-quality development, a significantly higher prevalence of children who had negative interpersonal relationships was found in the picky group. A higher rate of “afraid of unfamiliar places” was reported to be picky eaters (Table 3). Compared to non-picky group, a significantly lower score of all questionnaire items was found in the picky group (26.6 ± 3.1, vs. 20.8 ± 2.8) (Tables 3 & 4).

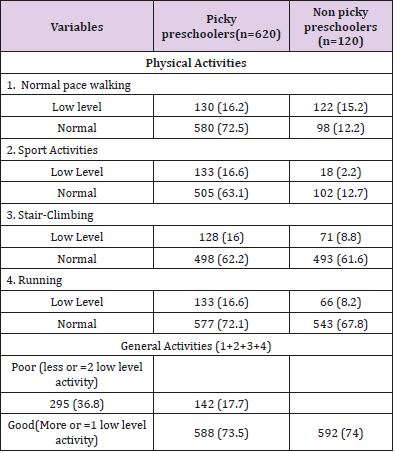

Table 4: Presentation levels of physical activities and health status among picky and non-picky preschoolers.

Discussion

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP),in addition to many world-wide institutions, stated that ,the importance of early detection of psychomotor delay in preschoolers, can be achieved by repeated systematic screening at ages of 9, 18 and 30 months consequently. Therefore, a reliable test to adapt for addressing behavioral and motor development in preschool children is essential. The widely used screening tests is the Denver Developmental Screening Test (DDST) which was first published in 1967. Despite of several studies have illustrated the prevalence of picky eaters among preschoolers, a small number have evaluated the correlation of picky eating with pediatric development, physical activity, and health status. In this study we provide an interesting impression of selective preschoolers aged 2-4 years in Iraq/ Kurdistan region and consider remarkable thoughts regarding the impact on children’s growth, development, physical activity, and disease load. The food preferences, development, and physical activities between picky eaters and non-picky eaters were scored and analyzed statistically. Our study is the first in Iraq to correlate the behaviors of preschoolers with low-quality development and lower performance values of physical activities.

The definition of picky eaters among children is variable. Lots

of studies are available regarding to the prevalence of picky eating

in childhood with a huge difference was shown [19]. The majority

of previous studies use parental views concerning picky children

to recognize child’s selective eating. The core of definition of picky

eating was based on the objective questionnaires of detecting picky

eating, was used in our study, by strong existence of picky eating

behaviors on four queries. As compared to already published papers,

the prevalence of picky behaviors among preschoolers, was

higher, at fifty seven percent [6,7,11]. A new report indicated three

significant parent-reported feeding questions that may identify

persistent picky eaters at an early age [20]. Therefore, based on

parental views, the three questions included a subjective identification

of picky eater by parental thoughts, and two typical and

ordinary picky eating behaviors (strong likes concerning food and

unwillingness to accept new foods). These two picky eating behaviors

were adopted in our questionnaire. We recruited the other two

characteristic fussy eating behaviors which could assist to spot remarkable

precision of picky eating behaviors among preschoolers.

In Hong Kong, a large longitudinal study revealed that forty

three percent among seven thousands children aged 2-7 years, were

reported by their parents as being picky eaters, and forty percent of

children’s picky-eating behavior lasted longer than 2 years [6,11]. A

cross-sectional survey showed that the percentage of picky eaters

increased from nineteen percent at 16 weeks old to fifty percent

by age of 2 years [7]. In addition, another cross-sectional survey

of Chinese preschoolers addressed that prevalence of picky eating

was thirty six percent in 2-3 years olds as compared to twelve

percent in 6-11-month-old ([8]. Therefore, such results indicate

that picky eating is a persistent dilemma [6,7]. In our current study,

correlatively more participants in the younger age group were

picky eaters (50% age 2-3 years vs. 27.5% age 3-4 years). However,

pickiness behavior start to decline with age through early childhood

and reach its peak time ate age of two-four years old according

to previous studies [4,12]. The picky eaters in this group of

preschoolers from Kurdistan/Iraq illustrated vital lower numbers

and values of accepted foods and food preference respectively. The

questionnaire items for the evaluation of pickiness behavior in

the current research study was similar to those questionnaires of

preceding studies [7,16,17].

Therefore, meat, fruit, fish, and specific kinds of vegetables

were the food items that they dislike to consume; parallel pickyeating

behaviors were observed among children in Hong Kong [11].

the most common picky-eating behaviors among preschoolers in

Iraq/Kurdistan region were being unwilling to eat regular meals,

refusing fruit and vegetables, and being likely to eat sweets or

snacks instead of meals. Such results are identical to picky-eating

behaviors conducted in another research study in Singapore [16].

Further research studies revealed that picky eaters were twice as

likely to be underweight at 4.5 years old as non-picky eaters [26].

In the current study, excessive milk-drinking, eating sweets and

snacks were common picky-eating behaviors. In preschoolers and

according to the food records, extreme milk-drinking may result

in low appetite at mealtimes and cause inadequate energy intake.

According to cross-sectional analysis in the United Kingdom and

based on questionnaires completed by parents when their children

were aged 30 months, revealed that seventeen percent eating a

partial quality, thirteen percent preferring drinks to food: therefore,

limited variety and favoring drinks were the most common problem

behaviors [3].

Furthermore, the study pointed that an eating problem, in

children over 2 years, resulted in underweight over the first 2 years;

eleven percent had weight loss compared with three percent of

children who were not diagnosed as having an eating trouble.

Accordingly, weight loss is more common in picky eaters and

excessive milk-drinking may be a cause of low appetite at regular

mealtimes. Currently, there are not enough research studies and

approved information about the impact of picky-eating behavior

on the nutritional and growth status of preschoolers. A study that

compared the weight, height, and weight-for-height percentiles of

thirty four children with picky-eating behavior and 136 healthy

controls concluded that seven of 34 children (20.6%) in the pickyeating

group and nine of 136 (6.6%) in the control group were

underweight; being underweight was found in fifteen children

(14.2%) younger than 3 years old and in one child (1.6%) older

than three years old [21]. The investigators found that children with

picky-eating habits are at an increased risk of being underweight,

particularly in those younger than 3 years old.

According to our data, weight and height of picky eaters were

significantly lower than non-picky eaters: In general, the weightfor-

age, height-for-age, and BMI-for-age percentiles of non-picky

eaters were above 50th, while picky’ eaters were under 50th. Also,

compared with non-picky eaters, z-score of weight-for-age, heightfor-

age, and BMI-for-age in picky eaters was 0.91, 0.73, and 0.44

SD lower, correspondingly (Table2). Furthermore, picky eaters

comprised significantly higher proportions of children who were

underweight, short, and with low BMI (<15 percentiles) compared to non-picky eaters. A negative impact of picky eating behaviors

on growth was found in pre-school and early school-age children.

However, in a study conducted in Saudi Arabia, 315 pre-school

children with eating problems as compared to one hundred health

control revealed that the main feeding problems detected were

picky eating in 85.5% of feeding problem with normal growth

group, these group children were still having normal growth

parameters, but they had significantly lower growth parameters

than healthy children [15].

Moreover, in a China study of nine hundred thirty-seven

recruited healthy children of 3-7 years old concluded the

prevalence of picky eating as reported by parents was fifty four

percent ; the weight for age z-score was significantly lower in picky

eaters compared to non-picky eaters [8]. Furthermore, dietary

consumption in preschoolers might be negatively influenced by

pickiness behavior. A randomized trial of Chinese preschoolers

(aged 2.5-5 years) based on validated dietary analysis software of

local database of recommended nutrient intakes concluded that

median daily energy intake was twenty five percent lower than the

age-appropriate intake in preschool picky eaters, and found that

preschool picky eaters with low weight-for-height index was at risk

for significant dietary and nutrient deficiencies [27]. In that study,

almost fifty percent of the picky eaters met the recommendation for

daily servings of fruit, and fewer in vegetables (14.7%) and dietary

products (6.3%), and grains and cereals (6.3%) [27]. Furthermore,

in Chinese study, preschoolers (ages 3-7 years) concluded that

picky eaters had lower intakes of protein, dietary fiber, vegetables,

fish, and cereals, compared with non-picky eaters [8].

Another study of Chinese young infants and toddlers (6

months-3 years) observed that lower intake of eggs and their food

cohort in picky eaters compared to non-picky eaters [9]. However, in

our study, the common dislike foods among preschool picky eaters

(ages 2-4 years) were meat, vegetables and fruit (37%, 39%, 22%)

respectively. Besides, a research study of four hundred twenty six

German children aged 8-12 years revealed that pickiness behavior

was linked to abnormal behavior for instance, anxiety, depression,

withdrawal and somatic complaints, as compared to normal

behavior in non-picky eaters [4]. The link between numerous

eating disorders (overeating, anorexia, or feeding difficulties)

and development has been reported in children and adolescents

(28-33), while the association between picky-eating habits and

development in preschool children has rarely been documented.

However, in our study, we found positive correlation between

picky-eating behaviors and low-quality general development in

preschoolers with unknown reason due to deficient evidence in

research and literature.

Besides, picky eaters tended to have a greater fear of unfamiliar

places as compared to non-picky preschoolers. A future longitudinal

study and further studies are required to illuminate the underlying

consequence relationship between picky eating and low-quality

of general development. Also, picky eaters tended to have lower

values of the performance in physical activities especially a lower

level of stair-climbing. In addition, picky preschoolers tended

to have higher risk of constipation and acute infectious illness

as compared to non-picky preschoolers. Likewise, Picky eaters

(aged 3-5 years) with growth faltering who were randomized to

receive 3-month oral nutritional supplementation had significantly

greater increases in weight and height than non-supplemented

controls and developed proportionally fewer upper respiratory

tract infections. In Filipino children, long-standing oral nutritional

supplementation helped promote nutritional adequacy and growth

who were at risk of nutritional deficiency. The findings showed that

long-term use of oral nutritional supplement enhanced food variety

and promoted sufficient intake of nutrients that were inadequate

in Filipino children’s diets without interfering the intake of normal

family meals [28].

Therefore, picky preschoolers had improvement in their growth

after consuming oral nutritional supplementation. Another interesting

randomized controlled trial of Chinese picky preschoolers

aged 3-6 years old and weight-for-height ≤25th percentile showed

higher significant changes in growth parameters and nutrient intake

in the group with a nutritional milk supplement than the group

with nutrition counseling alone. As comparison to the children with

nutrition counseling alone, increases in weight-for-age z-scores and

weight-for-height z-scores were significantly better at 3 months,

and increases of intakes in energy, protein, carbohydrate, docosahexaenoic

acid, arachidonic acid, calcium, phosphorous, iron, zinc,

and vitamins (A, C, D, E, B6) were significantly elevated at 2 months

and 4 months in the children with a nutritional milk supplement.

The power of this study included the population-based design in

preschool children and extensive questionnaire to assess picky eating

behavior, growth status, quality of development, level of physical

activity, and health status [29].

To reduce the selection bias, the participants enrolled were

healthy, with good economic state and no need for nutrition

support; the caregivers had sufficient knowledge and perception

in children’s diets, development, and physical activities. Moreover,

our study defined the picky eating by objective questionnaires and

scored the performance on each questionnaire items of development

and physical activity to demonstrate the difference of development

and physical activities between picky and non-picky eaters,

this to empower the scientific credibility. Our study has certain

limitations. The self-rating questionnaires only presented the point

of views from caregivers, over-/underestimation in reporting may

exist due to lack of objective behavioral observations on eating

behaviors, interaction, developments, and physical activities. lastly,

the inclusion of participants from two various places may limit the

generalization of the findings to the whole country [30].

Overall

Pickiness behaviors in preschoolers might have negative impacts and consequences on development quality, physical activity level, and general health status. Therefore, Parents and caregivers need to be well informed and taught about feeding strategies to enhance adequate food variety for their preschoolers and to increase the number of foods accepted by their toddlers and appropriate dietary interventions to develop sound feeding solutions to address pickyeating behaviors. Also, clinicians might play a vital role to guide and support parents and caregivers on the finest approaches to reach the best possible nutrition for their children who are picky eaters, and early diagnosis and clinical intervention of pickiness behavior among preschoolers might help to reduce or limit the negative impacts of such behavior on children’s growth and development.

Availability of Data and Materials

Data for research purposes are available upon request.

Consent for Publication

All participants gave and provided their written consent forms.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgement

We thank and acknowledge all children and their parents or caregivers for their time and efforts to take part in this research project.

Funding

This study was not funded by grants or other financial sponsors. The authors declare that they have no financial arrangement with a company whose product is discussed in the manuscript.

References

- Jacobi C, Schmitz G, Agras WS (2008) Is picky eating an eating disorder? Int J Eat Disord (2008) 41(7): 626-634.

- Galloway AT, Fiorito L, Lee Y, Birch LL (2005) Parental pressure, dietary patterns, and weight status among girls who are “picky eaters”. J Am Diet Assoc 105(4): 541-548.

- Wright CM, Parkinson KN, Shipton D, Drewett RF (2007) How do toddler eating problems relate to their eating behavior, food preferences, and growth? Pediatrics 120(4): e1069-1075.

- Jacobi C, Agras WS, Bryson S, Hammer LD (2003) Behavioral validation, precursors, and concomitants of picky eating in childhood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 42(1): 76-84.

- Nicholls D, Bryant Waugh R (2009) Eating disorders of infancy and childhood: definition, symptomatology, epidemiology, and comorbidity. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 18(1): 17-30.

- Mascola AJ, Bryson SW, Agras WS (2010) Picky eating during childhood: a longitudinal study to age 11 years. Eat Behav 11(4): 253-257.

- Carruth BR, Ziegler PJ, Gordon A, Barr SI (2004) Prevalence of picky eaters among infants and toddlers and their caregivers’ decisions about offering a new food. J Am Diet Assoc 104(1Suppl 1): s57-64.

- Xue Y, Zhao A, Cai L, Yang B, Szeto IM, et al. (2015) Growth and development in Chinese pre-schoolers with picky eating behaviour: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One (2015) 10(4): e0123664.

- Li Z, Van der Horst K, Edelson Fries LR, Yu K, You L, et al. (2017) Perceptions of food intake and weight status among parents of picky eating infants and toddlers in China: A cross-sectional study. Appetite 108: 456-463.

- Goh DY, Jacob A (2012) Perception of picky eating among children in Singapore and its impact on caregivers. A questionnaire survey. Asia Pacific Family Medicine 11(1): 5.

- Micali N, Simonoff E, Elberling H, Rask CU, Olsen EM, et al. (2011) Eating patterns in a population-based sample of children aged 5 to 7 years. Association with psychopathology and parentally perceived impairment. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics 32(8): 572-580.

- Shim JE, Kim J, Mathai RA (2011) Associations of infant feeding practices and picky eating behaviors of preschool children. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 111(9): 1363-1368.

- Chatoor I, Ammaniti M (2007) Classifying feeding disorders of infancy and early childhood. In Narrow WE, First MB, Sirovatka PJ, Regier DA, (Eds.)., Age and Gender Considerations in Psychiatric Diagnosis. A Research Agenda for DSM-IV. APA Publishing, Arlington, VA, pp. 227-242.

- Kerzner B (2009) Clinical investigation of feeding difficulties in young children: a practical approach. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 48(9): 960-965.

- Hegazi MA, Sehlo MG, Al Jasir A, El Deek BS (2015) Development and cognitive functions in Saudi pre-school children with feeding problems without underlying medical disorders. J Paediatr Child Health 51(9): 906-912.

- Steyn NP, Nel JH, Nantel G, Kennedy G, Labadarios D (2006) Food variety and dietary diversity scores in children. Are they good indicators of dietary adequacy? Public Health Nutrition 9 (5): 644-650.

- Woolston (1983) Eating disorders in infancy and early childhood. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry 22(2): 114-121.

- Kotler LA, Cohen P, Davies M, Pine DS, Walsh BT (2001) Walsh Longitudinal relationships between childhood, adolescent, and adult eating disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 40(12): 1434-1440.

- McDermott BM, Mamun AA, Najman JM, Williams GM, O'Callaghan MJ, et al. (2010) Longitudinal correlates of the persistence of irregular eating from age 5 to 14 years. Acta Paediatrica 99(1): 68-71.

- Nicklaus S, Boggio V, Chabanet C, Issanchou S (2005) A prospective study of food variety seeking in childhood, adolescence and early adult life. Appetite 44(3): 289-297.

- Dubois L, Farmer AP, Girard M, Peterson K (2007) Preschool children's eating behaviours are related to dietary adequacy and body weight. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 61(7): 846-855.

- D Benton (2010) The influence of dietary status on the cognitive performance of children. Molecular Nutrition and Food Research 54(4): 457-470.

- Mc Afee AJ, Mulhern MS, Mc Sorley EM, Wallace JM, Bonham MP, et al. (2012) Intakes and adequacy of potentially important nutrients for cognitive development among 5-year-old children in the Seychelles Child Development and Nutrition Study. Public Health Nutrition 15(9): 1670-1677.

- (2006) World Health Organization, WHO Child Growth Standards: Methods and development. WHO pp. 312.

- Jacobi C, Schmitz G, Agras WS (2008) Is picky eating an eating disorder? Int J Eat Disord (2008) 41(7): 626-634.

- AJ Mascola, SW Bryson, WS Agras (2010) Picky eating during childhood. A longitudinal study to age 11 years. Eating Behaviors 11(4): 253-257.

- Dovey TM, Staples PA, Gibson EL, Halford JC (2008) Food neophobia and ‘picky/fussy’ eating in children. A review. Appetite 50(2-3): 181-193.

- Galloway AT, Fiorito L, Lee Y, Birch LL (2005) Parental pressure, dietary patterns, and weight status among girls who are “picky eaters”. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 105(4): 541-548.

- Li D, Jin Y, Vandenberg SG, Zhu YM, Tang CH (1990) Report on Shanghai norms for the Chinese translation of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Revised. Psychological Reports 67(2): 531-541.

- Gonçalves Jde A, Moreira EA, Trindade EB, Fiates GM (2013) Eating disorders in childhood and adolescence. Revista Paulista de Pediatria 31(1): 96-103.

Research Article

Research Article