Abstract

It was envisaged to observe the effect of Dietary Habit on behaviour pattern of adolescent boys. In the present study 150 adolescent boys, in the age group of 12- 17 years, were selected though random sampling. All the subjects were divided into two groups on the basis of vegetarian and non-vegetarian dietary habits, each group consisting of 75 adolescent boys. Behavioural dimensions like problem solving ability and Adjustment were assessed by using L.N. Dubey’s Problem-Solving Ability Test, Ragini and Dubey’s Adolescent Adjustment Scale. The independent sample ‘t’ test was used for statistical evaluation of the effect of dietary habit on behavioural pattern. A significant change was noticed in problem solving ability at 0.01 level and rest another psychological parameter were not found significantly changed. But the mean value showed that vegetarian intake pattern does positively influence the adjustment ability.

Keywords: Vegetarian & Non-Vegetarian Diet; Problem Solving Ability and Adjustment and Adolescent

Introduction

Adolescence is considered as a nutritionally critical period

of life for several reasons. Firstly, manifold increase in physical

growth and development put greater pressure on the need for

nutrients. Secondly, adolescence can be the second opportunity

to catch up with growth, if nutrient intake is appropriate. Thirdly,

psychological changes and development of their own personality

exert impact on their dietary habits during the phase when they

are very prone to suggestions. All these changes create special

requirements for additional nutrition, thus making nutrition

a significant determinant of their health. Inadequate nutrition

also affects adolescent’s current health and put them at high risk

of chronic diseases as well, particularly if combined with other

adverse lifestyle behaviours [1]. Adolescents need good mental

health to experience normal emotional and mental development,

to develop their potential, to have fulfilling relationship with other

people and to deal with the challenges of everyday life.

The social approach to mental health focuses primarily on

behaviour and performance in various social roles. These consist

of estimate of the extent to which individuals follow and respond

to a community’s normative prescription and expectations of

appropriate behaviour in roles related to occupation and work,

social participation and family relations [2]. Behaviour is the study

of human actions by analyzing stimulus and response. The delicate

chemical balance to the brain is somewhat protected by blood brain

barrier, which restricts entry of certain chemicals to the brain via

blood. Nevertheless, the brain is highly susceptible to changes in

body chemistry resulting from nutrient intake and deficiency. The

brain receives, stores, and integrates sensory information and

intimates as well as controls motor responses. These functions

correspond to mental activities and form the basis of behaviour.

Thus, there appears a direct connection between nutrition, brain

function and behaviour.

Behaviour in its broad sense includes all types of human

activities like walking and speaking, cognitive activities such as

perceiving, remembering, thinking or reasoning and emotional

activities like feeling happy, sad, angry or afraid [3]. A good diet

is necessary in order to perform well but this is usually thought

of in physical terms only. The type and quality of food affects

the physical and mental conditions of the individual. Thus, the

individual who does not take a proper diet and who does not have

a proper understanding of the principles of eating gradually begins

to harm himself, both physically and mentally. He begins to feel the

ill effects of wrong eating pattern on his appearance, behaviour,

thought and also in action. It is estimated that the human body

requires somewhat 40 to 50 nutrients in all to function properly

[4]. There are many other substances that exist in food that may be

useful to or necessary for the human body, but little is known about

them. Adolescents have the highest prevalence of “Unsatisfactory”

nutritional status among all age groups.

Reflecting a commonly held belief a recent long-term study

has confirmed that adolescent behaviour and mental health may

have deteriorated significantly and measurably over the past 25

years [5]. A child who suffers from nutrient deficiencies exhibits

physical and behavioural symptoms. Deficiencies of protein

energy, vitamin A, iron and zinc plague children the world over.

Iron deficiency remains common in children and adolescents

despite iron fortification of foods and other programs to combat

this deficiency. A lack of iron not only causes an energy crisis but

also directly affects behaviour, mood, attention span, and learning

ability [6]. Diet can affect cognitive ability and behaviour in children

and adolescents. Nutrient composition and meal pattern can exert

immediate or long term, beneficial or adverse effects. Beneficial

effects mainly result from the correction of poor nutritional status.

One aspect of diet that has elicited much research on young people

is the intake/omission of breakfast. This has obvious relevance to

school performance.

While effects are inconsistent in well-nourished children,

breakfast omission deteriorates mental performance in malnourished

children. The literature suggest that good regular dietary

habits are the best way to ensure optional mental and behavioural

performance at all times. In contrast, children and adolescents with

poor nutritional status are exposed to alterations in mental and/

or behavioural functions that can be corrected, to a certain extent,

by dietary measures [7]. Thus, it seems that there is a direct link

between nutrition, brain function and behaviour. Nutrient composition

and meal pattern can exert immediate or long term beneficial

or adverse effects. Literature suggest that good regular dietary

habits are the best way to ensure optimum mental and behavioural

performance at all times. Therefore, it was proposed to study the inter-

relationship between the vegetarian & non- vegetarian dietary

habits and their various behavioural manifestations, like problem

solving ability and adjustment ability of adolescents.

Methodology

Sample Selection

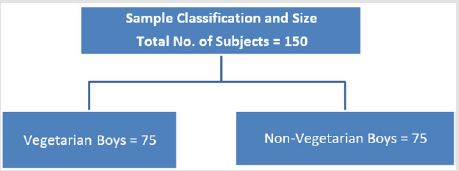

Total 150 adolescent boys in the age group of 12-17 years were, selected through random sampling. They were from 8th, 9th, 10th and 11th standard of their study. Further, all subjects were pooled and then divided in to two groups on the basis of vegetarian and nonvegetarian dietary habits. Each group consists of 75 adolescent boys (Figure 1). The study was preceded with the selection of adolescent boys aged 12-17 years of age through deliberate stratified random sampling method from Mayo Boys College, Ajmer.

Tools and Techniques

In the present study, dietary habits (Vegetarian and Non-

Vegetarian Diet) of adolescents were the independent variables,

whereas behavioural dimensions like problem solving ability and

adjustment ability were taken as dependent variables. Collection of

data was done by performing following psychological tests on both

vegetarian and non-vegetarian adolescent boys:

1) L.N. Dubey’s problem-solving ability test

2) Ragini Dubey’s adolescent adjustment scale

Procedure for Data Collection

Once the object and propose of the research was finalized the researcher started planning the process of collection of data by considering availability, approachability etc. With this view Mayo Boys College, Ajmer principal responded and finally granted permission. Once the school principal agreed in principle that the time and dates suggested by the researcher does not interfere with the conduct of school curriculum and calendar, liaison visits were done with the above school, where principal were given necessary presentation, logistic support expected, suitable dates that would not interfere with any school activity. Finally, the date was fixed and confirmed for the collection of data. On the appointed date and time actual tests were performed and scores were obtained for each test separately on every participant. After that the data were tabulated for statistical analysis and the independent sample ‘t’ test was used for statistical evaluation of the effect of dietary habit.

Results

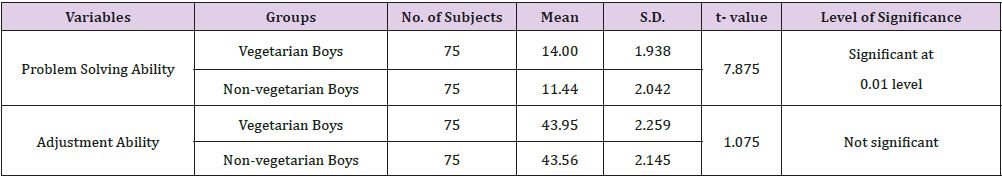

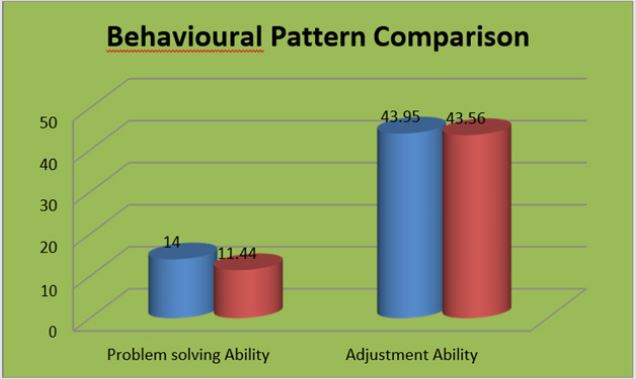

This component contains the analyzed data comprising effect of dietary habits on problem solving ability and adjustment ability of vegetarian and non-vegetarian adolescent boys along with their interpretation. The mean score of problem-solving ability in vegetarian boys was observed to be 10.72 and the same in nonvegetarian boys was 8.61 with the standard deviation of ±3.17 and ±3.45 for the respective means. The difference between two mean values was statistically significant at p<0.01. The significant difference between the two means shows that dietary habits do influence the problem-solving abilities of adolescent boys (Table 1) (Figure 2). Contrary to that the mean scores of adjustment ability in vegetarian boys were recorded to be 43.95±2.259. Whereas the mean scores of abilities in non-vegetarian boys were calculated to be 43.56±2.145 (Table 1) (Figure 2). The differences, whatsoever, in inter variable mean scores were not significant in the variable of adjustment. One of the reasons for such insignificant differences was the higher values of standard deviation. This observation exhibits that the dietary habits do not influence much in case of adjustment ability. The scores of both vegetarian and non-vegetarian boys show that in spite of insignificant difference the adjustment level in vegetarian boys was at higher side in comparison to non-vegetarian counter parts.

Discussion

The difference in mean values of two variables- problem

solving ability and adjustment ability, with statistical significance,

suggests that the vegetarian boys have better problem-solving

ability as compared to non-vegetarian. There are evidences that

vegetarianism affects not only mood, but also cognitive ability [8].

In a study Sigman et al. [9] found that children who had vegetarian

diet and were better nourished had higher composite score on

verbal comprehension test and the Raven’s matrices. A series of

studies, reported by Schoenthaler et al. [10], have widely been

quoted. These studies examined the effect of dietary patterns on

large number of non-vegetarians. The author claimed decrement

in problem solving ability, aggressive and hyperactive behaviour

which are contrary to our findings. Paul et al. [11] examined 6000

vegetarians and 5000 non-vegetarians in the United Kingdom using

cross sectional analysis. They found that physical and mental health

of vegetarians was comparatively better than non-vegetarians.

Traditionally, research into vegetarianism focused mainly

on potential nutritional deficiencies, but in recent years, the

pendulum has swung the other way, and studies are confirming

the health benefits of meat free eating. Nowadays, plant-based

eating is recognized as not only nutritionally sufficient but also

as a way to reduce the risk for many chronic illnesses [12]. The

American Dietetic Association weighed in with a position paper,

concluding that “appropriately planned vegetarian diets are

healthful, nationally adequate, and may provide health benefits in the prevention and treatment of certain diseases” (American

Dietetic Association Report, 2009). But there are still not enough

data available to explain exactly how a vegetarian diet influences

long term health. Vegetarians tend to consume less saturated fat

and cholesterol and more vitamins C and E, dietary fiber, folic

acid, potassium, magnesium and selected phytochemicals such as

cartenoids and flavonoids. As a result, they are likely to have lower

total and LDL (bad) cholesteral, lower blood pressure, and lower

body mass index (BMI), all of which are the indicators of longevity

and a reduced risk for many chronic diseases [13].

There are two popularly held explanations for the primary form of depression and frustration which is brought in a neuro-chemical imbalance. One attributes the condition to a deficiency of serotonin, the other to inadequate norepinephrine. It was assumed that by increasing the level of these neurotransmitters thought to be due to increased dietary intake of their precursors mainly through vegetarian diet. Although the concentration of brain cell norepinephrine and dopamine do rise, concomitant with increased precursors (tyrosine) intake, the effect of tyrosine loading on behaviour alteration and mental capacities remains controversial [14]. It is not surprising that since the intake of large amount of acetylcholine precursors increases the neuronal concentration and release of the neurotransmitter and that leads to change in mental activities. There is a great deal of interest in the possible enhancement of cognitive ability, problem solving ability and memory through dietary precursor loading mainly by vegetarian diet. On the same line our findings also indicate that vegetarian diet does influence positively to problem solving ability of adolescent boys.

Similarly impact of dietary habits on adjustment ability amongst adolescent boys seems to be slightly tilted towards vegetarians. This conclusion is arrived by simple observation and comparison of the mean scores obtained for vegetarian and non-vegetarian adolescent boys, which indicates that vegetarian adolescent boys have better adjustment ability than non- vegetarian boys. It gives an idea that non-vegetarian diet does influence the interpersonal relationship negative amongst adolescents’ boys. This may possibly because of high intake of the precursors of excitatory neurotransmitters through non vegetarian diet which is a well-established fact [15]. Prinz et al. [16] examined the diets of hyperactive and aggressive children and reported that most of them liked to have non-vegetarian food items. Rodriguej et al. [17] evaluated the indicators of anxiety and depression in subjects with different kinds of diets. They observed significant differences in anxiety and depression levels between two groups. More anxiety, frustration and depression were reported in non-vegetarians. In addition, diet analysis found more nutritional antioxidant levels in the vegetarian group in comparison with non- vegetarian group.

Our results are in the conformity of these findings. With physiological point of view, serotonin is an important neurotransmitter in the brain particularly in the frontal lobe. Low serotonin in the brain is said to be important factor in treating depression. The body needs certain raw materials to make serotonin. One of these materials is the amino acids, of which quality comes from vegetarian diet. So, eating vegetarian food items optimizes serotonin production [18]. Herrick et al. [15] reported that non-vegetarian diet terminates the state of frustration and depression. Herrick also stated that non-vegetarian food substances, caffeine, nicotine, food coloring and preservatives over stimulate secretary glands, interfere with the processing of nutrients, weaken immune system and cause several other harmful effects which contribute to anxiety, depression, frustration and lack of adjustment capacity. Such findings support the trends of the findings of present study. Geary et al. [19-21] observed that food can affect our mental capacity and what we choose to put into our mouth can influence our state of mind. Our findings indicate when we compare the problem-solving ability of vegetarian and non-vegetarian adolescents, vegetarian were at strong side, probably because of higher level of mental state. It may be inferred from the results that behavioural dimensions like problem solving ability and adjustment ability in adolescent boys is positively influenced more in vegetarian boys than in non-vegetarian boys and thus it may be concluded that vegetarian diet promotes the problem- solving ability and adjustment ability in adolescent boys.

References

- Bamber DJ, Stokes CS, Stephen AM (2007) The Role of Diet in the Prevention and Management of Adolescent Depression. Nut Bulletin 32(1): 90-99.

- Gupta P, Ghai OP (2007) Textbook of Prevention and Social Medicine. 2nd (Edi.), New Delhi: C.B.S. Publishers and Distributors.

- Donovan UM, Gibson RS (1995) Iron and Zinc Status of Young Women Aged 14 to 19 Years Consuming Vegetarian and Omnivorous Diets. Journal of Am Coll Nutr 14(5): 463-472.

- Larsen CS (2000) Dietary Recon and Nutritional Assessment of Past Peoples: The Bio- Anthropological Record. The Cambridge word history of food. The Cambridge University Press, UK p. 1.

- Brewerton T, Heffernan M, Rosenthal NC (1986) Psyciatric Aspects of the Relationship between Eating and Mood. Nutr Rev 44(Suppl 3): 78-88.

- Siefert K, Heflin CM, Cororan ME, Williams DR (2001) Food Insufficiency and The Physical and Mental Health of low-income Women. Journal of Women and Health 32(1-2): 159-177.

- Bellisle F (2004) Effects of Diet on Behaviour and Cognition in Children. British Journal of Nutr 92(Suppl 2): 227-232.

- Rogers PJ (2001) A Healthy Body, A Healthy Mind: Long Term Impact of Diet on Mood and Cognitive Function. The Proc of Nutr Soc 60(1): 135-143.

- Sigman M, Meumann C, Jansen AA, Bwibo N (1989) Cognitive Abilities of Kenyan Children in Relation to Nutrition, Family Characterisitics and Education. Child Dev 60(6): 1463-1474.

- Schoenthaler SJ (1983) Diet and Delenquency: A Multi State Replication Int. Journal of Biosocial Research 5: 70-78.

- Paul NA, Margaret T, Jim IM, Timothy J (1999) The Oxford Vegetarian Study: An Overview. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 70(3): 525-531.

- Greenberg JS (2007) Comprehensive Stress Management, (12th)., McGraw-Hill, 2011, New York, USA, p. 85.

- (2014) Food and Nutrition Information Center, Vegetarian Nutrition from www.nal. usda.gov/fnic/etext/000058.html

- Fernstrom JD, Faller DV (1978) Neutral Amino Acids in the Brain: Changes in Response to Food Ingestion. Journal of Neuro Chem 30(6): 1531-1538.

- Herrick K, Phillips DI, Haselden S, Shiell AW, Campbell Brown M, et al. (2003) Maternal Consumption of High Meat, Low Carbohydrate Diet in Late Pregnancy: Relation to Adult Cortisol Concentrations in the Offspring. Journal of Clin Endocrinol Metab 88(8): 3554-3560.

- Peinz RJ, Roberts WA, Hantman E (1980) Dietary Correlates of Hyperactive Behaviour in Children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 48(6): 760-69.

- Rodriguez J, Rodriguez JR, Gonzalez MJ (1998) Indicators of Anxiety and Depression in Subjects with Different Kinds of Diet: Vegetarians and Omnivores. Bol Asoc Med PR 90(4-6): 58-68.

- Nedley N (2005) Depression and The Nutrient Connection. Depression the way out. Fredericksburg, USA.

- Geary A (2001) The Food and Mood Handbook. London: Thorsons Com, UK.

- Kaye WH, Klump GK, Strober M (2000) Anorexia and Bulimia Nervosa. Annual Review of Medicine 51: 299-313.

- Orlich MJ, Sigh PN, Sabate J, Karen Jaceldo Siegl, Jing Fan, et al. (2013) Vegetarian Dietary Patterns and Mortality in Adventist Health Study? JAMA Internal Medicine 173(13): 1230-1238.

Research Article

Research Article